New Again: United States Olympic Special

The 2016 Summer Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro begin tomorrow, with the opening ceremony airing at 7 PM EST on NBC. While these kinds of mega events rarely go off without a hitch, Rio has been especially troubled: serious pollution, corruption in the Brazilian government, the Zika virus, and a doping scandal are just some of the myriad of issues and controversies plaguing this year’s Olympics.

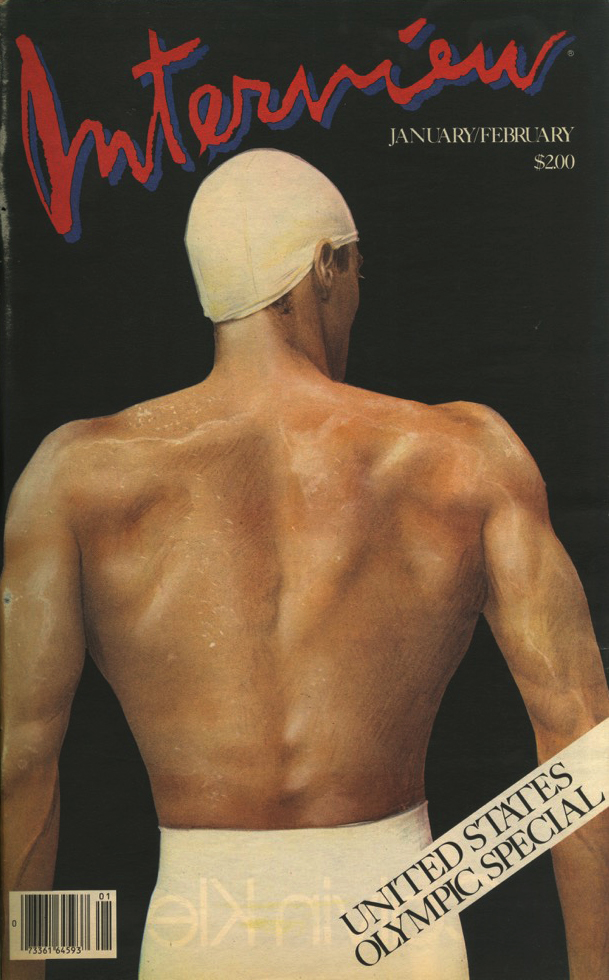

Allow us to turn back the clock to 1984, when Interview dedicated its January/February issue to the U.S. Olympians competing in the Summer Games in Los Angeles. The greener pastures of yesteryear included frank discussion about the disparate treatment of white and black athletes, the use of steroids, and whether or not Russia and their Eastern Bloc allies would even show up to compete. The controversies surrounding the Games, however, do not reflect the remarkable talent and perseverance of the athletes that compete in them. In fact, the issues only make these qualities all the more commendable.

Below are four of the interviews from the 1984 issue, including Mark Caso, a gymnast who broke his neck only to recover and make the U.S. National team; Carl Lewis, one of the greatest track and field athletes to ever live; Evelyn Ashford, the highly decorated track and field athlete who made as much noise with her curt attitude as she did with her blistering natural abilities; and Jack Kelly, a retired Olympian (and brother of Grace Kelly) who helped run that year’s Games. —Ethan Sapienza

Mark Caso, Gymnastics

by Ali MacGraw

In January of 1980, a shock waved jolted the world of gymnastics when Mark Caso, UCLA freshman, broke his neck and was paralyzed during a training session for the Olympic trials. This shattering injury would have halted most athletes’ careers, but for Mark the odds against him became an irresistible challenge and after an astonishing seven-month recovery, he was back on the mats, pushing himself harder than ever towards the perfect routine. In 1981, he made the U.S. National Team for the first time and in 1983, left the Pan Am Games with three medals around his neck—a phenomenon among his peers. Today, his goal is to pass the Olympic trials in May and make the U.S. team, completing the circle he began before his accident.

Mark Caso and I met for coffee on the Friday morning after Thanksgiving, he on his way to a six-hour training at UCLA, I recovering from cooking for and feeding 36 people on a predictably rainy night in Malibu, land of improbable survival. At the end of the interview, he showed me the little messages he wrote for him on the inside of his sneakers, things like, “YOU’RE A WINNER” and “LET’S KICK SOME ASS TODAY.” Common sense with charm.

ALI MACGRAW: Mark, how long have you been doing gymnastics?

MARK CASO: I’ve been doing it since I was ten and I’ve been doing it all-out, intense since I was in eleventh grade—that’s when I set my goal that I wanted to make an Olympic team.

MACGRAW: And you picked UCLA because it has an extraordinary coach?

