New Again: Anthony Hopkins

In New Again, we highlight a piece from Interview’s past that resonates with the present.

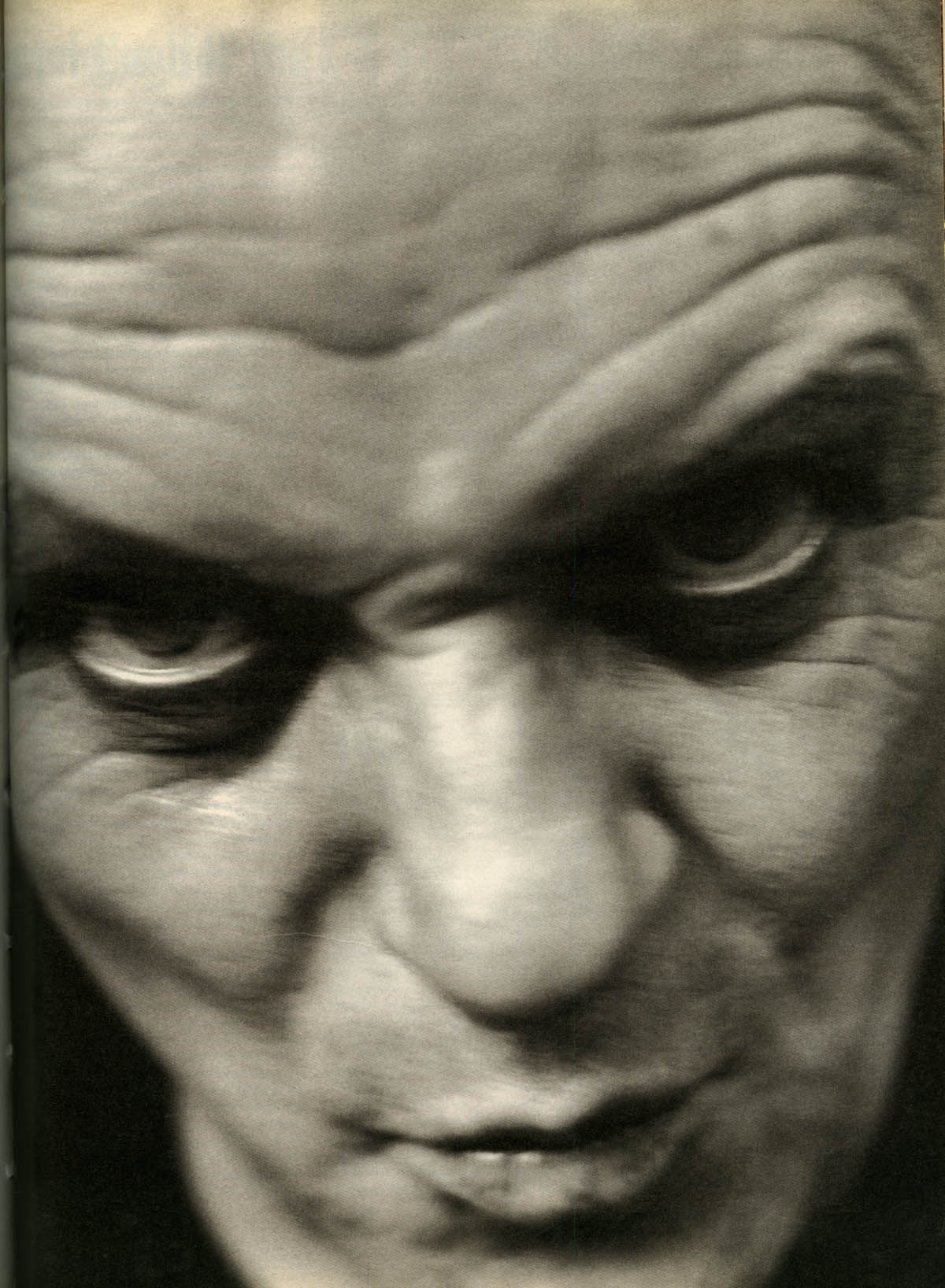

The Silence of the Lambs turns 20 this year, and an ample dose of reinvention is promised in 2012. NBC bought the rights to a Hannibal Lecter series, and no retrospective of the bluntly terrifying yet vaguely endearing cannibal is complete without reference to Anthony Hopkins’s 1991 portrayal.

The man who has played Hitler, a psychopath-ventriloquist, and a handful of Shakespearean curmudgeons earned an Academy Award in 1991 for his portrayal of cannibalistic serial killer Hannibal Lecter. To commemorate Lecter’s revival (and because we also have a soft spot for Jodie Foster), we revisit Lisa Liebman’s interview with Hopkins in our March 1992 issue. Hopkins talks good, evil, and even divulges secrets about Mickey Rourke and a few of Hollywood’s most enigmatic directors.

