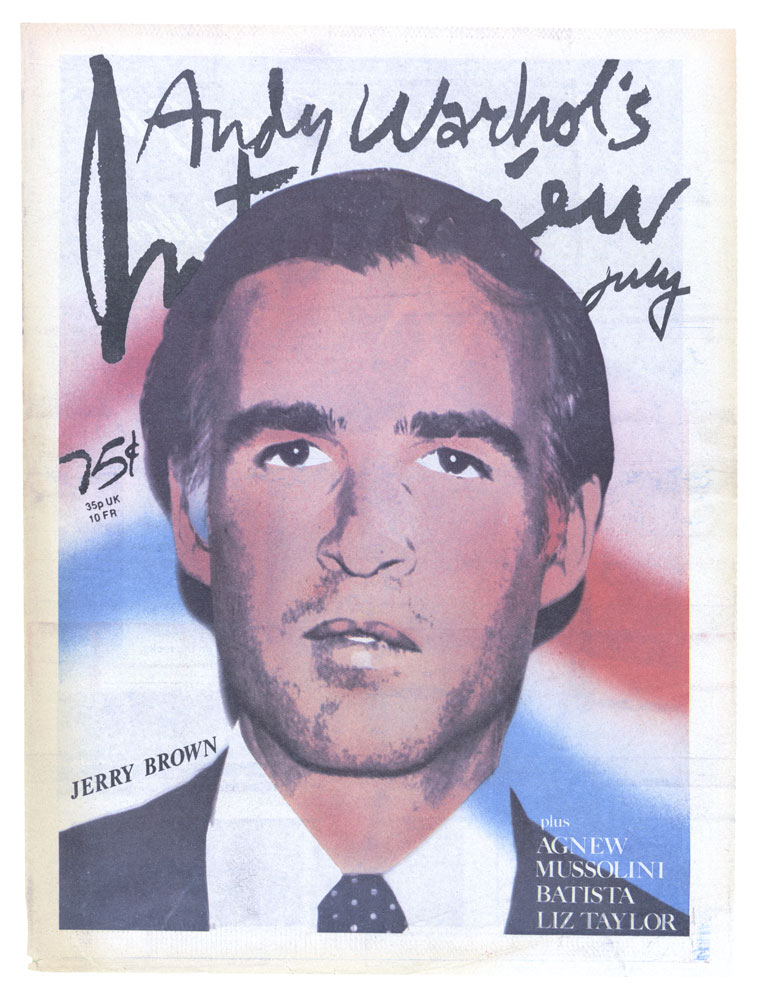

New Again: Jerry Brown

It’s been quite a week for legislation in the United States—nationwide, statewide, and citywide. The biggest landmark, of course, was the legalization of same-sex marriage by the Supreme Court of the United States last Friday. The New York City Board soon thereafter also made history, approving a rent freeze for stabilized apartments for the first time in its 46-year history. And yesterday, California Governor Jerry Brown signed one of the strictest school vaccination laws in the country into effect, eliminating all previous exemptions for students with specific religious or personal beliefs. Brown has been the governor of California since 2011, ran for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States three times, and also served as California’s governor from 1975 to 1983. During his first term in the State office, Andy Warhol thought it necessary to not only attend a fundraiser for the politician, but to also give him the cover of Interview‘s July 1976 issue. So in light of recent events, we’re revisiting the event and conversation nearly 40 years after it took place.

Jerry Brown

By Andy Warhol

On Tuesday morning, June 1, 1976, record producer Earl McGrath called Andy Warhol and invited him to a fundraiser dinner party for Governor Jerry Brown of California to be held that evening at the Central Park West apartment of “Al Lowenstein’s brother.” Allard Lowenstein is the former Congressman from Long Island who helped launch Eugene McCarthy’s campaign in 1968 and now is trying to do the same for Jerry Brown.

Andy Warhol attended the fundraiser and tape-recorded Al Lowenstein’s introduction, Jerry Brown’s speech, and the question-and-answer session that followed.

