WEB3

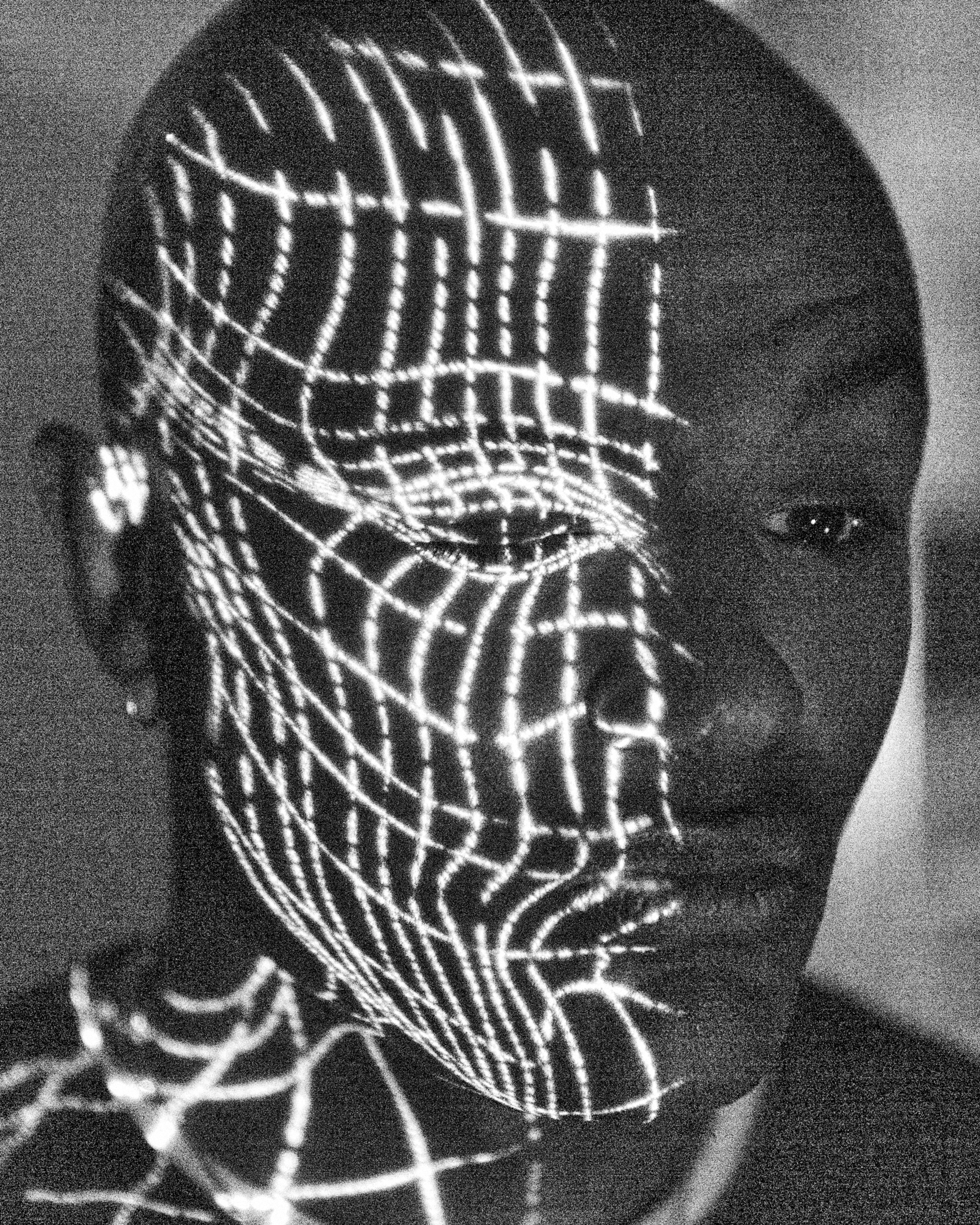

Trevor McFedries Tells Jordan Wolfson About a New Kind of Internet

Trevor McFedries is a baller. A DJ, entrepreneur, and aspiring basketball star, the 36-year-old Los Angeles native is also the CEO of Dapper Collectives, a role he assumed when the non-fungible token (NFT) startup Dapper Labs acquired his artificial intelligence–focused media company Brud. As one of its founders, McFedries gave life to Lil’ Miquela, the uncannily cool virtual influencer who served as patient zero for his philosophy of community-based storytelling (Brud plans to put Miquela’s fate in the hands of her followers). Now, as the internet moves towards a decentralized future—Web 3.0—McFedries sits firmly on its bleeding edge. In 2020, he launched Friends With Benefits, a private online community for blockchain enthusiasts and artists, where membership fees come in the form of digital tokens, and networking takes place on Discord channels. The goal? To create a digital utopia whose denizens can own—and monetize—their creative output. To help us make sense of his vision, the artist Jordan Wolfson, who knows a thing or two about creation in the age of the internet, spoke to McFedries about what the World Wide Web might look like when it’s for everyone, by everyone.

