The Last True Bohemian: Mark Bozek and Ruben Toledo On The Extraordinary Life of Bill Cunningham

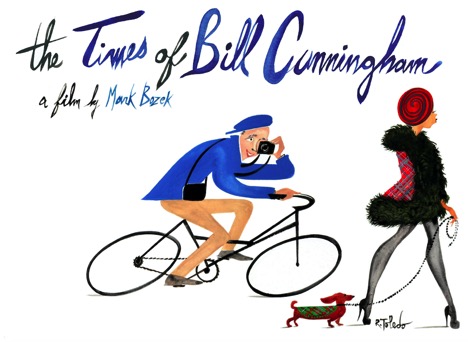

“I don’t like cities, but I like New York. Los Angeles is for people who sleep. Paris and London, baby you can keep,” sings Madonna in her ode to the concrete jungle, “I Love New York.” It’s a sentiment that is shared, far and wide, by those people who leave everything behind and journey to the Big Apple in search of excitement, inspiration, and quelque chose de nouveau. Bill Cunningham was one of those people. The long-admired fashion historian-gone-street photographer lived his very best life riding his bicycle, in his staple blue coat, while taking photos around the streets of his beloved city. His presence, much like his four decades at The New York Times, gave New York society a reason to show up and show off in style. When he died in 2016, the industry mourned not only his eye and precision to catch trends, but his humility and intoxicatingly positive way of approaching life. The Times of Bill Cunningham, a new movie by Mark Bozek deliciously narrated by Sarah Jessica Parker, another New York guiding light, slightly pulls the curtain back on the very private life of the photographer. Born out of a rare sit-down interview with Bozek from 1994, Cunningham himself guides the audience through his New York minute, while intermittently dispersing never-before-seen images from his extensive archive. From his days working at the high-end department store Bonwit Teller to his life at Carnegie Hall Studios, and the camera from fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez in 1967 that kickstarted Cunningham’s career, the film retells each story as if it just happened yesterday. Although the film touches on the well-known parts of Cunningham’s life, it also touches on the sadness the photographer bottled inside as he lost friends to the ’80s AIDS epidemic and struggled with his Roman Catholic upbringing. The Times of Bill Cunningham, much more than just another film about a late icon, is an homage to “the last true Bohemian,” as his friend the artist Ruben Toledo, who also drew the movie’s poster art, told Bozek. Below, the movie’s director and Toledo reminisce about the late photographer’s impact on New York society, old and new, his favorite diner, and why we should all wake up everyday and dress for Bill.

———

RUBEN TOLEDO: When Mark rang us up and told us about this footage, I couldn’t believe it. I could not believe that Bill had sat for anybody to talk about himself because he was so private. That must’ve been a shock for you, Mark, having that happen.

MARK BOZEK: I learned that it was a shock later on because I didn’t know this was the first time he had ever sat for an interview. I became much more appreciative and felt lucky that he picked me on that day to open up to.

TOLEDO: Most of our friends couldn’t believe that he had spoken to anyone like this—so open about his life for an hour. It was having a one-on-one visit with Bill again, which was really precious, so just as a document for that in itself is amazing. Learning so much more about Bill and going deeper than before was pretty amazing. We all know these stories peripherally, here or there. All of us feel really proprietary over Bill because everyone has their own personal Bill story, and knows Bill from different decades. He’s been around a long time, so he tied a lot of different people together and a lot of different social scenes together. So to have that happen is pretty rare. For me and for [the fashion designer] Isabel [Toledo, his late wife], to know that he felt comfortable enough to open up to Mark in that way was pretty rare.

BOZEK: I initially thought it would just be a little side project. I didn’t know it was going to completely consume my life for three and a half years. I knew if I could get people like Ruben and Isabel and the others, they would then help me plug a bunch of the holes. At that point, I hadn’t had the chance to do much research.

TOLEDO: All the Bill Cunningham family tree helped Mark put it all together, I think. You certainly were keen and open to having that happen. New York is a labyrinth of cultural influences, people, social classes, interests, and focuses. Bill was being a little social archeologist, and Mark had to be that too, to try to dig up these trenches and these tunnels to get to the source of things.

- Art by Ruben Toledo.

