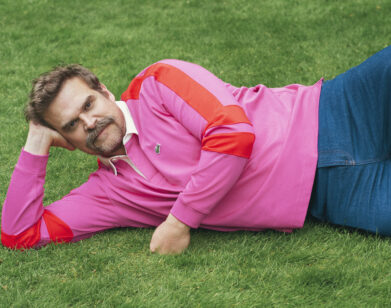

David O. Russell

THERE WAS A PERIOD WHEN I KIND OF HAD TO REINVENT MYSELF . . . I’D LOST MY WAY CREATIVELY, AND I WAS HUMBLED David O. Russell

David O. Russell’s filmography neatly divides into two parts: There are the four-and-a-half features that he directed before 2010’s The Fighter, and then there are the three—including The Fighter, Silver Linings Playbook (2012), and his latest, American Hustle—that he has directed since. (The pre-Fighter half-film is an unfinished one entitled Nailed, which was partially shot, with Jessica Biel starring as a woman who accidentally gets shot in the head with a nail by a construction worker, inadvertently sending her libido into overdrive. Production was halted when the movie ran into financial trouble, and despite a cast that included Jake Gyllenhaal, Catherine Keener, and Tracy Morgan, and a script co-written by Kristin Gore—Al and Tipper’s daughter—it was never completed.) The nominal difference between Russell’s pre-Fighter and post-Fighter work is that in the earlier part of his career, he was making quirkier, more niche-oriented movies that were either darkly comedic, like the familial twisters Spanking the Monkey (1994) and Flirting With Disaster (1996), or eerily prescient, like his underrated Gulf War heist flick Three Kings (1999), or wildly, weirdly esoteric, like the parabolic existential tract I Heart Huckabees (2004), and now, he makes movies that a lot of people see and which occasionally get nominated for or win Academy Awards. (Russell received nominations for best director for The Fighter and Silver Linings Playbook; both of which also garnered best picture nods; Christian Bale and Melissa Leo won best supporting actor and supporting actress respectively for The Fighter; Jennifer Lawrence, of course, won best actress this year for Silver Linings Playbook.)

The more accessible emotional content of Russell’s recent films is often pointed to as a factor in this tectonic shift; after all, on the surface, it’s easier to relate to a boxer trying to fight beyond his station in life in The Fighter, or to people trying to navigate personal disorders, both mental and literal, in Silver Linings Playbook, than it is to watch a confused college student embark on an incestuous relationship with his mother (which, if you haven’t seen it, is what happens in Spanking the Monkey). But maturity is too hierarchical a word to trace Russell’s growth as a filmmaker, since he has always made powerful movies, and evolution far too vague to describe the vividness of his transformation. The fact is, the older films are just as good as the newer ones, and the newer ones are just as angular as the older ones. It is, however, instructive to know that before Russell turned to making movies full time in his thirties, he worked as a political activist and organizer, which means that he probably understands, on some very basic level, how it’s sometimes necessary to kick at things in order to change them—and that sometimes the thing that needs kicking and changing is you. If there’s an idea that seems to reemerge in his films in different iterations, it’s characters running to extremes, even as they grasp at commonalities—a struggle, in many ways, not dissimilar from the eternal tug-of-war between being saying what you want to say and being understood that Russell himself has negotiated so expertly as a filmmaker.

Russell’s latest film, American Hustle, out in December, takes as its backdrop the infamous Abscam FBI sting in the late 1970s and early 1980s that ultimately unraveled webs of corruption amongst public officials, resulting in the convictions of a U.S. Senator, six members of the House of Representatives, and a number of others. He uses these events as the basis for a fictionalized story centered on Irving Rosenfeld (Christian Bale), a con man, and his British partner, Sydney (Amy Adams), both of whom go to work for undercover FBI agent Richie DiMaso (Bradley Cooper) as part of a similar sting in which they all become entangled in ways that none of them envisioned. Lawrence and Jeremy Renner also appear in the film, as does Louis C.K., who spoke with the 55-year-old Russell recently in Los Angeles.

LOUIS C.K.: Can I ask you why this movie is called American Hustle?

