The Weird World of Noel Fielding

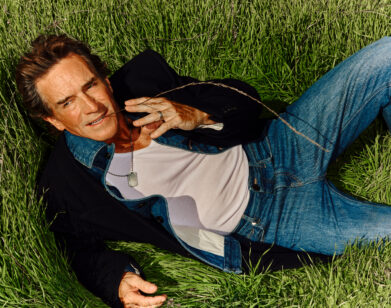

NOEL FIELDING IN NEW YORK, JANUARY 2016. PHOTOS: VICTORIA STEVENS. GROOMING: NATE ROSENKRANZ/ HONEY ARTISTS USING ALTERNA HAIR CARE.

To truly appreciate Noel Fielding’s comedy, you must allow yourself to get drawn into his world. It’s a pretty surreal place, where anything—from gorillas to inanimate objects—can be a character, and characters are expressed through multiple mediums including music and visuals. After nearly two decades on stage, however, the British actor, artist, and comedian knows how to engage his audience. It’s not just about his charisma—though with his signature coiffe, eyeliner, and mod clothing, he is quite charming. It’s also about structure. Even if it seems like Fielding goes off on random tangents onstage, by the time he tours a show, he’s established a carefully constructed journey of augmenting oddness. “It’s getting the balance right so that they’re going, ‘Oh my god, how did we get here?’ Or they’re laughing because they trust you by that point,” he explains.

“I have a bit in my show where I play a half-man, half-chicken,” Fielding says of his current act, An Evening with Noel Fielding. “I can’t start with that because people would just be like, ‘What’s happening?” he continues. “I do some stuff that’s more accessible, and then I gradually start doing a bit more weird stuff, and then I do this long piece about teabags where I play a bunch of different teabags in a cupboard. By the end, it gets to this bit where my wife’s having an affair with a triangle and where I play a half-man, half-chicken.”

In the U.K., Fielding is a well-known entity. In the U.S., where he’ll be touring An Evening this month, he’s more of a cult figure. There are those who know him from The Mighty Boosh (2003-2007), his show with his frequent writing partner Julian Barrett, and others who think of him as Richmond, the goth from The IT Crowd (2006-2013). But Fielding’s work extends past the stage and screen. A graduate of Croydon Art College, the 42-year-old has published a book of his artwork (Scribblings of a Madcap Shambleton, Canongate UK, 2012) and exhibited at the likes of the Saatchi Gallery and the Royal Albert Hall.

Here, we discuss Fielding’s entry into comedy in the late 1990s and the evolution of The Mighty Boosh.

EMMA BROWN: What did you want to be when you were five years old?

NOEL FIELDING: [laughs] When I was five? A cowboy. I used to wear this cowboy outfit. I wouldn’t take off. It was ridiculous. My mum was like, “You’ve got to take that off sometime,” and I was like, “No way, this is it.” It was the ’70s—it was turquoise and yellow, really psychedelic colors. I wanted to be a psychedelic cowboy. Or a zookeeper—that’s why we ended up doing the first series [of The Mighty Boosh]. Or a painter. When I was three or four, I was really good at drawing and painting, and everyone used to say, “You’re going to go to art college.” I didn’t really know what that meant. When you’re a kid and someone’s an artist, you think of Leonardo da Vinci. You don’t think that’s a job; you just think of a man with a beard painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

BROWN: Do you come from a creative family?

FIELDING: A funny family. My mum and dad are both really funny. My granddad’s really funny, my uncle’s really funny, everyone’s really funny. You have to be quick, otherwise you get roasted. Everyone takes the piss quite a lot. You have to be really sharp.

BROWN: Did you have imaginary friends as a child?

FIELDING: There was a big age difference between me and my brothers—about 10 years—so I was an only child for a long time. I used to hang out a lot on my own. I played a lot of weird games with a lot of imaginary people. I guess it’s kind of roleplaying, isn’t it? I had a cat called Jethro who had one eye, and I used to hang out with my cat quite a lot. When I was a really young child, I felt like I could see fairies. I was convinced there were fairies in my grandmother’s garden.

BROWN: Were they traditional fairies—little girls with flower hats?

FIELDING: Not just women, men in little green jackets. They were moving really fast, like birds almost, like tiny creatures. I don’t know what that was about. When you’re quite young, your imagination’s quite free.

BROWN: I wanted to talk about the beginning of your career. You won the Edinburgh Comedy Award for Best Newcomer at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 1998.

FIELDING: With Julian [Barratt]? Yeah. I did a standup competition earlier, in 1996 or something, and I got to the final. Frankie Boyle won it and I came in second. It was the first thing I did. Then the year after I did a standup show with Frankie Boyle and a few other people—Chris Addison, who directs Veep and was in The Thick of It. We had the same agents who said, “Why don’t you just do a half hour of standup each, rather than writing a whole hour of standup?” But then we got together and I said, “This would be quite good if we just do a crazy show. I don’t really want to do a half hour of standup.” And he was like, “No, nor do I.” Then we started writing a song about a mammoth and we were thinking it would be quite funny if we could make a smoothie on stage and if we got a girl to cry into it and drank it and fell in love with her. Then we thought it’d be good if we were in a zoo playing zookeepers, and we had an idea for this boss who sucks us through his eyes into this magic forest, and that became Rich Fulcher’s part. Rich wasn’t around when we were writing it, so we just told him we wanted to do a boss at a zoo called Bob Fossil—”You’re going to suck us into this magic forest”—and he sort of improvised it all.

