let's talk about sex

Playgirl Magazine Is Back, and It’s Not What You Think

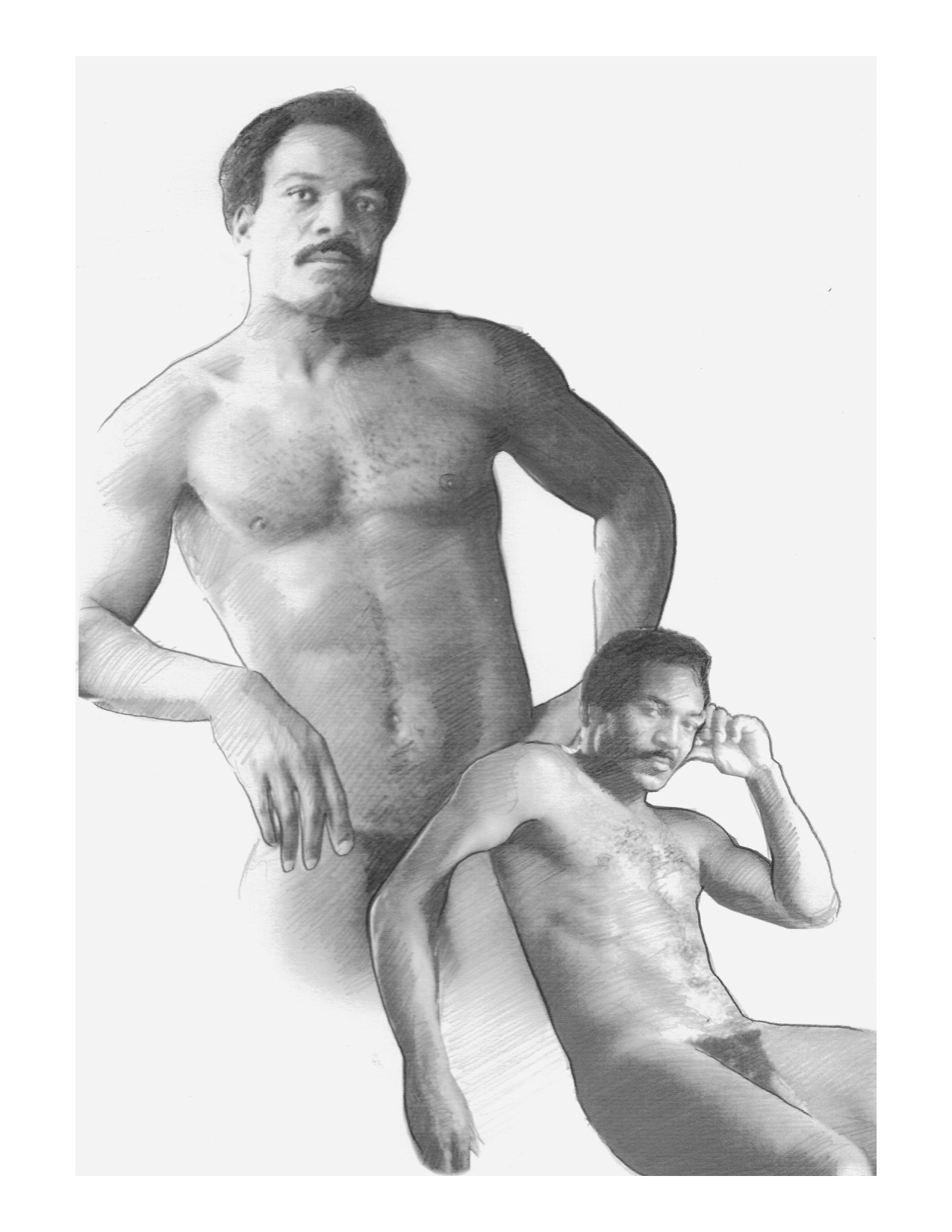

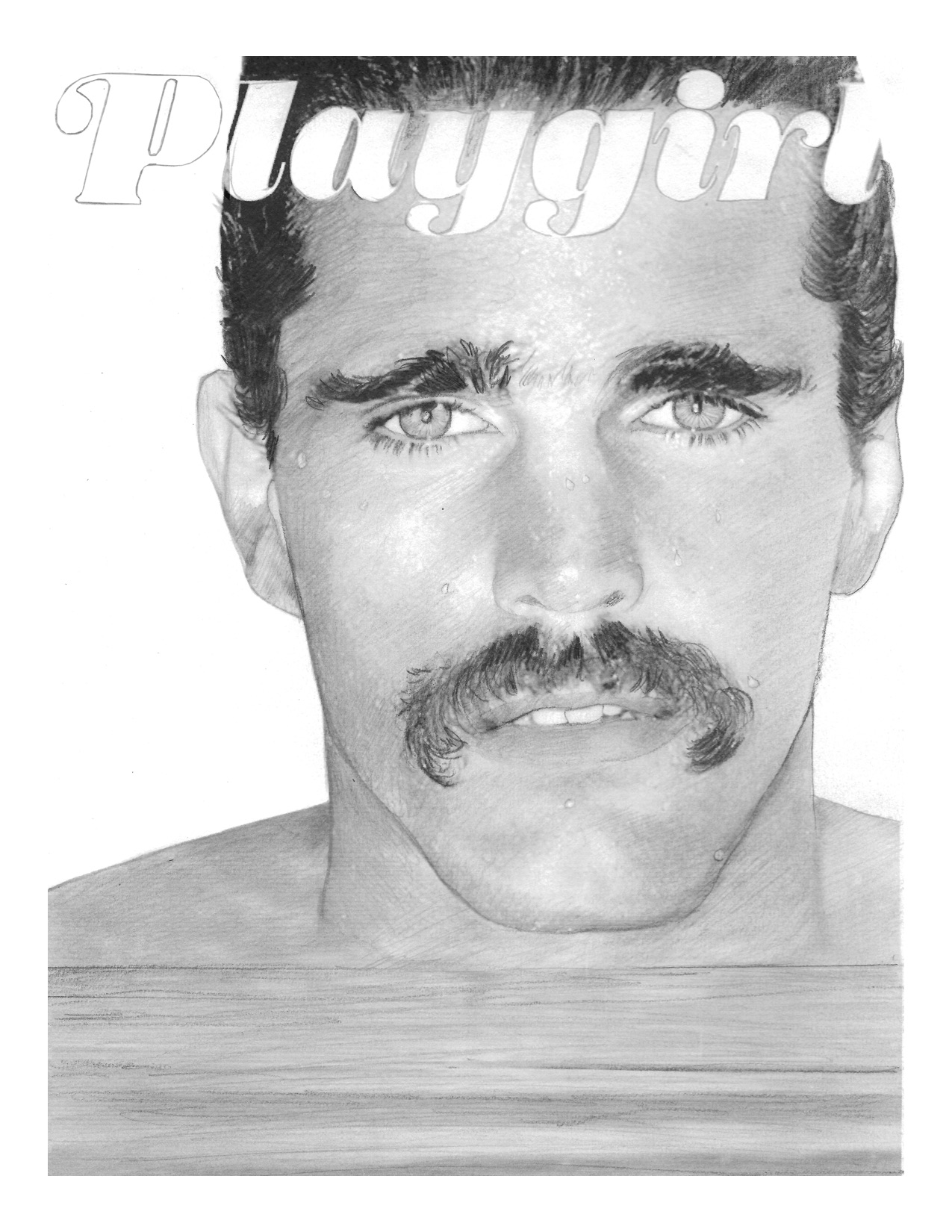

Playgirl, April 1977.

The streets that slope down from the Colosseum are crammed with souvenir shops, their contents spilling with shiny toy relics of Rome’s past. Shelves are toppled with tin gladiator helmets, enamel plates etched with the cityscape are glued to walls like stamps, and replica figurines of Michelangelo masterpieces are aplenty. With their tufted abs and manhood scaled to the size of a peanut M&M, these miniature macho men carved in the likeness of ancient heroes like Hadrian and David are mass-produced manifestations of male idealism. And for 10 euros a pop, their sex appeal is a palpable, accessible thrill. It was the image of these pint-sized Adonises, which I encountered regularly while on a Roman holiday last summer, that immediately came to mind when I heard about the relaunch of Playgirl Magazine.

The title, which dates back to 1973, has a scantily clad history of putting the male form on full display. While its medium was paper, not plaster, like the statues, the magazine was, in its simplest form, a means of distributing an ideal vision of the male body to the masses. From 1973 to 2016, when the magazine folded, the definition and shape of masculinity have evolved tremendously. Tourists, whether traveling to Rome or to Ancient Babylon, can always count on a currency of well-groomed trophies at gift shops, but what can readers expect from an iteration of Playgirl in 2020? For one, it’s not what you think. The title’s new publisher, Jack Lindley Kuhns, will unveil a modern mold for the traditionally nudie magazine this month—a mold that looks beyond a simple state of undress. Sure, the infamous centerfold will make its comeback, but in a far more decadent way. Nudity will, of course, be a focal point, but the relaunch will also make way for thought leaders of our era, much like Playgirl once attracted contributors like Eve Babitz and Maya Angelou. Yes, you read Angelou right.

