FAIR

Meet Shanzhai Lyric, the Art Collective Celebrating New York City’s Digestive Tract

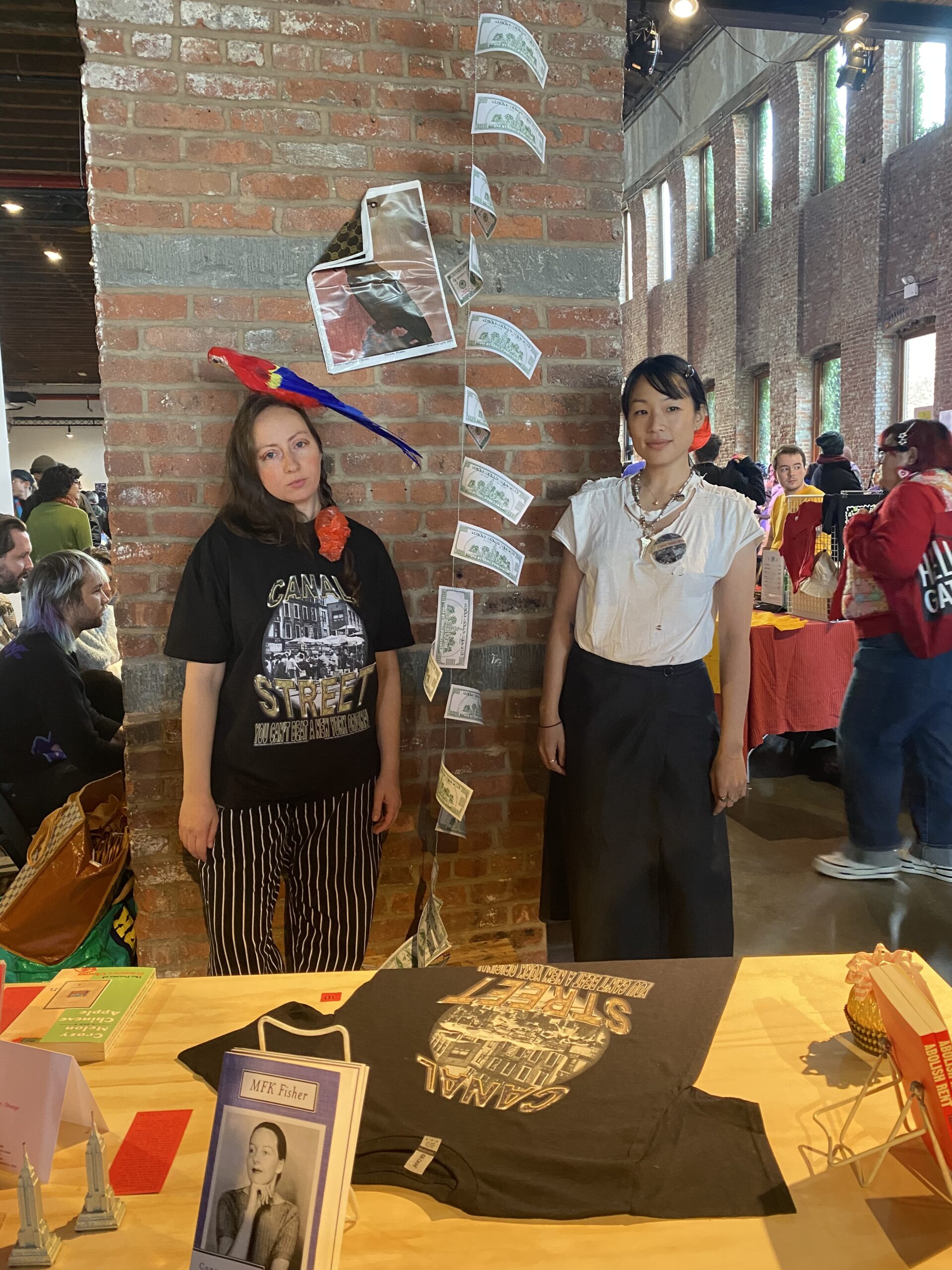

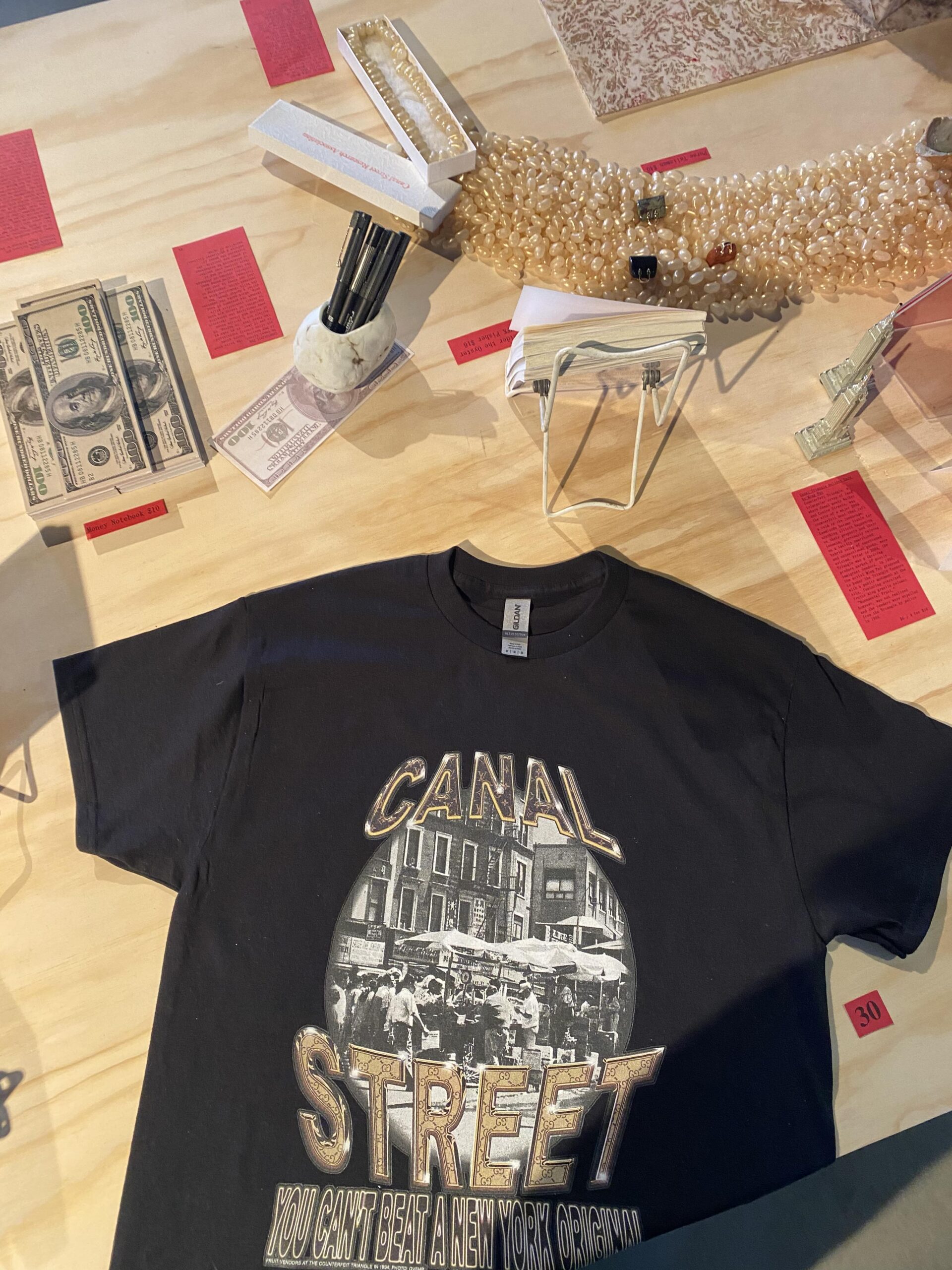

Just blocks from the Interview office, the art collective Shanzhai Lyric has been conducting their rigorous study of Canal Street, or what they lovingly refer to as New York City’s digestive tract. Childhood friends Ming Lin and Alex Tatarsky originally set out to research nonsense poetry on bootleg t-shirts at a multi-level women’s clothing market in Beijing. But when Covid disrupted their plans, they found themselves back in New York on Canal, where they both grew up. Inspired by this new landscape and their consistent proximity to counterfeit markets, they created the fictional Canal Street Research Association to document their neighborhood and continue ruminating on their obsessions: accidental poetry, the art of the luxury knockoff, and the forces of global trade that converge along one of New York’s oldest streets. With a residency at Green-Wood cemetery on the horizon, we met up with Shanzhai Lyric at their booth at this year’s iteration of Press Play, Pioneer Works’ annual publishing fair. In the back of the Red Hook warehouse, teeming with lovers of small press poetry and esoteric tchotchkes, we took a strategic coffee break to discuss parrots, piracy, and the profundity of the plastic bag.

———

JULIETTE JEFFERS: Start by sharing how you two met and formed this collective.

