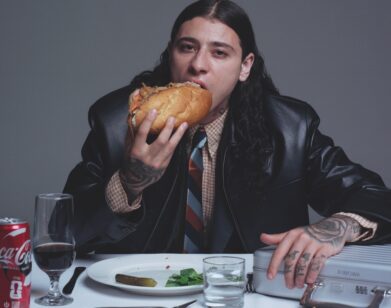

Satirist Sam Lipsyte’s Aura is Showing Some Positive Vibes

Aura reading by Magic Jewelry.

By and large, novelists haven’t managed to get their arms around the mess of the world any better than the rest of us. From the young upstarts to the literary lions, they, too, seem to be holding on for dear life. But perhaps the one writer best equipped to nail contemporary society to the wall is the New York comic satirist Sam Lipsyte. His particular style—wickedly funny, ruthlessly blunt, and uncannily observant, with his smart, hyperactive prose frolicking over the sacred and the profane—is perfectly suited for our maddening, hysterical, and deeply troubled age. We the people need Lipsyte to make sense of us, and the 50-year-old author has delivered with his latest (and fourth) novel, Hark, which concerns a self-styled guru out to change the psychology of a wounded nation with the help of his embattled acolytes. The world captured in Hark is eerily familiar: “The hunters of meaning had found no meaning. The wanters of dreams were dreamless.” Meanwhile, preachers and entertainers are fighting for the hearts and eyeballs of the country “before robots seize the planet for good.” This past October, Lipsyte spoke with the writer Jonathan Ames about comedy, writing without a destination, and the need for answers in dark times.

———

JONATHAN AMES: I wanted to start by asking you, have you read Charles Portis?

SAM LIPSYTE: I love Charles Portis! I’m a big fan of The Dog of the South and Masters of Atlantis. I liked Norwood a lot, too.

AMES: I’ve read all of them recently except for True Grit. Anyway, I bring up Portis because he does something in his writing that I think you also do really well in yours, which is comical, dissonant pairings in a sentence. In Hark, you write, “She was quick to cruel judgment and frequently misplaced jar lids.” I love a line like that.

LIPSYTE: I like to do that kind of playing with scales.

AMES: It works and it’s really funny. I often get asked to talk about comedy in my writing, but the answer is that it’s not necessarily intentional. What about you? Do you create a sentence like that because it amuses you and because you’re hoping to amuse the reader?

LIPSYTE: I want it to be funny and strange and feel fresh. If it feels that way to me, I’m hoping it’s going to feel that way to a reader. I do think it demands different tools to be funny in a book, using language, as opposed to comedy that’s in a performance or stand-up. I admire stand-up comics and I love comic film and television. I think those really rely on nudging the comedy with your body—

AMES: It’s in the eyes. That’s why a live performance of a comedian is so different than a comedy album.

LIPSYTE: I used to listen to a lot of comedy albums when I was a kid. I’d be following along and laughing, getting it, and then there’d be that moment on the album when everyone in the audience is laughing, because the comedian did something onstage that was physical or visual. If you’re listening to the record, you have no idea what it is.

AMES: When I’m writing, I don’t think, “Be funny!” For the most part, it just comes out that way.

LIPSYTE: I think it’s just one’s filter. Some people process the world in a more comedic way—or a more darkly comic way. Some people do it in a more earnest way. It’s just the way the world comes in and goes back out. It’s not, “I’m going to be funny now and later I won’t be!” It’s really about what you think life is about. What’s your stance on existence? That’s really where your tone comes from.

AMES: I like this idea of the filter. For some reason I thought of a colander in a sink, or a noodle maker. What comes out of your filter is like a funny noodle. I’m mixing up a strainer with a noodle maker.

LIPSYTE: Once, in school, I had a special spoon for picking up spaghetti. A spaghetti spoon. Maybe that’s part of it, too?

AMES: I think that would be more about the ingestion of comedy. The second writer I wanted to ask if you’ve read is the American Tibetan-Buddhist Pema Chödrön. A lot of the stuff I’ve been reading in her books is about accepting the world as it is. You never know what’s going to happen next. When we try to hold on to things is when we suffer. Early in your book Hark is the declaration, “I am comfortable with uncertainty.” And I really thought you were quoting Pema Chödrön, who has a book called Comfortable with Uncertainty. But I guess that was just by chance.

LIPSYTE: It’s definitely an idea I’m familiar with, having dipped into various Buddhist ideas. All the forecasting we do in life is a problem, trying to predict exactly what is going to happen and how to control it. I take these ideas that come up in the book seriously. If there’s a satirical part, it’s the way people try to commodify them.