CASO: Yes. When I first decided to go there, UCLA as a team had not been heard of in the country because they didn’t have anyone. They had never even made it to the NCAA championships. But a new coach was signed and two gymnasts came on—Peter Vidmar and Mitch Gaylord, who I knew since I was competing. I decided that they were guys with the same sort of goals I had and it would really be a good idea if we all went and put UCLA on the map—which we all did. So that was my main motivation for going to UCLA. It was the right time with the other gymnasts and there was really good coaching and it was the right thing to do.

MACGRAW: You said something before about the intensity of these eight months. Once the Games are over, do you expect to—

CASO: I plan on retiring after the 1984 Games. I’ve had a lot of things happen to me in my life and I decided that I will definitely have had enough gymnastics by 1984. So I’m just going to go all out and work every day until those Games are over and give it my best shot. I don’t want to… Every day is going to be a total commitment on my part because of the fact that when I retire I want to say that I have no regrets and I think I’ve done the best I could possibly have done. That’s why I’m being so intense right now.

MACGRAW: Would you ever coach?

CASO: Hell, no.

MACGRAW: I know that you’ve traveled and excelled all over the world, but tell me about the accident a few years ago.

CASO: In 1980, I qualified for the Olympic trials and while I was in the training session, I broke my neck at the UCLA gym. I had paralysis from my shoulders down and they got me into the hospital where I went through a series of tractions and spinal fusion surgery and all kinds of stuff. That put me out for a year.

MACGRAW: Did you think you’d ever be able to move again?

CASO: When it happened to me I was just laying there and I said to myself, “Why am I doing gymnastics? What’s the purpose? Why did I do anything so stupid—this whole sport is insignificant.” Then I had visions of being in a wheelchair all my life and I thought, “Damn, who’s ever going to marry someone in a wheelchair?” But in the end everything worked out alright and I’m okay.

MACGRAW: How did you work back to place you’re at now?

CASO: We took it real slow. When you go through something like that you have a lot of mental fears and it was a real touch-and-go thing. No one really knew how much they could really push me without being dangerous about it. The interactions between me and my coach was just communicating and finding out just what we could do…

MACGRAW: Was there a point where you realized you were free?

CASO: It’s funny. I felt freer and freer the further I got away from the whole episode. It’s like time heals all. I feel like I was never injured now.

MACGRAW: Your attitude about living and your commitment and not looking back—that’s winner stuff. I think that’s self-perpetuating energy when you think you can do something and you do. I’m just knocked out because I think that kind of drama could turn a lot of people’s lives in a totally different direction and you’ve obviously put it in your life bank as an experience. You broke your neck in 1980—

CASO: In January.

MACGRAW: And you started competing internationally?

CASO: A year later I made the U.S. National Team. I had never been on the Team prior to my injury and it turned out I used all the motivation and drive I had just to come back and be a normal person. I went further than that and became a better gymnast and after that my career took off.

MACGRAW: As a spectator, what you do seems to me a great deal like dance. It’s a perfect marriage of athletic ability and dance. I think when we watch any great athlete, what we see becomes interchangeable with dance.

CASO: It’s amazing how a dancer can look at gymnastics and make the perfect corrections. She’ll say things like coaches will say. She’ll say, “That didn’t look big enough.” She’ll use terminology that I can relate to as a gymnast.

MACGRAW: Everyone can relate to gymnastics. Do you have any sense of the kind of audience you’ve been exposed to and are certainly going to be exposed to in the Olympics—hundreds and hundreds of millions of people.

CASO: There was only one time that I was turned off by any kind of audience and that was during the Pan American Games.

MACGRAW: But you won, didn’t you?

CASO: I won three medals there. The fact is they were so anti-American that I had to find a different sort of motivation to do well there. They wanted to see all us Americans get killed. They were throwing things at us and screaming things at us while we were competing. It was a terrible experience. But I learned a good lesson there—I learned how to de-focus the crowd and go out and show what I can do in spite of what people are trying to do to affect your performance.

Carl Lewis, Track & Field

by Carolyn Farb

At 21, Carl Lewis may be the greatest track athlete of all time. A master of the long jump, with a personal best of 28′ 9″, Carl is the only man to have approached Bob Beamon’s still unbroken 1968 record of 29′ 2½”. Actually, Carl has cleared over 30′, but the jump was disqualified over a much-disputed marginal foot fault.

A phenomenal sprinter, Carl Lewis speeds through 100 meters in 9.96 seconds and covered that distance faster than anyone in history in the final leg of 4×100 meter relay at last year’s Helsinki games. Videotapes show his time to have been an amazing 8.9 seconds.

Carl is also heading towards a record in the 200-meter dash. At the 1983 T.A.C. (The Athletics Congress) meet, the exuberant runner, anticipating his victory, threw his arms up in the air, pulling back slightly as he broke the tape at the finish line. His elation coast him a world record by 1/100th of a second.

