Teju Cole

I don’t think about it as a way of convincing people, it’s just a way of testifying to your presence in the world. TEJU COLE

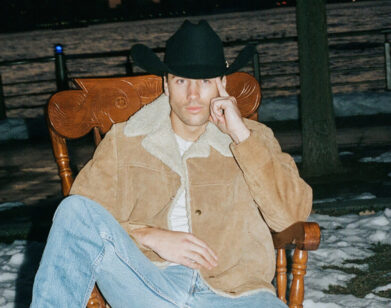

The world has changed lately. Or maybe it hasn’t. Maybe it’s just that writers are once again finding new stories to tell and new ways—and places—to tell them. One of the writers in recent years who seems especially versatile, courageous, and hopeful (even on subjects that seem so hopeless) is 38-year-old author Teju Cole. Born in Michigan and raised in Nigeria, Cole turned the rather innocuous activity of wandering through New York City into a contemporary rumination on culture, death, absence, and individual odyssey in his 2011 novel Open City. Never have I been told so often by New Yorkers that I should read a novel set in New York as I was the year Cole arrived with his ambitious, experimental ramble that appeared to be the post-9/11 book everyone was waiting for but no one was expecting to move so quietly to the front of the shelf. As it happens, Open City was not Cole’s first book. His novel Every Day Is for the Thief was published by a Nigerian press in 2007, collected from a series of blog posts that narrate the fictional return of an unnamed protagonist to his hometown of Lagos and the weeks he spends moving through the dire streets and markets and buses and social circles and police stops and scarred memories of a city with no center, no hold. In just one of the narrator’s astute observations, he says, “Precisely because everyone takes a short cut, nothing works, and for this reason, the only way to get anything done is to take another short cut.” As with all of his work, Cole writes without shock absorbers, and the ride is as terrifying as it is gorgeously set. This month Random House is releasing a new edition of Every Day Is for the Thief, including photographs shot by the author on more recent trips to Lagos. But Cole is not the kind of writer to go quiet in between publications. In fact, he’s always writing and always publishing—some of his most fascinating and political literary explorations have occurred on his Twitter account, where he plays with new structures and forms, pens emotive tales of power and resistance, and occasionally bends the mind through unbelievable vectors considering the 140 character count. Cole currently lives in Brooklyn. I met up with him at a restaurant in Dumbo. I asked them to turn the music down.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: This is your second novel in terms of a finished book at an American publisher, but you actually wrote the material for Every Day Is for the Thief before you started Open City. So, in a sense, this could be considered your first novel.

TEJU COLE: It had a funny life. I went to Nigeria in late 2005. In January 2006 I did a series of blog posts about the trip. In the writing, the story became a little distanced from my own narrative. It was a way of grappling with the trip. It became a fiction but it still stayed quite close to the experience. I set up this blog and I did one post a day for 30 days—a 30-day writing experiment, which got quite a number of readers and people telling each other, “This guy’s writing about Lagos in a somewhat different way than we’re used to.” When the experiment ended, the blog disappeared. I took it offline.

BOLLEN: So the blog was a pure vehicle for this project—you weren’t already blogging.

COLE: It was a pure vehicle. A few months later, a couple of Nigerian publishers said, “What ever happened to that thing? We want to print it.” I said, “Well, it’s not really supposed to be a book, it’s supposed to be an experiment.” There is an element of conceptual art that attracts me—this idea of making something alive in the moment. It’s something I do a bit with Twitter now. But it was Cassava Republic press, which was at the time a fairly new publishing house in Nigeria, that convinced me to turn it into a book. That’s why there are also photographs, because that’s what you do with a blog post—you put up pictures.

BOLLEN: Did you go to Lagos specifically thinking you’d use the experiment for a writing project?

COLE: Absolutely not. But you go to the city where you grew up 13 years later and it’s a total shock to the system. So much has changed in you, so much has changed in the city, so much has not changed in the city. Just in the few weeks I was there, I was constantly absorbing every detail, hungrily recovering my childhood in a way. That visit was characterized by such extraordinary intensity. And so was the writing of it. It’s still the most intense writing I’ve ever done. For 30 days it was like I almost didn’t exist as a person. I would wake up and write my thousand words in the morning and spend the next six or seven hours fussing over them. It almost ended my marriage. [laughs] She was like, “Where are you?”

BOLLEN: Beware of marrying a writer. Did you find an immediate audience with Nigerian readers?