Like a newly polished mass of marble in a hall of chiseled hunks, the rebirth of Playgirl will not reinvent the wheel. It will, however, cast a new light on a publication that has long lived in the shadows. Its reveal will shock some, delight others, and on newsstands, be exhibited like a rarified jewel more than a disposable glossy. Ahead of the debut, Silvia Prada, the artist and Playgirl’s Image Director, pays homage to the magazine’s legacy with a series of exclusive illustrations and a trove of stories she and Kuhns shared from the publication’s naked archives.

———

MITCHELL NUGENT: What’s your purpose for relaunching Playgirl Magazine?

JACK LINDLEY-KUHNS: When I was introduced to Playgirl, I didn’t really know anything about it. I think that’s what attracted and inspired me to pursue this as a concept—taking something that was [once] great and turned ugly in a way. I think one of the best things about Playgirl is it can be interpreted in so many different ways, whether starting from entertainment for women; to moving into the ’80s; and the ’90s that were so celebrity-focused; and then it turns into porn. I knew when I saw the early years how relevant it could be today.

NUGENT: What is it like bringing back a magazine with a near 50-year history?

KUHNS: On the most important end, it’s an honor. It’s very daunting, but I think that I always knew that if this publication was done in the right way, it could mean a lot.

NUGENT: Is there a particular era or iteration of the magazine that you take inspiration from in this new edition?

KUHNS: I think that when I look at the ’70s, the centerfolds look like paintings. It’s just so innocent, even though it [features] full-blown nudity. And it had contributors like Maya Angelou, which when I saw that I was like, “What the fuck?” Then I grabbed another issue, because I was just trying to get through all of them [Laughs].

NUGENT: Silvia, your art evokes an aesthetic that I think lends perfectly to the history of Playgirl. What was it like digging in the archives?

SILVIA PRADA: Absolutely a dream. Playgirl, especially during the genesis in the seventies and in the eighties, was part of the way I grew up as a teenager, and how I understood pop culture. My fascination with the male image and the historical construction of the male image and its memory is my subject of work.

NUGENT: Were there any particular archival moments that got your heart racing?

PRADA: Of course. I was collecting the magazine and knew most of my favorite issues. But when I got all their archives, they make me almost speechless because of the level of refinement and all the artists collaborating, from illustrators to photographers. The casting direction for me was the most impeccable. The message is pure.

NUGENT: Playgirl has historically been a publication positioned toward female readers. Will the new edition be the same?

KUHNS: It was very clear that the first era was entertainment for women, and it wasn’t just entertainment for women in a sense of “here’s men naked.” That was a part of it, of course, but the biggest thing that I fell in love with about Playgirl was that there were so many sections within it—whether it’s illustrations or politics, nudity or fashion. There’s so many profound themes that it’s kind of stupid that this magazine hasn’t been done right in a long time, because there’s just so much to work with.

NUGENT: Silvia, what about Playgirl’s legacy is most striking to you as a woman, and a queer woman at that?

PRADA: For me, it represents an open message that eroticism has no gender right now, and no sexual tendency, and Playgirl is pure eroticism on paper to take home. It’s a fantasy. The magazine was focused on the idea of desire, but desire in every topic they touch—in the environment, health, politics. It’s a magazine about desire. And at the time, it represented a specific moment in history in which the prototypes of men or women are not confronted and they are merged in the idea of utopia and freedom. For me, Playgirl never showed the male image or female in a prototypical way. It was always very fluid and an escape from the established rules of that time.