A patriotic, born-again Christian, Carl is only one of a family of outstanding athletes, including his younger sister, Carol, the United States women’s long jump champion.

Carolyn Farb spoke with Lewis in the library of her Texas home, later continuing the conversation at the University of Houston track where “the best American athlete since Jesse Owens” trains.

CAROLYN FARB: You and Mary Decker are strangely compared to one another.

CARL LEWIS: I think that Mary and I are linked together because we’re somewhat unique. I am somehow in a position of following a hero in Jesse Owens and Mary Decker is something of a darling.

FARB: How do you train?

LEWIS: I train rather differently, I guess, because I spend two hours a day on it, eleven months a year. I train as a sprinter and a long jumper, so it is a very intricate but very interesting type of workout schedule. I usually work two days a week on my sprinting and two days a week on my jumping. I reserve Fridays for whichever one I didn’t do as well in that week.

FARB: How do you know when you do well? Is it when your coach says so or is it something you feel?

LEWIS: It’s something I feel, basically, because I think when a person does well at anything he tries, he feels a personal satisfaction. They realize they really worked hard for it and it’s something they can recognize.

FARB: Is there a special way you mentally prepare yourself for a race?

LEWIS: I might be a little more low-key than most. I’ve never been the kind of person who has had to sit down and ponder the situation to psych myself up. I just feel a confidence in competition that comes from training well and having a good idea of what I’m doing. I have a sense of confidence because I’ve worked hard and I have a peace of mind and ease about competition so I don’t have any secrets or do anything special.

FARB: Do you look at your body as if it were a finely tuned machine? Do you have a little mental checkout that you do?

LEWIS: I do in competition. Mainly because regardless of how finely tuned you are and how hard you work and how well you train, you’re still going to make mistakes. You have to mentally check yourself and make sure you go over a list of things you must be ready to do—make sure you keep an idea of all the areas you want to stay involved in. That way you can keep the body as finely tuned as possible.

FARB: Who encouraged you?

LEWIS: I guess the encouragement came from my parents. They started a sports program in the town where I’m from in New Jersey, and they gave me the opportunity to start in track and field. My sister Carol and I got into the program as the years went by. It wasn’t a situation where they pushed. I think they were a little reluctant to get us involved mainly because they were afraid of pushing.

FARB: They didn’t want you to be disappointed, perhaps.

LEWIS: Exactly. They maybe held us back a little at the beginning, but Carol and I kept pushing and pushing and they just opened up things and let us get involved.

FARB: They’re both coaches, aren’t they?

LEWIS: Yes, they’re coaches at rival high schools now. I remember one particular year when a meet was going on and it was very, very close. It came down to two events with my father’s team leading by one point, and it just started to pour out of nowhere. They had to postpone the rest of the meet until the following Thursday. We were sitting in the house with my parents as rival coaches. There were no dinners cooked.

FARB: How do you spend your free time, or don’t you have any?

LEWIS: I don’t have a lot and I’m involved in Radio/Television at the University of Houston, so school takes up a lot of my time as well as some of the sports activities I mentioned earlier. Then just doing little tidbits here and there—I advertise for Xerox of Japan and BMW of America so that keeps me very busy and little things I do—speaking engagements and interviews like this one today—and I’m involved with muscular dystrophy… millions of things.

FARB: Do you speak before many different groups?

LEWIS: Yes. I’ve spoken before all types of groups and banquets and I’m also involved in Christian organizations.

FARB: Do you have a lot of fan worship?

LEWIS: I do and I think one thing is that I come from a typical situation. I was in sports at a very young age. Most people say that if you start at six or seven you burn out and your parents push you too hard. I was in that type of program and I went from nowhere to where I am right now. Until high school I was a small athlete, scrawny and a late bloomer. By being that way, I was able to see both sides of the coin. My sister was somewhat different. She was always out in the front, always won, always the best. I was totally the opposite. I think I was rather typical in that respect, and that’s how people can relate to me—I always let my personality show.

FARB: Your coaches speak very highly and say you’re very easy to know and you’d be good at anything you did. Coach Doolittle described you as an “artist”—how do you react to that comment?

LEWIS: Of course, I take it as a compliment because anyone who is respected must have a tremendous amount of confidence to do anything active as well as a lot of discipline and a lot of concentration. So I respect them very much—I’ve been here four years training under them and always gotten along very well with them. To hear the comments that they’ve made is very encouraging.

FARB: What is the difference between a sprinter and a long distance runner?

