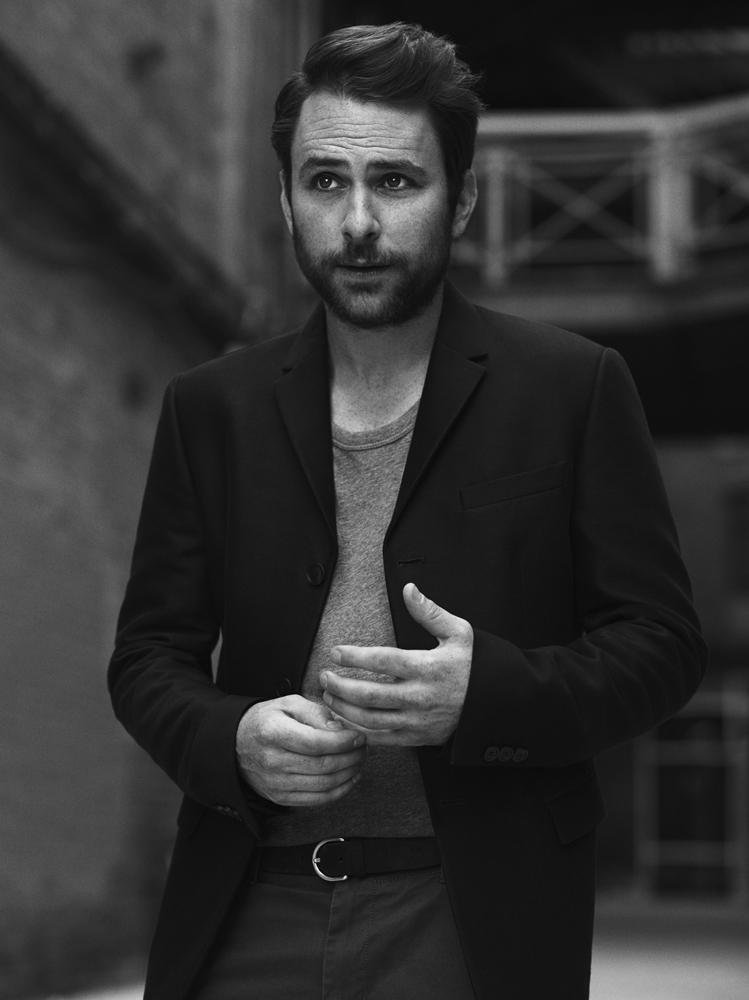

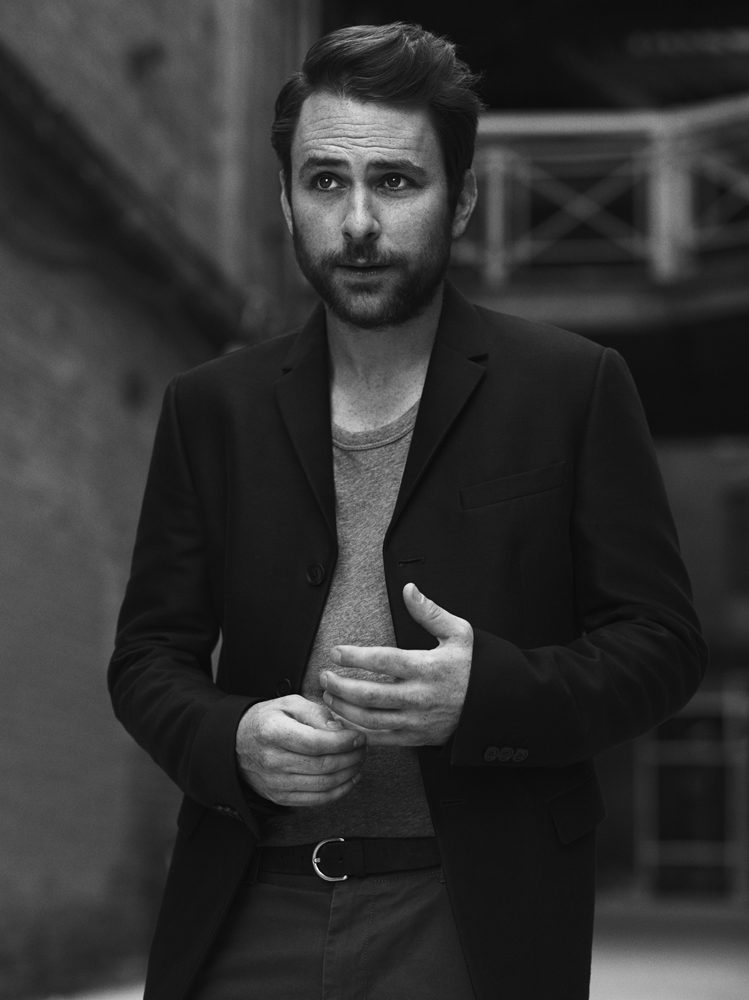

Charlie Day

CHARLIE DAY IN NEW YORK, SEPTEMBER 2014. SUIT AND BELT: EMPORIO ARMANI. T-SHIRT: T BY ALEXANDER WANG. PANTS: GAP. STYLING: IAN BRADLEY. GROOMING PRODUCTS: LAYRITE, INCLUDING SUPER HOLD POMADE AND GROOMING SPRAY. GROOMING: RHEANNE WHITE/SEE MANAGEMENT.

I had gotten to the point where I just didn’t want to perform anymore—I didn’t want to be on the chopping block anymore. that’s the thing about performing, you give yourself to the world for people to either praise or destroy. CHARLIE DAY

In his commencement speech this past spring at his alma mater, Merrimack College in North Andover, Massachusetts, actor Charlie Day regaled the assembled crowd with tales of his undergraduate pranks, delivered jokes on the community of honorary PhDs, which he was then joining, and told the story of his unlikely ascent to a kind of Hollywood stardom. Having been cut from the college’s baseball team—the story goes—and offered a too-good-to-be-true job at a bank in Boston, Day faced that age-old conundrum for creatives the world over: play it safe or risk it all. “Well,” Day said, “having a plan B can muddy up your plan A.” So he turned down the safe, square gig, and moved into splendid squalor in New York to pursue his dream of acting. “If I was going to run the risk of failure,” he said, “I wanted to fail in the place I would be proud to fail, doing what I wanted to do.”

In very short order, in 2004, Day and his friends in New York pitched, sold, and then began filming a super lo-fi sitcom called It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia for the FX network, and his grand wager began to pay off. Ten years hence, Sunny is a kind of cult smash (not Friends, but still running, supported by a passionate fan base), and Day is stringing together a series of roles in hit films, including the silly-fun comedy Horrible Bosses (2011) and it’s sequel, out this month. Distilling