COLE: Yes, the first few days, I had 15 or 20 people reading it. But by the time I’m on day 15, I’ve got a few hundred people, because word of mouth has spread among Nigerians in particular. But when it came out as a book, it had a whole new life of its own. Because writing in this seemingly unfiltered way about Lagos, about our contemporary situation, and publishing it as a book wasn’t really done. Even people who tried to write about Lagos, for the most part, had written fairly conventional type of novels. And this was this weird thing that was sort of a memoir, fiction, and travelogue. But this is the kind of writing I do. I try to write with freedom. Funnily enough, I wrote Every Day Is for the Thief in January 2006, and I started writing Open City in November 2006 as a way to procrastinate to do the edits for the book version. So it’s a younger book, an earlier book, but not by a whole lot.

BOLLEN: In both books, I’m sure you’ve been confronted with the confusion between you and the narrator. That happens no matter what a person writes, but since both of your characters are young Nigerian men who live in New York, I’m guessing you’re constantly deflecting the disguised-memoir perception.

COLE: The two characters have much in common, but not in common with me. The characters for me are very clearly fictional—because of their biography, but also because of their views, which conceivably could be mine, but that’s the thrill of writing fiction, to create a convincing character. What you’re doing is not plausible deniability; you’re actually exploring other modes of being. I’m not putting things into Julius’s mouth in Open City so I can say, “Oh, that’s Julius, not me.” That’s not the purpose of doing it; it’s just saying Julius exists for his own sake, as his own person. I still get angry letters about the ending of Open City, because people sort of assume that he must be me, or he must be nice. But life is not that way, literature is not that way.

BOLLEN: Readers often have a hard time accepting the fact that main characters can be unlikable, even, in moments, absolute jerks. But writers aren’t inventing friends. Sometimes I think people read like they’re trying to date the characters. Like, “I want to fall in love with you, I’m trying to fall in love with you, but you’re being an asshole!”

COLE: Yeah, somebody actually said to me about Open City, “Why did you rape that girl?” She wrote a letter and said, “Oh, by the way, I know it’s fiction, but I just got to ask, why did you rape that girl?” And I just thought: why would you assume that? But in a perverse sort of way, that’s what we as writers do. We invite the ambiguity. We are a little bit frustrated by it. But we invite it.

BOLLEN: Since you wrote Every Day Is for the Thief in 2006, there are a few reflections that you may no longer feel connected to, but one that struck me was an observation your narrator had about American writers who don’t have a Lagos to cull stories from: “I suddenly feel a vague pity for all those writers who have to ply their trade from sleepy American suburbs, writing divorce scenes symbolized by the very slow washing of dishes. Had John Updike been African, he would have won the Nobel Prize 20 years ago. I feel sure that his material hobbled him.” Do you feel that having grown up far beyond the suburban sprawl of America has given you a richer well of material that hasn’t already been exploited to death?

COLE: Except that, of course, I followed that book up with a novel about New York in which almost nothing happens. [laughs]

BOLLEN: You just guessed my retort.

COLE: I don’t think I actually have any scenes with the washing of dishes to symbolize a divorce. But close enough. When I go back and read Every Day Is for the Thief, I like it almost like one likes a first child. There’s something unfiltered, and almost indefensible about it. Open City is much more layered, to a degree that some readers find frustrating. Because Julius cannot decide about anything. The narrator of Every Day Is for the Thief is just right there, responding directly. I love that line in the song Mos Def did with Busta Rhymes called “Do It Now.” In his verse, Mos says, “Yes, the first cut should be the deepest.” And I sometimes think of that in relationship in Every Day Is for the Thief in that I will probably never write anything as fearless. It’s not a hard book to read. Because it just goes in.

BOLLEN: The Lagos you describe basically is one of the knife’s edge, with no safety or protection, no power structure to keep it in check. I feel like the beating heart of the book is the scene where the 11-year-old boy steals a baby at the marketplace and he’s caught by onlookers, bound in a tire, and set on fire. And then all of the participants just disappear. It’s a city of chaos and culprits and then a blameless drift.

