BUTTS

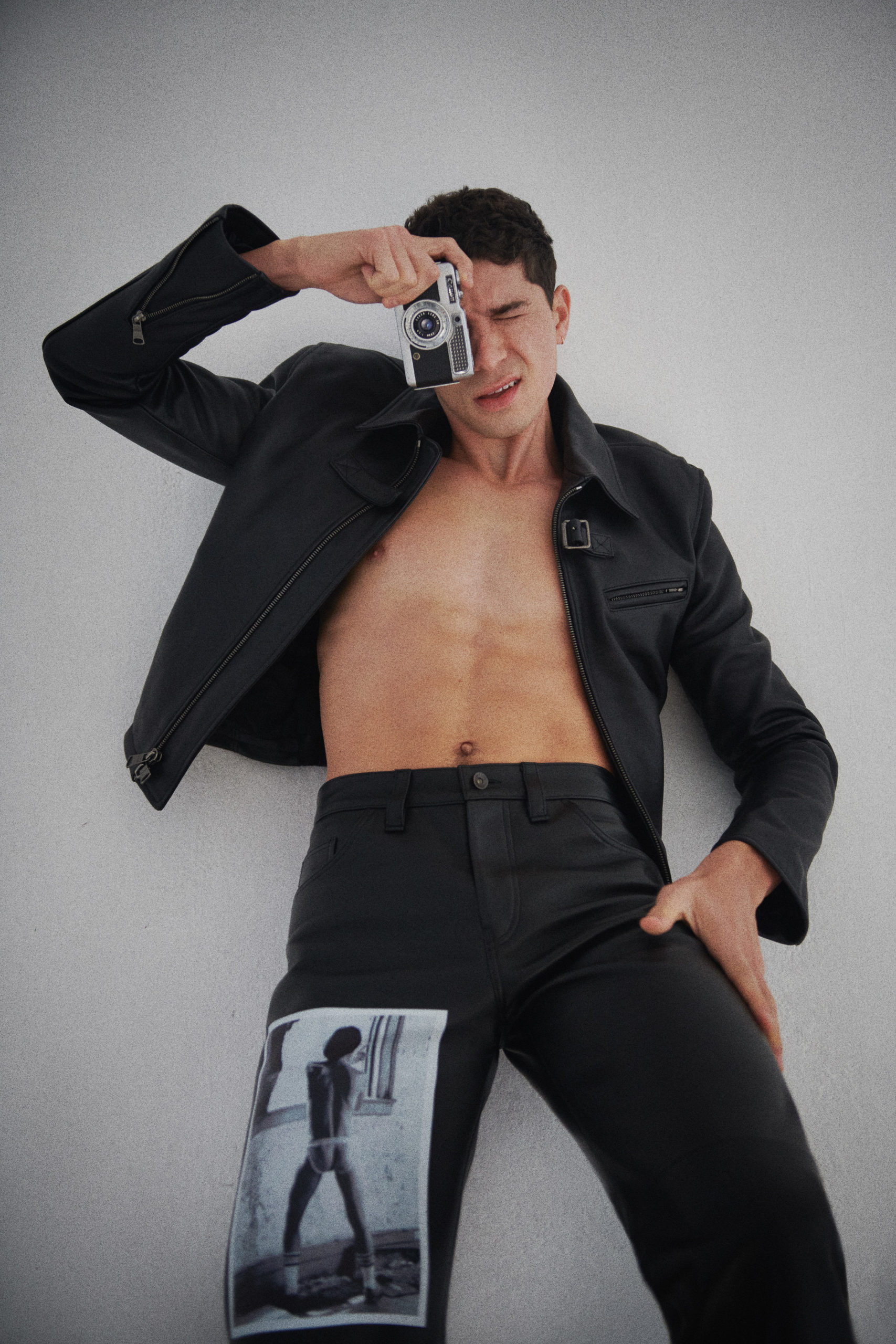

Joseph Altuzarra Wants You to Know Alvin Baltrop

A black-and-white image of an anonymous and firm ass, supported by a jockstrap, might not catch the eye of most art collectors. But Joseph Altuzarra, the French-American designer of his namesake brand and its gender-bending offspring, ALTU, finds beauty and substance in images of half-naked, vulnerable, and hot gay men, particularly those shot by the groundbreaking late photographer Alvin Baltrop. To some, Baltrop is an American icon, known primarily for his photographs of gay men on the Hudson River Piers in the 70s and 80s, just before the AIDs crisis devastated the community. Others, however, will now encounter Baltop’s work plastered loudly across Altuzzara’s new, gender-fluid collection for ALTU, featuring t-shirts and leather pants printed with the photographer’s images. The whole point of the 39-year-old’s ALTU collaborations, her says, is to expose his youthful following to a cohort of artists not of their time, artists, like Baltrop, whose creations might possibly disappear to time, or worse, be forgotten among endless TikTok and Insta scrolls. “I think queer artists have always, for a large part, been either unrecognized or recognized posthumously,” says the designer. “I really feel strongly that those works should be celebrated and should be preserved.” The collaboration comes at a time in the designer’s life when he’s aiming to impress no one and simply satisfy his own beauty cravings, as he told Vogue Runway. One cold and sunny morning last week, Joseph called Interview from his office in downtown New York to discuss the importance of preserving Baltrop’s legacy, the pleasures of displaying erotic art around his house, and the artists he still plans to add to his ever-growing collection.

———

MACIAS: Thank you for making the time. I’m really excited to talk to you about this.

ALTUZARRA: Oh my gosh, of course. I’m excited to talk about it.

MACIAS: Where are you calling me from?

ALTUZARRA: I am in my office in Manhattan. City Hall. Where are you?

MACIAS: I’m on Canal Street in the office, too.

ALTUZARRA: Oh, we’re close.

MACIAS: Super close. I’m really excited that we’re talking about gay art and ALTU. I wanted to start by asking if you describe yourself as a collector of gay art.

ALTUZARRA: I don’t think I’ve ever described myself that way, but I am a collector of queer art. So yes, I guess I would describe myself that way.

MACIAS: How did that journey begin for you?

ALTUZARRA: Yes, I do remember. I think I’ve always been interested in gay iconography from very early on. A Tom of Finland called “Fucker” went up for auction, which I’d always really been into. And my husband and I decided to bid on it and we won the auction. Around that time we were starting to think about collecting a little bit more seriously and what direction we wanted it to take. Generally a lot of what I was liking, certainly, were things that I felt an emotional connection to, that I felt a very personal pull toward. I think I’m a very emotional collector in general, and everything that I was responding to—not