let's talk about sex

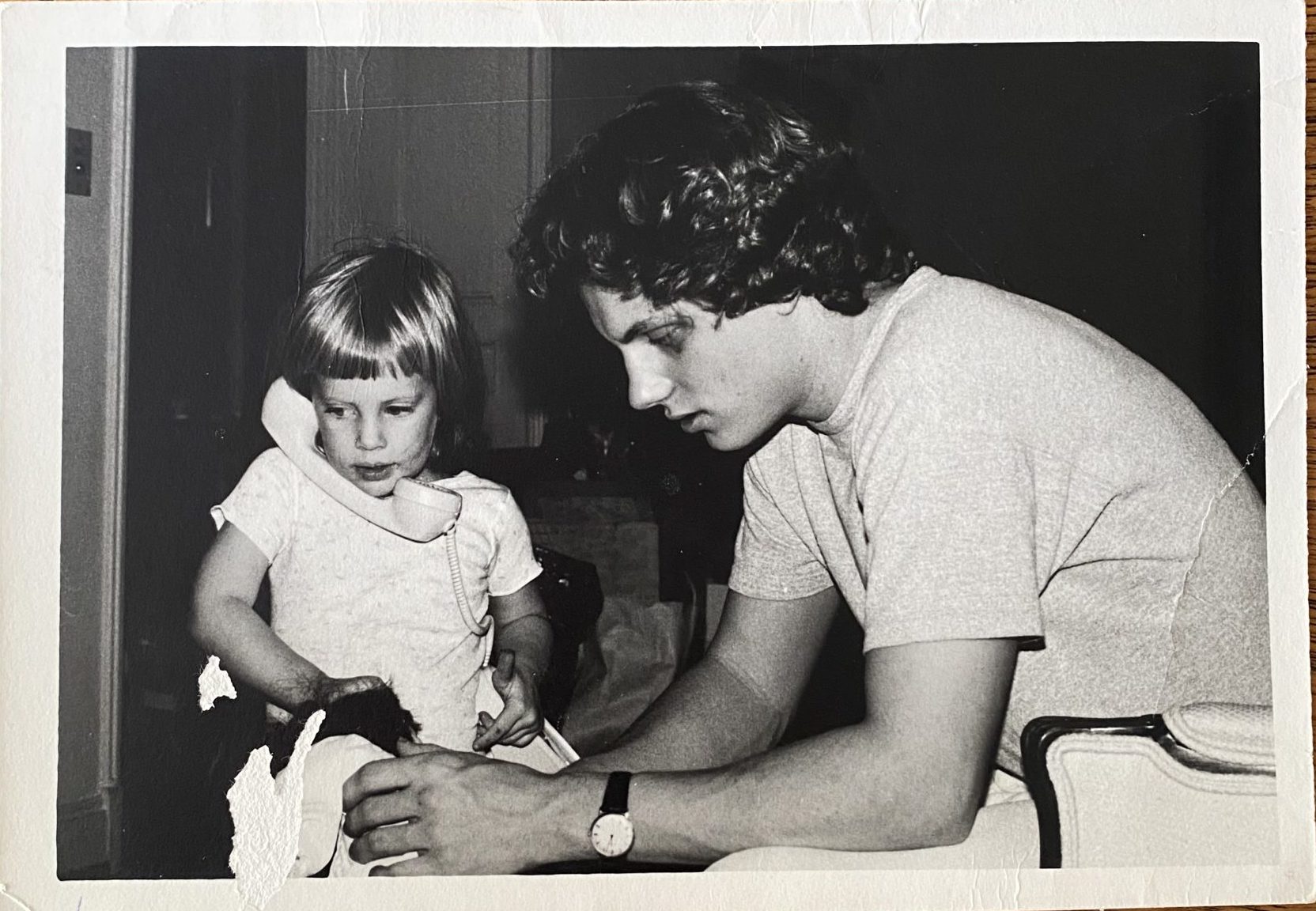

Liz Goldwyn Talks to Her Brother Tony About Sex

Liz Goldwyn, the Los Angeles-based writer, filmmaker, and artist-turned-sexuality guru, caught on to the importance of sex from an early age. She was stealing her father’s Playboy magazines when she was just a little girl, a feat her older brother, the actor Tony Goldwyn, never pulled off. It’s that curious nature that turned Goldwyn into a sort of Nancy Drew for sex, asking the questions people are often afraid to ask. She has built a career deconstructing the taboos built around sexuality, not only the extreme and kinky corners of sex, but also how it shapes our day-to-day lives. As a filmmaker, Goldwyn’s documentary Pretty Things, an adaptation of her own book, is an in-depth exploration of the golden age of burlesque. As an activist, her company The Sex Ed aims to fill America’s void of comprehensive, accessible sex education by providing a platform with “practical answers, real ‘sexperts,’ and humor.” In addition to the Sex Ed podcast, hosted by Goldwyn, her latest initiative is Sexpedia, a total glossary of sex, health, and wellness terms that includes everything from “Roe V. Wade” to “Cream Pie.” Once again, she has helped the country talk about sex in a way that’s accessible, informative, and fun. In that same spirit, Liz got on the phone with her brother Tony to talk about sex—and plan a trip to an X-rated toy store. —ERNESTO MACIAS

———

LIZ GOLDYWN: Hi, Tony! How’s it going?

TONY GOLDYWN: It’s going well! I’m interviewing my sister. How often do I get this? Not very often.

LIZ: It’s the first time, actually. Right?

TONY: I often feel like our conversations are not for public consumption.

LIZ: They’re not that bad. I feel like even things that maybe you were uncomfortable with when I was a teenager, now you’re more open about, too.

TONY: Don’t judge me.

LIZ: You’re one of my most woke family members.

TONY: First of all, so people know, I’m a lot older than you. I’m 16 years older than you. So, talking to one’s teenage younger sister about sex is a tricky subject for a young man. Not that it should be. I’ve ended up doing it pretty openly with my daughters, but you’re right. You were always sort of unflinching in your curiosity and in your outspokenness. That’s helped me evolve as a man.

LIZ: I know that there was a couple of times where I gave unsolicited advice to your daughters that you were concerned about at the time.

TONY: There was only one.

LIZ: When I said it was better to smoke cannabis than drink at a frat party.

TONY: They were like 10-years-old, and you were encouraging the use of marijuana, and I was like, “Maybe wait on that one.”

