The Keeper of Room

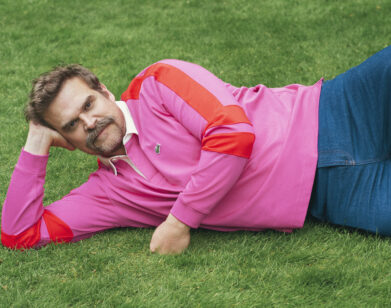

ABOVE: JACOB TREMBLAY AND BRIE LARSON AS JACK AND MA IN ROOM. PHOTO COURTESY OF A24.

For five-year-old Jack, everything in his room is personified: there’s Bed where he usually sleeps with Ma, and Wardrobe where he sleeps when Old Nick comes to visit through Door. Meltedy Spoon is Jack’s favorite eating utensil, Skylight his window into outer space, and TV his portal to things that are not real. This is as far as Jack’s world extends. He has never left Room or interacted with anyone but his mother Ma.

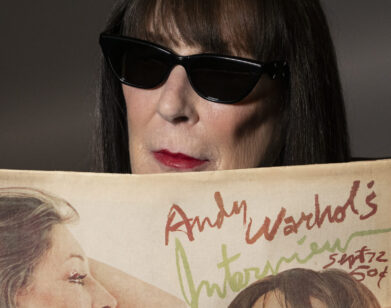

Jack and his mother are entirely fictional characters, invented by Irish-Canadian author Emma Donaghue for her 2010 novel Room. There have been a few similar cases in which kidnapped and imprisoned women have born and raised children, but very few for, Donaghue points out, “most psychopathic captors don’t want a child.” Donaghue is, understandably, resistant to draw parallels between her novel and real-life cases, but the seed of the idea came from reading an interview with five-year-old Felix Fritzl, whose mother gave birth to seven children during her 24-year imprisonment in a basement dungeon at the hands of her father. “A journalist asked Felix what he thought of the world, and they quoted him saying that the world was ‘nice,'” Donaghue recalls. “I remember thinking, ‘That’s a bit of a simplification. How could you possibly emerge into this brand new planet and describe it as nice?’ So I thought, ‘What lies behind that one word nice?'” Donaghue did not, however, limit her research to the lives of Elisabeth Fritzl or American kidnapping victim Jaycee Lee Duggard. “There are all sorts of analogous situations, like solitary confinement—they’ve studied a lot of prisoners to find out what the effects of solitary confinement are,” she explains. “I looked at situations where children from, say, Russian orphanages have been adopted into the West and they’re suddenly in this completely different world and there’s so much stimulus and so much growth and yet it’s so overwhelming. I looked into lots of situations that I thought would give me any insight to what Ma and Jack are going through,” she continues.

Last month, the film adaptation of Room premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. This week, it will open in limited release across the U.S. Directed by Lenny Abrahamson with a screenplay by Donaghue, Room is already receiving awards buzz for the performances of its two lead actors Brie Larson, who plays Ma, and nine-year-old Jacob Tremblay, who plays Jack.

EMMA BROWN: When did you decide that you wanted to write the screenplay for Room?

EMMA DONAGHUE: Before the book was published. I sold the novel and then I thought, “This could work beautifully on film and I want to write it.” So I did. I drafted it before the book was published, because I thought it would be easier to have a go without anybody looking over my shoulder or telling me what to do or telling me to give it to a more experienced screenwriter. There’s a long tradition of women being quite powerful within fiction and then men making the movies, so I thought I should have a bat first. Whenever I found the right director I could say, “I’m not asking you to hire me sight-unseen, I’m saying, ‘Here is my script, what do you think?” That’s how it worked out. Lenny [Abrahamson] was similarly direct; he wrote me a long letter and when we met he was really cards-on-the-table about what he wanted to do with the book. There’s been a lack of bullshit and game playing on both sides. It’s been an incredibly pleasurable process developing the project for several years with him rather than just selling the rights and walking away.

BROWN: Would you have done the same for your other books had someone tried to option them?