Whether you’re fictionalizing or writing in a straightforward way about life, there is always a core of honesty in that ambition. Teju Cole

COLE: You know, right now I’m writing a book about Lagos that’s nonfiction. It’s a different kind of book, in part because it’s going to come out like eight or nine years after Every Day Is for the Thief. So when I wrote Every Day Is for the Thief, I went back for the first time in 13 years, and it’s about somebody who has been away even longer. Since then, I’ve gone back to Nigeria every year, sometimes twice a year. My knowledge of the city is so much more intense and so much deeper, but now I’m experiencing it with a lot more nuance. But the argument I want to make is that sometimes nuance is not everything, sometimes you need a raw response, you need somebody to write an On the Road kind of thing on an area of darkness that somehow plunges you directly into that space. Because normally, for a Nigerian author to write about lynchings in Nigeria, it’s like, “Oh, I can’t write about that because foreigners might read about it and get the wrong idea.” But I don’t care if you get the wrong idea, I just want to say: this happens, and it’s kind of fucked up that we live in an environment where life can be cheapened this way. What has happened to this population that makes them so brutalized? But there’s theft around New York too. And if it were New York in 1912, there was a fair chance the guy’s going to get lynched. There was a lot of jungle justice. People would get pulled out of prison and hanged by irate crowds. It doesn’t happen here anymore, and it’s interesting to me that there are societies in which this happens. It has to do with confronting a modernity that is as yet unsettled. And people don’t have a lot of faith in the judicial system. This is a society in transition. I think maybe it’s helpful for a reader to know that this is a book that’s set in 2005. Lagos has changed, not as much as we would like. But that moment was very much one of transition. Long years of military rule had ended; we had democracy for the first time in many decades, and we simply were not used to living with each other yet. There was a lot of crisis; there was a lot of violence, theft, robbery, lynchings. Those things are still there but they’ve been considerably reduced.

BOLLEN: For an American reader, the book turns a strong, harsh light on a city we usually don’t have access to on that kind of intimate level.

COLE: It’s a guidebook in negative. As someone once said to me, you describe Lagos so well I have no intention of ever visiting. [laughs]

BOLLEN: But this gets to the crux of one of the things that interests me about your work. We take for granted that most Western writers are coming from a neoliberal mind-set. But so few of our contemporary writers could actually be described as political. It seems to me there has sadly become this separation between politics and creative work in America. You’re one of the few writers who manage to inject your fiction with a very clear political message without it toppling into propaganda.

COLE: I came to the U.S. at 17, and you sort of develop as a young person with a political awareness, trying to figure out where you fit in this society. I was born in the U.S. but I always lived in Nigeria. I was born in Kalamazoo, Michigan. When I came back for college, I knew nothing about American life, or even being a black kid in the Midwest. I knew nothing about the struggle. I knew nothing about what it means to be black in America. All I knew is I’m good at school, and the system of rewards that is set up in this country is apparently open to me. It takes me about seven years of being in the U.S., or maybe even beyond, before I start to realize that I’m a black American who’s subject to both that history, and that system of disadvantages. Because for a long while you can sort of stick your fingers in your ears and go “la-la-la,” and you meet white folks who tell you, “Oh, you’re well-spoken, you write well, you can do fine.” And this is something that every black immigrant in this country has to deal with. You slowly realize you have common cause with African-Americans. And you have common cause with anyone who’s disadvantaged, anyone who is pushed to one side because of their gender or their sexuality or their disability or their race. They start to make sense to you as a person, in part, because you’re systematically disadvantaged in ways you might not even be aware of, or because people use you as a kind of valve to escape other pressures. For example, I can become the friend who listens to hip-hop with you or go to a classical concert with you, I could take you to the museum and talk all day, I could easily become your good black friend. And then you don’t have to worry about anyone else. It takes a lot of time to figure out your position in this fucked-up system. Okay, fine, so you figure out your positions. Does that then mean you become Elijah Muhammad or Amiri Baraka? Do you then become inundated by the polemical aspect of the hurt? Or is there another way as an artist to speak?

BOLLEN: For me, in high school and college, Amiri Baraka was always the black-male-poet inclusion in every 101 poetry class or modern anthology. He was the black friend chosen for the white reader. Which always surprised me because he was so firmly against being slotted into that kind of persona. Maybe I’ve been thinking about him because he just died, but I did wonder if his politics ultimately destroyed his poetry. Perhaps that’s an unfair generalization.

COLE: But, you know, it may not be too far from the tree. I have to say, I’m deeply moved by how much he meant to the people who matter a lot to me. I’m not particularly intimate with his work, but I also try to keep two things in balance—on the one hand, there’s really no excuse for being cruel to others, and that seems to be a part of his character. He was misogynist, he was anti-Semitic. I think he was also queer-baiting.