LIZ: I think that’s a little revisionist. I was explaining that college frat parties are a hotbed of drinks getting roofied and date rape. That’s why I was suggesting that when they got to that point, it would be better if they smoked a spliff. Because the worst thing that would really happen was they would get tired and want to go home and have the munchies.

TONY: I completely agree with you. It was all good, and they did survive college without incident. So I have you to thank for that, and they look to you for good advice. So let me ask you something, because this is an interview about you, so it got me thinking about the incredibly interesting career that you’ve had and how diverse it has been. I feel like when I look back on it, everything you’ve done seems to be building to or have a component of what your really intense focus is now, and that’s sex, health, and consciousness. When you were in high school, you were working for Planned Parenthood. When you started out working in fashion, you went to art school, studying photography, and then worked in the Sotheby’s fashion department and got deeply into vintage fashion and really became an expert in that. You also worked in the beauty industry for Shiseido, you worked in Japan, and really became a tastemaker in fashion. Then you made your first film, Pretty Things, a film about burlesque.

So, beauty and fashion and female sexuality and female power have always kind of woven their way through all of your work. Now, you really are focused almost exclusively on sex, health, and consciousness, which obviously is the birth of The Sex Ed. What was the commonality in all the incredibly varied things you’ve been doing in your career?

LIZ: I think a lot of it goes back to stealing dad’s Playboys when I was a kid.

TONY: I could never find them. You were more determined than I ever was.

LIZ: We have different moms, but my mom, as you know, was on the board of Planned Parenthood, a super feminist, very active in reproductive justice. So she has her view on sexuality, very political, and social justice focused. Dad was a lady’s man and a charmer, and read Playboy. He loved women. I was very conscious from an early age that sex somehow defined a lot of what my parents’ motivations were. From an early age, I was aware that all the adults around me seemed to be so driven by this mysterious thing that no one would really talk about openly. It was almost like I could see it as a color. There was a gray color or something around it—it was this thing that was so much a part of everyone’s psyche, but they were afraid to speak openly about it. I always felt like things were buried around me.

