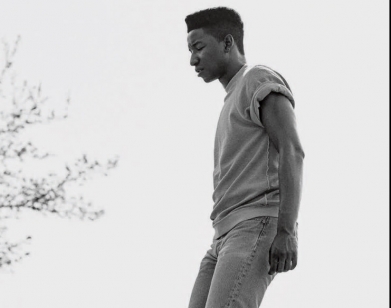

Bill Skarsgård

Of the eight Skarsgård siblings, four of them—Valter, Bill, Gustaf and Alexander—are professional actors, each blessed with the good looks and distinctly rakish swagger of their father, Stellan. So the odds of 26-year-old Bill finding his footing in the industry weren’t exactly stacked against him. More unexpected is the path he’s chosen: neither through the mainstream (such as Alexander, a leading man since his star turn on HBO’s True Blood) nor through auteur-driven projects (such as Stellan, who has appeared in six films by the Danish provocateur Lars von Trier), but rather through a series of unexpected, résumé-confounding detours. Take his biggest American role to date, as Pennywise, the demonic child-eating clown, in the upcoming remake of It, out thisSeptember. As the blood-curdling creature originally played by Tim Curry in the 1990 miniseries of the same name, Skarsgård spends the entire film hidden beneath layers of garish and grotesque makeup—a daring choice for any young actor with matinee idol features.

But Skarsgård has been in the business long enough to know what he’s doing. He spent much of his youth traveling the world with his father, from film set to film set, and his first role came at the age of 9, as the younger brother to Alexander’s character in the Swedish thriller White Water Fury (2000). After being cast in a handful of roles, both big and small, back home—including an award-winning turn as a young man with Asperger’s syndrome in Simple Simon (2010)—his first major appearance on Stateside screens was in the Netflix fantasy series Hemlock Grove. This July, he will begin his play for international stardom alongside Charlize Theron and James McAvoy in Atomic Blonde, a high-octane spy thriller set in a simmering East Berlin. After that, he’ll appear in Assassination Nation, alongside cool-kids Hari Nef and Suki Waterhouse.

But first: breakfast. Over a meal at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, Skarsgård submits to some words of wisdom—and a little gentle bullying—from his older brother Alexander.

ALEXANDER SKARSGÅRD: Did you take out the trash this morning?

BILL SKARSGÅRD: No. Why?

ALEXANDER: Well, as your older brother, I think I should make sure you do that. Routines, or lack thereof, are a pretty good way to get to know someone. So what have you done today? What time did you wake up?

BILL: You were at my house last night.

ALEXANDER: But I tapped out early, because I’m a responsible journalist.

BILL: But being the gracious host that I am, I had to entertain my houseguests. People left around 1 a.m. and I went to bed, so it wasn’t super-late by my standards. I woke up around 10. I had a cup of coffee; that’s the first thing I do in the morning.

ALEXANDER: How do you take it?

BILL: Black.

ALEXANDER: Like your soul?

BILL: Like my soul. [laughs] And then I’ve been doing some really uneventful things. I worked on an audition that I have tomorrow and answered some e-mails, and now I’m here for this interview.

ALEXANDER: I suddenly feel like maybe it was a mistake, as a journalist, to fraternize the night before with the person I’m going to interview.

BILL: Everything that happened last night was on the record—is that what you’re saying? Did you take notes?

ALEXANDER: It was officially off the record, but as a serious journalist, I feel like maybe I shouldn’t have done that.

BILL: Well, that’s on you.

ALEXANDER: It is on me. But let’s move on. You said 10 a.m. is not particularly late for you. It sounds pretty late to me. It’s a Tuesday—shit, I even got that wrong. It’s a Monday.

BILL: Between 9 a.m. and 10 a.m. is usually when I get up. I’ve always been a night person. There’s a sense of virtue attached to getting up in the morning and doing things and starting the day, and I always felt bad for not being that person. But as I’ve gotten a bit older, now I’m completely okay with it. That’s just who I am.

ALEXANDER: Because you feel like you get a lot of shit done at night when other people are sleeping?

BILL: Yeah, or I just don’t like mornings. The day feels way too long for me.

ALEXANDER: Do you also feel that life is too long? Do you wish that life were a bit shorter?