LEWIS: One difference, of course, is stamina—sprinters are just not born with the stamina. There are different types of muscle fibers in the body called “fast twitch” and “slow twitch.” Fast twitch are sprint type of fibers where you get strength, quickness: football players, track and basketball athletes, have them. Slow twitch are distance runners, swimmers in most cases, and other areas that require long distance and endurance type of training. That’s one difference. It also takes two different types of minds. Distance runners work hard in one aspect—they work harder hours because they go out and do distance runs and a track workout which is very tough. Sprinters come out and have a short workout, which is very tough as well, because it’s very fast but it’s difficult. I think the main difference is that they’re born with different types of muscle fibers.

FARB: Is there something spiritual that makes you project?

LEWIS: Yes, I think so. I am a very strong Christian, number one, and I think that one thing has helped me. I’ve only been a born again Christian three years, and it has given me peace of mind. Now I know that everything I do to the best of my ability is all I can do. The Lord has given me a talent in the area of track and field as well as other areas, and there’s always improvement regardless of how old or young you are. As long as you let your personality show and try your best to improve and realize that the Lord is our main Being, giving us the strength to do it, I feel a lot more confident in my competition.

FARB: Your sister, Carol, is an outstanding athlete. Is she a long jumper? Has she even placed in 100-meter hurdling?

LEWIS: Carol mainly dabbles with the hurdles just to have something else to do. She hasn’t competed in any major hurdle competitions, but in the long jump, of course, she’s been the national champion and was third in the World Championships, so she’s really excelled. When there’s nothing else to do, she may hurdle. When she competes for the University, she runs a conference meet, in the hurdles, but she doesn’t like them that much. She just likes something to do and it is an event closely related to the long jump.

FARB: Did she make the Olympic team?

LEWIS: She made the Olympic team in 1980—she was the youngest member at 16.

FARB: I understand you have other interests—that you collect crystal and silver.

LEWIS: Yes. I’ve been to Europe eight times and the idea of crystal always intrigued me. Three years ago I went with my agent; he has always collected crystal and red wines, so one year we went out looking at crystal. It was interesting to see the ideas in crystal glass, so from that point on I started getting different pieces and reading up on it and learning about the different ideas. I graduated into silver and it’s been an interesting hobby because I get to go to Europe so frequently. I’ve had a good time.

FARB: When you come home it’s like your refuge from the world.

LEWIS: Exactly.

FARB: How do you handle pressure at your level of competition?

LEWIS: I guess it all goes back to confidence. I go into a competition and since I have a clear idea of competing at a certain level and in a certain area, then I’m going to be at the top of the ball game with the best people. Since I’ve been number one I go as hard as anyone else.

FARB: To make sure you keep your goals or meet even higher ones?

LEWIS: Yes. Two years ago I was number one in the world, and if I had run the exact same times, I would probably have been third or fourth in the 100 meters and second in the long jump. People are coming as fast as I’m going, so I have to be a little bit faster. It’s like a cycle. The person who gets to the top must keep improving and when they get to a point or an age where they can’t improve anymore, then they step down and someone else comes up from behind. It always works that way.

FARB: It works both ways and you have to protect yourself in a certain way. The NCAA rule does not permit funding but now isn’t it legal to receive funding in a trust through The Athletics Congress?

LEWIS: That’s correct. The NCAA rule prohibits strongly and strictly an athlete making any type of money, so an athlete like myself, let’s say I was on a scholarship, would be getting X number of dollars in scholarship money. Let’s say I stay in the dorms. My room and board and tuition are paid for and I get $20 a month to live on. That’s what a typical full-scholarship athlete gets. If I were to decide I wanted to go out and get a part-time job—say my season is during the spring and I wanted a part-time job and a friend would give me a job to work September, October, November and December for the offseason—well that’s not allowed under the NCAA rules because they say you’re earning money under the University so you’re not allowed to make any money yourself. The Athletics Congress is the governing body of track and field, excluding the NCAA, and they allow advertising and basically anything a professional can do—even prize money at certain track meets now. But it has to go into a trust fund.

FARB: So T.A.C. is more directly related to the running company?

LEWIS: Yes, the running community in amateur athletics. The NCAA does not allow you to make any money outside of the tuition, room and board and $20 a month the university pays you. That’s why there’s so many problems with collegiate athletes. Like in football they have a system where the NFL cannot intrude into the collegiate system. But now the players are saying, “How can we live for four years on a simple scholarship?” Track and field athletes did not have that problem before because track and field were not making any money. Now that they’re getting attention and starting to make money there’s a problem. So athletes are starting to leave universities and run amateur. Once they’re where they could be world class, they may leave track and field and join basketball. They’re starting to become younger and younger, and now football is going to start so the NCAA is going to have to change their rules or they’ll lose too many athletes.

FARB: I was going to ask you about the recent steroid controversy.