BOLLEN: Yes, I believe he was.

COLE: I’m not going to give him a free pass on these things, just because he’s a black writer. Why would I do that? But on the other hand, you never want to deny the trauma that leads to a kind of psychic deformation in people. And if Amiri Baraka is screwed up in certain ways … Or if Ice Cube, when he’s in N.W.A, he’s delivering lines that you might not necessarily want recited at a White House concert … Well, what made him that way? Is gangsta rap the problem, or is he speaking the truth about the fact that oppression traumatizes people, why is that so hard to talk about?

BOLLEN: Actually, if you think about the white-washed glorification of Allen Ginsberg, it’s hard to read his poems as in any way political today because the culture has embraced the myth of him as a quirky lovable misfit Beat so entirely. All of the rough edges have been smoothed and polished. So there’s something to be said for remaining un-reclaimable.

COLE: There’s something to be said for people who allow their trauma to exist, because it indicts the traumatizing system. But for me, personally as an artist, whatever trauma I’ve been through has not been in the same order, so I need not take on the forms of that trauma, you know? But I still need to find ways to speak truth to power. So art is really important to me in that regard. I actually don’t think about it as a way of convincing people, it’s just a way of testifying to your presence in the world. For example, what I do in Twitter, and all of that, I say to myself, “Look, I have all these people who are following me, what do I say to them? Am I just going to be here to entertain them, or am I going to play the convenient role of angry black man for them?” The answer is neither. I am a creative person. Why should that not just be part of everything I do and still point attention to the things that matter to me? [Gabriel] García Márquez says, “Everyone has three lives: a public life, a private life, and a secret life.” But the thing that really connects those things for me is my attitude to art. I put a playlist up in my Twitter feed this morning, which is a soundtrack for the global war on terror. Okay, maybe that’s a political message, but that is actually not so disconnected from my secret life, because it’s the music I listen to, that’s the way I want to think through the predicament we’re in. I process this through listening to rap. So anything that I do as an artist that interfaces with politics expresses my own deeper self. I think whether you’re fictionalizing or writing in a straightforward way about life, there is always a core of honesty in that ambition. Even when you’re making things up. And when you hit that mark, you know it. Just as you know when you fail to hit it. And you also know sometimes from the responses of people you respect.

BOLLEN: And you know when you’re affecting a wisdom that is actually a front—when it only sounds like a meaningful response. I think there’s a lot of writing that feigns meaning but there’s nothing substantive behind the words.

COLE: Or when somebody is trying to be provocative, for its own sake, which is the other extreme. But if you can just try and show up in the scene, and acknowledge your own weaknesses, and your own imperfections, and your own weirdness, it connects on some level. For example, as weird as Kanye is, he’s doing something really valuable. I don’t think he’s the most arrogant guy on the scene. I think he’s actually one of the most self-questioning and unfiltered. And he’s just trying to figure out, why do I have such strong response to such a variety of things? I find Kanye so much more interesting than Jay. Jay’s not going to sit there and say, “I know I’m not doing it right, but I’m trying to learn.” No Jay’s like, “I’m the king, screw you.”

BOLLEN: If you’ve already won the game, why keep playing?

COLE: To be fair to Jay, he actually grew up in the hood.

BOLLEN: Kanye grew up more Midwestern middle class.

COLE: You can’t judge anybody’s hustle. But Kanye’s more interesting because he’s living … He’s almost like a Philip Roth character, if you think about it. He’s working out his neuroses in the most out-loud, elaborate, public way.

BOLLEN: Are you working out your neuroses on Twitter?

COLE: No. Well, a little bit, but not as much. I think I’m much more controlled.

BOLLEN: I loved the seven short stories that you did last year on Twitter involving drone strikes, using the first lines of famous novels. “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself. Pity. A signature strike leveled the florist’s.” Or “Call me Ishmael. I was a young man of military age. I was immolated at my wedding. My parents are inconsolable.” They remind me of the exercises that Hemingway supposedly did for a short story in six words: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” Twitter’s like that—how do you tell a story in the constraint of 140 characters.

