hype

Kyle Ng of Brain Dead Wants to Connect the World

Kyle Ng in Brain Dead.

Kyle Ng and Ed Davis started Brain Dead about six years ago, making t-shirts. Today the brand is huge, dropping collabs all across the board with The North Face, Converse, The Exorcist, Prince Tennis, and many more. I don’t really know how to describe Brain Dead—by its weird, effervescent designs, its enigmatic logo, its free-spirited, goofy yet savvy approach to retail? Through the brand, you can tune in to the most bizarre YouTube music shows, get to see a forgotten cult horror film, listen to a rare music selection on its monthly NTS radio show, and simultaneously support crucial social causes like Black Lives Matter. As a global creative collective of artists and designers, Brain Dead connects us to the wider world of weirdos through less of a capitalistic model than a cultural one. I spoke with one of Brain Dead’s co-founders, Kyle Ng, to fathom what makes Brain Dead so special, hype, and, well, alive.

———

ALEXANDRE STIPANOVICH: You know, I’m a big Brain Dead fan. I just saw on Instagram that I have been following the brand for 6 years.

KYLE NG: Wow. Man, you’ve been since the beginning.

STIPANOVICH: I’d like to understand the brand more. Let’s talk about your interests as a kid. Where were you born?

NG: I was born in the Bay area near San Francisco. I grew up in the Bay Area, near Berkeley. We were really close to the outdoors and activity, and I was really into that. My dad was really into comic books and movies and science fiction and stuff. So I was really raised around a lot of that kind of world. Also, I grew up skating and hanging out a lot. I was really into music, punk shit, and just all types of subcultures. The Bay Area is just a really big breeding ground for this alternative culture, so it was really built into the DNA of my childhood. I would hang out a lot in Berkeley. There’s a street called Telegraph Avenue, which is a famous, a lot of vintage shops and record shops. It’s the college street next to UC Berkeley. So I’d go there, I’d go to Amoeba Records, do a lot of vintage shopping. There’s a skateboard shop called Five Windows Skateboarding that I’d go to a lot. And then as I got older, I’d go to San Francisco to skate and hang out at this store called Giant Robot, which is an art-focused Asian-inspired store, and my friend Derek was the manager. He was an older guy and I would hang out there almost every day. That was on Haight and Ashbury. I moved to L.A. when I was 17 during my senior year of high school to pursue film stuff, which got me into more fine art and clothing.

STIPANOVICH: Did you explore all this by yourself?

NG: I have a sister, but she wasn’t really into that stuff. I was really into skating and you meet friends through skating, but weirdly enough, when I was a kid, all the skateboarders, we grew up in the Tony Hawk era. Everyone played Tony Hawk—we’d do a game and learn how to skateboard, but all my friends before were jocks. They were into all kind of sports, and then they started partying a lot. When I got into the punk shit, I was still skateboarding, but no one else was doing that. So I was an outcast at my school. No one really skated with me in high school. I’d just do it by myself. It wasn’t until later, when I went to a film program in L.A., did I meet some people from the Bay Area that I really related to. There was this one punk girl named Lisa Winters that I was in gym class with, and she was the only kind of crusty-looking punk girl. She told me that her dad and her build BattleBots, for that TV show BattleBots where these robots fight each other. It’s still on. She was just like, “Hey, you should come and hang out with us one day.” So I started hanging out with them a lot. That was a big tradition in high school. All of us would get together, just nerd out on stuff and build robots and make little short films and stuff. It was really cool.

STIPANOVICH: You weren’t the teenager looking to blend in. You were exploring everywhere.

NG: Yeah, it was a lot of exploration. I think the thing about it in high school, I mean, it sounds so corny, but I was very jocky when I was in middle school and we were very white upper-class kids growing up. And I didn’t really like it. I think a lot of kids and, at the time, a lot of people, didn’t understand me because I was Chinese and Asian and they just thought I was weird for being Asian. I never felt like I fit in because these guys were living a very vanilla lifestyle. I was growing up with my family in Berkeley, with my grandparents and everything, eating crazier food and they made fun of me for all that stuff, but they were still friends with me. And then at some point when I got into the punk stuff, I was like, “You know what? Kind of fuck these kids. We don’t really have anything in common.” All the people I used to play sports with, some of them got into the music scene with me, but then they were just always getting stoned or partying, so I got over that. I think a lot of my childhood was revolting against what I thought I should be doing. Always kind of pushing my own limits of like, “Hey, why am I doing this? What’s the whole point?” I was always experimenting with this idea of not trying to fit in with these people if I didn’t feel like a hundred percent in it.

STIPANOVICH: How did you get into art?

