Power to the People

Joe Mimran

Canada has never been known for producing titans of the global fashion industry—with one notable exception. In 1985, Joe Mimran, who was born in Casablanca but moved to Toronto at age 5, created Club Monaco, a fashion brand and chain of stores that presented an urban uniform built on casual minimalism. By the time Mimran sold Club Monaco to Ralph Lauren in 1999 for a reported $52.5 million, he had expanded not just across Canada, but internationally, having opened stores in the U.S. and abroad. When Mimran built Club Monaco, he was appealing to our brains. “I’ve become known for black-and-white because that was my palette at Club Monaco for 15 years or longer,” the 59-year-old father of four says from his sleek white offices in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood. “I collected black-and-white photography and I only wore black-and-white; my house was all black-and-white and neutrals.” But with his more recent endeavor, Joe Fresh, Mimran is shooting for something more visceral.

Joe Fresh launched in 2006 at the behest of Canada’s supermarket giant Loblaws, which was looking to sell apparel in its grocery megastores across the country. Mimran was intrigued, but didn’t want to produce the cheap, characterless slurry that overflows from the shelves at Walmart and Kmart. “Nobody was approaching it from a branded perspective,” he says. His solution was to design a playfully Technicolor but chic wardrobe—from classic crewneck tees to maxi skirts to denim trench coats—that could be sold at very low prices. “That’s where all of these clean colors came out of, this desire for the product to be tasty,” he says.

As Joe Fresh began to grow, Mimran made a crucial observation: “The It gals that are buying Prada and Vuitton were coming in and secretly shopping Joe Fresh,” he recalls. Mimran believed the label could stand on its own as a retail brand, and he looked to extend it beyond Canadian borders. As he’d done with Club Monaco in 1995, Mimram planted a firm foot in New York City, where in early 2012 he established a Joe Fresh flagship store on Fifth Avenue, just blocks from Japanese giant Uniqlo, which has become a behemoth trafficking in affordable clothes in candy colors. “I think Uniqlo is definitely competition, but you never get knocked out of the box because of your competitor in fashion,” says Mimran, whose interest in contemporary art helped usher in his brighter palette (painter Alex Katz is a favorite). “You go to Topshop, you go to H&M. Would you go exclusively to one of those stores? No way. It’s such a fragmented industry. Nobody has 5 percent market share. There’s always room for good competition.”

For Mimran, the six Joe Fresh stores in New York and New Jersey are merely a beachhead, but it isn’t all about market saturation. “For me, the thrill is really in developing a brand that has integrity,” he says. “Why does price automatically put you into the category of copier? Why can’t I be as creative? Being unique doesn’t have to be expensive.”

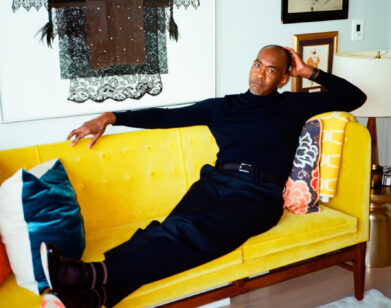

Oskar Metsavaht

Oskar Metsavaht may well be one of the most learned men in fashion. Certainly he’s one of the only designers to hold a doctorate in medicine. An orthopedic physician by training, the 51-year-old Metsavaht is also the founder and creative director of Osklen, the Brazilian apparel company that is looking to assert itself as the nation’s first global fashion brand. Currently selling in 15 countries, with 63 stores in Brazil, 9 more outside of those borders, and with lofty investors circling like sharks, it looks as though Osklen is well on its way. “Clothing is to protect from cold, from rain, from heat, from sun,” says the chiseled Metsavaht, who calls the Rio de Janeiro neighborhood of Ipanema his home. “Also, physicians learn to observe details about human behavior. Through fashion, the human body interfaces with the environment. Who better to understand this relationship?”

The genesis of Osklen has a direct connection to the good doctor’s medical experience. Finding the available winter gear lacking, Metsavaht, an avid outdoorsman, snowboarder, and skier, designed his first weather-resistant jacket for a climb in the Andes in 1986, where he was accompanying a group as the expedition doctor. The garment was so well received that he decided to begin manufacturing it. Over the years, his vision for Osklen has expanded beyond outer-wear to comprise a complete wardrobe for men and women, including footwear and sportswear. Metsavaht’s aesthetic is minimalist, unisex, and functional, inspired by the designs of Oscar Niemeyer and the Bauhaus. “People think, ‘Oh, because Oskar is interested in sports or is a physician, he thinks about comfort first,’” he says. “No, I think aesthetics. I like beauty.”

Metsavaht’s other intention for Osklen is to create a degree of sustainability. Not only are all of his stores in Brazil carbon-neutral, but in 2000 he started the Rio-based Instituto-e, which creates sustainable projects in nearby favelas and poor Amazonian communities, often utilizing their fishing and agricultural technologies in the production of materials for accessories and clothing. It’s a project that has won Metsavaht nods from the World Wildlife Fund and UNESCO. “It’s a culture inside the company. We have to try to be as sustainable as possible without undermining what we need to do economically,” he says. “I don’t see my company or my career as a fashion designer as a green brand. I’m an artist. I’m a creator. It’s an expression of a lifestyle. My lifestyle is not 100 percent sustainable.” The Osklen lifestyle is an enviable one. “I chose an artist’s way of life instead of medicine,” Metsavaht says.