———

JORDAN WOLFSON: And, action.

TREVOR McFEDRIES: We’re rolling.

WOLFSON: Where are you right now?

McFEDRIES: I’m in Miami.

WOLFSON: What are you doing there?

McFEDRIES: My company got acquired a few months back. Some of the team that I work with is in Miami. I was living in Los Angeles, but my basketball trainers and work are here, so now I’m in Miami living the dream.

WOLFSON: Let’s start from a specific place, because I think a lot of people know you, but don’t understand what you do. Can you give me a full rundown of what you do professionally?

McFEDRIES: I am the CEO of Dapper Collectives. It was born out of an acquisition Dapper Labs made of a startup that I founded in 2016 called Brud. My nine-to-five is running an organization of about 40 people. We’re building DAO software— crypto organization software.

WOLFSON: Hold on. We should tell everyone what DAO stands for: decentralized autonomous organization.

McFEDRIES: That’s correct. You can think of a DAO like a company that is governed by a token instead of a CEO. As part of what we’re doing, we’re trying to allow media organizations to decentralize and birth a new chapter of media organizations—in a new era of computing we call Web 3.0. Beyond that, I started a DAO on Ethereum called Friends With Benefits. I also angel invest and make music. Every now and then I get called to DJ. I also try to make time for my personal life, which mostly means training and playing basketball at the highest level possible.

WOLFSON: What do you mean by “the highest level possible?”

McFEDRIES: Basketball is my first love, and my main hobby. I have ambitions and goals to play professionally somewhere in the world.

WOLFSON: Really? Where?

McFEDRIES: I wouldn’t be able to play in the G League or the NBA. It’d be more likely that I’d play in, like, Puerto Rico, a European league, or somewhere that’s geared toward players at the end of their careers. That’s where I’ve set my sights for now.

WOLFSON: But you also created that thing, Lil’ Miquela. Right?

McFEDRIES: That’s correct. Lil’ Miquela was part of Brud.

WOLFSON: Does she still exist?

McFEDRIES: Miquela definitely still exists. The acquisition of our company was born out of our desire to take our traditional C-corp, Brud Inc., and decentralize it. Miquela has ten million–plus fans across socials. In the near future, those fans are going to participate alongside us creators to shape her universe.

WOLFSON: What do you mean?

McFEDRIES: Imagine Spider-Man living panel-by-panel in a comic book, in a world where, instead of a team of ten people deciding what happens in his life, anyone holding governance tokens can vote to decide, for example, whether Spider-Man fights the Green Goblin. That narrative can then be minted as an NFT to a blockchain. When that NFT is sold, parts of the funds go to the people who created the work, either the concept or the actual production of the media itself, and some of the funds flow back to the treasury to support more creation. That’s the core concept that we’re innovating on. It’s the same with Lil’ Miquela. Her fans will be able to decide whether she goes to Paris Fashion Week or Tokyo Fashion Week. They’ll have their say along with the creative team.

WOLFSON: Cool. Is your DAO up and running?

McFEDRIES: Yeah. Friends With Benefits has been up and running for like a year and a half. At first, FWB was just me hacking away at an idea on a weekend. Now there’s 2,000-plus members that have been active over the past year. We have a core team building software products, and there’s a governance token—a FWB token—and with that token, people can vote on proposals that control the budget and the treasury. People use that budget to try to create public goods for the community and great products people want to purchase. The DAO is alive and kicking and always changing. It’s an organism.

WOLFSON: Have people gotten rich off this DAO yet?

McFEDRIES: I imagine so, but also there was a hack. So these things can go both ways.

WOLFSON: You got hacked? Did everyone lose their money?

McFEDRIES: Kind of. There was an original token called FWB. We had tokens custodied in a third party, a company called Roll, and Roll got hacked. So hackers got access to our custodied tokens and sold them. People, including myself, lost a bunch of money. It mostly affected liquidity providers, which was primarily the founding team. I had provided a few hundred thousand dollars in liquidity that all was stolen from me.

WOLFSON: Wow! I’m so sorry.

McFEDRIES: You know what? I feel like every crypto project has its crucible moment, and a lot of them are these hacks. There’s the legendary first Ethereum DAO that went to hell, and other tokens that have had similar incidents that rallied the community around the token. We had that exact experience. Now the tokens are trading at, like, $80. In March last year, it was trading at ten bucks or something like that.

WOLFSON: I feel like not many people know about DAOs yet, but it’s about to explode.

McFEDRIES: I think you’re right. It seems like DeFi [decentralized finance] was 2020, NFTs were 2021, and DAOs will be it for 2022.