everything—but I’d say the common denominator for most of the things that I was responding to was that they were queer artists. So we began really redirecting our collection toward queer art. We now have the Tom of Finland “Fucker.” We have Wolfgang Tillmans. We have two Peter Hujar photographs that are beautiful, one of Ethel Eichelberger, who was a drag queen, and one of David Wojnarowicz. And we have three Mapplethorpe photographs, the more graphic work. From contemporary artists, we have a really beautiful self-portrait from Paul Mpagi Sepuya. I think that’s the direction that we are now taking.

MACIAS: I love that. I’m curious, because we live in a time where people consume so much stuff through Instagram or social media, what role you think gay and queer collectors play in our world.

ALTUZARRA: It’s a really good question. This is actually a nice segue into Alvin Baltrop. I think queer artists have always, for a large part, been either unrecognized or recognized posthumously. I really feel strongly that those works should be celebrated and should be preserved. And also, I think, shown. There is a really big difference between seeing something on Instagram and seeing something in person. I think the physical object is always so much more special, and we’re very lucky to own some of it.

MACIAS: Let’s talk about Alvin’s work. The four images that you actually ended up using on the clothing—what was the process of narrowing it down to those four?

ALTUZARRA: The four images that we used on the clothing?

MACIAS: Yes.

ALTUZARRA: When I started thinking about wanting to do a collaboration, the Alvin Baltrop collection was something that I’ve always been really into since I first learned about it, which was probably 2008. I think I read the same Art Forum article that everyone read that brought him back to light. I had a really long call with the foundation and with a lot of people who either knew him or were specialists in his work. I think one of the things that I really wanted to highlight about Alvin Baltrop’s work was its breadth. I think what people know specifically are the piers, and I think that’s his landmark oeuvre because he was such a documentarian of a particular time in the city. So I think that those images tend to really come to the forefront, as they should. But I also discovered more about his work during the Navy, when he was photographing fellow sailors or fellow soldiers, and then his work also documenting the fringes of the city. I thought that there was this really interesting common thread throughout the collection, which was all about tenderness and love. I think even though we really think of Alvin’s work initially as these quite sexualized images of men cruising on the piers, I think what I was really struck by was that a lot of the images are very tender and very kind. There’s this softness about his gaze, which feels really compassionate and kind. It was a time during which the gay community and gay men had to find love, touch, and tenderness in places that were really on the fringe of the city, and were not really allowed to do that in more—

MACIAS: Public settings.