LEWIS: I think the philosophy is that, when I was young, I was exposed to steroids, that is I’d heard about them. When I was out of high school I heard that they were testing for steroids and I said, “What is this?” The coach told me that, in my event, it didn’t make much of a difference. They might make you stronger or a little bit faster, but the person who is doing things correctly is going to beat a person on drugs who is doing it incorrectly. If you make mistakes, you might be a little bit stronger, but you’re going to make mistakes anyway. I don’t necessarily believe in them because I don’t think they help that much. But, as I stated before, if someone decides to take steroids or any drug, that is their responsibility. I don’t think it’s right or good but…

FARB: You’re not sitting in judgment.

LEWIS: Exactly. Anyone can do what they want to do. Who am I to judge?

Evelyn Ashford, Track & Field

by Margy Rochlin & Lance Loud

Born in Shreveport, Louisiana, Evelyn Ashford discovered her talent for the sprint in junior high school when she began competing against boys in lunchtime races and found she could beat most of them. In 1975, she came to Los Angeles to compete for Wilt’s Wonder Women in an AAU Championship. The following year she was recruited by Chuck DeBus and subsequently made the U.S. Olympic Team. Although she did not make it past the trials, the 17-year-old showed promise. She became recognized as world-class when she won the national championship in 1977, in the 100-meter and 200-meter events and set an American record in the 200 meters.

Once she stepped into the limelight, her talent was enhanced by her flair for showmanship on the track. In 1982, Ashford created a stir by wearing a shiny, spandex-like neck-to-ankle body stocking, adapted from a speed skater’s uniform. From then on speculation as to what Evelyn will wear has become a traditional topic at meets where she is running.

Ashford, along with archrival Marlies Gohr of the German Democratic Republic, is the current favorite for the gold medal in the 100 meters. Ashford beat Gohr in ’79 and ’81, but Gohr trounced Evelyn twice last year. At the recent Sports Festival in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Ashford broke Gohr’s world record with an altitude-aided time of 10.79 seconds.

Because Evelyn Ashford rarely gives interviews, she is considered something of an enigma in the sports world. She has a reputation for being terse, unsociable, and fiercely competitive. Few of her competitors know her, but most have felt her chill. Ashford claims that her competitors’ protestations are overblown and unfair, but that they do have an effect. Small talk is distracting; it breaks concentration. Friendly gossip is for those who don’t mind being second best.

We met Evelyn Ashford near the UCLA track. After we were halted by a hulking bouncer-type demanding to see our credentials, Ashford peeked from behind a large fence from where she had been viewing the altercation. Stepping in front of her overzealous protector, she guided us to a nearby bench where we began the interview. Ashford fielded questions with a warm, off-track humor, punctuating most of her answers with long laughter.

EVELYN ASHFORD: What’s that you were reading?

MARHY ROCHLIN: The newspaper. What’s your sign?

ASHFORD: Aries.

ROCHLIN: Do you want to hear your horoscope for today? Joyce Jillson wrote it and she’s always right: “Touch base with former colleagues, they have good news. New love appears. Good financial promise is on the horizon.”

ASHFORD: All right!

LANCE LOUD: And we’re your new loves!

ROCHLIN: Lance, she’s married.

ASHFORD: I’ve been married for five years. I think people don’t know because I use Ashford instead of my married name, which is Washington. My husband coaches basketball.

ROCHLIN: Do you and your husband work out together?

ASHFORD: We used to, but not so much anymore. I train in the morning and he comes home by the time I’m finished.

LOUD: Where are you from?

ASHFORD: All over. My father’s in the Air Force.

LOUD: I think that’s great. I’ve always envied people in that position.

ASHFORD: Really? Don’t. You finally get into a routine and then you have to pick up and go.

LOUD: Yeah, but you’re the officer’s kid!

ASHFORD: Officer? I wish he was an officer.

LOUD: One thing I keep thinking about in conjunction with Los Angeles and the Olympics is the smog. I know that if I don’t run early in the morning I feel just like someone has taken their fist and smashed me right in the chest. How do you feel?

ASHFORD: Well, I’ve been living in L.A. for the last seven years and the smog is not going to bother me. I don’t care. I run in this every day. It might bother other athletes. It will bother people who aren’t used to it.

ROCHLIN: Where do you work out?

ASHFORD: I used to work out here at UCLA.

ROCHLIN: A lot of movie stars run on this track.

ASHFORD: They sure do. You name ‘em.

ROCHLIN: Do they recognize you?

ASHFORD: Sometimes.

LOUD: Doesn’t that get to be a drag?

ASHFORD: I’m out there for a job. It doesn’t faze me one way or the other.

LOUD: Can you relate to the whole show business angle in sports?