NG: When I moved to L.A., I didn’t drive. So I would take a bus from my apartment building in Studio City and I’d end up at this comic book shop called Meltdown Comics. And there, I would spend like every day, because I’d have to take a bus back home. So I’d spend seven hours there, hanging out with those guys and learning all about comics and art and sculpture. And there were always guys coming through, like musicians and whatever. I met a lot of the people I knew from there.

Brain Dead pasta.

STIPANOVICH: Then you got into the idea of making clothes.

NG: Exactly. I had really good friends in those scenes where they really taught me a lot. There’s a store, Barracuda, where I would hang out a lot too. One of my best friends, Israel, worked there, but he would explain to me all about fashion and brands. I didn’t really know anything about that. I wasn’t a streetwear kid, I wasn’t trying to buy sneakers like that. I was just really more into the art side. But what I realized, especially with Brain Dead, when I started getting into fashion and menswear and all that, is that I knew I had a really strong sense of lifestyle, of who I am, and my interests and hobbies. What I felt strong about was that that stuff, the brand itself, the clothing I make, was just merchandise for my life.

STIPANOVICH: Who came up with the name Brain Dead?

NG: I actually don’t know who came up with the name. I would like to say [artist] Cali DeWitt helped on the name, but I don’t really know if that was a fact. It just kind of happened. We have no idea. We were trying to think about it, but I don’t think anyone knows. To be honest, the idea of Brain Dead was this concept of “We want to make products, we want to show high-quality curated art shows and really high-concept work and art and movies and music that’s challenging, but also have a dumb name that represents it, a name that presents this lowbrow side of us.” It’s about this idea of having fun with your life, but being educated and having taste.

STIPANOVICH: The name also refers to horror movies—that genre of gory, comedy horror from the early ’90s.

NG: Yeah. I mean, a lot of horror films at the time were so smart and thoughtful and intellectual, but they’re under the guise of pulp movies. They’re hyper-violent, but a lot of these films are really smart. And we don’t ever have to fit in the categories just to look smart or look like we’re really intellectual. We want to be goofy, but smart, and not take ourselves too seriously, but actually do serious things too.

STIPANOVICH: What are your favorite horror movies?

NG: I was really into Troma films like Toxic Avenger, growing up. It was just so over-the-top and crazy. I was really into MondoCon films, like cannibal films and weird, crazy extreme stuff because I was so insane. [Laughs.] Then I got really into Italian horror films, like Dario Argento, Lucio Fulci, Mario Bava.

Brain Dead studios on Fairfax Avenue in Los Angeles.

STIPANOVICH: So good. What about music?

NG: I’m really into all types of stuff. Recently I’ve gotten back into kind of more early ’90s emo stuff like Cap’n Jazz and that era of music. I got really into recently a lot of hardcore stuff and metal stuff. So I’ve been listening to this band Mindforce a lot and metal stuff like that. I’m also listening to a lot of really mellow ambient works, a lot of the records by Music From Memory. And then I love this band Syrinx. I’ve been listening to a lot of that. It’s just really the vibe. Octo, the electronic artist vegans label, I love. I’m all over the place with music.

