Wallace Tours Again

The name David Foster Wallace calls many words and labels to mind: wit, footnotes, tragedy; novelist, observer, teacher, prophet. The author, who took his own life in 2008 at the age of 46, is a tough topic to tackle, and that’s to say nothing of his devout fan base. In The End of the Tour, however, director James Pondsoldt (Smashed, The Spectacular Now) goes beyond the myth of the troubled literary genius and shows Wallace as a human and a friend.

Ponsoldt’s fourth feature film, The End of The Tour, follows author David Foster Wallace (Jason Segel) as Rolling Stone reporter David Lipsky (Jesse Eisenberg) interviews him during the final leg of the book tour for Wallace’s magnum opus Infinite Jest. The five days that Wallace and Lipsky spent together in 1996 blend into an extended conversation—sometimes flowing freely, other times painfully strained—and in watching it you feel as though you’ve entered a snowy, small town time warp. What begins as an interview rooted in fandom develops into mutual admiration between two 30-something writers, as they converse about shyness, muse over Alanis Morissette (of whom Wallace has a poster on his wall), discuss the moniker “genius,” and to Wallace’s chagrin, his now signature bandana.

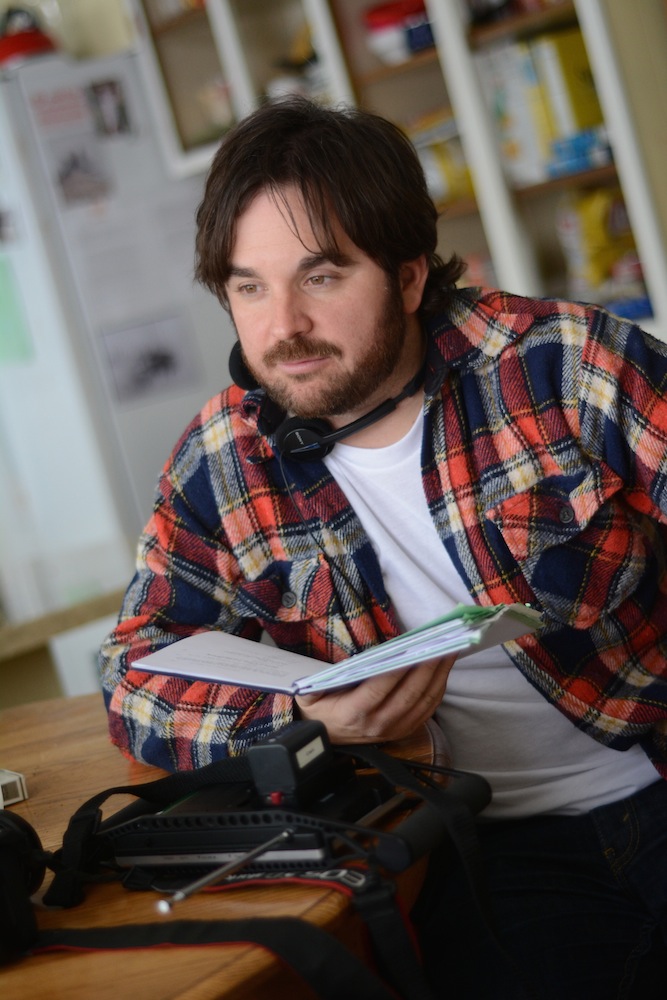

Ponsoldt called us from Los Angeles, California a few weeks after we met him at BAMcinemaFest’s premiere of The End of the Tour.

HALEY WEISS: When we spoke at BAMcinemaFest you said that Infinite Jest was the “defining relationship of your freshmen year in college.” What was it about reading that novel at that time that was so impactful?

JAMES PONSOLDT: I think it was that I was 18 and away from home for the first time. I knew that I wanted to write, to tell stories, and I was already pretty sure I wanted to make movies. My mother had written short stories when I was a kid, my grandfather had painted book covers for a living, and my father had written poems. I grew up in a house with a lot of books and we revered great writers. I had also been interviewing bands for an alt weekly and kept along that path. So the idea of a writer’s life, and important books—the books that were defining my generation—were things that were really exciting. I wasn’t embittered and cynical. And then this book comes along, and it’s over 1,000 pages long! It was just so audacious. You can imagine a community of young, too-smart-for-their-own-good kids, encountering this book—English majors to boot, which is what I was—that book was a challenge to all of us. It was a challenge to try to read it, and a challenge in our own lives to create something that was so revealing, so personal, and so audacious.

WEISS: How much of the dialog in the film is taken directly from David Lipsky’s interview recordings?

PONSOLDT: Donald Margulies didn’t listen to the recordings [when he wrote the screenplay], he only used David Lipsky’s book [Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, in which Lipsky recounts his time with Wallace] as a resource, and he spoke to David Lipsky. David Lipsky later did give the tapes to me, which I listened to, and I gave to the actors. I’m guessing that probably 75 or 80 percent of the dialog came from his book. Obviously, this isn’t a documentary, and Donald Margulies has a background as a visual artist, a collage artist, so that’s a lot of what he was doing [in writing the screenplay]. If one reads Lipsky’s book closely they will notice that there are conversations that might occur at the end of the book but earlier in the film and vice versa. It’s going for the very subjective, emotional truth of what David Lipsky experienced for the few days that he was with Wallace. It’s Lipsky’s story about how he was affected by Wallace, and he’s the one who got the chance to tell that story.

WEISS: So you’d say you approached the film as an adaptation of the book rather than as a biopic of Wallace?