ASHFORD: When I began running I didn’t think about showmanship. But there is that whole aspect. You want people to know that you’re having a good time. It makes you more popular and carries over into other stuff.

ROCHLIN: Your attitude towards dressing up for a track meet sparked a revolution in the world of women’s track.

ASHFORD: I like to look feminine. There’s this whole thing about women athletes that they’re not. Wearing shorts and a T-shirt is not feminine to me. A one-piece leotard is easy to wear, fun… I go to dance shops all the time looking for new outfits. You know, I’m very competitive, too. I want to be known as feminine, but competitive. They can go together.

ROCHLIN: What did you think of Personal Best (1982)?

ASHFORD: I’ve only heard negative things about it so I’m boycotting it. It bothers me that my fellow athletes—people who I still compete with today—were in that movie.

ROCHLIN: You’re considered the champion of the “natural athletes”—no steroids.

ASHFORD: I am natural. I think most American athletes are natural. I think Jamaicans are natural. Some of the Canadians are natural. I’m not sure about the rest. It might be about 50-50.

ROCHLIN: How can you tell when one of your competitors is taking steroids?

ASHFORD: You don’t know?

ROCHLIN: What about gross amounts of facial hair? Wouldn’t a beard on a woman indicate something?

LOUD: Women take steroids? I thought only men take steroids.

ASHFORD: [laughs] You’ve got a lot to learn. What steroids do is that they allow you to train harder. You can have a larger workload and you can be more aggressive. That’s what you have naturally, Lance, because you’re a man. Steroids make you stronger, but they are very bad for you. I mean, women have to have babies.

LOUD: Do you want to have babies?

ASHFORD: Sure I do… Eventually.

LOUD: You know, Evelyn, you’re kind of a mystery woman.

ASHFORD: Good. I think I should be known for my running. My merit is on the track. I’m basically a private person. I don’t think I’m that interesting. The most interesting thing about me is that I can run. Period.

ROCHLIN: Do you have any national contracts?

ASHFORD: No, but I’d love to.

ROCHLIN: Mary Decker represents Kodak and you’re certainly at the top of your event. Do you think you don’t have any national contracts because you’re black?

ASHFORD: Yes. Mary Decker will get more than I ever will.

ROCHLIN: Do you have any commercials that you’d really like to do?

ASHFORD: Oh, yes! I want to do that Canon commercial, the one where they snap the camera? I could be flashing by really fast frame by frame.

ROCHLIN: Do you have a rivalry with Marlies Gohr?

ASHFORD: I don’t want to call it a rivalry. I think I’m the best of the natural athletes and the she’s the best of the robots. I say natural will triumph over robots.

ROCHLIN: Have you ever talked to Marlies?

ASHFORD: Nope. We’re not too friendly, you know.

ROCHLIN: You don’t even secretly check her out while she’s warming up or something?

ASHFORD: To tell you the truth, I think I frighten her.

ROCHLIN: Do you do anything to increase her fear?

ASHFORD: Yeah. I act mean. And black. [laughs] Just kidding.

ROCHLIN: Maybe whenever you go by her you could sort of growl. Go “Grrrrrr.” That would scare her.

ASHFORD: There is a language, you know. You don’t even have to say anything. Your competitors can feel it. You just vibe ’em.

ROCHLIN: You have a reputation for being the very best, for being very secretive and, lastly, not very friendly. But you’re very charming. Very funny… What gives?

ASHFORD: Wait a second, it’s my competitors that have told you that I’m not very friendly. I’m very standoffish with my competitors because in a spring so much can happen. But 90 percent of it is mental. It’s a sight job. If they feel they can’t get close to me then I have the edge. But we’ll talk and have fun—after the race is over.

LOUD: And you’ve won.

ASHFORD: Right. But it’s different with a relay. Like when we beat the East Germans during the summer. You all have the same goal, you all want to win. It’s electrifying.

ROCHLIN: Do you eat junk food?

ASHFORD: Are you kidding? Yeah! Ice cream. My favorite flavors are Pralines ‘n’ Cream, Rocky Road, and anything with chocolate in it. I eat what I want to eat because I’ve never had a weight problem. My sophomore year at UCLA I decided that I wanted to be a vegetarian so I stopped eating meat. It was terrible. Meat makes you very aggressive.

ROCHLIN: Whenever you’re competing in a meet the people in the stands love to sit around and speculate what wild outfit you’ll be wearing this time. And it always seems like you wait until the very last second until you pull your warm-ups off and…

ASHFORD: TA-DAHHHH!

ROCHLIN: Does that kind of attention give you a competitive edge over the other sprinters?

ASHFORD: No, I do it for the fans. I want everyone to know that you can run and sweat and still look nice.

LOUD: Do you train seven days a week?