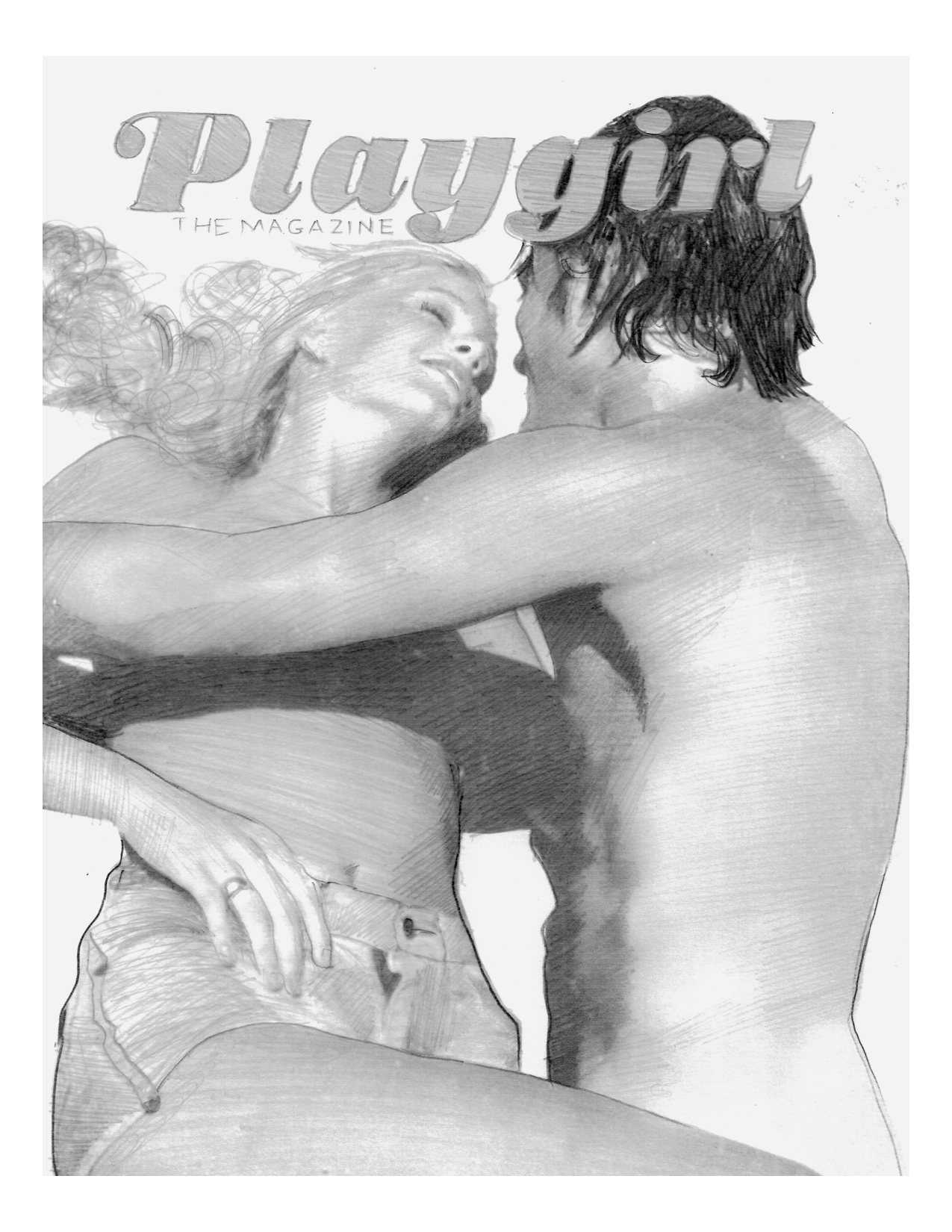

- October 1973.

- October 1974.

NUGENT: Jack, do you have any dream female contributors for this new era?

KUHNS: I wrote one name down: Michelle Obama. Michelle Obama. Michelle Obama.

NUGENT: Why is a magazine like Playgirl needed today for female readers?

PRADA: I think it’s a moment to make a bigger statement about gender and a bigger statement about eroticism and culture in general. I think that we are living in difficult times right now, but they’re inspiring times to open this much-needed conversation about redefining femininity and masculinity. From the erotic and the desire perspective, there’s nothing more feminine than defining a new era of decision.

NUGENT: The magazine’s archive is chock-full of editorial tentpoles like the iconic centerfolds, “Man of the Year,” “Campus Hunks,” and “Real Men”—can we expect any revivals?

PRADA: The age of the centerfold, it’s a unique time and story. It was just very unrepeatable in history, not only because of the moment of liberation of women it was a moment also to find a new paradigm of masculinity and through the female eye.

KUHNS: The word “centerfold”—I was very adamant about having that in the publication. I think that working with the people that I’ve been working with…their whole concept was that nudity is kind of fluid throughout. And for me, if there is anything that is known or iconic about the magazine, it is a centerfold, but]I think that centerfold can be expressed in different ways. In regards to “Campus Hunks” and “Men of the Year, I think those are very dated. I think that they were intentional during the ’70s and ’80s, but today just seem a bit archaic. I think that the biggest theme that I can come out of issue one is entertainment for women.