SHANZHAI LYRIC: We met growing up in Lower Manhattan as childhood friends. Shanzhai Lyric started in 2015 in Beijing where we were researching nonsense poetry on t-shirts at a multi-level women’s clothing market called Zoo Market. That’s where we began gathering these phrases, what we came to call Shanzhai Lyric, which we consider an ever-growing poem expanding across bodies and landscapes. Since then, we have started archiving these poetry garments.

The whole concept is inspired by the notion of Shanzhai, the Chinese word for counterfeit, but which literally translates to “mountain hamlet” and has a liberatory notion attached to it as opposed to the more derogatory “counterfeit.” We thought about Shanzhai as a philosophy, a politic, and a poetic mode. We wanted to dig deeper and trace a single poetry garment around the world to understand the mechanisms of this collective authorship–the collaboration between many human hands and machine technology that create these beautiful, often oddly insightful aberrations.

We were excited to follow this garment around, but then the pandemic happened. Stuck in New York City on Canal Street where we both grew up, we founded the fictional Canal Street Research Association to study those same global trade flows as they coalesced on one block of Canal between Mercer and Greene. We went there every day to sit, associate, and create an intriguing environment. We made a fake office to lure curiosity seekers to talk to us about the block, New York City’s bootleg epicenter.

JEFFERS: It’s interesting what you said about the freedom of language with counterfeit t-shirts. You’re not constrained by the reality of common English phrases. I read about how you walked Canal Street, documented the storefronts, and interacted with people selling counterfeit bags. As you described, Canal really feels like a cross-cultural global epicenter.

SHANZHAI LYRIC: Yes, Shanzhai comes from a Song Dynasty novel called Outlaws of the Marsh, a Chinese Robin Hood story of stealing from the empire and redistributing among people on the margins. We conceived of Canal Street as Manhattan’s buried marshland filled with noble outlaws working unofficial economies and hustles. We also learned Shanzhai has origins in Chinese landscape painting, which has a different relationship to authorship. A painting accrues value the more people co-author the landscape together. Landscapes often leave emptiness to invite collective inscription. One feature of our fake office was a photo of every Canal building that we tacked on the wall, inviting anyone to add their inscription, co-authoring this landscape with us. That’s how we encountered many Canal Street histories we’ve been working to share. For example, we learned about Paul R. Paradise, a foremost scholar of trademark law. Looking up his work, he has literature on that subject alongside a whole body on training and keeping parrots.

JEFFERS: It’s all about mimicry.