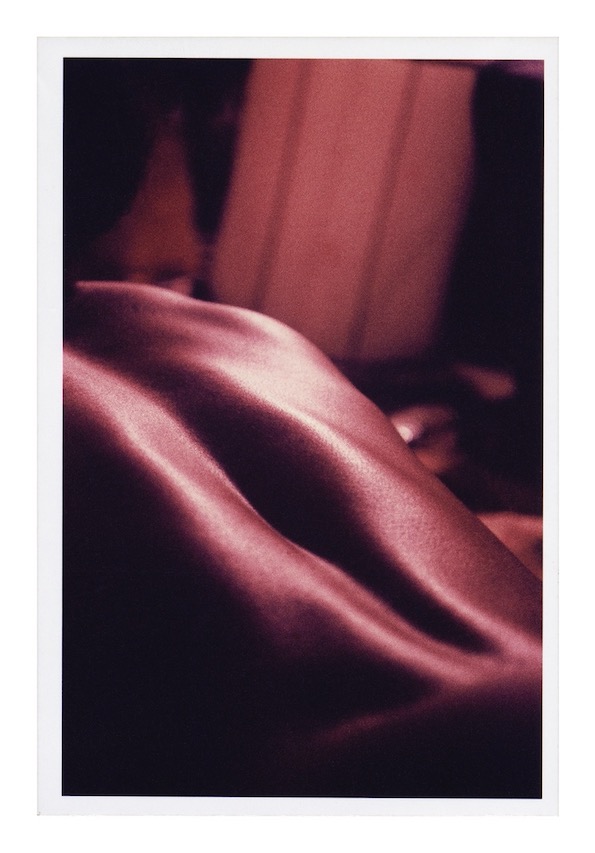

Back, c. 1979, c-print, 6 x 4 in.,© The Alvin Baltrop Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS)vand Galerie Buchholz.

ALTUZARRA: So we ended up picking a couple of images that were really emblematic of the Pier series, that I had either not seen or that I think highlighted that idea of tenderness, but also this very particular lens that he took pictures in. There’s this photo from the series of the Navy, which is the red back. I think the work in the Navy was so sensual, which was interesting, because I think it was probably the beginning of the development of this kind of eye and lens. Then there’s a photo of the motorcycle on the front rack of the truck, which I thought was an interesting reminder that he also photographed a lot of architecture. He photographed spaces, he photographed inanimate objects in ways that both documented and interpreted the change that was going on in the city and in his community.

MACIAS: You touched on that back picture. When I was looking at it, I was like, “It’s so intimate.” But it’s so sensual at the same time. The same could be said about his pictures of the city—there’s intimacy, but also a grunge sensuality to his photographs. Even the photo of the guy with a jock strap standing near a building that’s falling. It doesn’t feel sexual. It feels sad, in a way. Do you have a personal favorite of the images?

ALTUZARRA: That’s my favorite. The jockstrap picture is my favorite. I love it because he looks like a demigod or something. I agree there’s a sort of melancholy, and there’s an almost sad tenderness to the image, but there’s also this feeling of really giving his subjects this nobility or grandeur, which I think was really nice. It never felt grimy. His images are never these grimy dirty feelings, characters, or spaces. They always feel like they’re these Adonises, which I really like.

Big Boy, c. 1979, silver gelatin print, 4 1⁄2 x 6 2⁄3 in., © The Alvin Baltrop Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS) and Galerie Buchholz

MACIAS: Which, in the context of the time period, adds another layer to that subject. This is the first time you’ve done this type of collaboration for ALTU, featuring artists on the clothing. Why did you decide that he was the right person to kick this off with?