DAVID O. RUSELL: Because everybody in the movie is hustling. They’re hustling in a couple of senses: either in trying to get by and make something happen in a conning way, or in how we all kind of somehow have to use white lies or emotional stories that we tell ourselves to get through our everyday lives. I feel like everything is a form of storytelling. You can tell yourself a story about your marriage or your relationship, and it can be that story. But then, on a certain day, for whatever reason, that story stops cutting it, so you have to make up a new one. That’s happening in the relationships in the movie, the love affairs, as well.

C.K.: But do you take part in the hustling? Do you hustle yourself or hustle other people? Are you a hustler?

RUSELL: Well, I think that everybody does that in order to survive. That doesn’t mean lying—it’s more about how you handle situations.

C.K.: When in your life do you find yourself hustling?

RUSELL: On a daily basis? I think sometimes you have to handle things delicately at work or at home. You know, you can find yourself in situations that are like opening a closet filled with bowling balls that are going to fall out of it, but if you handle things graciously, then that’s not going to happen. What about you? When are you hustling?

C.K.: Wait a minute—you still haven’t answered my question. You keep abstracting it and projecting it. Give me a situation in your life where you have actually had to hustle. Is there anywhere in your life where you feel that you hustle? You, David—specifically. When have you hustled?

RUSELL: I can’t give you broad answers on this?

C.K.: Well … No. Try starting the sentence “I” instead of “you.”

RUSELL: I guess, in one sense, the kind of hustling I do is like in Silver Linings Playbook, where the character says, “If you stay positive, you have a shot at a silver lining.” That is a story he is telling himself, and he’s hustling himself for good. He can tell himself a negative story, but it would destroy his life. So every day, when my feet hit the ground, I have a story that I’m telling myself that I choose to make a positive story. I know people who don’t do that, and there’s a heavy energy around them. So I guess there’s that kind of hustling. And then also there’s my son, who is helping to write his own narrative every day. But in terms of more con-type hustling, no, I can’t say that I really do much of that during my day. You know, I was talking to my dad about what happened to his business in the ’70s, because I have a great affection for that era and we were always big fans of his. He worked at Simon & Schuster from the time he was 18. He was in their stock room, and then he became a salesman and, eventually, a sales executive. And then, in the ’70s, there was something that happened where this whole group of guys that he was a part of got pushed out, and another group of what I would say were more crafty guys got in. When that happened, it rocked our house—and it was very educational for me. So I can completely identify with the fact that Christian Bale’s character, Irving, in American Hustle feels the way that he does about his dad. Irving says his dad was honest to a fault, and that his dad maybe got taken advantage of. So I understand that feeling. And then I also understand his father’s feeling of, “You should stay on the straight and narrow.” That’s where a lot of this personally comes from.

C.K.: And the first thing that Irving identifies as a driving force in his life is what happened to his father.

RUSELL: Yes, that’s right. I mean, some of our movie is based in truth and some of it is fictionalized—I would say that a lot of it is fictionalized. One thing that is true is that the guy who part of the film is based on, his dad did run a glass business in the Bronx, and this guy did feel that it was hard for businesses to survive if they didn’t resort to certain practices.

C.K.: That’s interesting to me because in talking about what it means to hustle and to survive, all of the examples that we’re discussing seem to start with somebody else. Christian Bale’s character loves his dad, his dad gets screwed, and that changes the way he approaches life. You talk about your son, you talk about your dad. It’s like hustling is not a completely selfish thing—that the reason why you hustle can be connected to your feelings about someone you’re close to and how that motivates you. When did the story that you tell in this movie become one that you felt you had to tell?