DONAGHUE: With my first book, I was hired to write a draft of the script. I was so young and less confident. They put me through seven or eight drafts and it was just getting worse and worse, and then the film was never made. There was a low point when—I was about 24—they said to me, “Ooh, the Dutch are going to fund it, but they want more sex scenes.” So I went back and I put sex scenes in just so the Dutch might fund it. That was a low point. Also, I remember the producer rang up and said that he saw a great joke on Sex and the City last night, and could I put that in the script. I didn’t say no to any of these things, so I’m glad that film was not made. I can’t believe I was that weak and passive about it. It felt, this time, like I knew what I was doing much more and I knew ways in which I was willing to compromise and ways in which I wasn’t. It’s a whole different story now. This has been such a great experience and I’ve learned so much from working with Lenny, and having a really direct working relationship with him. I think in big studio films, it’s really common to feel as if lots and lots of executives are between you and the director. In this case, it was a really small little circle of creativity. It’ll probably never be like this again. I keep saying to myself, “It’s not usually like this.”

BROWN: Screenwriting is a notoriously thankless job.

DONAGHUE: It is. And I can’t believe it’s getting all this attention, too. I know it’s probably because I wrote the book more than because I wrote the screenplay.

BROWN: There are some minor changes between the book and the screenplay. Were those all for practical reasons, or were any of them ways in which you would want to revise the book if you could?

DONAGHUE: No, it wasn’t that I wanted to change the book; it’s just that a book is not a time-based medium the way film is. Something I’ve always known from writing plays is that with a time-based medium like theater or film, you can’t have the audience getting restless in their seats. They’re stuck there on their bums; you have to pay enormous attention to pace and you can’t lose your way. A book has so much time; Jack can do things like meeting his grandmother’s book club—lots and lots of new characters and observations of different social settings. One of the first changes I made was to carve away a lot of the new characters in the second half, because you don’t need them. You need to follow that line of how Jack learns to trust other people. Even though he is, most of the time, in a suburban house with just a few family members, that’s already a complete transformation of his life. Most of what we had to do was whittling away unnecessary material in the second half.

BROWN: Were you on set during filming?

DONAGHUE: I was. Luckily they made it in Toronto and I live in London, Ontario, just a bus ride away, so I got to visit about once a week. I didn’t kid myself that I had any power on set—you’re on such a tight ticking clock at that point, you don’t want to do anything to slow anyone down. If I had anything to say, I would say it quietly to Lenny over dinner. On set I was really just being an anthropologist. I was going around interviewing everybody about what they do: “What is a grip?” It turns out a grip in Ireland is slightly different from what a grip in Canada is. There are all these national differences.

BROWN: Did you go through the casting process with Lenny?

DONAGHUE: Yeah. Again, I was more of an interested observer than really having any power. But I think I watched every film featuring a white woman between 20 and 30. It was hugely enjoyable. Because of the willingness of Lenny and his producers to include me in the circle, I got to see audition tapes. I got to watch the dailies. Even when I wasn’t on set, I got to have a look at what they filmed that day. I got to visit the additional dialogue recording; I got to visit the editing. I never felt kept at a distance.

BROWN: Jacob Tremblay, the child who plays Jack, is so brilliant in the movie.

DONAGHUE: Isn’t he? God, we’re so lucky. The whole thing would’ve fallen apart if we hadn’t found him.

BROWN: Were you confident from the minute he was cast that he was the one?

DONAGHUE: Well, the filmmakers were confident that they would find him, and as soon as we did find him, and in particular looking at his tapes, I thought, “This one is relaxed enough with acting that he could probably do this.” There was just a confidence. The fact that he had done two films—one in voiceover and one acting in person—I think that was a real help, because he wasn’t bothered by all of the technical requirements of repeating things and doing things from different angles. I never saw him complain about doing another take. The stuff is play to him.

BROWN: It’s interesting to hear people talk about what they want from child actors, because sometimes it’s just a kid that’s as close to the character as possible, and then other times it’s about having a high level of professionalism.

DONAGHUE: You want them to be a totally ordinary, real child, plus have a remarkable adult ability to understand direction and so on. You have to use different techniques. Lenny had to coax the performance out of him, because this wasn’t just a child behaving like a child; it was very specific stuff. Lenny decided to film the whole thing more or less in sequence, because that would allow Jake to understand where Jack was in the story at any one point, and Lenny talked to Jacob all the way through the scenes. He’d be like, “Okay. Here’s the bit where you move your leg and now you sit up.” So it wasn’t like filming with an adult where you just let them get on with it—there was a huge amount of gentle coaxing. Brie did a lot of that, too. Their performances are really symbiotic. She was his protective, motherly buddy. She would be reminding him of some rule, like don’t swing your feet, and she’d gently remind him in a way that was a joke between them, so it never felt like she was nagging. She, too, would help jolly the performance out of it.

