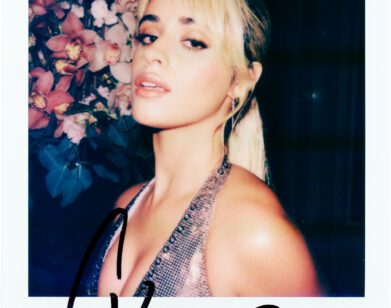

BOOK CLUB

Keke Palmer Tells RuPaul How She’s Surviving the Fame Game

When RuPaul read KeKe Palmer’s new memoir-cum-self-help-book Master of Me this summer, he knew it had to be the November selection for his book club. “This book is a life hack,” Ru exclaimed when the two got together earlier this month over Zoom. “This is a way for someone to navigate life in the 21st century.” Palmer, of course, has always been something of a wise sage, but the book gets especially candid about those moments when she didn’t feel all that confident or valued in an entertainment industry that’s notoriously cutthroat. “All of us have a version of us that we show the world,” Palmer explained. And for her, comedy and extroversion sometimes functioned as “defense mechanism in order to deal with some of my own sensitivity.” Along the way, she’s mastered a variety of self-care methods, from yoga and journaling to bible study and juice cleanses. As she told Ru: “All of them are welcome and all of them are at your well.”

———

RUPAUL: Oh my god. I’m here with author, actress, mother, and powerhouse Keke Palmer. Her new book is called Master of Me. I love this book.

KEKE PALMER: Thank you, Ru. I love you so, so much. You are absolutely everything.

RUPAUL: Well, you know, it’s interesting. I may know that, but sometimes a bitch needs to be reminded.

PALMER: Definitely that.

RUPAUL: It’s true. It’s important to surround yourself with people who can remind you who you are.

PALMER: I couldn’t agree more.

RUPAUL: I know that early in your career, you had your family around you. But who is around you now to remind you of who you are?

PALMER: Still my mom, my dad, my sisters, my brother, and then my really close girlfriend Leonora. I never knew if I was going to find a lot of people who would know me outside of the perception of who I am. I started performing so young. Once there’s this big idea out there about you, there’s almost this sense that the person you were before that disappears. I never felt that real genuine connection until that friendship, and then my son. Those relationships became new windows for me to see how I could really be seen.

RUPAUL: In the book, you talk about creating an extroverted “you” to perform on stage. But the real you is more introverted. How do you keep those in their proper lanes?

PALMER: Well, it’s taken a lot of years to balance it. Even outside of being a performer, all of us have a version of us that we show the world. It could be in reverse. You might seem more introverted outside, but then when you get home to the people that are close to you, they might see this super extroverted person. It can vary. But I think for me, I was always externally out, making jokes. It was kind of my defense mechanism in order to deal with some of my own sensitivity. But then when I’m in my own space, I’m very quiet. I love my alone time. I don’t want to talk. Even now when I’m with my son, there are no words. For me, it was realizing that I also deserved to exist like that. As an entertainer, that was the thing that people loved about me the most, but it’s just one aspect of who I am. It was many years of trial and error and figuring out that what I do is not who I am.

RUPAUL: Keke Palmer, who sings for the songbird?

PALMER: Now what does that mean?

RUPAUL: You know, you do all this performing, you give, give, give, give. Who gives back to you?

PALMER: Well, I don’t think there’s just one person. There are many things in my world that give back to me. My family gives back to me. God gives back to me through my experiences. My son gives back to me. I give back to myself. It’s a multitude of things in my life that make me feel like it’s worth continuing to be of service. And I do feel like that’s what makes life worth it. I talk a lot about loneliness in my book, feeling just a deep separation from life sometimes. We are always trying to figure out how to validate ourselves. So much of what we’re told is going to validate us doesn’t really validate us. Being in service to others, whether it be the type of movies I make or the type of books I write or the type of conversations I have—I feel a purpose in that.