ASHFORD: Yes, and it might not sound like a lot to you, but in the mornings I train for two hours and then on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays I train for two more hours in the evenings.

LOUD: And by training you mean running?

ASHFORD: Running. These joggers are not running. If I had to jog I would quit running. You know, after I broke the world record in Colorado Springs, I came here to UCLA to train and every jogger on the track came up to me and told what was wrong with my form. I couldn’t believe it! Sometimes people come up to me and say, “Are you Evelyn Ashford” and I just tell them no.

Jack Kelly, Sculling: 1948, ’52, ’56, ’60

by William Sibley

One could easily mistake Jack Kelly for the square-jawed model in an Arrow Shirt ad. This handsome, 56-year-old father of six (fiver daughters and a son) and brother of the late Grace Kelly is serving not only on the Executive Committee and Board of Directors of the Los Angeles Olympics, but also as First Vice President of the United States Olympics Committee. Having competed in four consecutive Olympics, (1948, ’52, ’56, ’60) in the Single and Double sculling events, he was, at one time or another, the Singles and Doubles Champion of the Pan American Games; the Swiss, Belgian, Canadian, Mexican, United States, and Philadelphia Singles Champion in 1949, and winner of the 1947 AAU Sullivan Award as the Outstanding Amateur Athlete in the United States. It’s a safe bet to say Jack Kelly knows when to keep his oars in the water when it comes to international competition.

Interviewed at his offices in downtown Philadelphia, (he is the Chairman of the Board of John B. Kelly, Inc.-Masonry Contractors) he discussed the roles of business and sports, Olympics and politics, and amateur athletics in general—as well as Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and the principality of Monaco. On the wall beside his desk is an enlarged photograph of Jack and his three sisters, taken at the shore when he was just another towheaded five or six-year-old. Next to it, in virtually the same identical grouping, is a photograph of Jack and his sisters taken only a few years ago. Jack, Peggy, Liz and Grace—the Philadelphia Kellys. All vigorous, smiling, healthy and attractive; a picture of the idealized American family incarnate. Talking with Jack Kelly reminds one of the nobility of the world “family,” and of the undeniable pride and distinction that comes from a lineage of such achievement.

WILLIAM SIBLEY: From the business point of view, how do you feel about the way the Games are being handled in Los Angeles?

JACK KELLY: I think they’re doing a terrific job. It’s the first privately-operated Olympics ever. They’ve always been backed by a government before; this is the first time private enterprise has tackled the Games. They expect to make a profit for the first time since 1932.

SIBLEY: Will there be a lot of commercialism—Ronald McDonald painted on swimming pool bottoms, what have you?

KELLY: There’s going to be some, of course, but I think no where near what it was like at Lake Placid. There are only 30 or so corporate sponsors for L.A., versus the over 200 that were in Lake Placid. There won’t be any official “nail clipper” or that kind of gizmo. It’s a rather more exclusive participation.

SIBLEY: Are we setting new criteria for funding Olympics?

KELLY: Not exactly. It probably couldn’t happen anyplace but in America—the Korean government will be very involved with the 1988 games. You see, television income has become so substantial that it helps to make an event like this conceivably profitable. ABC has bid $225 million for the U.S. rights and then there’s another $100 million or so for the international rights as well. It’s almost three times greater than any previous Olympics. Of course, if certain countries decide not to show, that figure could be diminished.

SIBLEY: Any clue as to what the Russians are going to do?

KELLY: I think they want to come very badly and they’re be here unless there’s absolute, complete world upheaval. They put a very high priority on sports, they’ve been working very hard and they expect to do very well. I think it was a huge disappointment to them we didn’t show in ’80, and naturally whenever the two superpowers fail to compete in amateur competition the event loses some of its pull.

SIBLEY: We seem to be so closely aligned with them in many of the same fields, would there be any serious competition without them?

KELLY: Actually, they’re more consistent in their ability than we are. They stress every Olympic sport, and we in this country are really only proficient in a few of the more popular ones. The majority of our top athletes do not participate in Olympic sports—baseball, football, golf, and tennis are not Olympic sports. In Russia, a style of manufactured popularity is promoted in sports that aren’t traditionally Russian. Can you name one famous weightlifter in this country? Field hockey player? Fencer? Wrestler?

SIBLEY: Are you from the school that says we ought to move the Olympics permanently back to Greece?

KELLY: No. First of all, that was voted down by the International Olympic Congress in Baden-Baden two years ago. Secondly, the Greeks can’t afford to build the facilities—who would pay for them? Thirdly, what happens if there is a coup or an overthrow of the government unfavorable to an Olympics in Greece? To spend the kind of money necessary and situate the Games there indefinitely would seem rather foolhardy considering the vagaries of world politics.