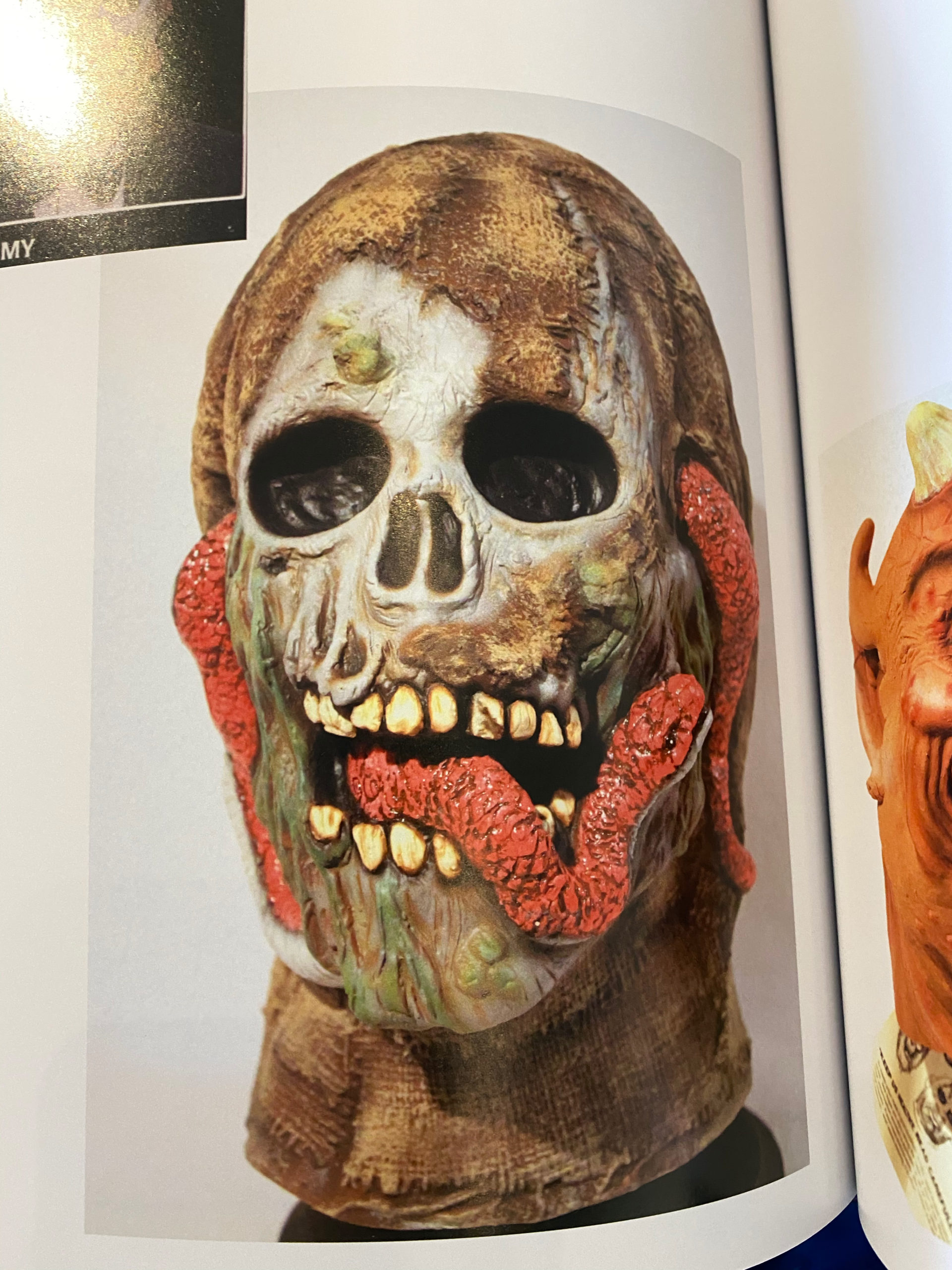

- Some of Ng’s inspirations.

STIPANOVICH: If Brain Dead was a camp retreat, what would the daily routine be like?

NG: I think it’d be all about art and design. Like, in a typical camp, you will have outdoor activities. They’re going to have art classes. You’re going to have crafts. It’s just like the idea of being able to see so many types of lives and seeing so many different communities and trying to understand them. I’m the master of hobbies, man. Every day I go skating, then I go paint-balling every weekend, then I’m playing Magic: The Gathering with some friends, or board games. And then I’m trying to listen to as much music and talk to my friends who are into music, then I’m cooking. I have so many hobbies—that’s what I’m mostly doing. I’m like a professional hobbyist. [Laughs].

STIPANOVICH: I like the idea of connecting different communities, different subcultures.

NG: Exactly. How many people do you see where you’re like, “Okay, I can break down this person immediately,” like, “Oh, they’re into this stuff and they wear this.” Everyone tries to fit into identities.

STIPANOVICH: Yeah. There’s a quote from Ghost in the Shell, the Japanese anime that I love—they say that the effort to remain yourself is what limits you.

NG: That’s genius, man. The great designers or the great people, like Glenn O’Brien—when you see Glenn O’Brien, you don’t look at him as this crazy figure, but he was the most subcultural figure. He was able to transcend into so many cultures and identities, and that’s why he was a genius. The best people were people who balanced all these s who are mavericks in so many genres. But then when it comes to the consumer level, people just want to stay in that little genre. And I think that’s so weird. The people that we all look up to were multidisciplinary, you know?

A Brain Dead candle, modeled after Ng’s dog.

STIPANOVICH: That’s so true. Geniuses often cross the boundaries of genre, while remaining coherent in their own way. What’s your dream collaboration?

NG: Man, there’s so many. I love Dyson a lot, the vacuum company. I think it goes back to the idea of things I use every day. It’s like, “Wow, that really represents my life”—great design, upgrading something that is a pretty mundane object. If it’s a fashion brand, I think it’d be someone like Margiela or MM6 because they were so conceptual and that was so inspiring to me when I got into clothing.

STIPANOVICH: What does Brain Dead have in store for 2021?

NG: We’re working with Phil Tippett, the stop-motion animator guy. We’re trying to make something with him, so that’s going to happen, but we haven’t fully designed anything yet. So that’s really exciting. We’re going to release another climbing shoe, which is a dream, obviously. And we’re releasing a rollerblade, which is insane, with this company Them Skates. That’s really crazy. It’s really the activity things that I’m just like, wow. The more we can go deep into the activity or do it harder and crazier, the more excited I am.