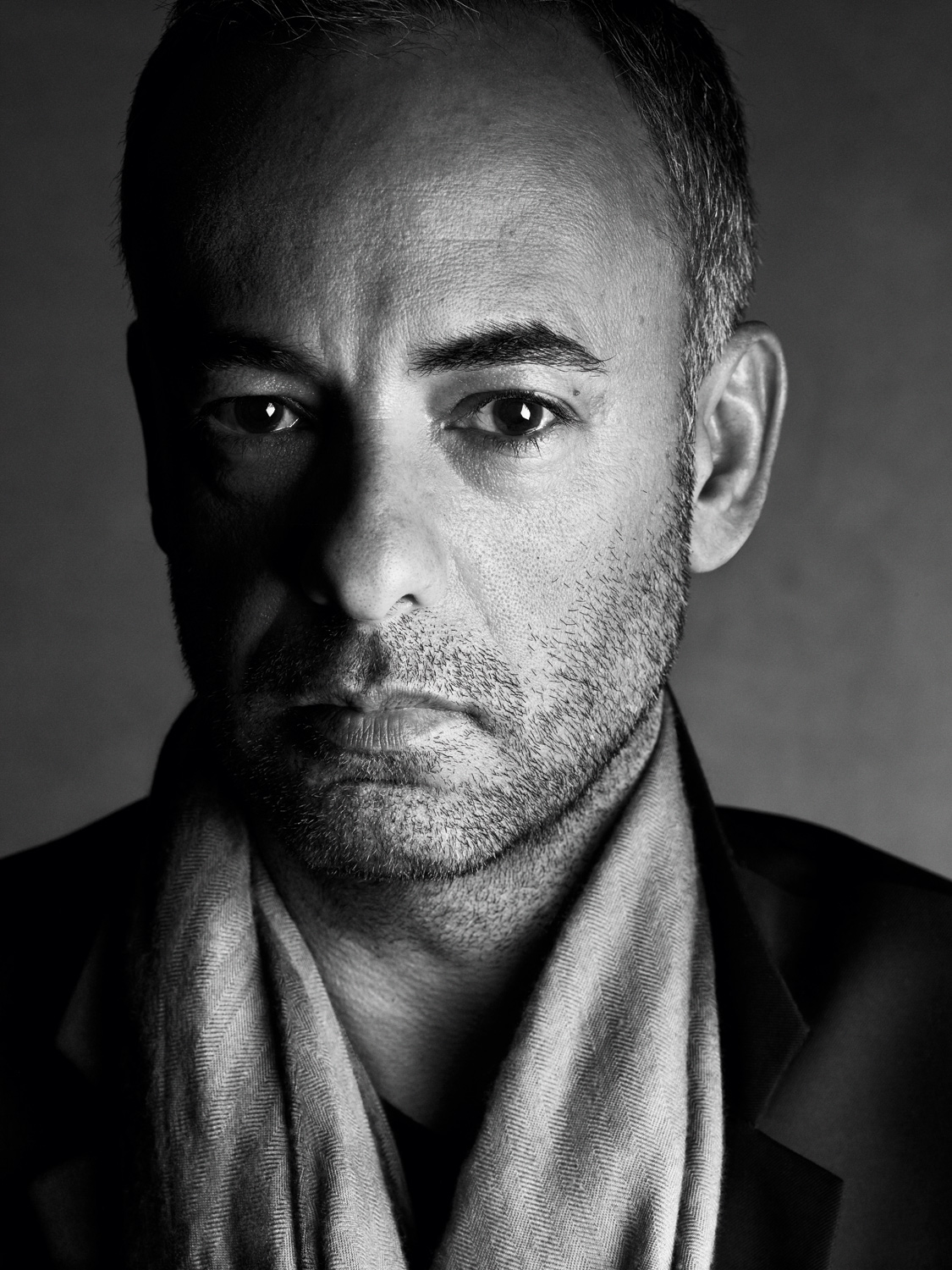

Francisco Costa

Calvin has purity, this simplicity, this Americanism. It speaks to certain kinds of women who are very secure, very modern—they like looking forward.Francisco Costa