BILL: Just the day.

ALEXANDER: What would be ideal for you, a four-hour day? [laughs]

BILL: Stockholm is a good place for it, in the winter.

ALEXANDER: What do you miss about Sweden, other than friends and family and all that? Is there anything specific that you miss when you’re abroad?

BILL: I miss being in my home country; here, I’m always a foreigner. America is, of course, built of people who are not from here. But going home, even just landing at Arlanda, the Stockholm airport, I think, “This is where I’m from. These people are my people.”

ALEXANDER: Does it make you even more proud of Sweden because you have that distance?

BILL: It’s not about being proud of Sweden; it’s just a sense of belonging. Even if you’ve lived in a place for a long time, those first formative years are going to be a part of you forever, and it’s something you can’t replace.

ALEXANDER: Why don’t you have a home?

BILL: I think it’s a commitment issue for me. I have a hard time committing to stuff.

ALEXANDER: What’s wrong with us? I’m also homeless. Maybe it’s a fear of missing out. Like, if I commit to one city and get a place there, then maybe there is something else out there. But wouldn’t it be nice to have somewhere where you can at least drop your bag and unpack?

BILL: 100 percent. I’ve been living like this for the past five or six years, so I’m looking for an apartment in Stockholm. Just like a two-bedroom thing. Every apartment I look at is so nice and tastefully renovated.

ALEXANDER: Great furniture and beautifully done, but they all look identical. I think that kind of sums up the Swedish mentality in a way. It’s all beautiful midcentury modern furniture, and they all have that Moroccan rug. You won’t find originality. Swedes are very safe that way. So, what’s your first memory from a film set other than with Dad when you were a kid?

BILL: Well, my first film was with you.

ALEXANDER: Oh, yeah. I didn’t want to say it, but I got you into this business. I can take you out of it. [laughs]

BILL: I would never have been here if it wasn’t for the role of Klasse in White Water Fury. I was the only kid on set, and I remember I got upset for some reason. Do you remember the story? I ran away from set or something?

ALEXANDER: Oh, I remember what it was. The fruit basket in your trailer wasn’t fresh enough. And they got Evian instead of Perrier, so you stormed off and called your agent.

BILL: [laughs] At 9 years old.

ALEXANDER: You called your agent-slash-kindergarten teacher. I don’t remember you being upset, but I do have a very vivid memory where you wrapped early one day, and they took you back to the hotel, and I had another scene. When I got back, you were just standing outside in the parking lot, waiting for me, and it broke my heart. It was just the two of us. We obviously come from a big family back in Stockholm. I never felt needed. It was always chaos with Mom, Dad, uncles, you know, we all lived in the same building. Dinner parties with 25 people every night. And for the first time, you and I went away together, and suddenly I wasn’t just a big brother. I felt paternal. You were just standing in the parking lot waiting for your big brother to come home, because you didn’t know anyone and you didn’t know what to do. If I ever need a little sense memory for a scene, that vision of coming around the corner and seeing you standing there, this little boy in this massive parking lot, is really beautiful and heartbreaking. It was the first time I ever felt needed.

BILL: That’s a lovely story.

ALEXANDER: We come from a family of musicians, artists, authors, creative people, and the only exception is our mom and one of our brothers—they’re doctors. How often do you brag about them at dinner parties?

BILL: There’s definitely a sense of embarrassment about what it is artists really do, at least for me in terms of acting. We have a mom and a brother who literally save lives.

ALEXANDER: He works at an ICU so he, on a daily basis, saves lives. Do you have a sense of guilt because he works his ass off and makes less money than you?

BILL: Yeah, of course. It’s not fair. I’m constantly embarrassed at the level of attention actors get and the level of money that we get. It’s completely disproportionate. I think you have to feel guilty about it. I think it makes you a better person to keep reminding yourself.

ALEXANDER: Your becoming an actor—was that the path of least resistance or was it a calling?

BILL: All thanks to you for blessing me with the part of Klasse in White Water Fury.

ALEXANDER: You’re welcome. You might want to remind yourself of that more often, but I do appreciate it.

