The Memory Machine

When it comes to virtual reality, there are no codes and expectations; there is no tradition that separates audience and action. “Everybody thinks that this is going to be an augmented 3-D film,” says Canadian musician Patrick Watson. “That’s the biggest thing that you can’t explain to people before they try it,” he continues. “It’s not about 3-D—it’s not, ‘It’s going to be a little more exciting because it’s going to come close to my nose.’ I don’t think people really understand that.”

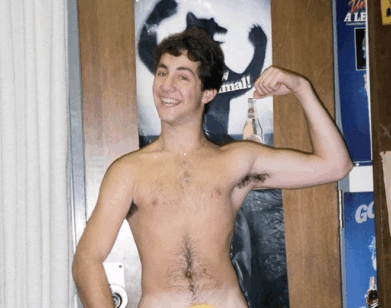

Watson is the subject a new short by French Canadian directing duo Félix Lajeunesse and Paul Raphaël. Titled Strangers and made in collaboration with directors Chris Lavis and Maciek Szczerbowski, Watson’s collaboration with Félix and Paul takes individual viewers into the musician’s Montreal studio as he plays the piano. Using a technology called the Oculus Rift, Lajeunesse and Raphaël change a scene into an environment. The viewer can watch Watson play or inspect the clutter in the room—Watson’s girlfriend’s first reaction to seeing the piece was to search for her keys. “You’re no longer a spectator; you’re a witness,” explains Lajeunesse. “When someone looks at you—at the camera—unlike cinema, it makes you feel uncomfortable.”

“It’s about as different as when cinema was invented and the train came out of the screen and people fell down in their chairs,” adds Watson.

Strangers is currently screening at Sundance as part of the Festival’s ninth New Frontier program. Lajeunesse and Raphäel have created two other shorts showing at the festival: a companion piece to the Reese Witherspoon film Wild, WILD—The Experience, and Herders, which explores the dying lifestyle of a group of Mongolian yak herders.

Here, Watson, Lajeunesse, Raphäel, and Interview editor Emma Brown discuss the purpose and future of the emerging art form of virtual reality.

PATRICK WATSON: I thought it could be fun to talk about the difference between virtual reality and cinema—all the discussions we had about how it’s a different way of telling a story.

FÉLIX LAJEUNESSE: Yeah, it’s fundamentally different. The more we do projects in virtual reality, the more we become radical about that difference. One of the main differences is that in VR, the viewer is part of the scene; in cinema, it’s not the case. The viewer is more of an abstraction. As a filmmaker working in VR, you really need to take this into consideration. It’s easy to try to retrofit the language of cinema into VR, to think that this is the proper way to tell the story.

WATSON: I remember we talked to Maciek and Chris about how it’s almost like a memory machine; it feels more like you’re living a memory than you’re watching a movie.

LAJEUNESSE: I think that you’re more vulnerable, too. Cinema is kind of far from you—you’re protected by that screen. In virtual reality that barrier, that separation, is gone and you become more vulnerable as a viewer. You become more present. Even if you go into VR with a mindset that you’re not going to like it and you’re not going to believe it’s reality, there’s a portion of your brain that will still kind of surrender to that alternate reality. There’s a portion of your mind that you can’t really control that will think that it’s part of this new space. I really think that it becomes an extremely emotional medium in that sense. It speaks to the senses and it speaks to something that is very deep inside the human mind. It triggers emotions in a very vivid way that I think cinema can’t really do.

WATSON: I think it’s more the medium of a documentary maker, because you have to make it look so real that your brain never second guesses itself—that you get lost there. A documentary-based filmmaker will, I think, excel more in this than someone who works in fiction and who’s used to creating a complete universe that’s isolated. For me, it’s a documentary machine. Fictions will be interesting much later, but, just like in film, the first half of the creations that will really profoundly move people will be in the documentary, very raw state. I feel making your own personal films on the VR will be the most interesting use of it. Looking at yourself from a different point of view is probably the strength of this machine.

LAJEUNESSE: It’s funny that you mention the notion of a memory machine, because it is a bit like encapsulating a moment of time and space—especially when you capture reality as we did with you when we did Strangers. It’s a bit as if you’re able to record a moment that can be preserved for the future. When we look at Strangers, every single time it gives me the feeling that I’m being sent back in time. There’s a change of seasons; if I’m watching the piece in the summer then I am back in Montreal during the winter months. It becomes very sensitive.