Has the Calvin Klein woman suffered a change of mood? Or has she just toughened up? For the last nine years, or 18 seasons, as women’s creative director at Calvin Klein Collection, 47-year-old Francisco Costa has simultaneously managed to preserve one of the most iconic brands in fashion—one that has proven to the world that Americans can be spare, chic, and sexy right alongside their European counterparts—while also creating his own individual sense of feminine style with an emphasis on curving silhouettes and a heightened attention to technological detail. Under Costa’s watch, the Calvin Klein woman has enjoyed the 21st-century with a lightness and a brightness reminiscent of the minimalist luxury that Klein himself helped foster since the brand’s inception in 1968. But Costa is no slave to the past, and it was a bold, unexpected, and noticeably tougher tone with which he launched his defiant Fall 2012 collection, delivering some of the sharpest edges the label’s ever seen while under his direction. (The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo actress Rooney Mara sitting front-row gave some suggestion of where the Brazilian designer’s mind might have been during the research stages.) Black leather was in abundance as were metal belts, knee-high crocodile boots, and leather mesh that gave the effect of chain mail. Costa’s women were shielded and guarded, ready for a fight, but he still managed curves and flaring forms that didn’t mark them as androgynous beings. Costa may like to experiment, but, at heart, he is a lover and admirer of women.

Having grown up in the small town of Guarani, he left his native Brazil in 1985 for New York City with only a few English words in his repertoire and only a hint of the career he was about to embark upon, Costa has active intents beyond fashion in art and design. He recently invited art photographer Ryan McGinley up to the Calvin Klein offices in midtown for a little talk that basically covered it all: love, rebellion, religion, women, becoming his own man, and what he keeps in his refrigerator. The last time Costa saw McGinley was at the photographer’s short-lived Thursday night party at BEast on East Broadway on the Lower East Side, and that’s where the two began.

FRANCISCO COSTA: I remember seeing you at that club night you used to do at BEast. Are you still continuing with that?

RYAN MCGINLEY: No. The club wasn’t successful. I started that night because I thought it would be a way for me to connect with the gay community, because over the years I just never felt like I was all that happy about going out in general. Then a friend said, “We should start our own party.” So I thought about the music and the people I wanted to invite, and in the beginning, it was pretty good. I didn’t create it to promote it. The club kept saying, “You gotta get people here,” and I was like “Man, I have a job. I’m only doing this to get laid!” I just wanted to meet people I had something in common with.

COSTA: Did you find what you liked?

MCGINLEY: No, I didn’t! That’s why I kind of gave it up. I really felt like the night was out of my control-it became Lady Gaga and Beyoncé and just a typical club, and I had no control over it. It was a good lesson for me, and I’m glad I tried it, but I don’t want to go out at all anymore. The problem is that then I get isolated.

COSTA: Yeah, I guess there are not that many places to go out anymore. I remember when I first arrived in New York City in 1985. I was almost 30 years younger than I am now, of course, but there was so much going on. There were all of these underground places in the East Village, which were really cool. And the places were so nonjudgmental. They were just about whatever. There was The World, and Save the Robots, and other places like Area. It was this really wild, interesting mix of people. And there were no labels. It was very free and very cool. But maybe because I’m older now, I don’t go out.

MCGINLEY: When you moved here in ’85, you didn’t speak English. How did you communicate with people when you went to the clubs?

COSTA: I don’t know. [laughs] Language of love!

MCGINLEY: Maybe that worked to your benefit.

COSTA: Totally. Because I was so naïve—really just so young in New York City. I arrived, and two weeks later it was Gay Pride and I had never seen anything like it. I come from a town of 2,000 people, and although I had lived in Rio for about three years prior to coming to the U.S., there was a lot of friction in New York, a lot of volume. It was the era of Reagan, and there was a lot of energy. You just felt like you belonged to some sort of movement bigger than yourself. It didn’t take me long to learn and explore.

MCGINLEY: What was it like in the ’80s? Were you a political person? Did you ever get involved with Act Up?

COSTA: I did in my own way. There would be meetings in the street, and in fact, I paraded with Act Up in Gay Pride a couple of times. I wasn’t terribly political. I just felt that there was so much freedom, so much pride-it all felt very relevant and I needed to be part of it.

MCGINLEY: When you first moved here, who were the people you were hanging out with?

COSTA: I never had that many friends. I was kind of a loner. But I had a few Brazilian friends that I used to see. I started taking classes at FIT at night as a continuing-education student, and I was going to Hunter College in the morning to learn English. So I managed to make a few friends from school, and they were really cool people. They used to perform at Boy Bar. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of that place.