the affable idiocy of the Charlie he plays on Sunny and translating it to the big screen, this bumbling but endearing character has, somewhat ironically, become a signature for the 38-year-old actor who grew up in Middletown, Rhode Island, with two academics as parents. In 2013’s mega-movie Pacific Rim, he gave this character a scholarly spin, playing a hypercaffeinated scientist obsessed with the inner workings of the intergalactic monsters that were wrecking the world (another role which looks destined for reprisal, with Pacific Rim 2 getting a green light earlier this year). As Day tells his Rim director and onetime Sunny cameo star, Guillermo del Toro, these successes are all gravy, so long as he doesn’t have to wait tables.

GUILLERMO DEL TORO: Here I am, Pappy McPoyle [del Toro’s cameo character on Sunny] interviewing his creator. It’s a sequel to when [on the show] we negotiated the ransom of my father through the telephone.

CHARLIE DAY: [laughs] I know you don’t like talking on the phone.

DEL TORO: Every phone call I got during the making of Mimic [1997] was a terrible phone call, so that experience left me with phonophobia. How absolutely insane it is that there is a Sunny knockoff [It’s Always Sunny in Moscow] in Russian? It’s good to give back to the land that gave us Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy.

DAY: Isn’t that the craziest thing? They made it a few years ago and sent it to us—I guess for our approval—and we thought it was pretty great. The only significant change was that Mac’s character was named Roman or something, and they just called my character Fatso.

DEL TORO: Is it an easy transition, for you, to go into character—such dissimilar characters: Newt Geiszler [Day’s character in Pacific Rim] was too smart for his own good, and your character in Sunny is too stupid for his own good? Or is it something that requires you to go through technique? Or do you find any acting tricks that come from your theater days?