BROWN: Did they spend a lot of time together before filming?

DONAGHUE: The company deliberately got the set ready three weeks early so that Brie and Jacob could play in there, get used to the space, and make it their own. They made all the crafts together, which you see, for instance. So I think building in time and space for that stuff was crucial. I think Brie really went out of her way to woo him. She had lego playdates with him. You can’t fake that stuff. Yes, there’s a chemistry, but with children it’s always a matter of putting in the time. You can’t make them have fun with you.

BROWN: I was reading a Q&A you did with some fans for The New Yorker, and you said that you realized that the author is always the Old Nick of their stories.

DONAGHUE: Yes, we’d like to think of ourselves of these kindly creator figures, but we are these evil surveying gods of our little universes. We like to throw problems at our characters, because otherwise there’s no story. [For Room] I was literally picking out their furniture on Ikea: “Oh, I won’t buy them the nice bed, I’ll buy them the nastier bed.” I gave them only five books each—that’s an act of cruelty. You’re always the one turning the thumbscrews. And oddly enough, doing the film felt like a bit of a relief, it felt like that job was handed over. Lenny’s ultimately in charge of all the pain and suffering these characters are going through. It was great to take a book that had been entirely about me, or rather entirely the contents of my head, and hand that over to a much wider team and say, “Okay, the story belongs to you guys now.” I think what helped was that so many fans had written to me giving me their own versions of the story, and each of them relating to the story passionately in their own different ways. Grandfathers writing to me saying, “It’s all about my love for my autistic grandson,” or women writing to me, “It’s my violent marriage,” or “It’s like my childhood in a religious cult.” I’ve had letters from China saying it’s clearly an allegory of life under a political regime. I’d seen that the story meant so many different things to different people and that it wasn’t mine anymore, so that made me all the more able to hand it on to filmmakers and say, “Let’s see what you can do with it.”

BROWN: Did this realization that you, as the author, are the cause of your characters’ woes change the way you approach writing? Is it harder to be cruel to your characters?

DONAGHUE: No, I’m afraid I still have a real relish for making them suffer. [laughs] That’s how narrative is produced. I’ve been in a long and happy relationship for 22 years and it’s never inspired me to write anything. It’s too good—nothing to say. Problems, conflict, that’s what makes for good stories. And besides, by the end, Ma and Jack are such survivors, I see a very happy future for them. I would feel bad leaving my characters to suffer forever; I usually lead them through the dark and into the light.

BROWN: With Room and a few of your other novels that are inspired by news stories, are those stories something that you seek out?

DONAGHUE: It seems to just happen to me. Room is very fictional, so I didn’t feel that the facts held me back at all, because I was only taking that one line, but my very fact-based novels, it’s double the work. There’s usually some moment when I’m struggling with the fact that there is no train from Paddington to Bristol just when I need there to be. Sometimes I’m like, “My life would be so much easier if I could just make this stuff up.” But I somehow get hooked by these real cases. I don’t know why; the little element of the real gives an extra almost forensic excitement to the process, because I feel like I’m trying to dig up the truth as well as using fiction to fill in those gaps. Writing is nearly always a matter of finding whatever your brain needs to trick it into being creative, and in my case, a tiny little bit of fact just seems to work.

BROWN: How do you find these stories to begin with?

DONAGHUE: I read a lot of social history. If I’m in an art gallery and a picture intrigues me, I immediately write down the title and I google it. I do a lot of googling and looking out for good stories. I can almost smell them sometimes. When people write to me with stories, they are never ones that work for me. There’s something mysterious about which ones catch you. It’s also got to be a story about which something is unknown; it can’t just be, “This happened.” There has to be some big question like, “How on earth would you parent in a locked room?” It’s kind of perverse when you’re researching historical fiction, you try and find the facts—I’ve sometimes spent an entire day in a library trying to find something and I go home going, “Great, I didn’t find it, so I get to make that thing up.”

ROOM COMES OUT TOMORROW, OCTOBER 16.