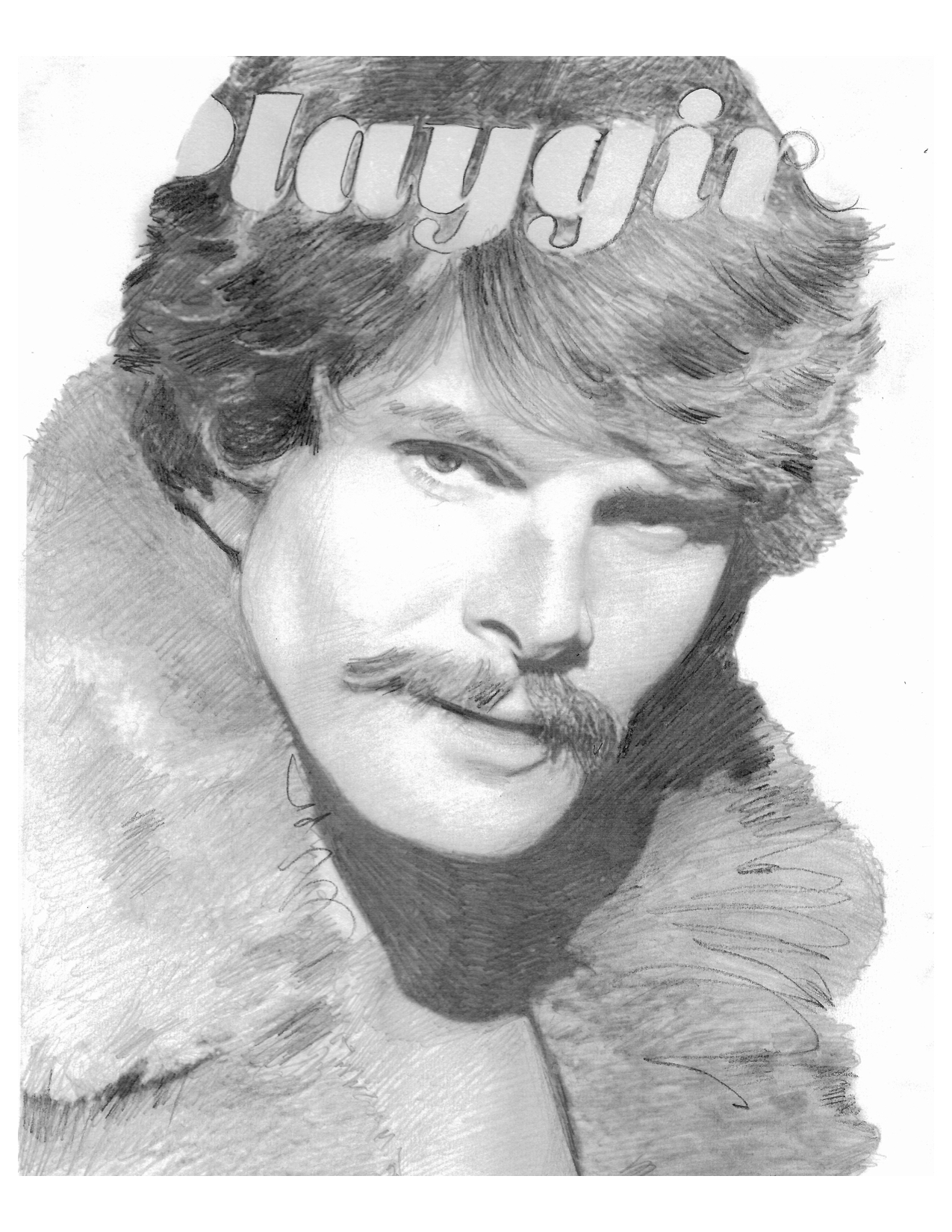

January 1977.

NUGENT: Playgirl has, historically, also had a large queer readership. What do you think your queer friends and peers will be most excited about in this new era?

PRADA: I think for many of us, I mean, you and me, all my inner circle, we have a great historical memory. We are living in this era of nostalgia. And we live in a kind of a cultural menopause where in visual terms, we are needing something like neat creation. Because we are consuming the same things all the time, I think we choose certain visual references in an effort to educate the present and find a new meaning for it. Playgirl was a magazine for women that became iconic for gay culture. And gay culture has always been transgressive and progressive and has this proximity to feminine nuances. It will always be avant-garde.