MCGINLEY: My older brother was gay, and I was very involved with him and his boyfriend and all their friends in the city in the ’80s. I’m from across the river in New Jersey, so I used to just come in and hang out at the parade here in town, stuff like that. Did you have a boyfriend in Brazil before you came here?

COSTA: I had one boyfriend, yeah. And before that I had a girlfriend. I didn’t care about my sexuality. I knew I was gay, but I also didn’t—it was whatever it was. I think that was why New York was so liberating for me. It was like, This is it!

MCGINLEY: Did you feel like coming to New York, you could start over with a new identity?

COSTA: No, not a new identity, but an outlet to explore my sexuality, the direction I wanted to take—it wasn’t really premeditated. Nothing was planned. You go on experimenting and touching until you get somewhere and then move on.

MCGINLEY: What were you like in high school?

COSTA: [laughs] Anal. I was so anal! Even before high school, I had a very unorthodox kind of education growing up in this very small town. There were only two schools—the uptown one and the downtown one. I went to the downtown one and it was kind of a state school but with nuns and priests running it. There were a lot of rules. Every morning you had to go and sing the national anthem and raise the flag. I always wanted to be the first in line. We wore uniforms—navy shorts and cropped white shirts—and every week the kid who kept his uniform the cleanest got a red cross on his shirt, which you’d carry with pride the whole week. You were looked at as special. So there was a lot of pressure in that environment. In high school I focused on technical courses. Accounting.

I did other jobs—from walking dogs to cleaning apartments to working at a furniture store . . . I was definitely running for cash.Francisco Costa

MCGINLEY: Accounting?

COSTA: It had nothing to do with me. I don’t even know what one plus one is. I don’t know how I ended up there.

MCGINLEY: Is that what your parents wanted you to do?

COSTA: Yes, because of their business. They were childrenswear manufacturers. Right after high school, I moved to Rio and took classes to become a technician for a manufacturing factory where you had to figure out how to produce 3,000 pairs of jeans. But in Rio, I was by myself, which was very liberating, being so young. I got to do my own thing.

MCGINLEY: Did you go to the beach a lot in Rio?

COSTA: I used to go to the beach at four in the afternoon and stay until seven. It’s like a bar. The beach is where everyone hangs out in the afternoon, just standing around.

MCGINLEY: Just watching each other walking around in their bathing suits.

COSTA: Yeah. It was kind of sexy.

MCGINLEY: What kind of bathing suits did you wear?

COSTA: Speedos.

MCGINLEY: Really?

COSTA: Yeah, of course. The smallest ones possible. [laughs]

MCGINLEY: Would you ever go in the water, or would you just hang out on the beach?

COSTA: I did both. I liked the water a lot. But in Rio, that’s how it is. Everyone just hangs out and smokes pot, and it becomes this whole social thing. I remember the school I went to was a government-sponsored school, but you could only be a part of it if you had a relationship with any manufacturers. My parents had a factory, so I was linked to the textile and fashion industry. There were people from all over the country in that school, so it was very diverse.

MCGINLEY: When you were in Rio, did you know that you wanted to be a designer?

COSTA: I think so. I really had a feeling. Growing up, after school, you had to go and work in the family factory. It’s just what you had to do, so it was very natural. I didn’t know anything else. But I did other things, too. I painted, and I loved building homes—especially for my cats. I was always trying to put things together.

MCGINLEY: It’s funny because the clothes you design are so architectural. I, for example, never built houses as a kid. But that you did that makes sense to me.

COSTA: Yeah, I loved it. I made them very elaborate. I moved to different kinds of materials, from wood to Styrofoam to paper. I landscaped as well.

MCGINLEY: Do you think that growing up surrounded by clothes manufacturing gave you a special advantage as a designer? You understood how things went from point A to point B.

COSTA: It was children’s clothing, so I think you could say yes and no. I wonder if I would have been less organic of a designer without my background. Maybe I would be more academic about designing, more methodical. I want things to be a certain way and I’m very precise, but school itself wasn’t that relevant for me. I always knew what I wanted to do and how I did it was very unorthodox. I didn’t even graduate, per se. I graduated, but they had to give me this award 10 years later in place of graduation. It was just another outlet for me to understand and explore.

MCGINLEY: When you were younger, did your mother pin clothes on you and make clothes for you?

COSTA: Yes, she did. I remember these little overalls, with a very wide strap, square pleat. But I also remember building dolls and dressing them up, too, to play with.

MCGINLEY: Did you have favorite dolls? Were they men or women?