ALTUZARRA: Well, in part because I think the mission of ALTU, in some ways, has shifted. Over the years that ALTU has been created, I think we’ve learned more and more about what we want to express and what I want to say. I think a lot of it is what I personally believe in. ALTU is a very personal expression of what I’m interested in and what I like. I think I decided I really wanted ALTU to live in this very gay space and really speak to a very gay audience. I think I have this very passionate love affair with queer art and I wanted to express that through the collection. And with Alvin, there was a real desire to do something with an artist who had been not celebrated, or was underrepresented. When I spoke to the foundation, it was a way for us to start getting involved in the community. Alvin Baltrop in his lifetime was not able to develop all of his negatives, just because he didn’t have the money. So the proceeds for this collection are going toward the digitization and development of thousands of negatives that have never been seen before. That’s something that I really care about personally. I think it’s a super important project and I felt like this would be such a great way of helping fund that project, and also to help talk about Alvin’s work, and how special I think it is.

MACIAS: So were you able to spend any time with the archives?

ALTUZARRA: Not yet. That’s actually in the works, for me to go to spend some time with the archives, but I haven’t been able to do it yet.

MACIAS: That’s exciting. Do you own any of his work yet?

ALTUZARRA: No, but I’m dying to get my hands on something.

MACIAS: Amazing. And so the idea is you’d digitize the negatives and then show them at some point?

ALTUZARRA: I think, obviously, the foundation and his gallery know his work intimately, and know what to do with it much better than I would. I certainly think the idea would be to show them and to make them available to the world, just because I think it’s another layer of discovering who he was.

MACIAS: What can we, a younger generation of queer art lovers, learn from his work?

ALTUZARRA: That’s a really good question. I think what’s so special about his work—and I say this as an almost 40-year-old gay man—is that I think he had a role both as an artist and as a documentarian. There is a sense that our history as a gay community was really either erased or was pushed to the fringes and not explored, not taught, not celebrated. I think, to me, Alvin’s work brings that back to the forefront. He’s able, through his work, to give the community its history back. I feel that way a lot about queer artists today, this sense that we need to make sure that we’re supporting them. It’s really important to support younger artists because I think they’re really vital to continuing to tell the story of our community.

MACIAS: So this doesn’t happen again in the future, where our history gets erased or overlooked. You mentioned earlier that you have some erotic art. Is it on display at your house?

ALTUZARRA: I do.

MACIAS: What are your guest’s reactions when they see all these butts and dicks on your walls?

ALTUZARRA: I would say, generally, shocked acknowledgment. They’re like, “Oh.” I can tell there’s a little eyebrow raise. I think it’s really important. I certainly feel that sexuality is not something that we should be afraid of. I’ve gone into a lot of people’s homes who have a naked woman, a naked lady, in a painting, so I’m like, “Well, this is art.” I think I’m very unapologetic about it and, listen, we have friends who obviously are very supportive and tolerant.

MACIAS: What is one piece of queer art that you’re dying to get your hands on?

ALTUZARRA: Oh my God, there’s a lot.

MACIAS: Does one come to mind?

ALTUZARRA: Well, I’m very obsessed with Salman Toor and his paintings. So that’s one thing. We’ve been chasing a few very specific Wolfgang Tillmans for a while that we’ve never been able to get at auction. Those would be our holy grails.

MACIAS: Have you learned anything about yourself or the brand through working on this project and Alvin’s work? Has anything been revealed to you?

ALTUZARRA: Yes. I think I have learned a lot. One thing I’ve really learned is how central queer art was and is to the aesthetic of both ALTU, but also how I dress and what I like. It is very seminal and has had a lot of sway in the development of my eye, the development of what I like. I think through researching Alvin’s work specifically, but a lot of other queer artists, that’s come into focus for me.

MACIAS: What does the future hold for you and ALTU?

ALTUZARRA: To me, this was just such an exciting and interesting project that I would love to do more of them. We’re continuing to develop the brand, but I think this was such an interesting way of speaking about what ALTU is about, also speaking to our community, and also getting involved as an agent of change,and an agent of discovery. That is something that I would love to continue.

MACIAS: Clothes as a means of discovering art. I love it.

The Piers (exterior with couple having sex), c. 1979, silver gelatin print, 4 5⁄8 x 7 1⁄8 in., © The Alvin Baltrop Trust / Galerie Buchholz.