RUPAUL: You know, when I go on vacation with my husband, I do everything. I make plans, I decide what we’re going to eat, what we’re going to wear. I’ve always fantasized about being in a situation where somebody could do that for me. But the truth is, no one can, or at least not to my satisfaction. So I’ve had to learn how to sing for myself, in a way. Obviously, I get value from other people, but sometimes it feels like an unfair exchange.

PALMER: I know what you mean by that, but I do feel like sometimes we are made to feel like it’s bad to sing for ourselves. For many years I struggled with that. I talk about that in the book, too. People would make me feel like my level of responsibility and my concern and love for others was something I was not doing autonomously. When in actuality, even as a young kid, it was a choice I was making. It was who I was and who I am. So I do wonder why we blame the people that sing for themselves. That’s what feels natural and true to them. So much of what I want to say is, “Hey, you’re the master of your own story.” If you believe in being of service, if you’re a leader, if you’re cool with singing your own song, there’s nothing wrong with that.

RUPAUL: You talk about that in the book, Master of Me. I found myself highlighting certain areas so I could go back and remember. I’m from San Diego, and when I was about 11 or 12, I used to catch the bus out to the beach. When I’d come back from the beach, the kids in the neighborhood would be looking at me all funny like, “Oh, you think you’re white or something? You think you’re better than us?” In the book you talk about that “tall poppy syndrome,” where people wanted to cut you down for following your dreams. How did you deal with that as a kid?

PALMER: Well, if I’m being straight up, I think I compartmentalized a lot of it. It was too much to process so young. I would journal a lot and I would get my feelings out. But I didn’t always externalize how it felt. I would say it to my mother sometimes but then I would shell up in certain scenarios. I think my refuge was my art. That’s where I process and express my story. But it wasn’t until my first book at 21, and now my second, that I’ve been able to actually put language to that experience. People ask, “How do you deal with being a Black woman? How do you deal with this or that?” Well, what other choice did I have? That was it for me. I felt that people were trying to write my own story. I felt misunderstood. I felt the burden of assimilation and holding onto my culture, but also blending them. I would go through these long periods of being uncertain and unsure, but I would talk about it. I would write it down in my journal. I would cry. I would seek therapy. I tried to be in service to myself in my darkest times. Eventually, I got to the other side. Instead of looking at something as a closed door, let me be objective and learn how this can be part of the story I’m writing for me.

RUPAUL: Can you share some of the practices you learned?

PALMER: I learned many different practices that I still use today. One thing was self-help and self-care. Like, actual retreats and routines that would allow me to have time and space to cleanse myself, whether that’s a particular juice cleanse or a spiritual awakening lesson on religion or philosophy. I’ve done therapy, working out, journaling. I do all the things I can do to help myself and cleanse myself on a mental, spiritual, and physical level. I think all three are equally important, anything I feel that can serve my individual growth. Maybe you don’t like yoga. Maybe you prefer working out, or maybe you prefer writing or hanging out with your friends and doing bible study. All of them are welcome and all of them are at your well. For me, I try all of them and I bounce in and out of any one of them whenever I feel like that’s what I need the most.

RUPAUL: Those life hacks are so important. You’re a new mother. Leo is your baby. Now I don’t have kids, but I often worry that I would create this great kid with knowledge and experience and then send this kid out into the world with all these dumb fucks. How do you reconcile the world that is and the child you are nurturing?

PALMER: It’s a bit worrisome. But then I think about my parents and my siblings. My mom would always tell me about the conversations that she had with my dad when she was really nervous about me. He would always say, “We raised her right and you have to trust that.” And that’s what I talk about in the book. I’m not asking people to believe in any particular thing, but you need to believe in something. You need to have some type of anchor. For me, it was growing up in the church, that sense of helping one another and knowing that good is going to come back to you. Forgiving myself, forgiving others, having no shame—all of that has helped me go through hard times in my life. That story about my mom is what gives me peace and the sense that I am going to give my son that anchor to protect him as he goes through life.