WOLFSON: Are you buying art?

McFEDRIES: I try to buy my friends’ art. I have an Arthur Jafa piece here in Miami that I really love. I have a piece from my friend Lucy Bull that I’m staring at right now. There’s a Japanese artist, Namio Harukawa, who I collect. I have a Dee [Diana Yesenia] Alvarado ceramic that I quite like. I have a Narumi Nekpenekpen ceramic I love also. I have SSION here; he’s a musician, a filmmaker, and a painter as well. His real name is Cody Critcheloe. I have a Martine Syms on the way, too. I like collecting art.

WOLFSON: What does your apartment look like? Do you have a view of the ocean?

McFEDRIES: I’m in Midtown, but I have a view of the water. It’s quite simple here. I have some little wooden chairs, and a white sofa that I’m laying on right now. There’s a stand-up desk in one room where I work day-to-day. I have a little music studio set up in the corner of the living room, and a bedroom with a mattress lying on the floor. I don’t know if I’ll ever grow out of that.

WOLFSON: You have a legitimate mattress on the floor?

McFEDRIES: There are sheets on it, but yes, it’s on the floor with tables on either side.

WOLFSON: What else, Trevor? Is there anything you want people to know about you?

McFEDRIES: Good question. The thing that people don’t necessarily know is that I was a recording artist and made creative work for a long time. That’s why I’m trying to make sure that creative people, people who are genuinely bringing new ideas to the surface, are being rewarded for doing so. It’s been incredibly frustrating for me to see really derivative work and the Forever 21 economy bleed a lot of my talented peers dry— people like yourself. I’ve been fixated on trying to create better economic systems for people who are actually making the ideas that bring us so much joy. That’s going to be at the core of what I do for a very long time.

WOLFSON: I don’t understand how that would work. In terms of NFTs? Or are you supporting artists?

McFEDRIES: There’s a million ways. One of the things I was trying to do with Lil’ Miquela was create a model where people who were disenchanted with being public figures could share their work without having to deal with what it means to be a public figure. It can be miserable. The court of

public opinion will try to destroy you as fast as they’ll champion you. The idea that you could just create this figure, this avatar for you to share your creative wares through, was really intriguing to me. Then this thing about blockchains, about tokens—the hyper-financialization of our lives. I’ve had such disdain for it, but if you invert that and try to create better instruments for capturing value, you can attribute that value and pass it back.

WOLFSON: So how would that work? Can you describe the actual model that you’re proposing?

McFEDRIES: Sure. Friends With Benefits is an example of what that could look like. A good comparison for FWB is a Web 2.0 social network like Facebook. You went on Facebook and you made Facebook interesting because you wrote on people’s walls, made photo albums, and poked people. Instead of that value accruing to the edges of that social network, it accrued to the center. Mark Zuckerberg, the investors, people who owned that network, were the ones who benefitted. In a decentralized network like Friends With Benefits, there are ways to say, “Hey, the more you engage with the software, the more value we can accrue to you in the form of tokens.” In Friends With Benefits, if you have tokens, you can participate in the network, and you can see the value of that community you helped create reflected in those tokens. What I’m trying to do is learn as much as I can, and then try to reflect what I think are more equitable and sustainable ways of existing, such that my people—creative, innovative people—can exist. It’s incredibly hard to be creative and make a living right now. I’d like it to be easier.

WOLFSON: It’s really hard. I’m so fortunate that I’ve been able to do it, but for years I made no money at all. I could pay rent, and that was it.

McFEDRIES: You made incredibly groundbreaking work, but I’m sure there were tons of people referencing your work or borrowing your ideas—people in big corporations.

WOLFSON: Totally. That happened with [the ad agency] Goodby Silverstein & Partners. They ripped off my piece in the Whitney Biennial. My uncle was a copyright lawyer and we wrote to them, and they sent me back this threatening 300-page argument about why what I did was appropriation, not why what they did was appropriation. I knew they were copying me because I used to have a website tracker, and you could see IP addresses and LLC names. I don’t think they have them anymore. In the early 2000s, you could see someone’s server and it was like, “Goodby Silverstein.” Even friends of mine who took jobs at Viacom would tell me, “I’m in a meeting right now. And we’re talking about your work at MTV.” And I was like, “Tell them that you just had this conversation with me, and not to copy my work.” But isn’t that just how the world is? I can’t expect to get anything from that because my work comes from so many other artists as well. We’re all walking in a chain-gang together.