AMES: Was that philosophy one of the reasons for writing the book, to put those lessons out into the world?

LIPSYTE: I’m certainly not qualified to put out a philosophy that could help people. But I, like a lot of people, am always wrestling with ideas and impulses, both good and bad. One of the things that inspired me was just watching so many people, especially in increasingly dark times, grasping around for a way to think about their lives. These are people looking for a space for themselves and a little peace, really, and to be part of a community. I knew I couldn’t tackle that with a straightforward approach. It was going to come out as a strange comic novel. And there were people close to me, looking into different kinds of yoga practices and mindfulness and Buddhism and whatever else they could find that would help them in their search. I became intrigued with that experience, looking for some kind of answer once you realize that the answers being given to you by the culture and the major political groups in our country are ridiculous.

AMES: I really do think my reading of Buddhist texts has helped me to see that the painful things are the things I can most learn from. To sort of strengthen myself. Did you start this book in the [Barack] Obama years or during the [Donald] Trump presidency?

LIPSYTE: I started it in 2012 with this notion of mental archery and people seeking some kind of spiritual solace. The other elements grew out of that. So, yes, I started it in a different era, and there are six years’ worth of layers in the result.

AMES: When did you finish the book?

LIPSYTE: I finished it this morning. [Laughs] I was still putting in commas on the final pass. But to answer your earlier question, there was no moment right after Trump was elected when I thought, “I’ve got to rewrite this book now.” There are always dark times. When I published my last novel, The Ask, in 2010, people kept asking, “Did you see the financial crash coming?” I didn’t. I just always assume that things are going to shed. If you write that way you’ll probably be correct.

AMES: It can seem daunting to write a book that takes years to finish and still somehow talk about fads or trends or even technology. With everything changing so quickly, does that become an issue for you?

LIPSYTE: I try to keep things vague enough so that the same cell phone can be used in 2012 and 2018. I wrote a book in 2000 that ended with this kind of reality television show and I remember my editor said, “This is just a fad. There aren’t going to be reality television shows next year.” But I guess you can sense when something might go on long enough to have some meaning. I do try to avoid details that nail the time so precisely that a reader would think, “Oh, that’s so 2015.”

AMES: You have a great depiction of marriage in Hark. You are married with two children, so I was wondering how your wife reacts to your depiction of marriage—because you do mine marriage for comedy, and one of the threads in your writing seems to be disconnection and frustration.

LIPSYTE: I think she’s a little fed up with it. She’s been very understanding for many years, but sometimes I think I push it a little too far.

AMES: I was once writing a novel and, though I wasn’t married, I was with a girlfriend who didn’t like me writing about sex or scatology. So I didn’t. Then I was two-thirds of the way through the novel and the relationship ended so I suddenly wrote a sex scene where the male character had gas. I was thinking, “Shoot, now I’ve got to put it all in one scene because the book was so clean for the first two-thirds.”

LIPSYTE: Now you can let it rip, as it were.

AMES: Do you censor yourself at all, thinking of your family?

LIPSYTE: No, that’s the thing. My wife knows I can’t do that and that’s why she’s so understanding. But I know that sometimes it irks her because she has to spend time with her friends saying, “Well, that’s not us.” Or, “That didn’t happen.” I’m sure that’s annoying. And just today a dean at Columbia, where I work, said to me, “I’m reading one of your books. I can’t believe that you think that because you seem like such a sweet guy.” And I had to say, “Well, it’s not me, it’s a character.”

AMES: Is that confusion scary to you?

LIPSYTE: When you write fiction and do it in a way that I think is compelling, you make yourself vulnerable. It’s not that people are going to find out some stuff that you did in your past. It’s really more that they get to see your filter in its intricate workings. They get to see how you think and how you process the world and the weird ways you apprehend it and that makes you very vulnerable. So, it’s a strange feeling but it’s one that, if you write, you live with.

AMES: I think it’s why, in my own work, I’ve started using myself more and more as a character because when I wrote fiction, everyone would say, “Why didn’t you call that a memoir?” And then when I wrote non-fiction they were like, “Oh, you made that up.” Then I started writing fiction with myself as a character to completely confuse everyone and myself. Here’s another sentence from your novel that I really admired: “Fraz berates himself for foolish speculation, then berates his inner berater for stifling winsome or playful thoughts, for from such lazy perambulations through the noggin’s grottos profundity can effloresce—ideation’s lush, dark bloom.” Suddenly I’m seeing the world effloresce. I don’t know that I’ve ever seen that before, and then “ideation’s lush, dark bloom.” How do you write a sentence like that? Isn’t Vivian Darkbloom the anagram for Vladimir Nabokov?