SIBLEY: What is the selection of an Olympic site based on?

KELLY: The facilities one offers, the housing available, public access…

SIBLEY: And what exactly did Sarajevo, Yugoslavia have to offer?

KELLY: Well, you have to believe them when a city or government makes a commitment. Sarajevo has built some beautiful facilities for the Winter Games. The only thing lacking is probably enough good, first-class hotels.

SIBLEY: Is there any possible way of dealing with all the political questions that arise during an Olympics?

KELLY: Well, we always used to say that the Russians and the Communists mixed politics and sports and we didn’t, but that certainly is not the case anymore—if it ever was. The Carter Administration wouldn’t even issue us visas, and that’s a rather effective governmental decision, I should think. It’s virtually impossible to ignore the state of the world, Olympics or not.

SIBLEY: You competed in the Olympics in rowing. For all the novices out there, primarily myself, would you explain the difference between crewing, sculling, and just plain rowing?

KELLY: Competitively speaking, crewing is, of course, done with a team, sculling is when you have two oars, and rowing is when you use just one.

SIBLEY: Give me a composite description of the quintessential rower—is it Jack Kelly?

KELLY: I’m maybe a special case since my father was a very active rower, but I’d say the average rower is a young man or woman—a third of all our rowers today are women—someone who happened to go to a school where rowing was an activity, either through a club or a full sports basis, and after their education they sought out an organization to continue rowing through.

SIBLEY: How did your father, Jack Kelly Sr., get involved in rowing?

KELLY: He grew up here in Philadelphia, near the Schuylkill River, and he saw a lot of the events going on and he just decided he wanted to be a part of it all. It’s a very exciting sport.

SIBLEY: Would one also call this an Eastern, elitist sport?

KELLY: No.

SIBLEY: Do they row in Texas and Arizona?

KELLY: There’s only one school I know of in Texas, none I know of in Arizona. In California, there’s probably 20 or 30 colleges, maybe a dozen high schools that offer rowing. Seattle’s the biggest rowing city in the West. The University of Wisconsin has a big rowing team.

SIBLEY: But more or less, it’s something you pick up in school and are limited to joining a club afterwards.

KELLY: Some people who live near a body of water might do it on their own. There’s a big trend towards these wider, lighter plastic boats called “Lasers” or “Martin Trainers.” They’re more stable, but they’ve still got the same sliding seats.

SIBLEY: The history of the sport is English.

KELLY: The rules and type of rowing we do in America were established back in the early 1800s in Great Britain. Rowing, however, is probably one of the oldest activities in the world. The Egyptians used to race each other on the Nile; the Greeks, Phoenicians, Chinese, Norsemen—all competed in rowing. The earliest any two universities or colleges ever competed against each other in any sport was the Oxford-Cambridge race, and the earliest intercollegiate athletic event in America was the Harvard-Yale race in 1852.

SIBLEY: What does a “cockswain” mean?

KELLY: A cockswain steers the boat—obviously you can’t see where you’re going while you’re rowing. If he’s a good one, he’s almost like a coach, making sure everyone’s in time, psyching them up.

SIBLEY: Do any of your children crew?

KELLY: Three of them. My number two daughter rowed in high school, my son rowed at Harvard and became captain his senior year, and my youngest daughter, who just turned 17, rows at her school.

SIBLEY: Any potential Olympians there?

KELLY: Doubtful, but stranger things have happened.

SIBLEY: How about your sisters?

KELLY: Rowing wasn’t as fashionable for women back then. They were big on field hockey and basketball. I think my youngest sister Liz was the best of the bunch. Peggy had tremendous potential when she was younger, and Grace was—well, Grace was more interested in acting.

SIBLEY: Does Prince Albert crew with a team?

KELLY: He’s rowed some in Monte Carlo. When he attended Amherst College he played soccer mostly, and he’s a very good swimmer. Albert’s a decent all-around athlete and a real gentleman.

SIBLEY: Have you been back to Monaco since your sister’s death?

KELLY: No, I haven’t. I do so much traveling that’s sports-related it’s hard for me to justify taking off more time to go over there.

SIBLEY: Recently, in New York, your sister Grace re-appeared in the film Rear Window (1954) and it out-grossed practically every movie in town. Can you explain this phenomenon over a 30-year-old film?

KELLY: Well, whoever it was, Hitchcock or somebody, kept it our of distribution all these years. It hasn’t even been seen on television, and I think there’s a whole generation now discovering Jimmy Stewart and Hitchcock and Grace and that style of filmmaking for the first time, and they’re very, very interested.

SIBLEY: Did you ever want to be an actor?

KELLY: [smiling] I have a lousy memory for remembering lines—maybe if they bring the silent’s back.

THESE INTERVIEWS ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.