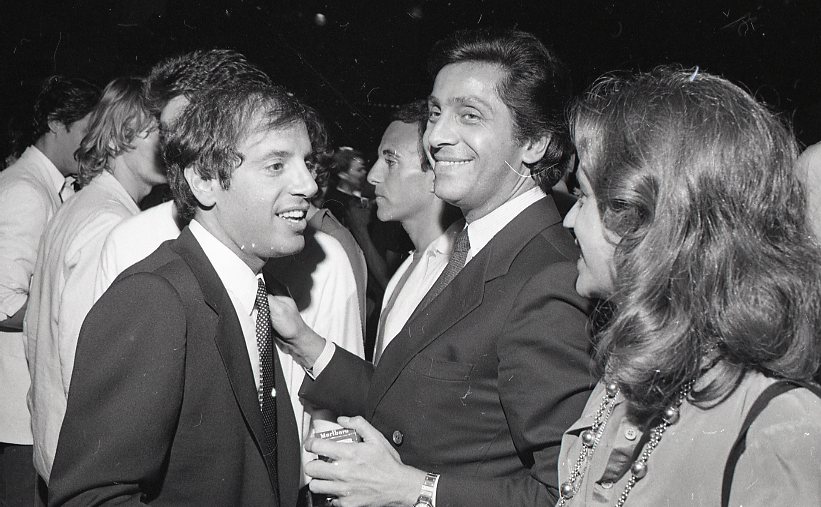

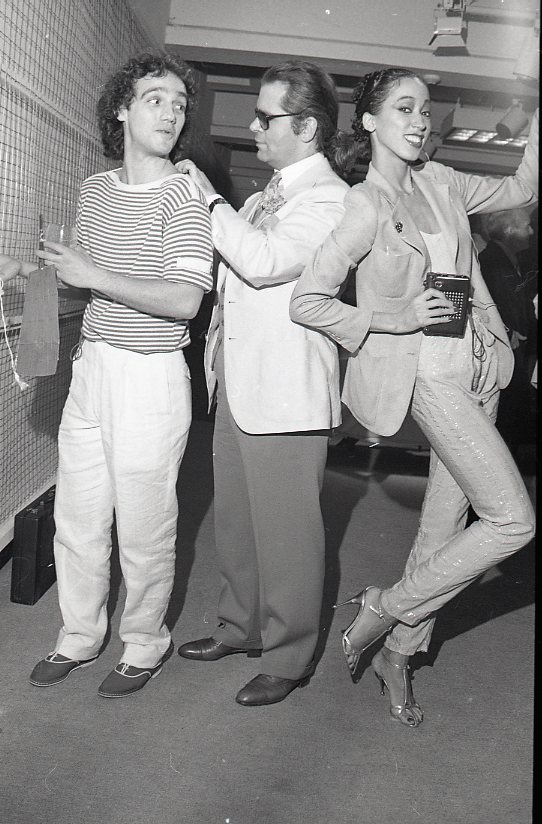

BOZEK: What I loved so much about how this process has gone is that people like Ruben, who was so close to Bill, designed the poster for the movie. Pat Cleveland, who was also instrumental in Bill’s life during the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, and during the whole Antonio Lopez and Karl Lagerfeld scene—she sings a song at the end of the movie called “Tonight Josephine” that she recorded a couple of years ago. Sarah Jessica Parker, who was this great voice of New York, said yes after one email. She said yes without seeing one frame of the film.

MACIAS: Ruben, on that note, you made the main art for the movie—what was that like for you? Did Mark ask you to be involved?

TOLEDO: First of all, Mark had to stop me because I wanted to make a whole animated version of the movie, of course. I have so many drawings of Bill, going back so many years. Whenever Bill would write me a note, we would write a note back, so we have a ton of wonderful correspondence. But of course, if he described something with a photo that he would send us, I would describe something back as a drawing. So Mark had to just contain me to the post and the opening title, but that’s probably another animated cartoon version of this coming up soon. It was such a treat because Bill to us is one of our cultural New York City landmarks like Andy Warhol is. These people we met very early on were wonderful guiding lights for what creativity is all about in New York, and how you lived life as an artist.

BOZEK: What was the fanciest restaurant you ever went to with Bill?

TOLEDO: [Laughs] Fancy, no way. Well, we actually were caught in events in fancy places, which we would all laugh about, so there we were.