ALLARD LOWENSTEIN: I want to take this moment to welcome you and tell you what you’re here for in case it’s a mystery. Every eight years I come to you to introduce some leading Jesuit theologian who has suddenly decided to run… [laughter] But it seems to me on this occasion, there are enough people who have felt the need for a candidacy that would represent an effort to make politics more connected to our history and to the things that we’ve been working for, that most of you would like the opportunity to meet Jerry Brown. I’m going to say a little bit about him from my vantage point and then let him speak for as long as he wishes. As you may know, his inaugural address was seven minutes, so if he speaks for four minutes you won’t feel you’re being slighted.

My sense about Jerry Brown is one that goes way back because we were involved in Mississippi at the same time, many years before that was something that anyone thought would help you on your way to the White House. The next time that our paths crossed was in California in 1967 in the period when we were trying to find people that would stand up against the War. His father was then Governor, which did not make his role any easier, and he was the first person in California with a recognizable name who joined in the effort to put together a ticket that would run in the primary. So when I think about his history I know what his commitment has been on issue of race relations and social justice and peace and I have none of the problems of identifying with that history that I think some of you have had. I want you to know that because we come to the campaign not to refight old ones but simply to understand the sense of the people that are here.

His campaign this year has taken on a typical unorthodox, Jerry Brown turn. It started out when he discovered he has seven percent in Maryland. After Carter swept Pennsylvania and the polls in some papers showed him at seven percent he said, “Now’s the time to enter Maryland.” Which he did. It was required as an impossible race. He thereupon won it, carrying all segments of the state in a way that nobody had managed to do in a primary against Carter before. Subsequent to that he said, “Let’s find another place where the odds are with me.” And he found Oregon where he wasn’t even on the ballot. He therefore decided that was the logical place to run. He entered the Oregon primary not on the ballot and ended up defeating Carter on the write-ins, getting the heaviest write-in for President that anyone has achieved in the United States. Having done that in Oregon, he cast about and discovered that in Rhode Island there was a way he could run where it was illegal to write-in so he determined to do that and tonight we’ll hear the results from Rhode Island which, if they are as I hope they will be, will make it clear that he is a candidate that can run not only where he’s on the ballot or off the ballot but where it’s illegal to vote for him on the ballot. In pursuit of that trend towards easier and easier primaries, he’s now in New York where, logically enough, the voting’s already been finished. The theory is that he will now carry New York ex post facto.

There is about his candidacy something that many of you who have been involved in politics for a long time will especially welcome. There is a sense among people who have long time given up, who went through the bruises of the McCarthy campaign and then the disappointments after that, who’ve felt increasingly turned away from political activity—there is a feeling that again that somehow it’s worth being involved. That’s a feeling that each of us, I think, is at struggle about. Lots of times now one wonders. And I think that if this campaign has done nothing more than to make clear that it is not impossible to generate electricity and excitement and a sense of hopefulness, in the middle of talking very accurately about the difficulties we face, that it will go down as a very significant contribution. I want to finish by telling one little glimmer of the governorship of Jerry Brown. It’s easier for me to say this than for him, at least it should be, even if he’s not as modest as one day he will be. One night last spring I get a phone call at three in the morning and it was Governor Brown. My wife suffers through these things and denounces the people who call late. I told her that it was the Governor of California and he wanted us to come there. I don’t think he’s ever been clear that it’s three hours later on the East Coast although he knows that there is a time difference. In any event, we went out and spent the summer in Sacramento and discovered that this was the guy who as Governor of California had managed, among other things—I list only a few of them—to close the oil depletion allowance, to reduce the cost of government, to increase social justice for black people and poor people and Chicanos, to give protection of the State to farm workers and other people who have never had it before, to legalize homosexual activities among consenting adults, to decriminalize marijuana, to make it possible in any part of California for people who felt that government was irrelevant to change that sprit—I think that was the thing that was most extraordinary that I could find—and to do all that in a state that twice had elected Ronald Reagan while retaining an 89 percent approval of voters of California. So we have tonight somebody who is twice as frugal as Ronald Reagan, twice as Jesuit as Eugene McCarthy, twice as ruthless as Robert Kennedy, twice as garrulous as Hubert Humphrey…

The end of Lowenstein’s introduction is drowned out in applause. Then Jerry Brown gets up to speak.