DAY: In my theater days I assumed that you had to get rid of yourself to do a character well, and I don’t think I was a very good actor when I did that. I would watch my favorite actors in movies—Sean Penn can really transform from movie to movie, and yet, there’s always the Sean Penn that you recognize in those characters. There are times in your life when you feel like the dumbest man on the planet and you’re insecure about something, and then there are times where you feel like, “Hey, I’m a pretty smart guy and I’m pulling it together …” For me, it’s just been a matter of identifying those emotions.

DEL TORO: People tend to confuse you with the persona on the screen, and what amazed me is that your background is almost academic, with a particular fixation on music. What kind of kid were you?

DAY: I think we’re all guilty of mistaking the actors we’ve seen over and over again—we think we know them. And the characters on Sunny and Horrible Bosses, they’re both pretty dim. I think people are surprised when I string two sentences together. But, you’re right, I had a fiercely academic upbringing. My parents are both PhDs, and my sister has a PhD in music theory. That was my track early on. I had my own insecurities, which a lot of my comedy would come from, about not being able to live up to their academic expectations. Acting out those insecurities was a way of confronting them, like, “Let me just lean into being a guy who can’t read or write.”

DEL TORO: The academic background you have is so orthodox and your comedy is so iconoclastic, so anarchic. Did your parents find the brand of comedy that you excel at and enjoy shocking?

DAY: I don’t think so. I mean, they took me to Woody Allen movies. Of course, Woody Allen has his classy movies—Annie Hall and Manhattan—but there are his dirty movies too. And our brand of comedy was the next generation. But because the episodes always have a point of view, my parents were able to see that and not be offended by it. I’m always afraid of the viewer who is offended by it—they strike me as the real philistines. [laughs]

DEL TORO: Many of Woody Allen’s comedies have a meandering structure, almost flow-of-consciousness. From there you go to the nonstructural stuff like Seinfeld. And Sunny has famously been called “Seinfeld on crack.” I think this comes from the fact that you were doing it on your own with friends, recording things that were a little more coarse and more immediate. Is that correct?

DAY: I think so. And even more specifically with Curb Your Enthusiasm and the British version of The Office, two shows that felt so lo-fi, like somebody walked into a room with a camera and a couple of actors and a funny point of view. Based on those two shows, we knew that we really didn’t need any special equipment to do it. We just needed two halfway decent cameras. It didn’t look like Pacific Rim, but it didn’t look like home video.

DEL TORO: It’s true. What makes Sunny so immediate—this almost nonfiction TV approach to improvisational comedy—is only possible when you have the accessibility of video, where you don’t have to have 150 people in the crew. It allows you to explore everyday vileness, I would say. [laughs] I suspect that some of your tempo and ear for comedy does come from knowing music, because ultimately, comedy is all about timing and about rhythm. Do you find that each project feeds your acting, giving you a new set of tools?

DAY: Absolutely. As an actor, I think every moment in your life is giving you a new set of tools. You’re constantly absorbing new information that you can put back onto the screen. And a lot of what I took from Pacific Rim was the way you directed, and the way you used the camera. In fact, I came back so charged up after having worked with you that, for your episode of Sunny, we did two versions of every single take. We did typical sort of Sunny shooting style and then we did the Guillermo style. Every single Guillermo shot wound up in that episode, and it’s one of my favorites.

DEL TORO: You hit at a time when most people are trying to figure out what they want to do. I call that time the “Age of Doubt,” the age in which you are chronologically an adult but you are still a little bit aimless and full of doubt. When did you make the decision that “I’m going to be an actor,” and how long after that decision was the show picked up?

DAY: I was in college and I had been cut from the baseball team. I signed up to start doing plays and taking some classes. They didn’t have a proper theater program but someone told me about the Williamstown Theatre Festival, and I applied. It’s a summer program and there are a lot of professional actors. I was helping to build sets and empty garbage cans, and I had been cast in a play—I had one scene with Scott Wolf, the actor from Party of Five. Campbell Scott was in the play, Robert Sean Leonard, Hope Davis, all these great actors. Paul Newman was coming to our rehearsals and just hanging out.

DEL TORO: Dear Lord!

