Birth Cycle

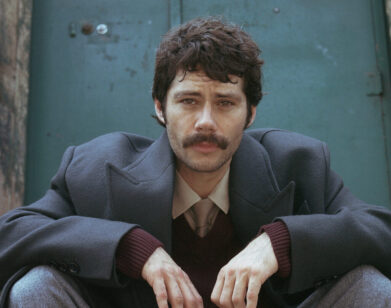

ABOVE: ONDINA QUADRI IN CARLO LAVAGNA’S ARIANNA.

Carlo Lavagna’s debut feature, Arianna, opens with a cryptic message from our titular protagonist: “I was born twice. Actually, three times.” We meet our heroine (played by the ethereal Ondina Quadri, whose face evokes the classicism of a Hellenic bust) at age 19 in a state of great unease and insecurity. Despite regular check-ins with her father (a doctor), visits to her gynecologist (a family friend), and hormone therapy, she still has yet to develop breasts and get her period. Over the course of a summer at her parents’ idyllic lake house in the bucolic Italian countryside, she embarks on an investigation into her medical past, and discovers that she was born with XY chromosomes and ambiguous genitalia, and her parents reassigned her, through surgery at age 3, to a female gender identity.

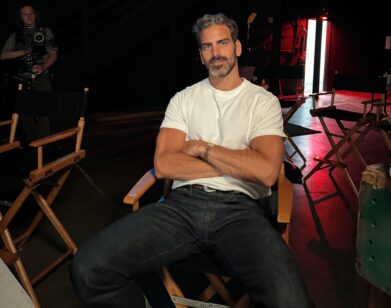

For over a decade, Lavagna has worked on creating a film that describes the intersex experience. Arianna, with its lyrical, lush visuals, is a moving tone poem of coming of age that eschews clichés for a frank depiction of family dynamics, adolescent sexuality, and emerging self-awareness. Arianna premiered last year at the Venice Film Festival, and recently screened at the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Open Roads: New Italian Cinema program. Interview met up with Lavagna and his co-writer, Chiara Barzini, earlier this week in New York.

COLLEEN KELSEY: You mentioned that you both lived in New York before, but how did you two originally meet?

CHIARA BARZINI: We were boyfriend and girlfriend. [chuckles] I was already living here and then we met in Rome. He was living in Rome. Then we decided to make it happen in Williamsburg. This was 2003, I think, and Carlo was already doing research on intersexual people. It was easier to find people who would be willing to talk about that in New York at that time, rather than in Italy. So he did a lot of research, meeting people from intersex communities and interviewing them, and we started a documentary that was the foundation for what ended up being the film.

KELSEY: What made you especially interested in that subject?

CARLO LAVAGNA: Originally, it was a set of dreams I had. When I was a little kid, nine or 10 years old, I would dream of being a woman. They were quite recurrent dreams. You start to wonder about your position in the world, you think it maybe has some sort of erotic aspect to it. After that was philosophy. I started to read books on the subject. It was interesting, because it’s a place where nothing is clear, so, in a sense, it was something that I could relate to and connect to. Then I came here and I started to research. We also went down to D.C. We met some people. They opened their lives up. We started to shoot a documentary that we never edited, but we have some of the material. Then I decided, okay, it would be nice to go back to Italy and make a film there, taking all of these experiences, my personal experiences, plus the people we met, and make a film. So we went back and we started to write.

BARZINI: There was a lot of collecting information. Especially the idea which then ended up being the pillar of the film, the intervention: Doctors intervening, and what does that mean, physically and neurologically. I think America was further ahead than Europe in talking about these things. The idea that you’re essentially denying someone of their physical pleasure, for example, is something that’s starting to get addressed. I think that’s something that definitely struck a chord in Carlo.

LAVAGNA: When we went back to Italy, I started to research and nothing existed. It took a while before a small association popped up on the Internet. I met the girl who founded that, and her name was Arianna. Then she passed away. The story’s not inspired by her story, but she was really helpful in reading the script and making sure that things weren’t too far out in terms of the psychology of the characters. Since then, we’ve met a lot of other people. Now that the film is out, the people come to us. Intersex people came, some very happy and some disappointed. Although, the film is not a social film, say, like, about the surgery. Not at all!

BARZINI: No, but it shows you that even today it’s still controversial subject matter. Even the people from the intersex community have different perspectives on it.

KELSEY: So when did you decide that, rather than this being a documentary, it would work better as a narrative feature?