RUPAUL: Well, he’s got a great example in you because you are a hard worker. You are passionate. You are someone that people can learn a lot from, and it’s all in this book, Master of Me, which actually comes from a Shakespeare quote. “A jack of all trades is a master of none, but oftentimes better than a master of one.” What does that mean to you?

PALMER: Honey, it means everything. All my life I had heard that quote, and I always hated it even as a kid before I understood it in its totality. I just always felt like, “Well, why can’t you be a master of all things? Why can’t you do multiple things? Why does that mean you’re not that good?” So when I did the research for the book, I talked about a lot of the origins around that. The original phrasing was born during the industrial revolution where people wanted you to really prioritize one industry. “A jack of all trades, master of none.” Then over the course of time, it’s become, “A jack of all trades, master of none is oftentimes better than a master of one.” And I love that because what I always felt was, “Isn’t it amazing if you’ve mastered yourself so much that you can be diverse and able to get your hands into anything?” True mastery shouldn’t be placed on mastering an industry. It should be placed on mastering oneself—centering yourself as the industry, as the thing that you are providing for, not someone else. Because what happens if that industry decides they’re done with you? What happens if it implodes? How are you going to be able to pivot? We’re in such a crazy world where we have to balance our spirit, but we also have to balance living in a system like we’re in a matrix. And honey, we can’t just conk out and pull the plug out. We gotta figure out how to survive.

RUPAUL: Absolutely. You are speaking my language. And I’ve got to tell you that the thing I’ve admired the most about you all these years is that you have done so many things. Emmy Award-winning television host, actress, performer, singer, philosopher, mother. You are doing it all. But what’s one thing that you don’t do yet but have your eye on doing in the future?

PALMER: Oh, man. I feel that I’m moving into that pathway but there’s so much more that I have to learn. I would love to do more public service from a community standpoint. I think about different groups. A lot of people, when they think about the Black Panthers, they just think about all this, you know, “aggressive” stuff. But when I think about the Black Panthers, I think about the breakfast for the kids before school. I think about the healthcare clinics that they put in the communities. I think about all the ways that they created a system that would allow the community to survive at large. And since we’re in a time where we can’t always depend on our government to do that, those are the things I think about. That’s what I saw my dad do when he would go speak at prisons or make food at the old folks home. I mean, he just did so many different things, so I would love to be able to figure out how to continue to be of service in that kind of work.

RUPAUL: I love that. And I love you, Miss Keke Palmer. This book touched me in ways I wasn’t expecting. I mean, the depth of it and the life lessons are so valuable. This book is a life hack. This is a way for someone to navigate life in the 21st century and I am so proud of you.

PALMER: Ru, you are a mother to us all. It is such an honor to hear you saying that. I mean, I’ve grown up watching you do the very thing that I’ve always been attempting to do. Across the board, you’ve done so many different things and erased any limitations that people could put on anyone like us. To be here having this conversation with you, and for you to see that in me and to encourage me in this way, it means the world. You’re just so fabulous.

RUPAUL: Thank you for talking to us. Thank you for sharing your experiences with us in this book. I read something in there about Rosero McCoy. He was on my talk show on VH1 in 1996.

PALMER: Because he knows your choreographer [Jamal Sims].

RUPAUL: Yes, they were together for many, many years and they were both dancers on the show, so I’ve known Rosero for years and years and years. It’s so interesting what a small community this is.

PALMER: It’s crazy. The world is really so small. Everybody is connected in one way or another.

RUPAUL: That’s why I tell the kids on our show, “Be nice, show up on time, know what your lines are, pay your taxes, and make sure that you lead with kindness because don’t nobody want to work with somebody who’s got all this bad energy around them.”

PALMER: Don’t nobody want to come to work with nobody that’s all stank. It’s too much. We gotta be there all day.

RUPAUL: Thank you, Keke.

PALMER: Thank you so much. You are the best.

RUPAUL: Big kiss.