NUGENT: What will be the emphasis of nudity in the new edition?

KUHNS: I think the issues in the ’70s were so innocent. This magazine has been redefined so many different times, but it’s really about just making it the most inclusive publication that we can. I think it gives people an opportunity to step back and think about what Playgirl really means. Does it mean naked men? Does it mean feminism? Does it mean porn? There’s a lot of different ways that people can interpret Playgirl, and I’ve known this because people have laughed in my face when I’ve told them what I do, and [other] people have said, “Wow, that’s really cool what you’re doing.” So yeah, nudity will always be a part of Playgirl. It’s just about doing it the right way.

Playgirl’s relaunch issue will debut on Monday, October 26.

———

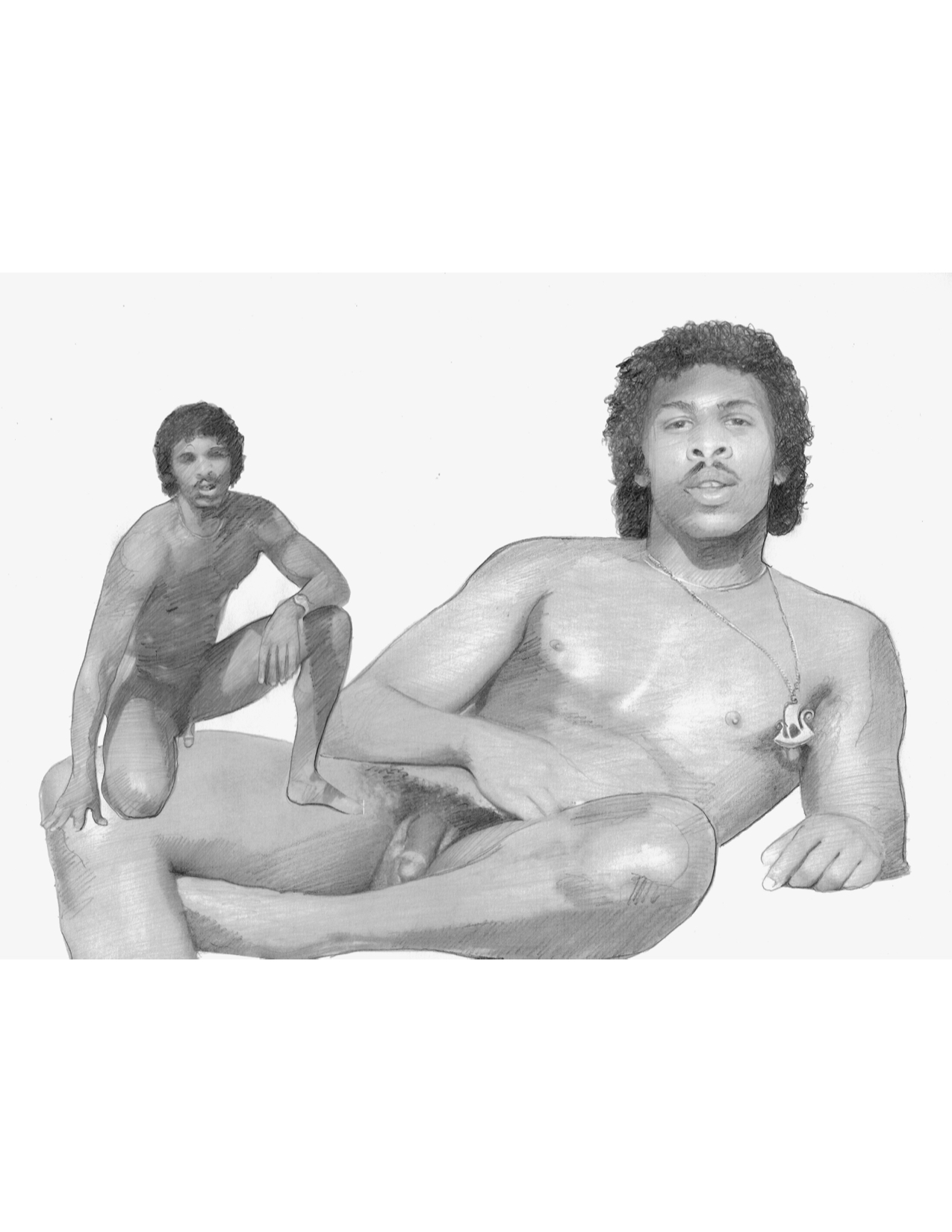

October 1976.