JERRY BROWN: My speech won’t be as long so I’ll get to the point. I’m just finishing a month of campaigning throughout the East so my energy level is not as high as when I started. But, very simply, I got into the campaign because I didn’t think that those who were there in it then had generated the enthusiasm and interest that I thought was appropriate for a Democratic nominee. I looked at the candidates, I waited a long time and not much was happening so I decided to get in. I went to Maryland, then Pennsylvania happened—you left out Nevada, by the way, which everyone has left out. I don’t know why. Carter was ahead two-to-one before I went there and I did get 52 percent of the vote to Carters 22 and Church’s nine. I recognize the difficulty of the campaign but I have had success in each of the two places that I have entered. I think I had relative success in Oregon, Rhode Island we’ll find out tonight, and in California the NBC Poll indicates that I am ahead of Carter 52 to 22 to Church’s three, so that augurs well, too. It’s going to take a fortuitous series of events to make my candidacy possible or the nominations possible. It’s there, it’s possible and I’m going to try as hard as I can.

I really think the country’s facing a turn in the road. I think that we’re coming to the end of an era. I don’t see quite the easy economic growth that Carter seems to project. I think it’ll take more than love and reorganization to rebuild New York City and restore the momentum and full employment to the economy. I think it’s going to be very difficult in the years ahead. I think we’re facing a lot of difficult trade-offs. When I got to New York, when I went to Rhode Island, I sensed the divergency between the East and the West and especially the Southwest. Out in the West the perception is, “How do we get government off our back?” When I come East I get a sense: “How do we get government to help us out of a very difficult situation?” and how, I ask myself, can a President pull together those very different perceptions of what is the appropriate role for government? I think it can be done.

I’ve pulled together divergent groups in California—the loggers and the Sierra Club, the farmworkers and farmers, liberals and conservatives in a way that hasn’t been done before. I can’t guarantee that it’ll last forever but it’s gone on for a long period of time. And what I think the country needs is some vitality, a new sense of direction and a President that can put the issues in the larger framework. I don’t think what we’re looking for or need is a legislative draftsman, a committee consultant, I think we need a perception and vision of what’s possible. I’ve tried to do that in my own way in California and in the campaign. I’ve tried to indicate the general preferences that I would make. I’d like to try to slow down the arms race, I think you cannot create jobs at the expense of the environment, on the other hand I don’t think you can ignore the fact that eight to nine million Americans have no jobs. I think it’s nice to talk about requiring people to work as a condition of welfare but if the jobs aren’t there then that’s a very meaningless exercise, as we found out. Reagan had a work-welfare program which was a utter failure because there were no jobs. The same thing is true when we parole people to an 80 percent unemployment area of Oakland or of Los Angeles—what good does it do? So I think what a President can do is set forth the priorities and the potentialities of this country. And certainly the first priority is a full employment economy, the Humphrey-Hawkins bill, a measure of economic intervention by the federal government that I don’t think any of the other candidates have begun to talk about. And the fact is that the East is not going to make it without a very different relationship between the federal government and private industry. I think that’s just a fact. We have to equalize our energy costs, we have to assume the burden of medical care, we’re going to have to change the formulas of revenue sharing and we’re going to have to provide incentives to retain the economic vitality in this part of the country. It’s not going to be easy. I’ve not seen the recipe written down for how we make it. I know though that if we generate the same energy we have for the B-1 bomber and the defense budget that we ought to have for rebuilding cities—in some places they look like cities at the end of World War II—I think if the rest of the country could see that, if a President would go to Rhode Island and New York and let the rest of the country in on what ‘s happening, then I think this country would get behind the collective purposes that are needed to survive.

I don’t think the issue of this country is going to be decided in the Panama Canal, I don’t think it will be decided with the strategic weapons systems—if we missed one or two of the notches up in the arms race it wouldn’t make a heck of a lot of difference. I think it’ll depend on whether we can save the cities, whether we can provide full employment and whether we can restore a sense of candor and optimism to the federal government. That’s what I’d like to try to do. And I think the very issue that people have raised about my candidacy is its greatest virtue and that is that I would come to Washington as a new force out of the West, unencumbered with a lot of the alliances of the past, not untried in the political process—I’ve been around it all my life and I think I understand it—but with the ability to bring people together, to inspire some hope and try to get this country back on the up-beat. Every day you pick up the paper and it looks like we’re on the down-beat and I don’t think a country can long take that kind of momentum. I’d like the chance to go forward, I’m hoping for a good result in Rhode Island, I think the outcome in California will come out well, how the other primaries will go I can’t tell you but I’m going to try all the way to the end to give this party a choice. We need it and I think I can provide the leadership. That’s all. If you’ve got any questions I’d like to try to answer them.