COLE: Of course I’m attracted to the formal properties of that brevity, but I also write these stories because I feel them. When the Iraq war started, I had ulcers because I was like, “What if my grandma was living in this city? How would I feel?” In 2003, I remember thinking, “I cannot believe we’re about to just go in there and kill … What the hell is going on?” And I feel that way strongly. Because I think that partition that people have between those of us here who are obviously on the right of good, and those poor bastards over there who are not us. I don’t have that partition. I grew up in a middle-class Nigerian family. Half my family is Muslim. My grandma is Muslim. She’s not literate. She is like one of these women you might see having their door kicked in in Fallujah by American soldiers. There’s really no difference. So I could not mentally make that gap. A lot of the things people think of safely under the banner of foreign policies are for me very close to the skin. So I am working out some neuroses on Twitter. Clearly, I’m not Kanye—I’m not going on about my sex life or about my partner, I don’t have kids, it’s not on that level.

BOLLEN: You also did a Twitter series contemplating strikes on London. “Some say incinerating Buckingham Palace would send a message and next time Britain will think twice before selling nerve gas. I don’t know.” It’s our thinking of “over there” refracted onto an ally much closer to home—those we do see as like ourselves. I just don’t see other writers making these kind of loaded works—at least not American writers.

COLE: Yeah, which is kind of our job, as thinkers and writers, to challenge that kind of division. Almost every novelist of note, in Mexico, in Spain, in France, in Italy, they all write politically, for newspapers. They all have columns. This is what you do in Africa, for sure, in Nigeria, in Kenya, in South Africa. The writers that I know are people who are called on to address the issues of the day. Someone like J.M. Coetzee might say he’s reluctant to do it, he doesn’t think the writer should be called an oracle. Okay, I understand his hesitation, but he does it a lot more than most American novelists do it. I don’t know what the problem is. Is it our system of rewards that allow people to sort of quietly, safely cultivate their patch, stay safe, know your audience, give them what they want. Or you’re a writer, so all we want out of you is a book every four years. That does not seem natural to me. Is there a vague worry that people might think I’m being hectoring or hectic? But then if you’re worried, you won’t do anything, you know? It’s a deeply felt gesture. But this is what we mean by the political. Just tiny little acts of shifting the center. Why do we assume the center is always on America’s white Anglo-Saxon heritage? In the books I read, the music I listen to, the stories I tell, without setting out an agenda, I just want to testify to my own life that the world is big. And it’s involved with us and we’re involved with it. I think what I try to do is, just say, “Look, pay attention to the small things in the world, speak the truth as best as you can, admit to the fact that you’re not as good as your most earnest fans think you are, you’re not as bad as your haters think you are. You’re just one person who’s testifying to an experience of the world.” But it’s very rewarding to me, that the particular experience I’m testifying to means so much to certain people.

BOLLEN: I think there’s something to what we talked about earlier—that to do honest, meaningful work doesn’t mean that you are trying to please an audience. Your job as a writer shouldn’t be to win as many admirers as possible, something that gets a little confused in the current absorption with the number of followers everyone has.

COLE: If you try to write from the private self, the secret self, it will connect with someone out there, and you don’t know who. And that’s kind of what keeps you going. What is Every Day Is for the Thief about? Essentially about one person moving through a space. That’s really what it’s about. Observing, trying to find a home for himself inside this complication of war. It happens to be set in a complicated Lagos. But it’s about a little soul trying to find a place to rest. And I think people who respond to it respond to it on that basis. Not because they want the details of Nigerian politics.

BOLLEN: In your Nigeria, though, there are break-ins, police graft, crashing airliners. It isn’t America. It’s a bit of a less Updikean landscape to find that place to rest.

COLE: I think we assume safety in the U.S., basically. If something crazy happens, it’s like, wow, that’s crazy. And in Nigeria, if something crazy happens, it’s like, life happens. And so to think about a space in which life is so contingent is also so interesting to me because I live in a place where there is an expectation of safety. In Nigeria there’s no such expectation. There’s always something going on. There’s one part in the book where I talk about this profusion of stories assaulting you all the time. But, you know, maybe the fact under American life is it’s not that safe either, but we’re just good at hiding things away. A lot of people are miserable and a lot of people are struggling and, of course, people are mortal.

EVER DAY IS FOR THE THIEF COMES OUT TOMORROW, MARCH 25, VIA RANDOM HOUSE.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IS THE EDITOR AT LARGE OF INTERVIEW MAGAZINE. HE IS ALSO A FICTION WRITER. HIS SECOND NOVEL, ORIENT, WILL BE RELEASED BY HARPERCOLLINS IN EARLY 2015.