DAY: I know! I was so intimidated. I was 21. I thought, “Boy, this could be fun.” I didn’t know if I could do it, but I had a do-or-die moment while I was taking a shower. I said, “You know what? I’m gonna play this scene.” I was supposed to pick a fight with Scott Wolf in the scene and I thought, “I’m gonna play this like I’m gonna rip his throat out of his neck.” I go up, I get an inch from Scott’s nose, and I can see a look in his eyes, like, “What is this kid doing?” [laughs] Of course, there’s a moment of fear where you think, “Do I back off, or do I just dive 100 percent?” I just dove and the director pulled me aside at lunch. I thought, “Oh boy, here we go.” And he said, “Paul just said, ‘An actor is born.’ ”

DEL TORO: Wow.

DAY: It was a really special moment. Where I grew up in Rhode Island, no one went on to be an actor. I didn’t know anybody in the business. It was this fictional thing. So to have a moment like that, that’s when I knew. I think I wanted to be more like an Al Pacino or Dustin Hoffman. I got my foot in the door doing episodes of Law & Order or Third Watch, and that was great, but I always loved to make people laugh. When we got together and made the show—we shot the pilot when I was 27, and it was picked up when I was 28—we didn’t know if it was just going to be seven episodes. We certainly didn’t know it was going to be the hit that it was. I didn’t know that it was going to launch a quote-unquote comedic career. I just wanted to do anything other than wait tables.

DEL TORO: In the first few seasons of Sunny, you almost do an inventory of what rules to break and, at the same time, maintain the quaint conventions of a sitcom—the bar setting, the canned music. Did you guys discuss the lineage of Sunny as to how it relates to sitcoms and those conventions?

DAY: We were kind of playing ourselves—young, struggling actors—and the humor was that they were these despicable, backstabbing actors. FX felt as though there was too much out there about the industry already. So we thought, “Okay, what kind of profession do these guys have to be despicable like this?” And we decided it would be better if they had no excuse.

DEL TORO: The way you play [the Sunny character] Charlie is, I insist, very much like a musical instrument. In your case, it would be a trumpet. [laughs]

DAY: A trumpet somebody dropped a few times.

DEL TORO: Danny DeVito is quite fantastic. He can create something as sociopathic and misanthropic as The War of the Roses [1989] or be part of a movie like Ruthless People [1986] and a model sitcom like Taxi. Did he ever attempt to deviate the dynamic of the show?

DAY: I think Danny came to us in a different time in his life, where he just wanted to be part of someone else’s creation. At no point in the 10 years we’ve been doing the show has he said, “Hey, I think we should do it this way.” I’m so eternally grateful to him for the lengths that he’s been willing to go to for us—like birthing himself completely naked from this couch in our Christmas episode.

DEL TORO: It’s almost like Tourette’s structuring, because there is absolutely no self-censorship. When you go to Horrible Bosses, say, does it take time to adapt to new co-stars like [Jason] Bateman and [Jason] Sudeikis, or is it an easy vacation from the other way of telling stories?

DAY: The two Jasons and myself, in the first film especially, were pretty close to what we do on Sunny—three guys in over their heads and bumbling through the world. My scenes with Jennifer [Aniston], not so much. But a good joke is a good joke, whatever the format is.

DEL TORO: You said something to me about what you liked about the movie—it’s a very great insight, which I used on [del Toro’s forthcoming film] Crimson Peak. You said, “Whenever it was Jason and Jason and me, it was not considered a group shot; it was considered a close-up, because we were such a strong unit.”

DAY: The characters had come together to make a three-headed dragon, three characters coming together to make one voice, or one piece of music. To isolate them, take by take, makes the audience feel manipulated. It’s more interesting to just put them all in one shot and forget about the camera for a second. That goes back to Woody Allen. I was watching The Purple Rose of Cairo [1985] recently, looking for some director tricks, and some of the scenes play out all in one shot. Not like a Scorsese or a Paul Thomas Anderson one-shot; it’s not going in and out of the swimming pool. It’s just the camera sitting there, serving life for a moment.

DEL TORO: We always said Newt is the star of his own movie, and you played him with the grace of a leading man. You know, I cast you off the “rats” monologue in Sunny, and we never ever referenced the show.