COSTA: Oh, they were all women, of course. No Kens. [laughs] They had dresses. They had all sorts of characters. Some were brides. You know, Brazil is very well-known for its soap operas. So it’s this drama and nightmare, and it has a big impact on culture. I think they had an influence on the characters I made. They weren’t based on them, but they were influenced by them. What did you make when you were a child?

MCGINLEY: I used to draw pictures of girls naked. I have five brothers and two sisters. My mom had seven kids in seven years and then she had me 11 years later. When I was born, my oldest brother was 19 years old. So I was raised by all these teenagers. They ran the whole gamut: the business guy; the cheerleader; the stoner; the punk-rock girl; the gay guy; the weirdo-everyone was so completely different. I grew up in Ramsey, New Jersey, which is 20 minutes over the George Washington Bridge, so I would come to New York all the time. A good number of my siblings lived in the city.

COSTA: How was their relationship with you? Did they know you were gay?

MCGINLEY: I didn’t know I was gay. That’s actually one of my biggest regrets in life. My brother and all of his friends died of AIDS—his boyfriend, everybody. I didn’t realize I was interested in men until I was like 17 years old, and he passed away when I was like 16. It’s definitely made me stronger.

COSTA: Is that why your relationship with your pictures is so youth-driven and character-driven?

MCGINLEY: My mother pointed it out when I first started showing work. She said, “You’re traveling with all these people, and all of them look like your brothers and sisters. Do you see that?” And I was like, “Yeah, I guess so.” It’s just so comfortable to hang out with so many people. But I feel that the adventure in my photos definitely has something to do with when my brother died. It was such a traumatic moment of my life. I just started going wild and I didn’t care. I was like, “I’m going to go crazy and party and do whatever I want to do.” In the beginning, it was insanity going into New York and going to clubs. I started taking photographs toward the end of college. But that sense of rebellion has definitely come to the work-and the idea of having adventures.

COSTA: My mother passed away when I was 21, and we were really close. Something broke off in me, that love you have for your mom, and after that I felt like I had nothing to love. She was someone I really trusted and I didn’t have that anymore so I thought, I really want to go somewhere. It happened that two friends in Rio were going to Disney World!

MCGINLEY: This sounds good already.

COSTA: So I said, “Okay, let’s go to Disney World!” And obviously we were going to stop in New York before we returned to Brazil. And when I came to New York, it was nothing as I imagined. I imagined it to be really polished. By chance I searched for a school and found Hunter College. But I had no money and I had to go back to Brazil to get my visa. So I went home and told my dad I had to go back. He said, “You have no money. How are you going to afford living there?” And I said, “I don’t know. I’ll figure it out.” So he ended up giving me some extra money and I moved back. It all just happened. I felt an urge to come here and I did, and then here we are. Soon after Hunter, I was accepted to classes at FIT.

MCGINLEY: What was that like?

COSTA: It was interesting. My first class was design because, again, I couldn’t speak a word. But I passed it with an A. The whole directive of the class was to identify silhouettes. It was Fashion 101, once a week. So I started going around the city with a camera and taking pictures of all the windows. I created a visual diary of what was happening in fashion, and I started to identify the silhouettes and I was inspired. It was very current, very accurate. It was a continuing-ed night class, but I spent all my time doing research. So that’s how I passed the course. What’s funny is that one day I passed a bulletin board at school that said there was a contest for FIT students to submit portfolios to go work in Italy for the summer. I applied, and they couldn’t find me in the registry because I wasn’t a daytime student. They didn’t think any continuing-ed student would register. So they loved my submission, but I was ineligible. Next year they call me back and say, “The board decided you’re gonna go.” So I did go and ended up winning the contest. It gave me a scholarship to finish school in the daytime.

MCGINLEY: Eventually, after you got out of school, you went to work at a company that made clothes for Bill Blass. Were you supporting yourself solely as a fashion designer from the outset, or did you have to do other side jobs?

COSTA: I did other jobs—from walking dogs to cleaning apartments to working at a furniture store. I worked as a salesman for the furniture store George Smith. I was definitely running for cash, money to go out . . .

MCGINLEY: Were you a good salesman?

