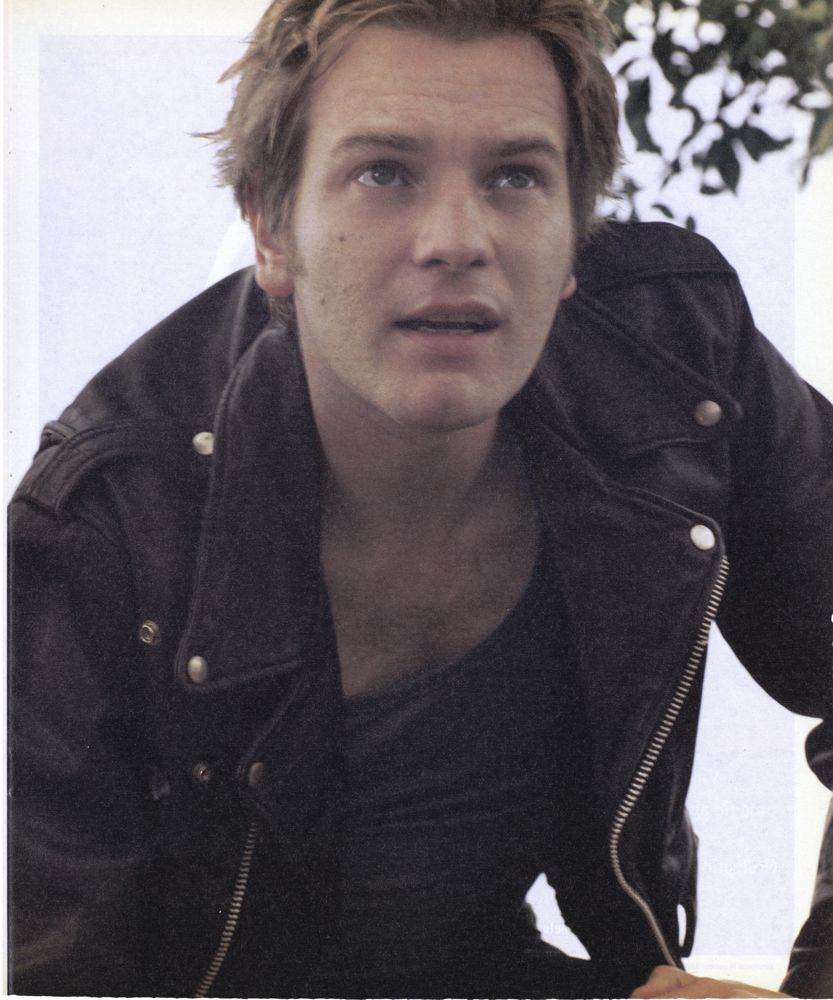

New Again: Ewan McGregor

Happy Burns Night! For those of you who don’t know, Burn’s Night is a Scottish tradition, a dinner held on the birthday of Romantic poet Robert Burns (Jan. 25), the man who wrote (the words to) “Auld Lang Syne” and a Scottish national treasure. Traditional celebrations involve the recitation of Burns’ poetry (including Auld Lang Syne as a farewell), toasting, eating haggis, drinking Scotch, and just generally lots of lovely stereotypical Scottish things that would warm the cockles of any eager tourist’s hearts. In the spirit of this festivity, we decided to revisit and interview with one of our favorite Scots, Ewan McGregor. We considered Tilda Swinton, but we ran into her last night and she said she wasn’t planning on celebrating the holiday (her boyfriend left his kilt back in England), so Ewan it is! We’ve spoken with Ewan several times, most recently at the premiere of his new film, Haywire, but we like this interview from 1998 the best. It captures McGregor at a pivotal moment in his career—just before his role as Obi-Wan Kenobi thrusted him from British film actor to imposing Hollywood star.