BILL: I started acting when I was 9. I did smaller parts here and there as a kid, and then as I grew older I started resisting it, because I didn’t like the idea of being, at the time, number four of the Skarsgård actors—Dad, you, and our brother Gustaf. So in high school I majored in science and was like, “Maybe I’ll do something rebellious and become a doctor.” [laughs]

ALEXANDER: Did you seriously entertain that idea?

BILL: I don’t think I would ever be a doctor, but the reason I majored in science was because you could become a civil engineer, you could become a biologist, you could become a computer scientist—that was the point of it. I had no idea what I wanted to do. In my last two years of high school—because they would still reach out to me for auditions and I would read scripts—there happened to be these few scripts that I really responded to. One in particular that I read, I was like, “Oh, this is a real character. This is amazing.” I was like, “I really, really want to do this.” It was Hannes Holm’s film, and I saw him at a premiere—I was, like, 19 at the time, I had probably been to three or four auditions, but I wasn’t cast or anything—and I went up to him and was like, “I don’t know what I need to do, but I need to be in your film.” Eventually, I landed the job, and that was something that I felt transcended whatever other people would think of me.

ALEXANDER: Do you believe you’re a good actor? Do you think you deserve to be here because of your talent?

BILL: 100 percent.

ALEXANDER: Do you ever feel like a shit actor?

BILL: 100 percent. I feel like I’m the best actor on the planet and I also feel like I’m a fraud.

ALEXANDER: Simultaneously, or does it fluctuate?

BILL: They’re kind of simultaneous. I think hubris comes from insecurity. Confidence comes in a more rooted sense; part of being confident is being able to say, “I can be really shitty,” and to accept that. But also not to crumble under it.

ALEXANDER: So, the official It trailer has been viewed over 197 million times. It set a record for the most online views in a single day, when it launched. Why? Do we just fear clowns that much?

BILL: I think it’s huge for an older generation. Do you remember the original?

ALEXANDER: I never saw the original.

BILL: But did people talk about it in school?

ALEXANDER: Yeah.

BILL: I remember It being the scariest thing that existed for a kid. There were other horror films, like Friday the 13th or Halloween, but this was the really scary one because it was children and a clown. So many people go, “That film really destroyed my childhood,” or, “I hated clowns after that.” Hopefully, there will be a lot of 10-year-olds who will be traumatized forever based on my performance. [laughs]

ALEXANDER: Is it R-rated?

BILL: It probably will be, yeah.

ALEXANDER: So those 10-year-old kids won’t be able to see it then.

BILL: Well, no, but—

ALEXANDER: They’ll still be traumatized by the poster.

BILL: But not even that. The movies that they’re not allowed to see are the movies that they’re going to really want to see.

ALEXANDER: Does it feel good knowing that kids around the world for decades to come will have nightmares about you?

BILL: It’s a really weird thing to go, “If I succeed at doing what I’m trying to do with this character, I’ll traumatize kids.” On set, I wasn’t very friendly or goofy. I tried to maintain some sort of weirdness about the character, at least when I was in all the makeup. At one point, they set up this entire scene, and these kids come in, and none of them have seen me yet. Their parents have brought them in, these little extras, right? And then I come out as Pennywise, and these kids—young, normal kids—I saw the reaction that they had. Some of them were really intrigued, but some couldn’t look at me, and some were shaking. This one kid started crying. He started to cry and the director yelled, “Action!” And when they say “action,” I am completely in character. So some of these kids got terrified and started to cry in the middle of the take, and then I realized, “Holy shit. What am I doing? What is this? This is horrible.”

ALEXANDER: Was this your first interaction with a child where you realized how terrifying it would be for them?

BILL: Yeah. But then we cut, and obviously I was all, “Hey, I’m sorry. This is pretend.” [laughs]

ALEXANDER: Last question: Have you called Mom?

BILL: Um, I haven’t called her today, no.

ALEXANDER: No? Call Mom.

ALEXANDER SKARSGÅRD, WHO RECENTLY STARRED IN THE HBO SERIES BIG LITTLE LIES, WILL NEXT APPEAR IN DUNCAN JONES’S MUTE AND JEREMY SAULNIER’S HOLD THE DARK.

For more from our “Youth in Revolt” portfolio, click here.