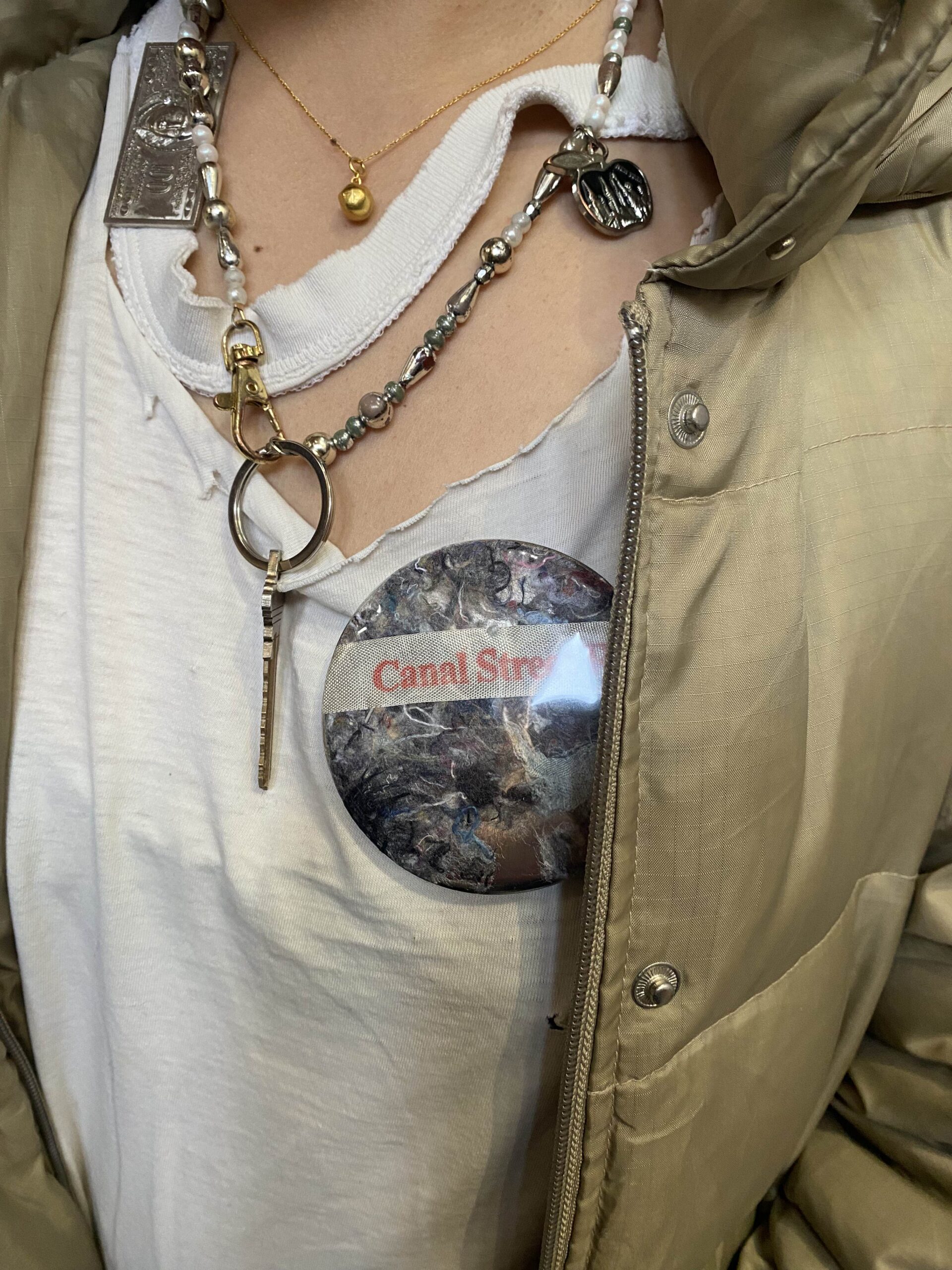

SHANZHAI LYRIC: Exactly, he’s interested in the maintenance and regulation of mimicry. So this year we were invited to be artists in residence at Green-Wood Cemetery, which happens to have New York City’s largest population of monk parakeets. They’re an alien species but have lived here for decades. We’ll have the archive with us in Green-Wood for a year-long residency. We’re hoping to work with the parrots as well, and the bag we made for Press Play is inaugurating that phase of the research.

JEFFERS: Tell me more about the bag and your scrunchies.

SHANZHAI LYRIC: The bag relates to our interest in plastic, a big part of Canal Street history. Many artists have lived and worked along Canal Street—you could say it’s the seat of 20th century art history. Artists came for access to raw materials, including the many plastics stores that used to line Canal. Only one is left. We wanted to make a plastic bag to honor it as a precious material that should be reused. We thought about the performance of ecological care in phasing out plastic bags for supposedly reusable totes, which actually take more energy and materials to create and are still often treated as disposable. It’s an empty gesture when there are long-standing practices of saving, collecting, and reusing plastic bags, mostly among immigrant communities and people with creative relationships to items considered not valuable. We both grew up in plastic bag-hoarding families and felt like it was important to surface these existing circular economy practices. The logic behind the red plastic bags, an iconic feature of the Chinatown portion of Canal Street, is that plastic bags are print objects where interesting commentary and design already circulate. We should cherish these items, not throw them away. The plastic bag brings into contact the two subjects of our current study: pirates and parrots.