RUSELL: Well, I’ve wanted to tell a story set in this period for many years, and I’ve written some scripts set in this period that were never produced. But then a few years ago, I started speaking to the writer Eric Singer, who wrote the first draft of the script for American Hustle that I eventually rewrote. So I would say that it was around then that this specific story became one that I wanted to do. But I remember very well the period when all the stuff that happens in the movie went down, and I remember a lot of the music and a lot of the feelings that were in the air at that moment, so I started rewriting the script, really, coming off of The Fighter and Silver Linings. I was inspired by what we had done with the characters in those films, and that is what first attracted me to this story. The Fighter or Silver Linings were about the people first and foremost, and so with this one, I wanted to create a character that I knew was going to be like napalm for Christian Bale—one that I knew would be hard for him to resist because it was going to be such a great character. And then I also knew that Bradley [Cooper] was going to be interested in playing a transformational character like the one that he does in this movie, which I think is a big step for him—he’s playing an agent, but he’s a guy from the outer boroughs, and it’s a very specific character that he hasn’t played before. It turns me on to think of every actor playing people they’ve never played before. I love the idea of getting Christian to be soulful and funny as well as intense. I love the idea of getting Amy Adams to be hot and sort of mastermind-ish as well as really emotional. I love the idea of seeing Bradley become an almost kind of intense bad guy but a very complicated one with a lot of heart. And then you see Jennifer Lawrence as a housewife on Long Island, young and unhinged, but in an inspired way—you’ve never seen her that way before. And then [Jeremy] Renner as this New Jersey guy, a mayor with a big Italian family who loves his community … There was a recession then, just like there is now, so everybody was trying to be creative in trying to make something happen …

C.K.: Do you think Renner’s character is hustling?

RUSELL: Absolutely. I think someone who is trying to take care of a community hustles every day. His character has a community that was turned into kind of a ghetto during the ’60s and the ’70s, and he loves it passionately so he’s trying to generate income for it. He wants to get investments from wherever he can—even if that means that he has to do some things that he considers the cost of doing business, which I think happens today on a grand scale of hundreds of millions of dollars. But I think back then, it was almost quaint that it was happening on this smaller scale. He was just trying to get some investments going, but this guy was also a state senate member and one of the people who pushed to make gambling legal in Atlantic City. He wanted to rebuild the city, to renovate these beautiful old hotels, which would put a lot of people back to work. These people are a bunch of dreamers—and I love dreamers.

C.K.: This movie takes place near the end of the ’70s, like, right before the U.S. won that hockey game against the Soviets. I remember that everyone I knew back then worked in fast food or something, and then a step up from that was working for the city paving roads or something that was also dead-end, and everybody just wanted somehow to get to some other level where they’d have more control over their lives. I do remember the word hustle being used a lot at the time, but it wasn’t a negative. It wasn’t about lying. You admired somebody for hustling back then—it was a virtue, like in sports, “That guy really hustles …”

RUSELL: Like Pete Rose—Charlie Hustle. Unfortunately, that name did take on a different meaning for him later. [laughs] But before he got into any trouble, it just meant that he was a guy who would dive into a base headfirst and would do anything to stay alive. That’s what everybody is doing in this movie.

C.K.: Hustle always means doing more, going further than what your job is supposed to be and what you’re given to do. People hustle for their families, for people around them, for their communities in the way that the Renner character does. So hustle also sometimes means adding facts to your reality that aren’t there—and sometimes doing things like taking money that’s not really yours and things like that.

RUSELL: Yes, exactly.

C.K.: You were saying that the actors in this film are all playing characters they’ve never played before, and one thing that you do become aware of a few times in the movie—in a great way—is that everyone is pretending to be somebody else. In other words, they’re all acting in three layers. Christian Bale is pretending to be a guy who is pretending to be a guy. Amy Adams is pretending to be a woman who is pretending to be someone else. So the people we’re watching in the movie are like second-layer people, and there are other people underneath that we’re not seeing in the movie except for in certain places.

RUSELL: What I also like is that people are deciding who to present themselves to be in love affairs as well, so it isn’t just about commerce. Christian’s and Amy’s characters are very much in love, but Christian is dealing with a complicated relationship with Jennifer, and then Bradley Cooper starts to fall for Amy’s character. So it starts to get complicated. It’s a sexy time.

C.K.: Christian’s character and Amy’s character, Sydney, are supposed to be in love. But are they actually in love? Or are they people who are trying to become in love?