LOWENSTEIN: You’ve got a question already? Can I say something here for just one second? People are leaving but before they do let me introduce them. Can Russell Hemingway and Gene McCarthy come back for a second? I was once riding in a car with Bill Buckley and I told him we had more differences of opinion in that car than any other time in the City of New York except when Jake Javits rode alone. And I think we have more differences of opinion in this room tonight than any time except when Gene McCarthy was here alone. [laughter] I just want to introduce Gene McCarthy and Russell Hemingway. [applause] Bayard Rustin, one of the central figures of American History, [applause] Harry Chapin, Betty Comden—I don’t know, everybody here is so famous. I don’t know where to start. Now we can go back to the questions. Where’s Andy Warhol?

Q: One of the main problems in foreign relationships is the Mideast situation. I would like to hear your stand on it specifically.

BROWN: Are you asking about Israel?

Q: Right.

BROWN: I have been a strong supporter of Israel ever since I can remember, from the bond drives of my father who has been participating in them in the early ’50s, to when I was Secretary of State being the first official and the only official to send in my Standard Oil credit card when the president of that company tried to get his shareholders to pressure the government for a change in Mideast policy. I terminated a contract with the California highway department that was going to be negotiated with Saudi government because it had discrimination against Jews. I’ve tried to express in all the ways I could all the time I’ve been in politics a very strong support of Israel. I see the problem very simply as America standing behind that nation. We have long historical ties until the Arabs are ready to sit down and negotiate and recognize the State of Israel, we’re never going to get anywhere. Until that time I support Israel to our capacity. I would not have vetoed the bill that Ford did that reneged on the 500 million dollars in economic aid and I don’t know that I would have given those C-130s to Egypt. I’ve got ten of my own out in California National Guard and I don’t know why Egypt wants them but I think it’s a step in the wrong direction. They’re big gas eaters at $800 an hour and I wrote an article when I was roundly criticized but…

Q: It may be symbolic.

BROWN: It symbolically keeps the door open. I think we have to put more pressure for recognition and back Israel. I think we’ve given them salami tactics. We give a little help here and then we pull it back and they’re oppressed. And they don’t think that they’re going to make it with some guarantee from on high. I think it’s got to come in the Middle East and our pressure ought to be to get the Arabs to sit down and talk. Yes, sir?

Q: Forgive me if I borrow some rhetoric from Carter: when you are President….

BROWN: You can say “when” or “if” or whatever. I am not able to foretell the future so I prefer “if.”

Q: I’ll say “when” Henry Kissinger will be back at Harvard and Wayne Hays and Carl Albert are obviously too busy [laughter] you are going to have a foreign policy. You are going to have a specific legislative program. What can we expect to find in it when you are President?

BROWN: Are you asking me the people or the programs? Do you want the entire foreign policy and domestic programs? In 30 seconds?

Q: No, but could you sketch the legislative programs you would support?

BROWN: I think the Humphrey-Hawkins bill—full employment bill. Change the revenue sharing formula. National health with a lot of disincentives for over-hospitalization, excessive operations and under emphasis of primary care. A revision of our foreign policy in a diplomatic way. I think the arms race is crazy—the nine billion that we are spending. I think we ought to start the process of slowing that down and to do that, of course, means a lot of jobs are affected so we’ve got to convert industry and find some other equivalent, whether it be space or rapid transit or whatever. We could do a lot of work right here just rebuilding the subway and whatever that road was I rode around on—the West Side Highway? [laughter] We need Strategic Weapons Systems to move people from one place in New York to another. In foreign policy, I frankly think that our relations with the Third World could be improved. I think we ought to try to aim for stabilizing the exchange of raw materials. I think we ought to have environmental concerns in our foreign policy. I think the oceans are going to be a dead sea in another 25 years if we don’t do something about it. I think we’re a very small planet, there are limitations to the resource base and we have to recognize that. At the same time I think we ought to make some dramatic investments in solar energy, in coal, in geothermal and in a very heavy emphasis on conservation. The automobile companies are trying to kill the clean air. The fact is that they have the technology to meet all the clean air standards. Right now Air Resources Board in California has done the test and has proved that Volvo has met all the clean air standards until 1980 and yet Detroit is trying to roll-back. I think the central issue in the country is the commitment to full employment, the emphasis on conservation which I think is very weak right now, and what that implies is coming to terms with what I don’t hear even people in this city facing up to and that is the private sector is not generating the jobs and therefore the government is going to have to intervene in the economy in a way tha we’ve never done before. I recognize that, I accept it, and I think we don’t have any alternative and I’m prepared to do that. How we do that, whether revising the tax incentives that have really depleted the city of its resources, revising things like investment tax credit to reward people who work in the cities—there are any number of things that you have to do.