PONSOLDT: Oh, I hate biopics. We all hate biopics. [both laugh] We hate them because they’re usually cheesy and shallow, right? I don’t think a long life well lived, a messy life where people took chances, can really be explained away in 105 minutes. The fact that someone is stung by a bee, or breaks their leg when they’re in first grade, doesn’t explain why their marriage falls apart 30 years later, or why they win a prize, or why they do some great or terrible thing. Lives are more complicated than that. Trying to draw those easy conclusions, that kind of pop psychology, is inherently reductive and feels dumbed down. That doesn’t necessarily appeal to me. I like the idea of trying to go deep in a much shorter amount of time.

WEISS: What was it like to shoot in Grand Rapids, Michigan during the winter? Other than freezing cold.

PONSOLDT: It was great! [laughs] The bulk of the actual story takes place in Illinois, as well as in Minneapolis and New York, and we needed a place that could feel like Bloomington-Normal, where Wallace lived and where [Illinois State University] is. It was a totally alien area to me… The weather was super intense, it was during a polar vortex, but honestly, it was romantic. That sounds so cheesy, but I had this feeling that certainly for Lipsky, coming from New York City, there was something very different than his experience living in Manhattan of being in the Midwest with the strip malls, Walmarts, 7-Elevens, etcetera. [Those are] things that I relate to very much because I’m from a part of the country that has that. I’m from Georgia, so for me there’s real emotion and nostalgia in a place like that. Grand Rapids had that, but with all of that snow.

I lived in New York for a while, and my whole family is from right outside of New York. My experience of that time of year—this was in March—by February, March when I lived in New York I was just ready for the winter to end. It was slushy, and at rush hour trying to get on the train I’d step in a puddle, and then my ankle was wet… It’s kind of miserable and gray, or that’s how I would feel, whereas in Grand Rapids, it was just so white. There was something magical and hermetic about it that we wanted to capture in the film. There was something really emotionally pure about that weather. Which is very different than a lot of films, especially American independent films that take place in the winter and use it as a cheap or easy metaphor for existential despair or nihilism or something. That was not our take on it. These guys loved spending time together, and their time together was really special, and I think Lipsky wished that it could have gone on longer. That was certainly what I wanted the audience to feel.

WEISS: Something that struck me about the film was watching a portrayal of a literary icon and realizing just how contemporary his concerns still seem. He was addicted to television. He was concerned about how screen time would change him, and questioning what it means to be American. He even ate junk food. There’s something there that breaks through the cult of personality of the genius writer.

PONSOLDT: I think that’s part of what is compelling and addictive about Wallace’s writing, both with Infinite Jest and all of the articles he wrote like “Shipping Out,” the cruise ship essay [which Wallace wrote for Harper’s Bazaar in 1996] that was later included in A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. People described his essays as reading verbal cocaine. You had the sense of someone being able to articulate the way our interior voice speaks, and the way we feel in an increasingly ADD culture where there are so many things are vying for our attention. [Now] we have these tiny screens [that offer] so much opportunity for entertainment and consumption. He was attempting to create the quality of that psychological experience in his writing, and to be funny, and relatable, and be not pretentious about it, but to be ambitious. All of these things were so hard, it was a tightrope walk, and he pulled it off. I think he was thinking about the world he was living in then, and what was right around the corner. A lot of what he wrote about and anticipated has and is coming to pass. In many ways there was something very prescient in the way that he wrote. Now, almost seven years after he passed away, new readers are discovering him and finding a real kindred spirit that deeply moves them.

WEISS: It’s difficult not to acknowledge that Wallace committed suicide in 2008. How did knowing that influence your treatment of him as a character?

PONSOLDT: I think it was really important to not let it influence me too much. For people who aren’t as familiar with Wallace or his writing, they know that he wrote a big challenging book, and that he died tragically. But that happened 12 years after our movie takes place, and it doesn’t at all affect his time with Lipsky. When someone has died in a tragic way, sometimes people want to turn them into a martyr or a saint. But we really wanted to depict Wallace with honesty and clarity, in the way that David Lipsky experienced him. David Lipsky who was a stranger to him. Wallace was in the presence of a stranger and a journalist, and both of those things are really important factors in the time that they spent together. We didn’t want to bowdlerize anything or sensationalize anything. Any tawdry details of Wallace’s life that happened outside of this [time] did not interest us and that’s not the movie I would ever want to make or would make.

WEISS: I think to focus on Wallace’s death would also fetishize the image of the struggling, depressed writer and would take away from depicting [Lipsky and Wallace’s] relationship.

PONSOLDT: I find movies about “tortured artists” that deal with suicide, or addiction, and romanticize it in any way, to be really toxic narratives. I hate them, personally. Having had plenty of friends who have struggled with addiction and mental illness and killed themselves, that’s a narrative I don’t want to put into the world. Part of what appealed to me about this specific moment in David Foster Wallace’s life was that he had worked really hard for something, did it well, and the world affirmed it. He was experiencing the success of that, and he had complicated feelings toward it, but he was also teaching, and teaching well. He was a great teacher, he was managing his mental health, and he was sober. This was a good time in his life. You can see [that] in footage of him from the interviews at that time, like the Charlie Rose interview from 1997, which was a year after our movie takes place. You see him in the presence of an interviewer, which is what our movie is about. You see how charming and funny and seductive [Wallace] could be. You get it; he was radiant. The people in my life who have dealt with depression are complicated but they can be the most radiant, joyful, and funny people you would ever hope to meet. I have no interest in depicting someone at their worst moments.

THE END OF THE TOUR COMES OUT FRIDAY, JULY 31.