McFEDRIES: I agree. We’re all standing on the shoulders of giants. One of the things that I’d love to see championed going forward is attribution. There’s this misnomer that you can’t be inspired and you can’t reference things. I’m 36, and generationally, a lot of my peers were the first to recognize that we had this incredible glut of media we could reference. Instead of actually innovating, a lot of people just use nostalgia as a design crutch, and recreate ideas from the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, whatever. Everything felt incredibly stagnant for a long time. I love the idea that you can reference things and improve upon them, or use them as inspiration to make better things. But literally, just referencing things one-to-one and calling it your own is so boring and terrible.

WOLFSON: It’s always been like that. People have always used anachronistic source material. And when I say always, I don’t mean in the last 50 years. I’m pretty sure it was like that in the Renaissance, too.

McFEDRIES: I’m sure. The challenge is how to incentivize people to inspire others and be inspired by others, but at the same time, create a situation where people can sustain their practices and not feel such disdain for these ecosystems. We want an ecosystem where you can borrow and be borrowed from, but we also want to feel like the world is giving back to us, not just taking mercilessly.

WOLFSON: Do you feel that’s sustainable and realistic? To me, that’s enormously moralistic, a utopian fantasy.

McFEDRIES: I think it’s absolutely achievable, and has been for a long time. You look at the ’90s and there were even outsider artists who were able to make a significant living in a volume-driven media environment, whether that was film, television, music, or whatever. Nowadays, indie rock bands struggle to make a living because the economics just don’t work.

WOLFSON: Totally. The economics for musicians are completely fucked. And it’s all because of streaming.

McFEDRIES: That’s the thing. Knowledge is power that we need to share, but there is this tension for me, in that information wants to be free, but also people need to eat. How can you make information universally accessible, but also individually ownable, at least while living under capitalism? Is there a way to allow people to sell their work while making it universally accessible? That was the great magic trick of NFTs, and why I think people were very, very excited about that innovation.

WOLFSON: Did you listen to my conversation with Beeple [on Dialogues: The David Zwirner Podcast]?

McFEDRIES: I did, yeah. I loved it.

WOLFSON: He keeps talking about the art world that I’m in as “the traditional art world.” And then he talks about the art world that he’s in as this digital, nontraditional space. But you could also say, “What’s the traditional financial model, and what’s the new financial model?” There have been other trends. Five, six years ago, Hollywood agencies wanted to step in and represent artists. I don’t know if you know about that or remember that. But it was UTA [United Talent Agency].

McFEDRIES: I remember seeing that UTA had an art agency, or something.

WOLFSON: UTA made a big pitch for a number of artists, including myself. There was always a lot of cynicism about anything that threatened the traditional art model, which is insane. Basically, I’m giving away 50 percent of my profits. In what other business do you give 50 percent of your profit to someone?

McFEDRIES: Crazy.

WOLFSON: It’s insane. You’re paying for this gallery that has an operation, and is presenting other exhibitions, and is shipping other artists’ work, and has all these employees.

McFEDRIES: I imagine there are tenant costs, and I imagine it’s quite difficult to run, especially a medium-sized gallery. But it does seem ridiculous. I find it cringe when people talk about traditional art versus this new art thing, because so many NFTs feel like Beanie Babies right now. I have a real appreciation for gatekeepers after the music industry blew all of them out of the water. Now we have a Spotify Top 100 that maybe doesn’t reflect the most groundbreaking or interesting work that’s coming out.

WOLFSON: It’s all trash. Music is horrible today. We don’t have great artists anymore.

McFEDRIES: I largely agree. I have friends who [do] A&R [artists and repertoire] at record labels who are just chasing down TikTok kids who made a 30-second snippet that’s trending, to see if they can turn it into a two-and-a-half minute song. It’s pretty bleak.

WOLFSON: We live in such bleak times. I even feel it as an artist. I feel like I can’t express myself. The thing about art, and I had this realization yesterday, is that the quality that makes great art original is its saturation of freedom and freeness. When someone’s so free, you can’t help but be completely original. Everyone’s scared of offending someone else right now. It’s like, “No, I’m talking about racism. I’m not being racist.” If you want to get rid of racism, you have to talk about racism.

McFEDRIES: I totally agree. I was pretty frustrated about it for a long time, until I realized what an opportunity this asymmetry presents. I would say 99 percent of people are miserable and fed up with cancel culture and woke progressivism. I don’t think anyone I know uses the term “woke” genuinely. It’s all ironic. The only thing holding it together is corporate HR. As soon as there are external sources, or capital, or places to realize your creative dreams outside of corporations, that shit all goes away.

WOLFSON: My impression is that people want art back. That’s why people are excited about O’Flaherty’s gallery in New York. The minute you start oppressing people’s freedoms, that’s when subcultures spring up.

McFEDRIES: Somebody’s got to get it right. People are finding ways to punch through it. Hopefully something changes.

WOLFSON: I already think it is.

———

Grooming: Isamaya Ffrench using Burberry at Streeters.

Grooming Assistant: Tash Sultana.