The President is not the general manager of a department store. He’s not a committee consultant. It’s a question of where your values are. And I am persuaded that his country will not survive if the cities don’t make it, so that’s full employment, lessening the burden that cant be sustained in Detroit and New York and Oakland. It’s getting the people of the country to sense their own interconnectedness from California to New York to Florida to Maine. We’re all part of the same country. And I would try as President to educate and to lead people in that vision that we are all dependant on one another. If the cities sink the suburbs are going to follow, if the blacks don’t make it, the white’s wont either and that’s the defense we ought to talk about. It isn’t in Panama City ad it isn’t the old men arguing about how many missiles we have. Its whether those who want to have a piece of this country as we know it won’t make it for the rest of this decade. That is what I would try to emphasize.

Q: Let me tell you something. I think one of the criticisms of you as Governor has been your lack of specificity. Now I’ve never heard a man that’s been a candidate for President for one month or for a year able to respond to a very general question that asked for your whole spectrum of views with such great specificity, such great obvious study and intelligence with respect to these particular issues. I’d just like to say make sure that Al Lowenstein gets out to the public that you have thought through, as you obviously have, all of these things and these issues.

LOWENSTEIN: You know what else he’s done? In California, he’s given judge’s appointments to women, blacks and Chicanos.

Q: That’s not important.

Q: I think it is.

LOWENSTEIN: It is important.

Q: I think it’s important.

Q: It is not.

BROWN: I think that you’ve raised an important point. There is somewhat of a specificity fetish in this campaign. People go around yelling, “Issues, issues, issues!” and you ask them what their issues are and it is the invocation of the word “issue” ad nauseum. That’s Frank Church. I have not heard one specific out of that guy other than he doesn’t want to register hand guns and he’s for helping senior citizens in Rhode Island, which I think is fine. But I am the Governor of a large state, we’ve got a $13 billion budget, I’ve signed 1,200 bills, I’ve vetoed 145, I’ve an 1,100-page budget—all of that reflects in precise detail what I believe and what I don’t believe. And it’s there. People say, “How are you going to help the cities?” If we have a National Health Program, the $1 billion welfare load in New York City would be relieved to the tune of 450 million which is your Medicaid cost right here in this city. So National health alone cuts the burden right there. So if this is a Ph.D. exam I’ll be glad to put Carter and Church and Udall in the same room and take the exam. I’ll parrot back to you all the details and the specifics but I’ll tell you something. The facts and the experts are very limited and you can process them in your brain given a modicum of intelligence and enough study. For the last year and a half I’ve spent 12 hours a day, six days a week, dealing with the urban, the agricultural, the governmental, public and private sector in a state that isn’t all that different from most of the states in this country. In speeches you cant give every itemized detail of what you’re going to do but if you tell me an issue I’ll tell you how I’d approach it.

Q: You’re the only real candidate for President as far as I’m concerned.

Q: I would like a clarification on your stand on amnesty.

BROWN: Well, I’ve said that there’re different levels of people who are involved with this problem and I’d like to wipe this thing clean and bring everybody back. I’ve taken the position that some public service ought to be part of that general process. I suppose at some point the longer we get away from it the less important that is and I think it becomes kind of a moot issue. But that’s been my position.

Q: With 12,000 people out of the country you want them to work their way back? That’s what I want clarified because it sounds just like what Ford said.