JEFFERS: Canal Street used to actually be a canal. If Times Square is the heart of New York, what vital organ would you say Canal Street is?

SHANZHAI LYRIC: Maybe the digestive tract. It’s a channel that accumulates, processes, and expels waste, serving that function for a long time, a symbol of ongoing cycles in New York City. Since the beginning of the colony, Dutch and English settlers used the canal as a dumping ground. Where it had channeled water from a large freshwater reservoir, it became a garbage disposal. In many ways, we still treat our waterways that way.

JEFFERS: It’s interesting how it has retained that feeling over the years.

SHANZHAI LYRIC: Because of its sinking and stinky nature, many marginalized populations have been relegated to that area. But your question makes me think about bodies of water in relation to our bodies. As we increasingly discuss, the gut controls so much of how we feel and think. It feels important to care for the city’s gut.

JEFFERS: Totally. There’s a rich history of artists on Canal Street. The Interview offices are on Canal, which is crazy. I spend a lot of time there, and when I go into the office, there is something Warholian about emerging from the subway and immediately seeing all these knockoffs. It is very beautiful. What originally drew you to the knockoffs?

SHANZHAI LYRIC: It started with the language of “counterfeit” t-shirts. When we went to China to begin this study, that language already had an audience, sometimes referred to as “Chinglish.” But we felt that had a mockery or judgment attached and didn’t encapsulate how beautiful, irreverent, and sensible those phrases could be. That prompted us to think about a different way of framing it. We have an archive of over 400 poetry garments that circulates as installations in different archives, libraries, galleries and museums. The Shanzhai t-shirts helped us think about bootlegs as commentary and critique, reframing our view of bootleg luxury bags and items we grew up with and grew up loving. One delicious Canal Street factoid is that Duchamp allegedly found his famous urinal on Canal. The history of the ready-made art object can be traced to Canal Street. Part of our practice has been situating the bags as ready-mades in that lineage. One ambition before founding Canal Street Research Association was to go to the Museum of Counterfeit in Paris, a weird small museum helmed by LVMH working with French border patrol guards.

JEFFERS: So they confiscate stuff and bring it to the museum.

SHANZHAI LYRIC: Yes. It brings into relief how definitions of real and fake play into border maintenance and nation-states.

JEFFERS: It’s a huge economic draw. So many people come to New York to buy fake bags every day.

SHANZHAI LYRIC: The vendors often talk about themselves as unpaid advertisers, cognizant of the dynamic where no one will get rid of the unofficial markets. It’s a game of cat and mouse with regular raids, making the cops look like they’re doing something. There’s an understanding the markets will come back the next day. The luxury corporations rely on the vendors to share the latest fashions and stoke product desire. They’re in an intimate relationship, often manufactured in the same factories as the originals. That’s what’s exciting about Canal Street and the street markets—it points to the artifice of these definitions and categories. It’s often who’s profiting that determines whether something is considered luxury rather than the actual quality.

JEFFERS: You really found a physical space to bring everything together: mimicry, these global economic forces, and what you share from childhood. So what’s next?

SHANZHAI LYRIC: We’ll keep thinking about all this stuff. Along with rethinking discarded materials, we created a shoddy badge for the fair, trying to reclaim the material shoddy, a textile made from discarded cotton and wool that used to be popular. But cotton and wool industries framed shoddy as poor quality because they were afraid it would take away their profits to have a viable recycled textile. We’re trying to celebrate shoddy in connection to the Canal Street area. We’re ALSO starting a year-long inquiry called Ragpickers Court. The shoddy badge is inaugurating that, but we want to bring shoddy to the surface also in connection to celebrating gleaning communities involved in upcycling, recycling, repurposing materials, trash-picking, and canning. One of the big trash-picking communities now is our canners who collect cans for redemption. We don’t exactly know what it looks like, but it will be ongoing.