WATSON: Imagine something like [the documentary] Don’t Look Back with Bob Dylan. Imagine if that was recorded with VR and you sat backstage with Bob Dylan while they’re making all those jokes and they’re talking to people—actually looking around and looking at people look at Bob Dylan and how Bob Dylan moves and being a part of a moment like that. That’s why I think documentary will always be stronger. Imagine if my kid 20 years from now puts on the VR and sits in my studio when I’m a young man playing music, it would be so weird for him. It’s such a wild way of accessing a moment. There’s no art that offers such a weird experience.

LAJEUNESSE: There’s also a notion of human empathy. You don’t have to explain much with VR; if you have the viewer experience the presence of that human being, and you feel the presence of that human being, your body and your mind react to the presence. Let’s say we take a traditional film: the acting will need to be good, the writing will need to be good up to a point where you care for that character that’s on the screen. With virtual reality, the simple fact of having someone coming close to you makes you react as if that’s a real person. You care about the person in a very different way. For example, in Strangers there’s so many people that told us that the feel guilty looking away from you because you’re playing the piano.

WATSON: [laughs]

LAJEUNESSE: Patrick, I heard that so many times. People would be very static looking at you and we’re thinking, “Hey man, this is a whole environment, they should be looking around.” But people would say, “I didn’t feel like looking around. I felt like it would have been a bit impolite because he was playing music to me.” People react in a very visceral way to the presence of humans in VR, and people also talk about feeling empathy—that’s true for all of the pieces we’ve been viewing so far including Strangers. People care for the characters.

EMMA BROWN: I’m curious as to how it works with something like WILD, which is a fictional piece.

LAJEUNESSE: WILD is one of the pieces we’re going to show at Sundance. Patrick, I don’t think you’ve seen it.

WATSON: No.

LAJEUNESSE: It’s the first fiction piece we shot with Reese Witherspoon and Laura Dern. It’s a companion piece to the Jean-Marc Vallée film. In the case of WILD, we have to tell a story—there had to be a narrative dimension to the piece. But at the same time, we wanted to do it in a way that wouldn’t hinder the nature of the emotional experience. We went for the feeling of loneliness. In the actual film, there is a real sense of isolation and loneliness from the main character. We tried to recreate an experience in which the viewer would experience that but in a very direct way and without necessarily relying on association to a character. I believe that we managed to do it. The virtual reality piece WILD is very different from the film Wild. It’s inspired by the same story, by the same characters.

WATSON: But if you’re beside an actor that’s really famous, the first thing you’re going to do is just stare at the star that’s sitting beside you more than letting them be a character. I think that’s, for me, where the machine wouldn’t work if you’re using major actors. You’d be like, “Oh my god, I’m standing beside Reese Witherspoon!” And you’d be staring at her and you’d feel really impressed. I can’t believe that anyone would give into a famous actor. Isn’t it mostly people going “Holy shit, I’m sitting beside Reese Witherspoon?”

LAJEUNESSE: Well, some people have said that. But I’ll tell you the way we thought about this: when it begins, the viewer is alone in the forest. It’s a very quiet forest environment, and you just get the sense of nature. Then suddenly you hear a voiceover of Reese’s voice—the voice is very close and very intimate to you; it’s almost as if she was speaking inside your own mind. There’s this kind of connection of consciousness between you and her before you even get to see her. It sets the tone in a way that it makes the experience go into something more poetic.

PAUL RAPHAËL: The idea is to put the viewer in a mindset that’s closer to the dream state. In the real world, if you were sitting in the woods and Reese Witherspoon sat next to you and started playing a character, there’s just no way you would believe her. The way we set it up is that you kind of sink into this world and you lose your bearings a little bit. When you see Reese Witherspoon, of course you recognize her, but it’s a bit like in a dream you could be with a friend, and they’re not your friend—they’re someone else. It blurs that line a little bit.

WATSON: I’d have to try it. Because I know how intimidating the space is, so I think I’d be pretty intimidated by Reese Witherspoon hanging out with her in the forest.

RAPHAËL: Definitely it’s a big challenge. We took our first steps exploring fiction with WILD.

WATSON: Are you guys happy with it?

RAPHAËL: Yeah, definitely. Especially considering weeks earlier we were not sure that it was even possible at all. Like you were saying, it’s very far from a reproduction of a real event, so there’s this whole language to develop to alter the state of mind of the viewer. I think in the long term, there’s going to be a lot of work to be done.

WATSON: Why not take one of those rigs and put it on the front line of a war that we’re always so far from and we’re so blasé about? Those kinds of things would blow my mind—sitting on the front line of a war and feeling the sound and how scary it is. You could change people dramatically by changing how they experience all these things we see on the news that we feel so disconnected from.