Thierry Gillier

Zadig & Voltaire, the Paris-based casualwear brand founded in 1997 by Thierry Gillier, has some very impressive roots. First, there’s Gillier himself, whose great-grandfather was one of the founders of Lacoste. Then there’s the company’s auspiciously literary name, referencing Zadig, the handsome young Babylonian philosopher and hero of the 1747 novel of the same name, and Voltaire, the writer of the French Enlightenment who authored it. Under that banner, Gillier has created a clothing brand that marries Parisian street style with a tough rock ’n’ roll mentality.

Even when Gillier has talked about his clothes embodying “street fashion at first glance,” there’s still a lot of thought packed into them. “Paris street fashion is something more intellectual,” he says. “In France, it’s more tight, more serious.” Zadig & Voltaire’s remarkable ascent—from a single, humble shop in the Saint-Germain-des-Pres neighborhood, opened in 1997, to almost 200 stores worldwide today—has much to do with Gillier’s intuition in capturing, packaging, and marketing this imprimatur of cool. “There was something new and modern lacking in the French fashion world,” he says. “I had a vision of how to make women desirable and feminine in a more natural, less sophisticated way.” He saw his ideal woman as at once composed and kick-ass. “When a woman wears clothes in a masculine way, she becomes so sexy and she stays young. And I knew exactly how to create that silhouette.” First by word of mouth, and then, over the past few years, with devilishly chic ad campaigns featuring the likes of Mark Ronson (“I met him in a bar in Paris—very handsome, dressed very specifically—he was kind of a new Bowie,”) and downtown New York lioness Erin Wasson (who also designed a Z&V capsule collection for Fall of 2011), Gillier has built a singularly powerful line. “Brands like Chanel left a place for a new, more accessible brand like Zadig,” he says. “Before me, there didn’t exist anything between H&M and these ultraluxe brands, and I invented this new aspect of French fashion.”

In fact, with the growing popularity of Z&V, there has been recent speculation in the French press about private investors buying a stake in the company. That money might prove necessary if Gillier decides he wants Z&V to compete on the megabrand level of brands like Zara, or even GAP in its heyday, a company he greatly admires. “The guy from GAP [Mickey Drexler, the former CEO] was really clever to make clothes for parents, children, every kind of people,” Gillier says. A certified French fashion aristocrat like Gillier holding up GAP as a model is the kind of incongruity that might give Parisian fashion snobs pause, but the notion is one that Voltaire himself might have appreciated. “All styles are good,” Voltaire once wrote, “except the tiresome kind.”

Johan Lindeberg

At the moment, Johan Lindeberg isn’t consumed by fashion. Sitting in the back of the Swedish industry titan’s BLK DNM shop on SoHo’s Lafayette Street, Lindeberg is getting emotional about photography. “I started to shoot like a year ago, and I’ve never felt anything like this before in my life,” says Lindeberg, enthusing behind his signature lengthy beard and Norse eyes. He has just finished shooting singer Lykke Li and actress Stella Schnabel for the BLK DNM blog, and playfully reenacts some of the dramatic camera angles. “It’s very direct somehow. It’s just something I had in my body for so long,” he says about his new passion. “I’m almost crying when I think about it.”

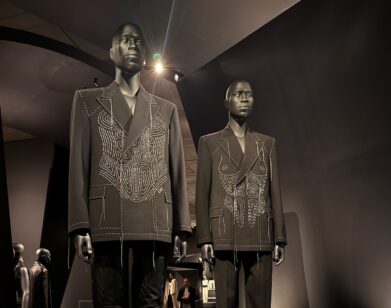

In a larger sense, though, Lindeberg cares desperately about clothes. His 20-year career has seen him help Diesel become a behemoth in the ’90s, first as marketing director, and later as the company’s U.S. CEO. He left to create his eponymous Swedish golf line, J. Lindeberg, which, by the time it was sold in 2007, had xpanded into a global lifestyle brand. He even found the time to help Justin Timberlake become a fashion entrepreneur as the creative director of the pop star’s own clothing label, William Rast. Lindeberg’s latest endeavor is a line of luxury basics for men and women called BLK DNM, marked by a spare aesthetic—tailored, pared-down sweaters, denim, and leather jackets that are numbered, not named, like the tapered “Jeans 8.” “I wanted to create a new brand where I can really express myself,” Lindeberg says. “I think BLK DNM is a manifestation of everything I’ve done in the past somehow, and created in a very personal way.”

Whether taking pictures or reimagining street style, the act of creation for Lindeberg seems to come from the core. “I’ve been living everywhere,” he says. “When I split with my wife in 2010, I went to Montauk. I cried for three days. I walked on the beach. And I decided I was going to be a New Yorker full-time, forever. That’s why I want to create something using energy from downtown.” With BLK DNM stores in NYC and Stockholm, as well as boutiques from Hong Kong to Canada selling their wares, Lindeberg’s very personal vision is proving, once again, universal. So far in the past year the designer has released a fragrance, collaborated on sunglasses with Moscot, and been named by GQ as one of the best new menswear designers. “I would rather be it in women’s fashion, to be quite honest,” he says. “It’s more chal- lenging. But it doesn’t matter. I like to do both.”

For Lindeberg, the accolades and the successes are secondary; toiling away in BLK DNM’s workshop beneath the store, about town at a few of his favorite night clubs, and strolling in the West Village with his 11-year-old daughter Blue are the constant inspirations. “I think I found something,” he says. “I always have pain in my body, all my life, but somehow I feel less pain now than ever. I’m deeper in my intuition, and more pure in my taste than I’ve ever been.”