DAY: There were scenes where we wouldn’t even come close to talking about humor. You would push me around and be like [in del Toro’s accent], “I want you to be agitated!”

DEL TORO: You did your big monologue, like, 24 times.

DAY: In the script there were jokes, and you told me that you wanted me to do it as if I just got out of a prison camp in Vietnam.

DEL TORO: Trembling and crying.

DAY: Fortunately it took you guys five and a half hours to light it, so I had some time in my trailer to work on it. Also fortunately, The Deer Hunter [1978] is one of my favorite movies, so I got in touch with my inner John Savage.

DEL TORO: Nearing the horizon of Sunny ending, has there been a pivotal moment where something changed for you?

DAY: Becoming a father was pivotal in terms of prioritizing this career stuff, not putting it on a pedestal. Have you had a pivotal moment like that?

DEL TORO: I’ve had a few. You live and die two or three times making a movie. First, you write it, and the first pivotal moment comes when you can get it made. The second is in the process of making it, when the movie reveals itself to you, its flaws and its virtues. Then the most unnerving moment is when that movie is then launched into the world. It’s like bringing your kid to the first day at school and somebody points out that it has bowlegs, it is cross-eyed, or it’s gorgeous. You feel very exposed.

DAY: Your demeanor when we were doing press for Pacific Rim completely changed from the lovable, jovial guy you are to a man who seemed as though someone was sticking a thorn into his back. And I don’t blame you, because you’re out on a limb.

DEL TORO: I just find it unnerving. I mean, Pan’s Labyrinth [2006] got a standing ovation at Cannes that lasted over 20 minutes. About five minutes in, it got really uncomfortable for me. Five minutes is a long time, 10, longer, and so forth. But Alfonso Cuarón turned to me and said, “Relax, man, enjoy it,” and I was able to exhale for the only time in my life and enjoy it.

DAY: I had gotten to the point where I just didn’t want to perform anymore—I didn’t want to be on the chopping block anymore. I started to want to withdraw and retreat from it. Because that’s the thing about performing, you give yourself to the world for people to either praise or destroy. And I had to go and have a chat with someone about that. The guy I talked to is so wonderful—he was able to basically explain to me that actually I did want it and those gut feelings I was feeling was like a kid on Christmas morning: I was so excited that I had taught myself this sort of fight-or-flight response. I thought what I was feeling was flight, but the truth was I wanted to get out there and fight, so to speak. That was a real pivotal moment because it changed me. I hosted Saturday Night Live and I didn’t have an ounce of fear, because this guy really helped me train my mind. I gave a commencement speech this year and I had a similar experience where I said, “I should do it,” and then I had a full-on panic attack that I was actually going to have to do it. [laughs]

DEL TORO: The same technology that gave birth to Sunny has made opinion equally accessible and democratic. You may occasionally be hurt by the sort of cavalier cruelty of commentary if you go into online forums, so there’s definitely a maturity about not seeking validation from everyone, every single time. You need to adjust your compass to an obtainable goal. At the end of Mimic, it had been such a terrible experience, I was actually relieved that the movie didn’t become as successful as the Weinsteins wanted. I thought, “If this movie is successful after all that tampering, I’m going to always second guess my instincts.”

DAY: Sunny was lambasted when we first came out. Ten seasons into the show, we’ve never been on the cover of, say, Entertainment Weekly. Sunny has always been under that radar. We haven’t really been acknowledged at the Emmys [the show has received two nominations for stunt coordination]. But if I were embarrassed by the show and we were on the cover of a magazine, you’re right, it would feel dreadful. On one hand, flying below that radar is a blessing, because it didn’t burn our audience out. But on the other hand, you can’t help but have this sort of fear of the legacy, 30, 40 years after the show is done, people looking back and saying, “Well, it wasn’t an Emmy Award-winning show.”

DEL TORO: The only thing you can do as an artist is to come to the world, see what no one is doing, and leave behind one or two things that wouldn’t have happened without you. Nobody would have done Sunny if you guys didn’t do Sunny.

DAY: That’s all we can do. I have to bring myself to whatever I do—I only have me to give.

GUILLERMO DEL TORO IS THE DIRECTOR OF CRONOS, PAN’S LABYRINTH, PACIFIC RIM, AND CRIMSON PEAK, DUE OUT IN 2015.