RUSELL: That is an interesting question. That is probably the most interesting question that anybody can ask at any time. I think that most relationships have both of those things going on. There’s the you that you want to be or can be with the other person, and there’s the you that you just are all the time.

C.K.: You almost want to say to the person you’re in a relationship with, “The person who I’m pretending to be loves the person you’re pretending to be.”

RUSELL: It’s a moving target because it keeps changing.

C.K.: And then Bradley’s character, Richie DiMaso, forces them to hustle into a whole other league of pretending.

RUSELL: Speaking of going to another level, I thought you fit in nicely with all these people as this sort of Midwestern ice-fishing boss of Richie.

C.K.: Well, when you and I first talked about this, you told me the sort of world of it and who I was playing and how he fit in, and my feeling was that this guy was the only person who was not having these problems that the other characters were having. My guy doesn’t have layers. He doesn’t have to figure out how much of himself to use or how to call another person out. He just does what he’s supposed to do. It’s interesting because I was watching the movie while my kids were doing their homework, and when it was over, I said, “I’m so relieved that I don’t break laws. I’m grateful that I don’t have to worry about the shit that these people in the movie are wrestling with.” That’s probably why I had a good time playing that guy—I think he felt that way, too. It’s like, “You people are nuts. You’re not supposed to be doing any of these things that you’re doing. None of this is okay. You’re supposed to be yourself, be honest, follow the law, and take less out of life.”

RUSELL: Take less out of life?

C.K.: Yeah. You’re not supposed to become something else so you can get more. You’re supposed to stay you and get through as yourself, because at least then you can count on that, and you don’t have to ask yourself who you are half the time. So my guy was a lot simpler to play. It was good playing with Bradley because he is so unhinged and laser-like and passionate, and it’s really fun to be somebody’s roadblock. He’s burning in every scene, and I’m simply saying, “No, you can’t do this”—it’s making him crazy. It was fun to be the tool that drove him to distraction that way. Because I’m a comedian who sometimes tries to act—that’s what it would say on my business card—the thing that’s interesting about doing movies like this one is that these are real actors, so it’s like getting to watch a movie up close. You feel like you’re really in the scenes. I would forget that this was Bradley Cooper or Christian Bale. I was completely in the scenes with these people because they’re just so good. I’ve never done this before, but I did steal one thing. In the scene where Bradley and I are yelling at each other, and he says, “I’m going to call your brother,” and I go, “He’s dead,” I definitely stole that from Robert De Niro in that movie about the blacklist.

RUSELL: Guilty by Suspicion [1991], the Irwin Winkler movie?

C.K.: Yeah. There’s a scene in that movie where he’s in a congressional hearing and they go, “Oh, you knew this woman was a Communist?” and De Niro’s character goes, “She’s dead.” It’s also how he says “dead” in The Untouchables [1987]. It’s the way that he says “dead” that I stole.

RUSELL: I had no clue. Did you meet Bob when he was on set?

C.K.: No, I was never anywhere near him. He, by the way, is terrifying in this movie. He’s a really upsetting character.

RUSELL: I like that Bob shows up in the movie. It’s interesting to try to make him terrifying in a new way.

C.K.: Talk to me for a moment about the music and the cinematography in American Hustle, because this is one of the better-sounding and -looking movies I’ve seen in a while.

RUSELL: The look of this movie is very lush. I think the designers really knocked it out of the park. Michael Wilkinson, with the costumes—I mean, Amy Adams, who has literally 50 wardrobe changes, has never been this glamorous. But everybody’s style is just amazing, but also very real. And then Judy Becker with all the sets … How the film looks, how it’s shot, is very important to me. It’s important to me that you feel the lushness when you watch it. And the music—going back to The Fighter, that has been very important. But whether it’s Frank Sinatra, Johnny Mathis, Led Zeppelin, or the White Stripes, music creates a world of enchantment, and enchantment and romance are very important to me. I want people to spend time with these characters in their world and just kind of love it.