—

There is no arguing that on film, stage, and television, Anthony Hopkins is one of the best actors working anywhere today. Extremes of good and evil have, to an unusual degree, colored Hopkin’s career. His nuanced portrait of the Nazi camp criminal Kelno in the ABC miniseries QVII saved what might have otherwise been a ham-fisted TV drama. In The Tenth Man, a CBS version of Graham Green’s novel, Hopkins created one of the more interesting spies to come out of the cold since his fellow Welschman, Richard Burton, essayed Le Care in 1965. Hopkin’s film roles include Corky, the psychopath-ventriloquist of Magic, the gentle Dr. Treves in The Elephant Man, Captain Bligh in The Bounty, and the timid London bookstore clerk and the great epistolary love of 84 Charing Cross Road. He has also played Hitler in The Bunker. But it was his glinting, steel-trap performance as Hannibal Lecter, the evil genius of Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs, that made him Hollywood’s “leading Brit”- a role about which he is quite sanguine.

Our appointment was on the morning of Thursday, October 10- an appropriately sinister date, in numerological terms, and a meteorological freek as well: the mercury climbed toward 100 F. Fires broke loose in Northern California over the following weekend. Nonetheless, we lingered over breakfast in a well-padded sanctum of the Westwood Marquis hotel. At noon, floating like helium balloons in the astonishing heat, we headed for the UCLA campus, where Hopkins had been invited to speak: a Lecter sound bite on request, and an understandably staunch objection to capital punishment. By two o’clock, we returned for lunch, chaperoned as before by the urbane Bob Palmer, Hopkin’s friend and publicist.

LISA LIEBMAN: I just saw Magic a couple days ago. You play a ventriloquist with a foulmouthed dummy, and Burgess Meredith is your manager, an old-time show-biz character. At one point, when your nightclub act seems to be catching on, he says to you, “Will ya try not to turn shit-heel? That’s almost an automatic once a guy makes it big.” Have you recently thought of those lines? Has your life changed since The Silence of the Lambs?

ANTHONY HOPKINS: No. I suppose I’m happier. More at peace. It’s nice to be in a big hit.

LIEBMAN: Does L.A. seem very different to you now from when you last lived here?

HOPKINS: I don’t actually live here now. I’ve got to be here for four months, for Dracula. But I’m living at a hotel in Santa Monica.

LIEBMAN: Are you married?

HOPKINS: Yes.

LIEBMAN: Is your wife here?

HOPKINS: No. My wife used to be in the film business, but she isn’t any longer, and she hates Los Angeles with a passion. I’m trying to convince her to come at Christmastime, because we’ll be in production then. But I don’t know if she will.

LIEBMAN: She’s English?

HOPKINS: Yes. She is living in our house in London. I lived in America for ten years, from 1974 to 1984, and she’d had enough of it by then.

LIEBMAN: Do you have children?

HOPKINS: A daughter, Abigail, from my first marriage. She’s twenty-three and wants to be an actress. She’s here now. She’s been going all over America. She’s having a wonderful time.

LIEBMAN: Do you approve?

HOPKINS: I don’t believe in nepotism. I don’t much like the idea of parents who interfere. I hope she finds herself. She wants to be everything- a writer, singer, dancer- and she’s something of a spiritual quester.

LIEBMAN: What about you and the California life?

HOPKINS: California has done a tremendous amount for me. I love living here…

LIEBMAN: So what happened in ’84? What prompted you to move back?

HOPKINS: I never thought I’d work here again. There’s a divide. English actors tend to come and go, you know. America’s been very good to English actors, but it’s not the same. I had been doing The Bounty, and I enjoyed it in some ways. I enjoyed working with Mel Gibson- he was nice- and especially Dan Day-Lewis. The role of the Bligh in The Bounty is actually one of my favorite parts. But it was done in Tahiti, and it was rough working on the ships. People were very sick. Not me so much, but if you work on boats all day, there’s a strong chance of sunstroke. And all the waters were dirty. There were so many takes, you didn’t know what was happening. Then I returned, and at the time I didn’t get, you know, the sort of Robert De Niro offers. I wanted to do something, and I thought maybe I should go back and exercise my brain. So I went back to the theater and I did some American films in Europe, and I did The Tenth Man for CBS. But I’d really thought I’d vanished off the American scene. So it was a surprise when Jonathan Demme asked me to do Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs.

LIEBMAN: What made him want you for the part?

HOPKINS: I think it was The Elephant Man that did it. I had also done M. Butterfly, in London, which I think he came to see.

LIEBMAN:Did you have a concept for Lecter or did you find the character as you went along?