BOZEK: But when you actually sat down and had dinner with him…

TOLEDO: We would have dinner with him every weekend at his favorite greasy diner just down the street from Carnegie Hall. It was a diner he went to for ages. He knew all the waiters and the dishwashers, and they all knew him and what he liked. On Saturday nights, it always ended with us going over to the newsstand to pick up the Sunday New York Times. He was always delighted to show us his page and what was going on in the pages of the Times.

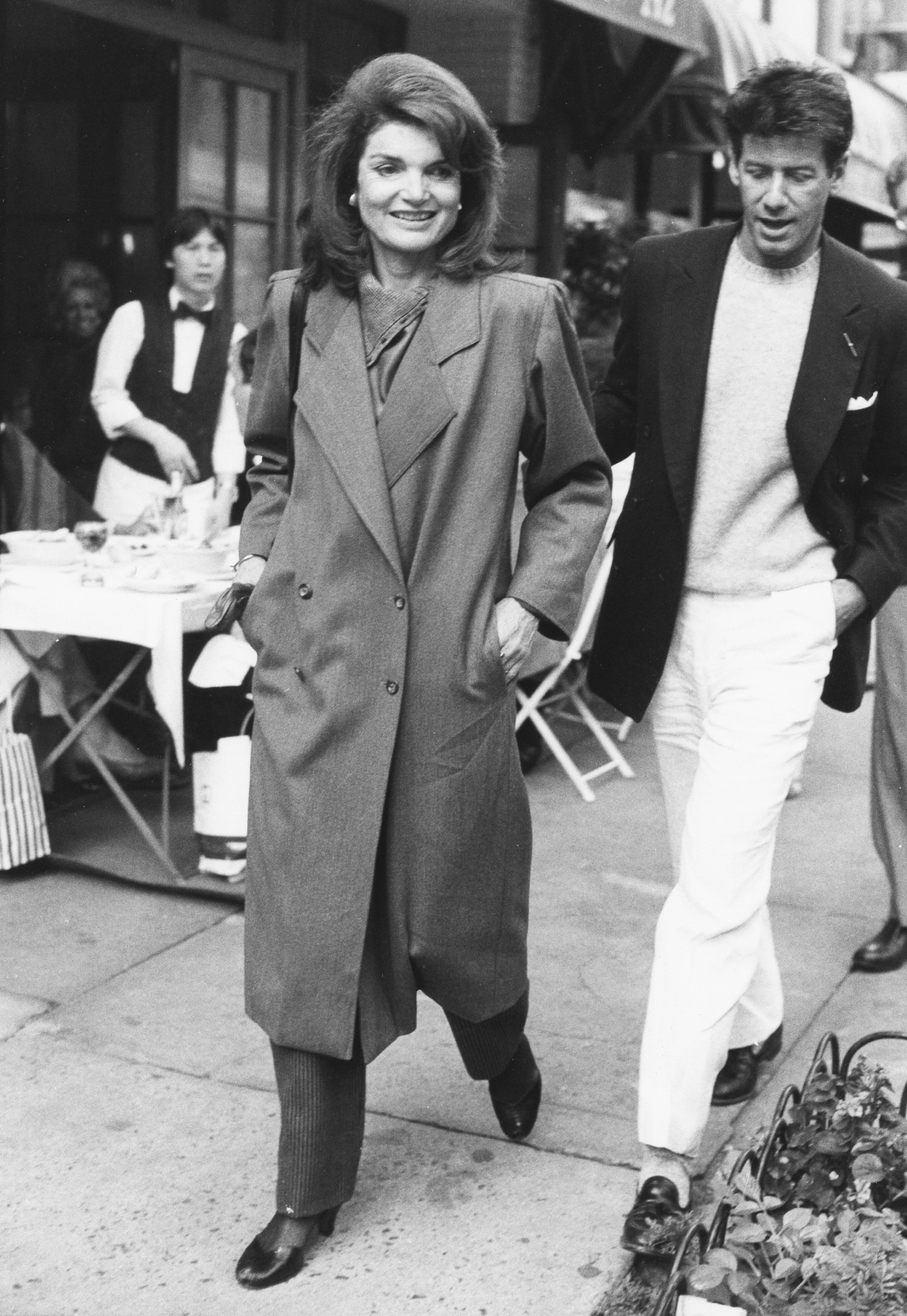

BOZEK: When he was doing the On the Street and the Evening Hours pages at the Times, which went on for 30 years, the newsstands on Saturday night on the Upper East Side were just teeming with society people or their servants, running out to get the paper to read the Style Section and see if they made the pages or not.