C.K.: It was also interesting to me that your camera was always moving. There’s all this digital stuff now, but American Hustle was shot on film, and when film is running through a gate, you’re very aware of it because it’s so expensive. But you never cut. You just roll and keep shooting until 12 minutes later when the stuff rolls out, and between takes, everyone has to reposition really fast. It created a tension on the set that is really healthy and very creative.

RUSELL: De Niro said the same thing on Silver Linings, and now I understand better what he meant. Life, when it’s going down, is intense. But I guess it’s because we’re burning film. The day is going by, so you can’t let your guard down.

C.K.: The way you work is more like soccer than football. In football, you talk and huddle and stop and switch people out and substitute and go again. But in soccer, you just keep moving. When we were on the set, you were just so passionate. There were moments where you’d be yelling to us as we were acting. Sometimes you would yell out somebody’s line because you were so wrapped up in it. And this was all a tremendous example for me of a director who really cares about the work. At one point, I was doing a scene that’s not in the finished movie, where I’m telling this crazy ice-fishing story, and you told me to go deep down and sound like Satan and really get low in myself. I was embarrassed and kind of laughed, like, “How am I going to do that?” And then you said, “Go big or go home. What are we here for? This isn’t like, Let’s just hang out in this room for a while then go home. This is big shit.” It was inspiring. I’ve actually taken to that myself. I’ve said it a few times on the set of my show—”Let’s go, guys. Go big or go home. This is not worth doing in half measures.”

RUSELL: I’ve learned a lot from watching your show, so it’s a mutual inspiration society. We’ve also both worked with Melissa Leo. I would say the two things that Melissa Leo is most known for in recent years are The Fighter, for which she won an Oscar, and the episode that she did of your show, which she’s almost become more famous for.

C.K.: You said something else that’s stuck with me, too, though. You said, “You’re just hitting your stride.” It’s something that I’ve thought about a lot because you’re learning through all this, putting movies out that are reaching a whole lot of people, getting a lot of attention, winning awards for all kinds of people in the movies. So where do you think you are in time line? You started with Spanking the Monkey, which was such a small, personal film, but really scary. I saw it at the Angelika in New York City. John Leguizamo was in the theater, and in one of the scenes where the kid and the mom are starting to step into scary territory, he yelled out, “This is like a fucking horror movie!”

RUSELL: [laughs] Oh, god.

C.K.: It was hilarious. I think I might be adding the “fucking”—I think he said, “This is like a horror movie.” Everybody laughed, though. But that was already a big movie. Here’s a young filmmaker, and he’s making a movie that involves a subject that no one else wants to touch, and yet it’s beautiful. It’s a very warm movie with a lot of humor. So you started here, and then you’re learning, and eventually, you get to this one-two punch with a hook of The Fighter, Silver Linings Playbook, and American Hustle. Where would you say you are now as a filmmaker?

RUSELL: I feel like this is a new incarnation for me, one that started with The Fighter. There was a period when I kind of had to reinvent myself—talking about reinvention, which is what I think the film was about. But in order to do that, you have to dig deep and look at yourself. I’d lost my way creatively, and I was humbled, and so I think I got really basic about wanting to depict people in the ways that I find them amazing and funny and emotional and that I can relate to and do from an instinctive, gut place. People trying to survive … That’s what all these movies are about. And then Silver Linings, to me, was a companion of The Fighter because, again, it’s a picture about families in a neighborhood. Romance is also part of it—an important part. And then this picture, American Hustle, exists as a bigger canvas, with many more characters. But I feel like I’m still on the upward climb. You know when you’re hungry and excited and you feel humble about it? I like that. In the past, when things were not clear, I think I wasn’t … I didn’t have my feet on the ground as much, maybe, 10 years ago. So I just feel like this is a good place to be now, to feel that you want to tell stories from this place and that you’re excited to tell stories from this place because you know what you love. I know what I love right now. I love these kinds of people and these kinds of worlds.

LOUIS C.K. IS A NEWYORK–BASED COMEDIAN AND ACTOR, AND THE WRITER, PRODUCER, DIRECTOR, AND STAR OF LOUIE,WHICH WILL RETURN FOR ITS FOURTH SEASON ON FX IN 2014.