Ewan McGregor

by Todd Fuller

Why is Ewan McGregor such a big deal? It’s not just about looks and likability. The twenty-seven-year-old Scot has become a movie star by doing something a lot of his schticky, attitudinizing, careerist peers put low on their list of priorities: He acts

In the two years since Ewan McGregor played the heroin-racked Mark Renton in Trainspotting, he has become the most popular British actor of his generation. The reasons are not obscure. Cocky but unthreatening, soft-featured males have become movie stardom’s greatest currency in the postmachismo 90s. McGregor’s ascent parallels that of Leonardo DiCaprio and Matt Damon, actors whose maleness is emphasized, not diluted, by traditionally feminine traits like gentleness and passivity.

McGregor is more than a type, however. He acts with a refreshing lack of sturm und drang, shtick, or self-regard, and his effects are both minimal and effortless—the furrowed brow, the sly or incredulous gaze, the huge grin, the casual exposure of his heart and loins. He is equipped with neither the tortured genius of Daniel Day-Lewis, the fertile self-consciousness of Gary Oldman, nor the high-strung hauteur of Ralph Fiennes, but he has something of the young Albert Finney’s playfulness. One of the greatest assets is that he is invariably pleasing, whether he is being smug (Shallow Grave, 1994), swallowed by a toilet (Trainspotting), embossed with ink (The Pillow Book, 1996), a popinjay (Emma, 1996) or a working-class lad (Brassed Off, 1997). His eclectic choices—including several small roles in ensemble pieces—are those of a devout actor rather than a careerist. How much longer, though, will he be tempted to play dreamers? The test of McGregor’s range will surely come when he is asked to espouse authoritarianism or evil, but it wont be in next year’s Star Wars: Episode 1, in which he steps into Alec Guiness’s shoes as the young Obi-Wan Kenobi.

While in drama school, McGregor got a vital break when he was cast in Dennis Potter’s miniseries Lipstick on Your Collar (1993) as a war-office clerk who gets through the Suez Crisis by fantasizing about being a rock and roll crooner. This month, in Todd Haynes’s glam rock memorial Velvet Goldmine, he takes rock theater to a different level with his ballistic portrayal of American protopunk Curt Wild, a thinly veiled Iggy Pop. It’s McGregor’s most primal performance yet—and his bitterest. He is currently taking a break from movies to appear on stage in the Hampstead Theatre Club’s production of Little Malcom and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs, directed by his uncle and occasional mentor, the actor Denis Lawson. He can next be seen onscreen as a sweet, gormless pigeon fancier enamored of Jane Horrock’s closest diva in the December release Little Voice; it’s another role for the twenty-seven-year-old Scot that is more about acting than ambition.

GRAHAM FULLER: Have you ever fantasized about being a rockstar?

EWAN MCGREGOR: Always, so Velvet Goldmine was an opportunity to get it out of my system. Of course, it didn’t work. I thought it would expel the rock-‘n-roll demons, but it just put more of them in me.

FULLER: What did you now of glam rock going in?

MCGREGOR: I was born in ’71 so I remember bits of glam rock on Top of the Pops toward the late ’70s, but I had no idea what kind of world it was. I didn’t like the music either. Not particularly fond of it now, either, except for Iggy Pop’s stuff. I think the sound was specific to the era and I kind of didn’t get it. Nor did I understand why they were wearing all those strange clothes. I certainly didn’t listen to hours and hours of glam rock to get into the part.

FULLER: Did Todd Haynes tell you that the inspiration for Curt Wild and Brian Slade [played by Jonathan Rhys Meyers] was specifically Iggy Pop and David Bowie, or was that an assumption you were left to make for yourself.

MCGREGOR: Whether the love story is their story or not, I have no idea. Simply in terms of British glam superstar, it’s clear who Brian Slade is. Curt is made up of bits of different American rock stars, so he’s more general. None of this was secret.

FULLER: How conscious were you of playing Curt as Iggy?