BROWN: No, the Ford thing is to have this little inquiry board that checks everybody out and two years of public service that symbolically balances the fact that there wasn’t a law that was complied with. Some people paid the penalty, others didn’t and I think we can wipe the slate clean with some kind of public service. I don’t think the period has to be very long and quite frankly, if I am President, one of my most important objectives will be the creation of a public service corps that will not be a badge of servitude and dishonor but, hopefully, will have some kind of excitement as the Peace Corps, as the C.C.C. under Roosevelt, and will operate as a rite of passage, a point of transition, for many young people in this country. I hope millions. There’re a lot of people who aren’t going to college right away, don’t have a job and who could be a part of a public service corps and I’m willing to invest a tremendous amount of money in that because I think it’s very important, not only for employment purposes but for integration purposes. Men, women, people from rich and poor backgrounds, black, white—I think it’s an opportunity for a year or two to provide a very important service. Yes?

Q: In the state of California, how has private industry been victimized by your commitment to full employment?

BROWN: It hasn’t been victimized at all.

Q: The question I guess I’m asking you is: “How do you reconcile private industry giving up something and your commitment to full employment?”

BROWN: Why do you say private industry “giving up something”? I don’t understand you.

Q: I thought I heard you say earlier that private industry has to provide the jobs.

BROWN: Well, the fact is somebody has to provide the jobs. What’s the question again?

Q: How do you reconcile a commitment to full employment, i.e., the Humphrey-Hawkins bill, with fiscal restraint and…?

BROWN: I understand the question. Let me turn around the other way. We are now embarked on a course that leads to the vagary of the marketplace—the employment of millions of people who are not part of the economic mainstream. Now, what do you want to do with them? Do you want to try welfare? Do you want to try prisons, unemployment insurance, and the whole array of social services? Or do you want to provide not only the income maintenance but the status that comes with a job? I think that there’s no turning back—we either provide that full employment or you’re going to pull the country apart. And in providing it I’d like the private sector to carry the major burden. If it can’t do it we’re going to have some public sector back-up. I think at some point we’re going to have to share work. Private business is probably going to have to hire. It’s either that or the government. When you add in the cost of unemployment insurance, welfare, public defenders—all the other array of services that come from being out of work—I think the commitment to a full employment economy is a better bargain. I think this is the only real question: when you go down the route of full employment and expanded opportunity for those people who are left out you are talking about a new relationship between the government and the private sector. And I recognize that and I don’t think there’s any turning back. Industry has displaced people from arms, from the cities, through automation, through all sorts of things, and those people are still around. Now how do you want to bear that cost? The Reagan-Ford program is to say, “Leave the market alone and create a welfare system and unemployment insurance.” I think that’s running out. The unemployment budgets in 27 states are bankrupt. It’s not going to make it. it’s not going to make it economically and it doesn’t really make it morally because you not only have to have an income, you’ve got to have a job. I think it’s not the work of a year or two but over time, the role o the government has to operate to revise taxes, subsidies and expenditures, regulatory activities, investment, to create maximum employment.

Along with that, I think we’ve got to break down barriers. There’re a lot of monopolistic restrictions that are keeping people out of work. I think in the government, in the private sector, in the medical profession, there’re a lot of people who could do things that are screened out on the basis of irrelevant, unrelated job qualifications. I think a lot of primary care in the medical profession could be provided by nurses. It could be provided by midwives. Why not? Well because you have to have a Phi Beta Kappa key and 12 years of education. I don’t think that’s right. I think we’re going to have to destratify the medical profession. I think to sell real estate you shouldn’t have to have 80 units of adult education. I think to be a dry cleaner you shouldn’t have to have two years of junior college. I think the training of people is going to have to be borne more by the private sector nd I think the qualifications to get in are going to have to be reexamined a very systematic way along with investments in energy, investments in home building, investments in rebuilding the subways and roads and all the rest of the things that go on in society and that implies a rather important role for the public sector.

LOWENSTEIN: We only have time for one question.

BROWN: Yes, sir?

Q: Governor, you may not think this relevant but I hope you will. Al said that a lot of people are turned off to politics. The presence here of people shows they may have a new interest. A lot of people are not here, obviously, and you may be benefitting from that.