The Boosh did well straight away. There was nothing quite like it. [Flight of the] Conchords do that kind of stuff now, but at that point… When we were just doing comedy, we did a rap song because we were into the Beastie Boys and Beck and hip-hop and stuff like Kool Keith. We wanted to do a rap song. We thought it’d be quite good if this zookeeper that Julian always talks about—his hero is a zookeeper that went missing—appears at the end. He disappeared and then Julian built him up as this amazing guy. And then there’s this character, a jazz-fusion guitarist in the forest, and he has a big afro with a door in it and he opens it and the zookeeper is inside his afro. He’s called Tommy and does a drum and bass rap. [laughs] That was the extent of our first show. But it was different, no one was doing stuff like that at the time. I think being in bands—I’ve been in bands—you’re not coming from a comedian’s point of view. I’ve done painting and Julian was into music. We just found the idea of standup a little bit limiting.

BROWN: When you came in second in the 1996 competition, what was your material?

FIELDING: That was me on my own. It was a long time ago. It would’ve probably been some stuff about having a starfish as a pet from my parents. All my friends got dogs and cats for Christmas, and I got a starfish called Roy. I used to take him down to the park on a lead. It was a weird, long, rambling story. There was some other stuff about chimpanzees—another weird, long, rambling story. And another thing where my dad was a hammerhead shark. I can’t even remember what these jokes were but they were very surreal. If the audience went for it, it went really well. If they didn’t get on board it was difficult.

BROWN: What was the split? Was the audience generally on board?

FIELDING: When you start, it’s not to do with the material so much. It’s more to do with how you can control a crowd and make friends with an audience and sell your brand of humor. When you’re new, you’re not really good at that yet. You haven’t really got the stage skills to sell bad material. They either go for it or they don’t. You’re a bit stranded if they don’t. I think I had a really good semifinal then at the final, I wasn’t too good because I’d been up all night worrying about it.

BROWN: Have you died recently on stage?

FIELDING: [laughs] No. Maybe in America this is different, but you don’t really die once you’ve been doing it two or three years. If you’re going to be a good standup, or a successful standup, or a standup who can work for money, you have to eliminate the possibility of dying quickly. If you still are dying three or four years in, maybe you should be a writer or an actor, maybe it’s not going to be the thing for you. I learned that quite quickly—I could get an audience into my world and if you can do that, they’ll go with you not all the way, but a lot of the way. [laughs]

BROWN: What’s the London comedy scene like? You seem to know everyone.

FIELDING: I think I just know everyone because I’ve been doing it so long. In comedy, you see yourself as a newcomer and then you realize you’ve been doing it for 18, 20 years, which is ridiculous. But I don’t really do gigs in London very often. When The Boosh was big it was impossible because if I did a small club it would sell out to just fans. I’d have to do unannounced gigs because your fans will laugh at everything because they know what you do already. What you really want is a neutral audience that isn’t too harsh—a good comedy crowd—but that don’t know necessarily what you’re doing. It’s very difficult once you’ve been on telly because people know what you do. They give you a little bit of grace but then they’re harsher if you’re not funny, so you have to be funny. Whereas you’re sort of a cheeky surprise when you’re unknown. Me and Julian always felt like if you take yourself off somewhere private and make stuff and then bring it out, it’s the best way because you’re not influenced by the scene and the circuit. There’s these weird little pockets—it’s like school, the comedy circuit. There’s people who are annoying, people who are bitter, people who are really nice, people who are friendly, new people, people who have been doing it forever. It’s a bit like that in Edinburgh [at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival] as well, it’s a bit cliquey and we always tried to separate ourselves from that. Also we decided instead of going around to different clubs all the time we would just do a residency in one place.

BROWN: Where did you do the residency?

FIELDING: In Highbury in this place called The Hen & Chickens, which was a little tiny theater above a pub—it held about 58 seats. We did it every Monday, which was a graveyard slot, but we worked out quite quickly that all our friends who had been out on the weekends liked watching something mellow [on Monday evenings]. We used to do an hour or so. We’d do cabaret stuff in the beginning—have a few of our mates on and musical stuff—and then have a break and then do the show we were going to take to Edinburgh in whatever state it was in, add a new 10 minutes every week or a new 15 minutes. That was how we’d do our shows. We did that for three years and that’s how we learned to try weird stuff. You couldn’t have done it in the confines of a comedy club because there would’ve been standups before you. We did a character where we had a tiny horse on a record player spinning around, a lot of weird shit that was visual, musical, that there’s no way you could’ve done between two standups.