MCGREGOR: My look—with that long, bleached-blond hair—and certainly what I did onstage was Iggy. I looked at film of him performing to get that mad physicality. I looked at tapes of Lou Reed, and Robbie Robertson in The Last Waltz to try and get that fucked-up, groggily rock-‘n’-roll voice. The way it reads in the script, Curt has to come out with a bang when Brian Slade and the audience see him for the first time. After a couple of rehearsals my lungs were coming out and when I got up to do the first take, I was worried I wasn’t going to make it through the number because I’m not very fit. But as soon as the camera started turning, I stopped worrying because this mad stuff started happening. I guess from watching Iggy Pop I’d sensed what kind of state he gets into; it’s like something’s inside him and he’s got to shake it out of himself. And if he falls over, he doesn’t even recognize it; he just gets up and carries on. That’s what I feel like, too.

FULLER: It looks like you went into a different space.

MCGREGOR: Oh, I completely lost it. I didn’t have a clue what was going on until they said cut, and then I was going, “Whoa!” I’ll never, ever forget what it felt like.

FULLER: Iggy would cut himself with razors onstage and smash the mike into his teeth, and there were rumors of blow jobs—given and received. How far did you think you’d be able to go in a movie?

MCGREGOR: He always had his cock out. He’s very fond of his penis, I think; I’m rather fond of mine too. It made sense to me that he’d always be whipping it out. There were only four hundred extras there when I did it, so it was a different ball game. But to stand there with your trousers around your ankles, there’s something about it … I don’t know quite what, but it didn’t feel at all out of place. It was a powerful feeling, in fact. Todd had written in the script that Curt turns around and moons the audience. I’d seen Iggy Pop do this thing where he stood stock-still, staring at the audience with his hands down the front of his trousers. And then he started to jig about and his trousers fell down as he was dancing around. I thought I’d do that but I ended up pulling my willy around and sticking my head between my knees. I had no idea that was going to happen and the camera crew certainly didn’t. I’ll never forget their faces after the first time.

FULLER: Do you have views on what the film’s got to say about sexuality?

MCGREGOR: It’s about freedom, isn’t it? And being yourself, and being even more than yourself, and just going for it. But the film displays a debauched and selfish time and it leaves you with a sour taste in your mouth because so many of the people end up dead or fucked-up or unhappy or lost. Perhaps that’s irrelevant, though. I watched this documentary about a photographer [Nan Goldin] of the New York gay scene in the ’70s and ’80s. She said she took photographs because otherwise she wouldn’t remember where she’d been, so they were like her pictorial memory. Then when AIDS kicked in, her photographs went from being a record of the massive, happy energy of that scene into memories of her friends dying. In a way, Velvet Goldmine‘s like that. I still don’t know why people are so reluctant to talk about the ’70s. What was going on that we were running away from? Look at film of Ziggy Stardust onstage—how can their be any doubt about what image David Bowie was trying to convey? And why shy away from it now?

FULLER: Bowie has always woven his way between categories because h wants to be unknowable; he’s too smart to be pinned down. I suspect it’s because he wants to preserve some mystery. That’s why he killed off Ziggy onstage in 1973, before he became a self-parody, which is exactly what Brian Slade does become in Velvet Goldmine. The Ziggy movie Bowie’s planning could contradict all that, of course.

MCGREGOR: Is he going to play Ziggy himself? [laughs] Could be weird. It should be some new guy.

FULLER: I heard Velvet Goldmine was a tough shoot.

MCGREGOR: I only did four weeks on it and I’m quite glad about that because I might have gone over the edge to rock stardom. Also, we worked insane hours. Making movies gets more and more like that, and I despise it for the crew’s sake. We were fucked around right and left on this one. The finished movie really works and that reminds you it doesn’t always have to feel rosy when you’re doing it. Producing good stuff can be quite tough and it involves a lot of frustration, but I always like things to be jolly and happy, and I forget that’s actually not the point at the end of the day.

FULLER: Are people treated badly on movie sets in your experience?