LAVAGNA: Actually, we tried to make this documentary. We tried to pitch it to televisions and involve other people but it didn’t work out.

BARZINI: Carlo’s documentaries were always really visual, more cinematic than just straight up documentation. So it was definitely already in the cards I think.

LAVAGNA: Then I said, “Okay, let’s do it!”

KELSEY: Well, it’s been a long time coming since you’ve both been working on this idea. You did a lot of this research in the U.S., so when did you think that it would be good to locate the film in Italy?

LAVAGNA: I wanted to do my first film in Italy. I wanted to go back to where I was from. And also because, you know, it’s nice to make something that it’s a little bit more edgy in the theater. To shoot the film, eventually we ended up choosing a place where I’d grown up, sort of where my mom’s from. It’s between Tuscany and northern Lazio, a place I had spent all my summers. Not very known and, so, a place where you can set up, a discovery.

BARZINI: And a sense of mystery.

KELSEY: The landscape is so lush and beautiful and almost ethereal. This is just my interpretation, but it’s the place where she goes back to her true nature and who she is.

BARZINI: Yeah. People have been thinking about that. The film parallels this mysterious nature that you always feel like there’s something hidden behind every corner, and her own sort of self-discovery and her own nature. I think definitely, thematically, they’re intertwined. But that area is so special…that whole part of Italy. It’s kind of semi-abandoned. Tourists don’t really go there, and you have some of the most incredible Etruscan ruins.

KELSEY: How did you find you lead actress? She’s a non-professional, correct?

LAVAGNA: It took a while. I had found a girl who was the daughter of a famous actress and we worked together, and then the film exploded, so, by the time we were able to put together again the funds, she was too old, and we couldn’t use her. Then, one day, I was working with a casting director and he said, “Carlo, you’re not deciding anything. There’s the daughter of a friend of mine, I think she would be perfect. She’s not an actress, but you’ll like her.” So I was like, “Okay, bring her over.” I was really not sure about it. She came and it was Ondina. She looked perfect. But she never acted. She’d never done a film so we had to mutually trust each other. [chuckles] Then we spent really a lot of time together working on the character.

BARZINI: What was really cool when they were shooting was, everyone was staying in the house where they were shooting. Ondina actually slept in Arianna’s bedroom. She got in the role that way.

LAVAGNA: She’s very masculine, you know. It’s incredible how, working on the character, she took the research that Arianna was doing, looking for her femininity, her feminine side, and she became more and more feminine. At the end she was incredibly feminine, and it was like, wow! That was an interesting process that she did.

KELSEY: At the beginning, as a viewer, you’re given the information about these multiple “births” that she has. I figured out her situation pretty quickly—maybe within the first half of the movie. But it’s interesting to see the gap between how the viewer views her discovery process versus how she’s discovering it herself.

LAVAGNA: I think that was the point of the film. To me, it would’ve been a little weird to make a thriller out of that topic. To give that information at the beginning, it helps. You know, but you still want to find out about what’s going on. Then you pay more attention to the nuances.

KELSEY: Well, it even makes those moments of her experimentation with her sexuality even more poignant, because you can feel how painful it is for her to have the confusion, or to not understand why she’s not progressed as much as her cousin.

LAVAGNA: Exactly.

BARZINI: One thing Carlo was really adamant about was that, from doing all those interviews, he said, “These people…it’s never out of the blue that they’re like, ‘Oh my god, you know, I was a boy!'” There’s some part of them that’s just completely buried in their subconscious that already knows, and just instinctively knows, but just hasn’t rationalized it yet. I think Carlo was really strongly pushing this idea of something that’s right beneath the surface.

KELSEY: Obviously there were elements of these real life interviews that you did woven into her character. Were most of the experiences that she has based on people’s true life experiences?

LAVAGNA: You want to be accurate, but at a certain point you have to decide to take a path and even if it’s not completely 100 percent believable or real, it doesn’t matter. You’re making a fictional film. To me, it’s a thematic film, so I wanted to have certain things that happened to these people and describe them. Like, the guy she makes love to the first time, he appears like that. It’s not explained. She says, “He’s someone I like,” but it’s not important. When you’re writing these things you need to be more clear, so we had a scene that we cut out in the beginning so you know that they’re friends in school. It makes it a little too written. Because it’s a thematic film, you say, “Okay, at one point, she will have to make love. Let’s make it now.” It’s a decision you make.

ARIANNA WILL BE DISTRIBUTED BY UNCORK’D ENTERTAINMENT.