LAJEUNESSE: That’s a great idea. There’s a case to be made also for connecting to realities that are totally foreign to us in a more subtle realm. For example, the piece that we did in Mongolia that we’re showing at Sundance, Herders, is a series of experiences with a family of Mongolian yak herders. When we went there, the idea was to bring the viewer inside of that reality in a very easy-going and natural way, so that you can sit and contemplate this foreign, inaccessible, and vanishing reality. It’s a lifestyle and an approach to reality that’s very fast disappearing from our planet. We though it’s interesting to observe and pay attention to how these people interact with reality, interact with the notion of family and spirituality, and just be a witness of that. We don’t try to explain anything, there’s no narration.

WATSON: I feel like the strength of this tool is more geared towards experiencing things that really exist so you’re brain lets you experience it that way, and also capturing the world—the world is changing so fast. This is probably the only way that we will be able to see later what it used to look like. I guess fiction would be interesting. A horror film would be terrifying; a horror film would be awful. I can’t imagine watching a violent scene; it would make me want to barf.

RAPHAËL: I think you’d be surprised. With VR, since you’re so much more vulnerable and you’re so much more present, you have to lower the volume. I think a horror piece would be so over-the-top. It’s challenging to even believe in subtle fiction, to get an actor to look like they’re not acting is the biggest challenge—and that was the biggest challenge in WILD. I think a horror film would quickly start looking like an amusement park ride.

WATSON: I guess for me there are so many things in this world that I would want to experience that way before I experience fiction, like I’d love feel the experience of the more dangerous street corner in America that you’d never have access to.

LAJEUNESSE: There’s also a meeting point between authentic reality and the dream state quality. Strangers is an interesting thing. There are many, many people who react to Strangers, which is a very authentic and real piece, in a way that is much closer to what we were talking about with the dream state than reality. Some people say it makes them feel as if they were totally in an alternate reality—it makes them feel like they’re in this abstract space.

RAPHAËL: You don’t live this rupture in space and time.

LAJEUNESSE: We’ve been showing Strangers to lots of people in the last year, and what strikes people is that they get into your own personal space and they generally comment that it’s messy.

WATSON: [laughs] I find it funny that people smell smoke when they see the smoking ashtray—you see people’s hands blowing the smoke away from their faces. My place isn’t always that messy. [laughs] Maciek and Chris were throwing stuff around my apartment to make it a bit messier than it normally is for the record, but whatever.

BROWN: How did you all meet? Were you friends before Strangers?

LAJEUNESSE: No, we were not. We tried to contact Patrick when we started virtual reality. When we had our technology and our approach pretty much ready, we started daydreaming about creating an intimate piece with a musician and that was Patrick. In our minds that was very, very clear from the beginning: we wanted to work with Patrick. We thought it would be a perfect match for the medium. At the time, no one talked about virtual reality, and we didn’t really know anyone else in the world who was doing what we were doing—we were just doing it from our own studio. We tried to contact Patrick, but he wouldn’t answer our emails. We met with Chris and Maciek, who are our friends and fellow directors and who Patrick knows. They got excited about VR and they called Patrick and we got to meet him and the project took shape from there.

BROWN: Why Patrick?

LAJEUNESSE: We love the music, but there is something about the guy—his presence, just the way he is. It’s something difficult to name exactly, but I guess you feel his soul when you meet him and through his music, and all of that is coherent and makes him someone who we were extremely curious about, and kind of a mystery. We thought virtual reality and him would be a perfect soul-match.

RAPHAËL: Different artists, different musicians, have different ways of being, of playing. There’s a level of genuineness about Patrick that we thought would be perfect. Not just any musician would have been right for this piece.

LAJEUNESSE: It’s definitely not a medium for all musicians. When we think about music, there are a lot of people who we don’t necessarily think would be a good fit for the medium. There needs to be a real sense of authenticity and not fabricated—there needs to be something solely authentic about the artist.

STRANGERS, HERDERS, AND WILD – THE EXPERIENCE, ARE CURRENTLY ON VIEW FOR FREE AT THE NEW FRONTIER BUILDING AT 573 MAIN STREET IN PARK CITY, UTAH, AS PART OF THE SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL. FOR MORE ON RAPHAËL AND LAJEUNESSE AND THEIR COMPANY FELIX AND PAUL, VISIT THEIR WEBSITE.

For more from the Sundance Film Festival 2015, click here.