COSTA: No, I was terrible. I was so frightened. I’m a very good salesman, actually. I love to be in the showroom showing the clothes off to the customers and what have you. But selling stuff is a whole different thing, especially that furniture. It’s all custom-made, and you choose how much down you want, and how much foam you want, etc. I’m like, Who cares? Actually, I used to run away from buyers. [laughs]

MCGINLEY: I wanted to ask you about the imagery. In high school, I used to have those iconic Calvin Klein ads hanging on my bedroom wall-the pictures of Kate Moss or Marky Mark. And the controversial ads that Steven [Meisel] took. They were amazing. I remember seeing them in Rolling Stone and thinking, “This is so cool. Where can I sign up for this?”

COSTA: Those had an influence on you? I sense that in your work.

MCGINLEY: In terms of advertising, those were the ads that spoke to me the most. What were some of your favorite campaigns over the years?

COSTA: Of Calvin’s? There are so many. But I think Kate’s spirit was probably the most striking. It was so ’90s and gritty.

MCGINLEY: I remember the topless ads of her were so controversial.

COSTA: It just hit all the right dots at exactly the right time, which is amazing. In Brazil, that had a tremendous impact as well. The pictures are quite classic, and they are reserved at the same time.

MCGINLEY: I’m curious what drives someone to be a fashion designer-and why so many gay men do it. I wonder if that has something to do with not fitting in and dreaming of other worlds. Are there any specific qualities that you recognize sharing with other designers?

COSTA: I think we are fascinated with women. And maybe some of that has to do with fantasizing about creating a world. That’s why there are schools of tastes, right? And certain people fit into different tastes. Like Calvin has purity, this simplicity, this Americanism. It speaks to certain kinds of women who are very secure, very modern—they like looking forward. It’s a lifestyle that Calvin has created that is very grounded, chic, and timeless. He just brought that whole world into existence. It’s true, there’s this dream, this ideal woman that you idolize, that you feel is part of your world. But there is also the matter of craft—the knowledge and the interest and the desire to apply those skills. If you think of the iconic women who have influenced designers, they are so important. They give a designer such strength. I want everyone who comes in to buy my clothes to feel a little better. I think being inspired by women is really the number one thing. I could not design for women if the woman was not important.

MCGINLEY: How are you different now than you were, say, five years ago?

COSTA: I’m just generally more comfortable in my own skin. I’ve been here for 10 years, and it is a pretty big job. I don’t know if I realized at first how big a job it was. So five years ago there was much more hesitation—a sense of having to prove something. I feel very comfortable right now, very at ease. I’m not saying that I won’t mutate. I will continue to evolve, but right now I’m very comfortable with things I like and don’t like. When you find that sort of common ground, it’s nice. People have asked me recently how I’m affected by my reviews and, in the corporate world I respect that. I respect anyone who has something to say. But you can’t please everybody.

MCGINLEY: How do you balance the Calvin Klein aesthetic with your own aesthetic? How does that evolution work?

COSTA: Calvin actually once said to me that he never looked back. I think it’s probably the genius about him. I try not to look back. I try not to look in the archives or at stuff I’ve done. I think it’s so much more interesting what’s to come. I never consider myself a minimalist. But another word is reductionist, and that’s something I’m beginning to understand. I will never be Calvin because Calvin is a genius and he did what he did. I’m here now, this is what I can offer, and I have to be extremely honest with what I can do and really genuine and offer that.

MCGINLEY: Those words—reduction and minimalism—mean very different things, but people think they are very similar. But reduction is about reducing, pairing things down, taking away.

COSTA: What bothers me about the term minimalist is that it is so connected with a distinct period. It links me to the past. But I design for today. I’m a book freak. I’m buying five, six, seven books a week. I just want to feed myself. So I start with a lot-millions of pictures, millions of fabrics, millions of colors. Then as I work, it starts to be reduced and I pin the things that are relevant up. So, yes, those words carry a lot of weight and I don’t want them to be misrepresented, but I try not to associate myself with terminology. I want to be free to some extent.

MCGINLEY: I want to talk about horses. I read that your boyfriend owns horses and that you ride. What does horse riding offer for you?

COSTA: I don’t know . . . Horses are very sexy. There’s this tension, right? The horse could just take off, so it’s very important that you lead. How you communicate is very important. For me, psychologically, that’s very interesting. And then just galloping on a horse is fantastic. The last time I rode was in Brazil in this place called Bahia. It’s in the north of Brazil. I rode for six hours. John and I, we just couldn’t stop. We really explored. But John is very serious about horses. He used to ride as a kid, and he used to ride at a stable in New Jersey.