BROWN: That they’re not here?

Q: You’re benefitting from the fact that a lot of people have been turned off to politics and obviously that’s the reaction of the public. And I would like to ask you what are you prepared to do as a candidate at the present time to meet the challenge of a minority candidate—38 percent for Mr. Carter, when 62 percent of us are non-Carterites—what formula do you have to meet that challenge which does not necessary include your candidacy.

BROWN: Could you simplify that question? [laughter] Is this something to do with Udall or Humphrey or…?

Q: It’s something to do with this: none of you will probably get the nomination. Do you have a formula to meet that?

BROWN: I operate on the assumption that none of us has to be nominated. And it might not be Carter so it might as well be me.

Q: Does it have to be you? Or do you have any other formula of who you turn to?

BROWN: No, I take things one thing at a time. Why? Do you have a formula?

Q: No, I’m not a candidate. I’m thinking of the party and the country. I would like to know what your commitment is to the Democratic Party and the country which does not include you necessarily as the candidate.

BROWN: You’ve got to translate that into more specifics.

Q: So are you in a rush?

BROWN: Do you want to know who I’m going to back if I don’t make it? Is that what all those words mean?

Q: Do you have any formula to put a stop to the fact that, as its going now, none of the non-Carterites are going to make it? Do you have a formula for that?

BROWN: Well, I’d like to do well in Rhode Island, win in California, go to the top of the Gallup Poll, win the hearts and the minds of all Americans…

The end of Brown’s answer is drowned out in applause. Then he works his way through the crowd to join Andy Warhol. Warhol takes Polaroids of Brown while Earl McGrath and An Advance Man stand by.

ANDY WARHOL: I just need a white wall. That door is great.

EARL MCGRATH: Get up against that door! C’mon don’t stand there gabbing.

[snap/flash]

WARHOL: Could you do something with your hand the way you were doing when you were talking?

MCGRATH: Rub your nose. Hey, what are you going to do about New York City?

BROWN: I think we should all move to California. Where am I supposed to look?

WARHOL: Oh, just…

BROWN: Close my mouth right? Cover my dead teeth. Are we meeting with the Jackson delegates?

[snap/flash]

AN ADVANCE MAN: Yes, and we’ve got to make the 10:30 because there’re several deadlines we’ve got to make.

BROWN: I see. Is this a headshot?

WARHOL: It just makes a nice design. That’s good.

BROWN: I feel quite gimpy right now. That doesn’t quite make it.

MCGRATH: C’mon, Andy, do your imitation of Francesco Scavullo.

[snap/flash]

AN ADVANCED MAN: What I wanted to say to you was it’s better if these people locally send to Sacramento.

BROWN: Are we covered in Texas yet?

AN ADVANCED MAN: No, you’re supposed to do Texas right now.

BROWN: Well let’s do Texas! Let’s get Micky on the phone right now.

[snap/flash]

AN ADVANCED MAN: We know all about it.

[snap/flash]

MCGRATH: We know all about it. We’ve already called. Apparently it’s done.

AN ADVANCED MAN: Don’t worry about it, all I wanted to know…

MCGRATH: Send it yourself.

BROWN: I think you ought to pick it up. Pick it up, fly out and join the campaign before Tuesday. Why don’t you come out? We’ll go to Green Gulch on Wednesday and recalibrate—find out where the hell we go. I think we need a little Zen meditation to find out what the meaning of all this is. I’m the only candidate running for President without a clear sense of where it’s all going to end.

[snap/flash]

MCGRATH: And we thank you for that. You know that you don’t know.

BROWN: I told the people in Rhode Island to “pull the uncommitted lever for the un-candidate.”

AN ADVANCED MAN: Andy, we’ll see you later.

BROWN: Andy, I found your book interesting. It doesn’t seem to have that continuous flow. It was random.

MCGRATH: Like life itself.

WARHOL: Can we do one with a smile? Just one smile?

AN ADVANCED MAN: No, that’s Carter’s smile.

MCGRATH: He’s trying to do with his frown what Carter did with his smile.

BROWN: Yes, I’m the doom and gloom candidate. It’s all over, folks! It’s the end of the line. It’s all downhill, folks, but I may be able to pull us out.

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE JULY 1976 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.