MCGREGOR: Such shite goes on. Producers blatantly fuck over the crews. Maybe I’m naive and should just get used to it. I saw an interview with James Cagney, and he was talking about the old Hollywood days. He said, “We were shooting thirteen, fourteen hours a day, six days a week, and it was just getting too much.” I was like, “Fucking hell, James. That sounds like an easy life to me.” A sixteen-hour day is normal these days. But how can crews be expected to work sixteen hour days with no overtime and then have to pack up and drive two hours home? And then they’re expected to be bright and breezy and supportive the next morning. I find the more I do the more I need to be involved with the crew—I need them to be there with me. If I’ve got to do something really difficult or risky with half of them hanging onto the light stands, it’s impossible. So I’m using what clout I’ve got to do something about it if I think they’re being badly treated. We actually lost a lighting crew on Velvet Goldmine, three weeks in. I don’t quite know why, though. I don’t think they liked that we were filming men fucking each other up the arse on a rooftop in Kings Cross. God, I’m sounding really jaded now. I don’t want to appear that way.

FULLER: Are you jaded?

MCGREGOR: No, but I’ve had enough of making movies for a while. It got to the point where they’d come to call me on set and I’d buckle under, and I don’t want it to be like that. Working on films back-to-back, I began to find I was losing myself to the extent that I’d completely forgotten what it was like to get up in the morning and sit and watch the telly. And I didn’t have a bath for two years because I didn’t have a fucking tub. I try not to moan about it because it’s unusual for an actor to be in so much work, but it does bring its own pressure. The worst part of it is that I haven’t been able to develop the same kind of relationship that my wife [Eve] has developed with our daughter [Clara]. She’s only a wee one and I usually only get to see her when she’s asleep. So I’ve been taking a break recently and it’s been good to get that relationship back.

FULLER: How was the Star Wars experience?

MCGREGOR: It was a mixture of exciting and boring. Every day there’d be a few moments where I would go, “Fuck, we’re doing Star Wars.” But it was also a tedious film to make. There’s not a lot of psychological stuff going on when you’re acting with things that aren’t actually there.

FULLER: Was it bizarre playing Obi-Wan Kenobi?

MCGREGOR: Very weird. The Jedi Knights have got a sense of what’s going to happen, so they don’t freak out or panic or anything. But after a while I noticed the only thing I was doing was frowning a lot. That’s a worry when you shoot for three-and-a-half months.

FULLER: Did you encounter the Hollywood machinery?

MCGREGOR: No, because most of George Lucas’s people are based in San Francisco and didn’t get involved—I liked them for that. I used to bang on a lot about how disgusting it is that massive amounts of money are spent on movies and then I took a part in Star Wars. Never mind. But what I want to do in the future is more films like Velvet Goldmine and Little Voice because I think they’re better films than most of the big ones. The less money you have, the more exciting the work is.

FULLER: Is it important for you to stay in touch with the original impulse you had to be an actor?

MCGREGOR: Yeah, but it’s almost impossible. With everything you end up doing, you go somewhere else. I still have a passion for acting, but some of it was beginning to disappear, which is another reason why I’m taking a break right now. I felt I was getting a bit lazy. I’ve never found acting that difficult. If you ask me, it’s all rather easy if you keep it simple. But as soon as you lose that original drive, it’s not fun. That’s why I’m returning to the stage. I want to remember what it’s like to be really frightened again. The fear of being crap is always what makes you good, I think. Then when I get back into films, I’ll go at it hammer and tongs.

FULLER: Is it possible to say what all this has done to the inside of your head?

MCGREGOR: It’s quite confusing. Success is tricky to deal with, both professionally and in your personal life. At the same time I still want more of it so I can sit there and see myself come up onscreen. I never quite believe it’s me up there and I can’t quite describe how good it feels, even if it’s not a very good film. It’s in my dreams and there it is.

One month later…

FULLER: Of all the films you’ve done, the one that reverberates in people’s minds is Trainspotting, which was funny and exciting but didn’t gloss over the misery of junkiedom. Was playing Renton in that film important to you?