I would go through the library in our house that I grew up in, that our grandparents built, and go up to the really high shelf. I’d have to stand on the couch and then climb up into the bookshelf, and then I would steal his copy of Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Sex But Were Afraid to Ask. I got in trouble for that, actually. But that never went away. I feel like every single day, even yesterday, I learn a new fact about sexuality that totally blows my mind. I was probably in high school when I started becoming obsessed with sex work and I started telling you guys, “I’m going to build a brothel.” I think that the different avenues that I went in my career, or different mediums, were all just different ways of expressing the same through-line.

TONY: Art’s always been an important lens that way. I feel like you do approach it, in many ways, as an artist. The Painted Ladies thing you did is a piece of performance art in a real environment where you kind of toured through an early 20th-century brothel.

LIZ: It was an 1890s brothel and there was full-frontal nudity, although you weren’t allowed your phone and you weren’t allowed to touch or photograph the girls. I worked with a perfumer to scent all the rooms. I went to art school and the high school I went to on the East Coast had real arts focus, where you had almost like a major. Mine was photography. That’s when I started shooting nudes, not of myself, but of my friends. A group of students and I started the first rape and sexual assault group on campus. And prior to that, I was an AIDS teen peer educator. We didn’t have systems in place as we do now to talk about any of this stuff. There was no Google; you had to come in and check out a book or a pamphlet. Now, with my company The Sex Ed, it’s so cool that so many people write us from all over the world asking how they can get into this field, because it wasn’t a field that people wanted to be in at the time.

TONY: So much of your work is about locating the nexus of a woman’s power through open dialogue, shining a light bulb in hidden corners of things that people are often very uncomfortable talking about. One of the things that I found fascinating about that film, Painted Ladies, is there’s this sort of line that gets crossed between sexual power and exploitation by men. I would love to hear you tell me about the fascination with that line. I’ve been to modern-day burlesque shows with you, and the experience of burlesque for me is both arousing and beautiful. The female performer is a powerful figure. And yet in the history of it, it was driven by the service of men’s sexual appetite.

LIZ: I mean, the first thing I want to say is, how many people can say they’ve watched a strip tease with their sibling?

TONY: Good point. More than one!

LIZ: And in a very wholesome way. I think the thing is, it depends on who has the power in those sexual situations. Let’s be honest. We grew up in a movie business family, and when I was doing research for my first film, Pretty Things, I was like 17. I was very conscious that I was in a boys’ club situation in Hollywood. The system was not set up for me to excel past a certain point. So I think that played into my interest in power.

I was pretty young when I started working for corporations like Shiseido and Sotheby’s, and I was married at the time, too. I remember feeling like I had to play down my sexuality in order to be taken seriously. I was kind of always thinking about my sexuality—and my sex, my vagina—as something that worked against me in some way. I think I was looking for a bit of that to tap into for myself and figure out how I could utilize it to exist in the world in situations where I did not feel powerful. And I remember Zorita, one of my burlesque queen subjects, may she rest in peace, who was a huge influence on me. She was out, queer, and openly so in the 1930s, but obviously performing for mostly men. She really told me, “No matter how you slice it, wherever you go, men are going to be looking at you as a sex object. You better learn how to turn the table.” I was just always fascinated by that. How do we change this? How do I change this?

TONY: One of the things I think is so beautiful about the film Pretty Things is, as I told you before, it’s sort of like you’re Alice in Wonderland and these women were these figures of power. These incredibly powerful women who had power over men in one sense, and very much owned their sexuality, but at the end of the day, one felt that they didn’t have power and you were kind of picking up their mantle. In a sense, your mission has been to kind of restore their power. With The Sex Ed, your goal is to become like the Google of sex education. It feels to me like it’s about “People need to know about all of this.” Frankly, some people don’t even know that they have questions about it. Is that true?