We did do this one place, which is a proper comedy club. We didn’t even have a name at that point, so people would come in and say, “Those two guys are going to be on? The ones who call themselves Lego Wolves?” or whatever we called ourselves. We’d go on after the interval so if we were supposed to be in a forest we’d put loads of fake plants and trees everywhere, and we’d have a big boombox and weird sounds like a forest. We just did 10 minutes of us lost in the forest —a double act thing. And again, that was the basis of our first Edinburgh show.

I guess really what we were doing was looking for a way of doing comedy that wasn’t standup, that was theatrical and musical and visual, and a double act. Also Rich Fulcher was in it, so we had two English, mumbling, quiet people and then a quite brash American. It was quite the contrast. Eventually we added my brother who played the shaman, and then we added Bollo the Gorilla. We had a team: Dave [Brown] was really good at dancing and [my brother] Mike [Fielding] was really deadpan, Rich had a lot of energy, and me and Julian were the double act. We had a lot of skills in that little group so we were good at making shows. We evolved it really slowly and we toured it a little bit, we did radio shows, we did TV shows, we did big tours, we did a festival. The only thing we didn’t do is a film really, which hopefully one day we will.

BROWN: Have you had any surprising Boosh fans?

FIELDING: America was quite weird. It got really big in England really quickly, and it was kind of scary. We went on tour, and the first day we went on tour in York we tried to come outside the venue and there were 500 people outside. They were screaming and dressed up like characters from our show and they chased us to the hotel. My tourmate was Australian and he went, “Shit, what have you done? This is like The Beatles mate. You’re fucked.” We didn’t have a clue, it took us by surprise; we didn’t know anyone was watching. It quickly expanded until we were doing arenas and playing 10,000-seat venues. We’d do book signings and they’d camp out overnight and we’d have 7,000 people trying to get in… It was ridiculous. Then we came here [to the U.S.] and the fans here were much more hardcore, they had tattoos of Old Greg, Howard Moon, and Julian. People had driven from all over the country to come to these shows we did at the Roxy and the Bowery in New York. People drove from everywhere and got flights—they were much more serious, in a way. But then when I did Australia recently, they were nuts. They probably liked it even more than the English people. They loved The Boosh straight away, instantly. We’ve got a cult following here but I don’t know how this tour will go at all, which is quite exciting because you’re not in that position anymore—you used to be in that position when you started out.

BROWN: Where are you going on this tour?

FIELDING: We’re doing Boston and New York and Chicago and Portland and Seattle and Vancouver. Toronto, L.A., San Francisco—all the usual places. I don’t think we’re doing anywhere like Kansas. We’re not doing the deep South. We’re doing hipster towns, I guess, and they’re not massive venues. When we first came here as The Boosh, we’d done everything we could do in England so were ready to storm America. “We’re coming, The Boosh is coming!” It was really exciting, and we met Jack Black and Ben Stiller and Mike Myers and Trey Parker—like opening the door, and Mike Myers is like, “Let’s write a film,” and Robin Williams is coming to the gig and talking about the crack fox. We were quite overwhelmed. We were thinking of moving here and trying to do TV show but we had just done 12, 15 years in England and Julian had just had kids, so maybe it wasn’t the right timing. I always had a little bit of a regret about that. I always wanted to travel around and see lots of America, I’d never been to Boston, I’d never been to San Francisco even, so I’m quite excited to just go the places.

BROWN: Have there been any comedians that have come up to you and cited The Boosh as an influence?

FIELDING: [laughs] Yeah, there were loads. It’s manifested in other places, which is weird. Like the guy who makes Regular Show, he’s constantly citing us as a massive influence. I know the guys who did Spongebob were massive fans of The Boosh and they got Rich to do a voice. I see our influence in a lot of weird places, like films and animation and kid’s TV, and not necessarily other comedians. I guess it wasn’t really like comedy; it has more in common with Adventure Time or Regular Show than it has with a sitcom like Two and a Half Men. We’re light years away from that. We don’t own weirdness, we don’t own that style of stuff, but we got there first. It made it difficult for people with a similar sensibility to break through without people saying, “It’s a bit like The Boosh, what you’re doing.”

There was always this comparison between us and [Flight of] the Conchords, which I liked, because I really liked them. We’re friends with them. They started in music—we [went] from comedy to music, and they were music to comedy. I always thought it’d be quite fun to do a film with them, two double acts against each other in some sort of competition. There are a lot of young kids coming through who are a bit weird now. I think Russell Brand was quite a big influence on standup in England, Simon Amstell. I remember being really influenced by Eddie Izzard and Harry Hill and Stewart Lee and Monty Python, The Goon Show, Spike Milligan. You have to have people that you love and you try to be a bit like them, and then you find your own style from that. I was quite a bit like Eddie Izzard when I started, maybe more surreal. It’s always weird when kids go, “I love your standup, I try to do stuff like you.” I think, “Really? I don’t really know what I’m doing. How can you be copying me? I have no idea what’s happening.”

NOEL FIELDING’S U.S. TOUR, AN EVENING WITH NOEL FIELDING, BEGINS MARCH 10 IN BOSTON. HE WILL PLAY SIX SHOWS IN NEW YORK AT THE GRAMERCY THEATRE FROM MARCH 14 TO 19. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT FIELDING’S WEBSITE.