HOPKINS: Yes, I had a concept. I conceived of Lecter as a clicking machine. A killing machine. So much was shot in extreme close-up to get the sense that Lecter was living in another world that I had to play a lot of scenes straight into the camera, which was often just a couple of inches away from my face, or sometimes ot the script girl right behind it, which was fine but a little frustrating. As a director Demme talks to you a lot. He looks at you very earnestly and describes what he wants. Then he goes and looks through the viewfinder or the TV monitor, and starts saying encouraging things: [Hopkins vogues for a second, like a fashion photographer] “Yeah, yeah…that’s great.” That sort of thing.

LIEBMAN: What about Lecter’s soft spot for the Jodie Foster character, Clarice?

HOPKINS: He’s still human. I played Hitler once, and at one point I was approached by on of the film’s producers, who actually said to me, “That’s nice, but could you just play him less human?” Well, Hitler is human- that’s what’s frightening. Clarice taps into Lecter’s sense of humor. He finds it amusing that this little nothing of a girl….It’s a fairy story, you see, in which the heroine goes into the cave of the Wicked Dragon. I conceived of it as a fairy tale, as a spiritual archetype of good and evil. She shines the light into the darkness and it helps her see her own demons. He arms her to trap the real dragon. I have great hopes, by the way, that Hannibal Lecter will return.

LIEBMAN: From the Caribbean, where we last saw him?

HOPKINS: Yes, perhaps- a refreshed man. I’m just waiting for that wonderful author (Thomas Harris) to finish writing another book. I’ve been told that he’s doing just that.

LIEBMAN: Do you think about good and evil when playing your most wicked parts?

HOPKINS: We’re all caught up in circumstances, and we’re all good and evil. When you’re really hungry, for instance, you’ll do anything to survive. I think the most evil thing- well, maybe that’s too strong- but certainly a very evil thing is judgment, the sin of ignorance.

LIEBMAN: Is there any part you’re dying to play?

The big blue eyes drift upward at this point, and Bomb Palmer, long quiet, interjects. “A remake of Shane,” he says, “would be nice.” And we ride off to the star-struck UCLA campus. Later, back at the Westwood Marquis, everyone goes to freshen up, and Hopkins returns to our table holding a few dried petals between two fingers. Quite rapturously, he sniffs them, then offers a whiff. “Potpourri,” he says, “from the men’s room. It’s lovely, isn’t it? It’s peach”

LIEBMAN: Tell me a bit about Howard’s End.

HOPKINS: It was lovely to work on. A very peaceful set. Emma [Thompson] is a lot of fun. She’s wonderfully- very talented and enormously entertaining all the time. [Vanessa] Redgrave, of course, is very serious about work. I enjoyed working with [the director] James Ivory. Jim is more remote, a bit distant- I don’t think he’s particularly affectionate man. He doesn’t really tell you how to do much. He’s a very visual director. He sits there quietly a lot, almost like a sketch artiest, and has an amazing ability to direct several things going on at once in a scene- you know, the way two people may be talking whilst someone else may be moving in a vase or something around, and someone else might be walking into the parlor. He has a very powerful sense of the way people actually ive, what they do in their own houses, and how the houses ought to look. He likes things to look just so. He’s very American in a sense, but he’s an Anglophile.

LIEBMAN: What class of Englishman is your Mr. Wilcox?

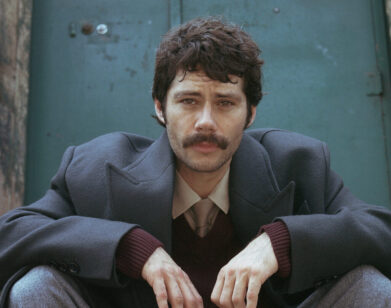

HOPKINS: I had a strange attitude about Wilcox. I sort of kept my mind detached. He’s not based on any particular person. In hindsight, I guess, I can say he was a man trapped in his own ego. All he understands is business. He was from a class of people- the gentry, the burgeoning upper middle class- the worked at building a business and was quite involved in hierarchical structures of society. Things haven’t changed that much in England at all. There’s still great resentment against those who succeed and rise. They prefer it if you fail. You’re supposed to stay in line. I didn’t do anything “psychological” preparation or anything. I think it was the mustache that helped me with the part. Jim Ivory asked me one day if I wanted a mustache. At first I said, “No, I don’t think so,” but then I put it on and that was that- the upper lip.

LIEBMAN: You’re Welch, aren’t you, not English?

HOPKINS: Yes. I come from Port Talbot, the same part of Wales as Richard Burton. At a quite early age I knew: there was nothing there for the future.

LIEBMAN: Did you realize you were an actor early on?