TOLEDO: As you know, Bill’s pages, when he first started, the pictures were much larger and much less of them. As the New York social scene heated up and the event world heated up too, the pictures got smaller and smaller because there were more and more people that you had to put in. Eventually, it became this beautiful, almost digital collage of colors. People really did dress for Bill, and if there was an event and Bill didn’t attend, it almost didn’t happen.

BOZEK: Last night, Ruben, I was with Susanne Bartsch. She was my guest at the screening last night at the Angelika. She hadn’t seen the movie before, and of course, she came as if Bill was photographing because, like always, she was dressed. She told great stories. Bill used to call her the Swiss Miss because she’s from Switzerland.

TOLEDO: Yes, the Swiss Miss. [Laughs] I remember meeting Susanne super early on when she had a hat store in Soho. In fact, Bill might have taken me there to say, “Did you see this new store that opened up?” I was working down in Soho at a store called Parachute, it was maybe 1980, and there she was with her beautiful hat and maybe wearing three of them at once. Bill is photographing everyone and everything on the scene. Again, that’s what makes him the Weegee of fashion. He’s always on the scene super early on and capturing the essence of things when he’s at the scene of the crime, and the crime happens to be fashion.

BOZEK: I remember I had worked on the film for gosh, almost two years, and I still hadn’t any pictures that Bill shot in the movie because I hadn’t been able to connect with his family, and in particular, his niece [Trish Simonson], who Bill left his estate to. I met her up in Orangeburg, New York, where the archive is stored. We were sitting in the lobby of the Holiday Inn. We ordered two glasses of Holiday Inn white wine, and I opened my laptop and I played the movie for her there, and she was weeping by the end of the movie. As Ruben had said, Bill kept many parts of his life very separate. He loved his family in Boston, but they had no clue, other than that Uncle Bill was a photographer. He knew exactly what he was doing by putting her name on that will because she was family, but also because he had a sense that she was going to become as ruthlessly protective as his close friends. Suddenly, after almost two years of having the film, watching it, and experiencing those things, suddenly I was in the archives, and I was like a drug addict in a drug den. Considering that there are 3 million photographs, images, and letters, they were really organized.

TOLEDO: So you can basically do three more films of just silent films with just the incredible imagery going one after the other, like a flipbook.

MACIAS: You guys both have very close connections to Bill in very different ways. After watching the movie and seeing the cultural impact that Bill stands for, what do you hope that people get out of this movie after watching it?

TOLEDO: It’s a first-hand account of an artist by the artist himself. It’s so intimate. It’s so precious to get inside somebody’s head like that, and especially someone who’s that private. I think all of us artists are super private, you know that. We work a lot with students and we mentor a lot of kids in school, art, and fashion—Isabel did. It’s so important for them to know that there’s another way to exist. Bill lived that life. I think we were all lucky to live that life in the late ’70s, where anyone who became an artist at that time, they learned how to be a living Bohemian in the middle of the frantic energy that is New York City. I think it allows the young generation to understand how you can live in that whirlpool and that stew of life, but still keep your soul, your personality, and your individuality.

BOZEK: I never really set out to make a fashion documentary. It was pretty clear to me early on that this was more, and I hope it will be more than just about a fashion photographer. Bill, of course, never referred to himself as a fashion photographer. He was much more proud of the fact that he was a historian. In having done festivals now for the last year and a half of screening the movie, people seem to be much more taken of Bill as a person and as an artist. I’ll screen it for the rest of my life to anybody who wants to learn about this man. I hope it reaches people beyond the fashion and society worlds of urban cities.

TOLEDO: I think this film should be in the national archives because it’s that important. It is history in society, and it’s absolutely something that’s just disappeared. Bill was the last of that kind of Bohemian lifestyle. It wasn’t just Bill, it’s the people around him and the life he led, and the people that led that life with him at Carnegie Hall and beyond, that extended family tree that he wove for that many years. This is a really important document.

———