MCGREGOR: He was like a Christmas present. It was the kind of part you only get once in a while. I’d been waiting for him to come along and when I read the script, I thought, Well, here he is—here he comes. For months beforehand, I though about nothing else, and I threw myself into it 100 percent and played him with a passion.

FULLER: I’m curious to know how much you identified with him—I don’t mean as a junkie, but as a young, urban Scot. There’s that scene in the movie when Renton and his friends take a train to the edge of the Highlands, and Renton trashes the image of Scotland that’s marketed to tourists, that whole tartan thing.

MCGREGOR: Yeah. Shortbread.

FULLER: Is that how you feel about it, too? I know you go back to Scotland a lot.

MCGREGOR: In the movie that’s just a bunch of angry guys who don’t want to be in the countryside, who don’t want to do anything or be anything really. I can understand their sentiment that it’s shite being Scottish because we’re ruled by England, but maybe that’s changing now—I don’t know. I love Scotland. It’s so much a part of who I am. My parents and family live up there so I naturally want to visit a lot. I miss the land and the people when I’m away. We’re quite a proud race, and I’m as proud as anyone to be Scottish.

FULLER: It’s heartening to see you in Little Voice, which is a tiny English movie with more life in it than most of the movies I’ve seen this year.

MCGREGOR: Mark Herman directed me before in Brassed Off. I was impressed with what he did with that film, and I think it was an important film for Britain to see because it showed the mining communities being torn apart. I was worried that Miramax might slaughter the politics in it and turn it into a love story, which, to their credit, they didn’t. I also liked playing in an ensemble like that. Little Voice was the same kind of idea, and there was a fantastic wee part in it for me.

FULLER: You’re happy playing ordinary guys?

MCGREGOR: I’ll play anyone or anything.

FULLER: A lot of movie stars only play heroes.

MCGREGOR: I see my job as very simple: I have to pretend to be different people. So, to make it interesting and to live up to my job description, I should pretend to be different people all the time. They must never fall into the same category. And because I’m an actor, it’s not about me. If I was worried about my image, or if I was always playing somebody who saves hostages from airplanes, I wouldn’t be in this business at all. I’m not worried about how I come across in a film, as long as my character serves the story. I don’t care what people think about me.

FULLER: How come you’ve never hired a full-time publicist?

MCGREGOR: Because I don’t like to be in the press. People say you have publicists to keep you out of the press, which is bullshit. If you want to keep out of the press, just don’t speak to them. There are actors everywhere, a lot of them in Hollywood, who instead of pursuing good acting and making good films thrive on being in magazines and making sure they’re in the right ones and at the right parties with the right people; in fact, that seems to be what Hollywood thrives on as a whole. I’ve always detested that side of the business. I’ve worked with too many people who find the acting part of it slightly boring, but they do it because it’s the part that allows them to become famous. For me, the magazines and the photos shoots are the boring parts of my job that allow me to be on set doing my work. I’ve had to hire a friend to handle the publicity for me when Star Wars comes out next year because I know that’s going to be a major one. On the whole, though, I’ve never really understood what press agents do. They charge you quite a lot of money, and I’m reluctant to give anyone my money. [laughs] It’s the same argument with managers: What do they do? It seems they’re there to book theater tickets for actors, and I can book my own. They want 15 percent, then your publicist wants 15 percent, and it all adds up. I just think they’re leeches and I can do without them.

FULLER: So it’s acting and nothing else?

MCGREGOR: I’m not saying some of the other stuff isn’t fun. But the biggest kick I get out of my job is to be on set when the camera’s turning. That’s the most exciting thing in the world for me. I always find it frightening walking on a carpet with banks of photographers on either side. That’s just part of the machinery that’s selling your image to make money for the film. People get carried away with that because everybody’s really fascinated by movie stars. They think they’re all fantastic human beings. See, in my experience, most of them aren’t. [laughs]