HOPKINS: I became an actor quite by accident. I couldn’t do anything else very well. I was an only child and very shy- a miserable student, very introverted. No confidence. I spent two years in the military service, then I trudged around in repertory for quite a while. I somehow wound up at the National Theatre, though, and then I was definitely on my way. It was Laurence Olivier’s theater and I got to play Macbeth and Coriolanus and Atony and Lear. I played Lear twice, actually. Once when I was about twenty-sex, and again at forty-eight. The second time was very difficult. Onstage, this little voice would tell me, “What are you doing here?” It took twenty-five or thirty performances to begin to understand how to play it. It’s an easier part to play, I think, either very young or very old.

LIEBMAN: Did Olivier ever direct you?

HOPKINS: He directed me in The Three Sisters and in Juno and the Paycock. He was a very organized director. Very disciplined. I was at his funeral. I read the last four lines of King Lear.

LIEBMAN: What have you done on stage that you’ve enjoyed in the States?

HOPKINS: Well, I did Peter Shaffer’s Equus, which was something of a success. And in California when I was living here I did a Tempest. I had been loafing around between films. I was having a good time, but I wanted to do something.

LIEBMAN: Do you miss theater?

HOPKINS: I don’t have a vast longing for the stage.

LIEBMAN: That’s sort of refreshing. And what do you and don’t you like about making movies?

HOPKINS: I believe I am quite amiable and affable and quite fair, and I’ve rarely worked with people who are the opposite. Moodiness scares me. It’s all controllable, you see. What gets to me is unkindness. Madness. Unwarranted cruelty through words. People who scream and shout at work. I hate confrontation and violence. I’ve done it in the past and I don’t want to do it again. I guess I want a perfect world. But I like to work. I don’t like to disrupt my equilibrium. I don’t like to change my head. I’d rather be a third-rate actor. It’s a job, and I’m dedicated in my way. I enjoy it. I’m serious about it. But if it doesn’t come off, I’m not going to die. I used to have to live it and sleep and eat it. But now I don’t want upset, discord. I know actors who play a violent part and are vicious on the set. Mickey Rourke was like that a bit [on Desperate Hours.] I dreaded going on the set. Every day I went on a wing and a prayer. I would go up to people on the set of The Elephant Man and say to them, “I hope you’re having pleasant dreams.” Then I’d wonder, What do I do next? David Lynch was the director. It was weird- you’d get the sense he was living in another world.

LIEBMAN: What part about making movies do you like the best?

HOPKINS: I love the hour in makeup. It gives you time to think and have a cup of coffee. It’s my favorite part of the day. Having somebody dab things on your face- I love that. Then you go out and say things and they pay you. It’s a nice line of work.

LIEBMAN: How are you enjoying work with Coppola?

HOPKINS: He’s a wonderful fellow. You’re aware that he’s dangerous, in the sense of volatile- you know, he’s creative, he’s Italian. If you do something outrageous, he’ll jump up and down. He looks like an opera singer. Often he doesn’t now what he wants. He likes chaos, gunpowder, but I’m enjoying the chaos now- I didn’t before- because he’s generous. And because he’s so generous, he expects you to be generous back. And, you know, actors get scared and nervous and hold back, as we started to in rehearsal.

LIEBMAN: How did you rehearse?

HOPKINS: We went up to Napa where he has a big place- vineyards and everything. We read Bram Stoker’s novel together. That took two days- but it seeps down into the unconscious mind. We had about three weeks of rehearsal, with a lot of time spent improvising. He films a lot of the improvisations- everything is filmed.

LIEBMAN: Is that very unusual?

HOPKINS: I think it is. I hear he has moods of despair. Sometimes you have no idea what you’re doing, and when you’re working with him you sometimes sense that he doesn’t either. But you also sense that he’s in touch with some force of nature. He likes actors. At one point it seemed a lot of lines were being cut, and I got a bit upset, but he was right, I think. You can end up with more lines than you ever want. He leads you into all kinds of improvisation. When I went in the other day for the film test, he said, “Just go in and jump off the deep end. Let yourself be used.” He got me to do a twenty-five-minute improvisation. I was going to play Van Helsing as an old, crazy German professor or something, and he said, “Why don’t you play him romantic and sexy?” Yesterday we went through clothes and hairpieces. He wasn’t even there at first- I was early- and we did a test, and I suddenly had the sense that I was getting at something. I decided Van Helsing should have a dueling scar, a sexy look of history. I thought, This man has fought duels over women. He’s a genius. He’s drunk absinthe, smoked opium. He’s done everything! He looks dangerous, yet he’s a good man. I decided to do him with a light Dutch accent.

LIEBMAN: A light Dutch accent? Ah, yes. He is a Van, not a von.

HOPKINS: [laughs] Yes. A light Dutch accent, don’t you think?