The Vestal Version of Idaho

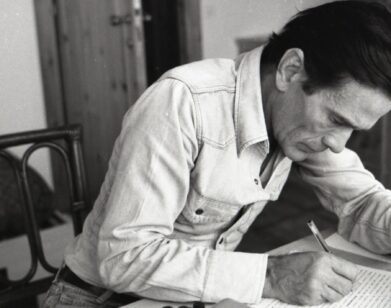

ABOVE: SHAWN VESTAL. IMAGE COURTESY OF DAN PELLE

Shawn Vestal’s short story collection Godforsaken Idaho (New Harvest) is violent, full of dreamy ache. Vestal writes about an absurdly and often hilariously heartbreaking Heaven, where you can order food from any moment in your life and family members and mistakes haunt you. And whether it is celestial beings, father-son criminal duos, or murderous missionaries, Vestal draws vulnerable, beautifully bruised yet resilient characters. Full of Mormons and lonely pockets in the middle of America, these tales transform small towns from monotonous places to ones full of life. Vestal’s pages are populated by liars, con men, families fighting to connect, and lovers struggling to save themselves or each other. Faith is a theme that also runs throughout Vestal’s work and adds illumination to even his darkest tales. We spoke with Vestal about his Mormon upbringing, why family bonds are the strongest, criminal activity, Pulp Fiction, and solitude.

ROYAL YOUNG: Why Idaho?

SHAWN VESTAL: Home for me is Idaho and Mormonism. That’s my childhood. I grew up in Southern Idaho, so those things are just the material of who I am.

YOUNG: Were you raised in the faith?

VESTAL: I was. I grew up in a very faithful, large Mormon family.

YOUNG: How large is large?

VESTAL: I’m the oldest of six kids. But I have stepsisters and half-sisters that got into the mix later. Most of my family is still devout. My brother is a bishop.

YOUNG: Are you?

VESTAL: No, I left. I was leaving inside my head and heart by the time I left their house.

YOUNG: What does that look like? I’m a Jew from New York, and with Judaism, you can culturally still be in it even if you don’t practice. Is Mormonism the same way?

VESTAL: To some degree, it depends on each family. In broader cultural ways, I’m not a part of it, mostly because I don’t choose to be. But then there’s always the stuff you just can’t get rid of. The attitudes and the practices are still there in some fashion. But many Mormon families have wide ranges of devoutness. I know a lot of families who accept their black sheep. My mom has always been sort of broken-hearted by the choices I’ve made, but she has never been less than, or anything but, my mom. If there was any shunning, that came from me, not them.

YOUNG: It did seem to me that a lot of your stories are about disconnected families or families that hurt each other. Where does that come from?

VESTAL: [laughs] Not to be too directly cause-and-effect in terms of my life, but it probably has something to do with my father, who was kind of a spectacular failure at a certain point. He was a businessman and man about town and church leader, and then he got caught forging a bunch of checks. In our small town, it was a prominent crime, so we had several years of him in and out of our lives. When I sit down to write, I always end up about family or failures of fathers. I don’t intend to. It just squirms out.

YOUNG: Interesting that your second story is about a father who takes his son into the criminal fold. Did you ever feel tempted to partake in that activity?

VESTAL: No, but I have the desire to make that connection. In that story, the son is desperate for a connection that maybe isn’t all that great for him. I sometimes fear that being a more or less moral and honest person is based more on not being forced into a corner where I was desperate enough to be put to the test. I could probably be a criminal if things got bad enough.

YOUNG: I think a lot of people could. That’s something we’re so fascinated with, the “stealing a crust of bread to feed your family” question. Then again, being a writer is just a step up from criminal. A small step. [laughs]

VESTAL: [laughs] Yeah.

YOUNG: I also thought there was this theme not only in craving connection, but also in forgiving each other. Do we have to forgive the people who’ve hurt us, or do we have to forgive ourselves?

VESTAL: That’s something I find myself thinking about a lot. Forgiveness has something to do with accepting things that maybe you can’t forgive. Ignoring things and deciding that connection is more important. Family and connection is still what we need and want and what can possibly redeem us.

YOUNG: Why is that? Is it because our families are really the only ones who can explain our own lives?

VESTAL: I think that’s a good way of putting it. Without what we’ve done and who we’ve been, we aren’t anything. People who we share memories and experience and love with, at the end of the day, those are the people who are important to me. Not whether I think they’re wrong about the meaning of life or they think I’m wrong about the meaning of life. I hope.

YOUNG: There’s a lot of need to escape from monotony. Even Heaven is a monotonous place at the end of the day.

VESTAL: It probably comes from having lived in a lot of small towns in the West. Portland is the largest city I’ve lived in, and for a while, it did feel kind of big. I’ve lived in towns of just 2,000 or 3,000; and I remember driving an hour to see Pulp Fiction when it came out. Now I feel like people, when something comes out in the culture, you get it instantly. You see it and you get it. When I was young, you were kind of culturally trapped in a small town.

YOUNG: What’s funny is that no matter where you’re born, you want to get out. I guess there are some people who are very comfortable making their world small and living with monotony. But for any kind of real thinker or creative person, you crave escape.

VESTAL: I think that’s right, and I have an itch that I’ve always had. To get in my car and just drive by myself somewhere listening to my own music. It’s a non-climate friendly desire.

YOUNG: [laughs] That’s very West Coast awareness of you.

VESTAL: [laughs] Actually, when I get home from New York or any city with public transportation, one of the first things I do is come up with an excuse to be in my car. Drive for no reason.

YOUNG: Because you find a sense of peace from it?

VESTAL: I guess so, something about solitude and control.

GODFORSAKEN IDAHO IS OUT NOW.