LIPSYTE: Oh, that’s interesting. I’ve been channeling Nabokov without even knowing it! But yeah, it takes several drafts to get the syntax exactly right. It’s like working on a piece of music. You’re thinking about every note and every space between the notes.

AMES: I feel the care in your sentences—there’s a sustained musicality.

LIPSYTE: Thank you. I hope readers slow down and enjoy the language and characters and the interplay. In terms of sheer plot, I’m not going to promise the most intricate fast-paced thriller—not to say that stuff doesn’t happen, a lot of stuff happens.

AMES: I’m always intrigued by the genre of the thriller and how to write something that compels someone to turn the page. There are always the old twists, the unexpected, “What? I didn’t see that coming.” If you can pull that off….

LIPSYTE: I think most of us read for how something is going to happen more than what it going to happen. What’s it going to sound like? What’s it going to feel like? Not what the thing itself is going to be? Is he going to die or not die? Is he going to catch the person or not catch the person? You ultimately don’t give a shit compared to what it’s going to feel like when this thing is described.

AMES: I think that’s been a problem with my recent writing. I write things in my mind, or I figure it out in my mind, and I get it so figured out that I’m too bored to put it down on paper.

LIPSYTE: That’s why I don’t do that. If I start to write it in my mind I stop. It’s like masturbating before your lover comes over or something. If you’ve already got it mapped out, you’re not discovering as you go. It becomes grunt work and who wants to do that? It goes back to the Buddhist idea of being comfortable with uncertainty. In the compositional moment of writing, one wants that uncertainty, at least for a first draft. Later on, the critical mind can take over and really think things through. But in the beginning, since you don’t know what’s going to happen when you leave your house in the morning, why know exactly what’s going to happen when you start writing an idea?

AMES: That’s true. I’m going to work on that. Thank you.

LIPSYTE: Just try some mental archery and you’ll be fine.

AMES: Just to bring in politics for a moment, sadly—and the place of the writer in the American culture. I realize that you and I are both in our fifties, and pardon me, I’m permanently immature, but I’m thinking, “Why isn’t an elder statesman like Don DeLillo writing an op-ed? Or Joan Didion? Or Thomas Pynchon?” I feel like in previous generations, Norman Mailer or Gore Vidal or Susan Sontag or Kurt Vonnegut or somebody would be representing the writers confronting corruption and what’s going on in the U.S. What do you think of the writer’s place in the year 2018?

LIPSYTE: I always put it this way: There was a time when the big movie came out, the big record came out, the big book came out. People of a certain type, if they weren’t going to actually read the book or see the movie or listen to the record, still had to pretend when they attended the cocktail party. They still do that, but not with the book anymore. Nobody has to pretend to have read a book anymore. In a way, I think that we’re off in the margins a little more. But that can be a good thing because that means we’re not being asked to prop up anything that feels too central and compromised. We can work from the outside. But the question is, too, are they asking Don DeLillo to write the op-ed anymore? I mean, is it that he’s not writing it or that nobody is asking him to write it? I don’t know the answer. Those are all white writers you mentioned. Maybe we’re moving past just asking a certain kind of writer to comment on society, and, in an age when identity is so important, maybe lots of different people are being asked to represent different groups in the public conversation.

AMES: Everything you’ve just said is interesting. For one, that we’ve even lost the pretend readers now. Then, also, using your archery and turning the negative into a positive that operating out on the margins is a good thing. But I’m still someone whose main cultural consumption is the novel. I feel like Toni Morrison could write a great takedown of Trump that could rally a nation. I suppose I’m revealing that I’m not pro-Trump, which is not unexpected.

LIPSYTE: But it would really rally half a nation because half wouldn’t read it or even know to read it. It reminds me of something I once read that the screenwriter Robert Towne said. He was talking about the golden era of 1970s movies. He was saying, before the 1970s, everyone was agreed on this idea that America was really great. Then, after Watergate and Vietnam, everyone saw America as this corrupt, broken, fucked-up place. That’s where you get the great paranoid movies of the ’70s. Then he said, after that, there was no collective agreement on anything. Everything became much more fractured and niched out. So you’re never going to have that moment where we’re all basically on the same page about something.

AMES: Well, I think we covered all my questions. You know, the only other interview I’ve done for Interview was seven or eight years ago when I interviewed Floyd Mayweather. So it’s you and Mayweather.

LIPSYTE: Do you want to ask me a question that you asked Floyd Mayweather?

AMES: God, I’m trying to remember what I asked him.

LIPSYTE: You don’t have to ask me a question. I’ll just tell you I feel I can take anyone in my division.

———