MCGINLEY: He’s from New Jersey?

COSTA: Yeah.

MCGINLEY: That means he and I are instant friends, because, you know, people from New Jersey have an instant connection. What is your home like?

COSTA: My house is very clean.

MCGINLEY: Is it the Calvin aesthetic? Is everything hidden?

COSTA: No, it’s not everything hidden. I think it’s just reduced, edited. My apartment is very edited. It’s very masculine. It’s not sterile. There are a lot of textures.

MCGINLEY: That’s hard for me to envision. It seems to me kind of like Calvin—it’s masculine, it’s clean, it’s bold, but where does the toothbrush go?

COSTA: Well, the toothbrush goes into a cabinet, and the cabinet is flushed into the wall. It’s a cabinet you don’t see. I have a lot of hidden doors in the apartment. [laughs]

MCGINLEY: What’s behind the hidden doors?

COSTA: They are architectural solutions for a small space. It’s not like I’m trying to create something that’s revolutionary, because that exists. I did some interesting shelving. I thickened some of the walls to create passages, to give a sense of the apartment being grounded.

MCGINLEY: Are the washer and dryer easy to find?

COSTA: They’re hidden. [laughs]

MCGINLEY: What’s in your refrigerator?

COSTA: A bottle of Cristal, some Coca-Cola, vitamins, some grapes.

MCGINLEY: Do you drink Coke, Diet Coke, or Coke Zero?

COSTA: Regular Coke.

MCGINLEY: That’s so un-New York of you.

COSTA: I don’t believe in anything diet.

MCGINLEY: If you were somebody else, would you be friends with you?

COSTA: Yes, definitely. Absolutely.

MCGINLEY: If you were to describe yourself to somebody who didn’t know how to find you in a crowd, how would you describe yourself?

COSTA: I don’t know, short, cropped, dark hair, five-foot-seven-inches tall, white shirt, black eyes.

MCGINLEY: You have such a big team at Calvin Klein. How do you maintain your vision? Or just decide to spend time in the studio by yourself?

COSTA: I think the most productive calendar is the weekends and after-hours.

MCGINLEY: At the office?

COSTA: Yes, six o’clock I start. I love silence. I do not work with music. I find it highly distracting.

MCGINLEY: I was shooting photos in the studio last week, and I think especially because I’m shooting nudes that music offers this barrier. It creates a vibe and calms people down. But also when I’m working by myself, editing, I feel like music is so important. I am interested in the idea of working in silence. I said to my friend, “How funny would it be if somebody came in here and we didn’t play music?” There have been certain photographers who never used music. It was completely silent. Whereas I really rely on it.

COSTA: I understand the effect of music. When I listen to music, it just puts me in a different place. But I just have to listen to my own rhythm.

MCGINLEY: Do you go to church?

COSTA: I do go to church once in a while. On Mondays, I go to a church on 37th Street between Broadway and Seventh Avenue.

MCGINLEY: What are your beliefs?

COSTA: I grew up in a very Catholic environment. I’m free-form. I believe there is something there and something you have to respect, but I also believe in nature. I believe in spirituality in nature and the balance of the environment and to respect it by the things that you do. I’d just like to be good, you know? Not just good, but to be very straightforward.

MCGINLEY: Do you believe in karma?

COSTA: I do. But I also think you can change that. I believe you can transcend it or just slightly shape it. It’s hard work. I think it’s really hard work, but that’s why I exercise a lot. I pray, too. That’s my motivation to exercise. There’s a sense of security that comes with it. You feel more attuned.

MCGINLEY: Is there any advice you can give a young designer just starting out?

COSTA: I think you just have to work, man. Work is so dignifying. That’s the advice, just keep working.

MCGINLEY: I think that, too. It’s not necessarily that I’m the best out there, but I do feel like I work the hardest.

COSTA: I wouldn’t dare to call myself the best. But I work hard. I work a lot—on a lot. My process involves putting a lot out there.

MCGINLEY: People get caught up in something being perfect. I try to put things out. I’ve made a few mistakes along the way, but I think it’s important to put the work out there.

COSTA: Before you can put that out there, there’s a lot of censorship that you have to go through, but I try not to be afraid of putting it out there. Whether that exercise was perfect or not, whether the final result was perfect is, to me, often irrelevant. Because it’s what you went through, your way of doing it, that counts.

RYAN MCGINLEY IS A NEW YORK-BASED PHOTOGRAPHER.