LIZ: Well, people are uncomfortable talking about sex, death, and religion or spirituality. I believe that to have a healthy approach to sexuality, we need to be looking at it holistically and talking about wellness. And we also need to talk about consciousness. That does include religion and spirituality. Our background in those ideas form the way we think about our bodies, we think about our relationships, we think about sex—and that includes meditation and mindfulness. Like, if we’re talking about anal sex, for example, we want to approach it from a place of mindfulness. And if we’re talking about bondage or a kinkier fetish, we want to include meditation, breathwork, and mindfulness in that. Being on the receiving end of so many messages, DMs, whatever over so many years of my career, it all boils down to a lot of people walking around the world feeling like they’re alone, feeling like they’re not normal.

As much as I want to create that space for myself, I want to create that space for other people. I think it helps us evolve as human beings when we can learn from experiences that are different than our own. It wouldn’t work if it’s all my perspective, because my perspective is very different from someone who has a Muslim background, for example, or who’s grown up in another country or another city, or is transitioning. I’m trying to create a space where all these stories and experiences and people can be accepted. That does include, like you were saying on the podcast, conversations with people like yourself and Natasha Lyonne and Nick Kroll and Ramy Youssef, but it also includes conversations with people like Imani Gandy, who’s a reproductive justice lawyer, Ashlee Marie Preston, who’s a trans activist, or Asa Akira and Nina Hartley and Riley Reid, who are super famous porn stars. I think there’s space in the conversation for everyone because every single human being has an experience as a sexual human being.

TONY: You mentioned people who are in the, for lack of a better word, more extreme versions of sexuality, or more adventurous aspects of it. At the same time, you address very simple, basic things. People that may not be into bondage or fetishism or something don’t feel excluded from it. I think it’s important for people to know that it really is about that incredible spectrum.

LIZ: How do you know that you’re not into something unless you understand it? You brought up bondage. I remember very clearly when I was in my early twenties, Pretty Things had already come out. I went to the dentist and the dental technician asked if she could speak to me. She said that her sister had just passed. She was clearing out her sister’s apartment and she found underneath her bed this box with these purple fuzzy handcuffs, and it really freaked her out. She felt like she was judging her dead sister. And she just wanted to talk about it. Bondage can be a very useful tool for healing trauma and reclaiming boundaries and work through sexual assault. It can also be a really great way to learn trust and intimacy. I think we have to be working on our sexuality the same way that we would put time, energy, or even money into working on our workouts, or our education. We grew up in Hollywood, baby! How much time do people spend on preserving their youth?

TONY: I agree with you a hundred percent. If we want to evolve as people, or keep growing, whether it’s spiritually, career-wise, artistically, creatively, when you take that restriction off of sexuality and make it a holistic part of your evolution as a human being, it changes your life.

LIZ: I did not know who I was sexually, at all, when I was making Pretty Things. I was getting a crash course in sexual empowerment from strippers who were in their 80s and 90s at the time. In my personal life, I was married to someone I met at 18. I’m in a whole different ballgame now in terms of understanding my sexuality than when I was younger and first starting this work. I think an area which I think we need to shed more light on is aging and sex. We don’t have positives. We don’t really have senior sex modeled in pornography, for example. Just because you’re over 60 or over 70 doesn’t mean that you’re not sexual.

We need to see that kind of representation when we talk about inclusivity and representation, and that including diversity in terms of gender and sexual identity and race, that it needs to include age-appropriate age as well. That evolution, I think, is starting to happen more. We’re starting to see people be more accepting of it, but I think we have a long way to go. I don’t foresee a point in my lifetime, unfortunately, when we’re going to have comprehensive, standardized sex education in schools, at least across the U.S. This is why I feel like it’s my mission on the planet to do this work with The Sex Ed because I don’t want people to feel like they don’t have resources or they don’t have support.

TONY: Hopefully when we’re, let’s see, 80 and 96, we’re still having this conversation, and we can see where we’re at then. Hopefully, I’ll still be at it. I might need some assistance at that point, you know, some pills and whatever else they have by that time. But I intend to keep evolving.

LIZ: Yeah, just refill that Viagra. We’ve gone to the strip club, but we haven’t gone to the sex toy store, so maybe that’s the next frontier for us.