Jordan Castro’s The Novelist: Sincerity? Irony? Or Based Autofiction?

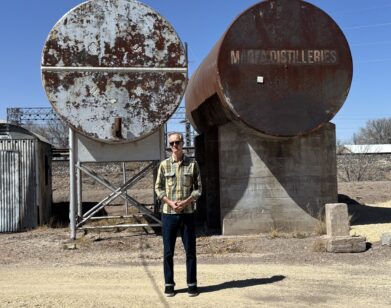

Photos courtesy of Walter Pearce.

“The Novelist: A Novel is Jordan Castro’s first novel.” That nine word opening sentence—self-aware, direct, and containing the word novel three times—feels like the appropriate introduction to a conversation about this auto-fictional book about autofiction. Castro, influenced by Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine and Thomas Bernhard’s Woodcutters, tells the story of a single morning of procrastination: a writer, battling the distractions of social media and his neurotic mind, avoids working on his debut novel. The entire plot, or lack thereof, unspools over the course of a few hours. It’s a clever conceit that Castro executes with disarming sincerity, exploring his narrator’s quotidian mundanities and interior life with reverence and precision. This kind of sincerity, especially when sustained in the face of absurdity, is a hallmark characteristic of alt-lit, an amorphous movement that Castro, the former editor of the influential alt-lit publication, NY Tyrant Magazine, is considered a member of. But where The Novelist most succeeds is in its use of tropes of the genre to transcend the genre, pushing its premise to some logical limit, stopping just short of the cliff over which the project might fall into a satirical abyss.

I wanted to ask Castro about how he struck this delicate balance and also discuss book promotion, literary memes, the internet, addiction, hope, and more. So, we spoke over G-Chat—seemed fitting—about a month before The Novelist: A Novel was slated to be published by Soft Skull Press.

———

GIDEON JACOBS: The first thing I would like to ask you about is interviews. The book is due out soon, and I imagine we’re talking today at the beginning of what’s going to be a pretty busy period of you promoting this book. Does that part of the process sound enjoyable to you? Or awful? Do you like talking about your work?

JORDAN CASTRO: I just typed something then my dog pawed the keyboard. I took some live action shots of him trying to nuzzle into the laptop. One sec.

JACOBS: Send!

CASTRO: Okay, back to the question: promoting and talking about the book has been fun so far. It’s a good excuse to be able to talk about ideas I’m interested in. Also, people have started posting Novelist memes on Instagram to promote the book, and that has brought me much joy. It kind of makes it all worth it…

JACOBS: About the memes—what do you make of them, especially their tone? They seem to be sincerely promoting the book but doing so in with a internet-y level of irony and irreverence.

CASTRO: I love the memes. They make me laugh. It seems like a good way to promote the book because it’s fun and self-aware, as opposed to the traditional model of being boring. I’ve wondered if they will make the book seem less “serious” or something, but I’m kind of just a sucker for shitposting.

JACOBS: I don’t think it makes the book seem less “serious.” It’s 2022—memes and shitposting are consequential and serious.

View this post on Instagram

CASTRO: Yeah, exactly. Also, traditional promotional means, like a review in The New York Times barely sell books, unless it’s like the review that “everyone’s talking about” or whatever. A publisher I was talking to the other day told me that an average review in The Times might sell like 30-40 books. I have no idea if that’s true, but I believe it.

JACOBS: That’s sad but sounds right to me. Or maybe it’s not sad at all and that’s just a dumb reflex, to call it sad. Maybe it’s great.

CASTRO: I think infusing the promotion process with mirth is necessary.

JACOBS: 30 books—makes me wonder what the fuck are we doing right now? If a highly coveted New York Times review barely moves the needle, what’s this online-only interview gonna do?

CASTRO: I’m not really sure. It’s for the culture, man! The culture…

JACOBS: Lol.

CASTRO: Hmm…trying to think of a better answer…

JACOBS: I think CULTURE is a fine answer.

CASTRO: It also might help sell some books. And that’s good.

JACOBS: While we’re on the topic of the internet—the book does a great job of capturing the compulsive nature of our internet habits. It spares no details in articulating the narrator’s digital behavior with a kind of excruciating exactness. Sometimes it borders on absurd, but I think that’s probably only because you committed to a high level of realism. Why did you want to spend so many words on the minutiae and mechanics of the protagonist’s navigation of the internet?

CASTRO: On one level, I wanted to capture “what it is actually like” to get distracted by the internet. But I also wanted the book to be about consciousness, the limits of “self-knowledge,” and so on. We think of ourselves as acting rationally, or thinking, then acting, in a kind of straight line, but in reality all kinds of weird contradictory stuff is going on. Using the internet can encapsulate that kind of perfectly. When I started working on the book, I wanted to try to observe what was going on, to stop in the middle of unintentional scrolling and be like, “Okay, what just happened.” And then, of course, the goal was to make it fun to read.

JACOBS: Your protagonist is procrastinating writing a novel about drugs and addiction, and while The Novelist isn’t overtly about drugs and addiction, at points it feels like the internet, which is often designed to addict us, is the drug of this book. Would you say that’s a fair characterization? Do you see the internet as an intrinsically bad force in the world of your book? Or in the world at large?

CASTRO: That might be a fair characterization. There is that bit in the novel about the narrator feeling self-conscious about describing stuff that isn’t drugs as being “like drugs,” and I feel a little bit of that now. Although I think that anything can sort of act as an addictive object, something we attach a kind of spiritual desire to, then come up against repeatedly, then keep doing despite what it’s doing to us. I’m not sure if the internet is a good or bad force in the world overall. My wife, Nicolette, thinks it’s bad, and Sam Kriss just wrote an essay about how the internet is made of demons. They’re probably right. But I think it might be too soon to tell. And I’ve been on it for so long that I don’t have a clear perspective on it. It’s been both good and bad for me.

JACOBS: It’s probably both good and bad, just like us. But there certainly seems to be some consensus forming that it’s a net negative.

CASTRO: For the last two years, I’ve stopped using social media during lent, and it’s felt really great. My plan is to get back off after I’m done promoting the novel. So I guess that is my revealed preference.

JACOBS: You’ve taken the genre of autofiction to an extreme with The Novelist, almost seeing how far you can go without something breaking. How much were you thinking about the literary context in which your book would be published, this moment in which autofiction is popular?

CASTRO: I sort of came up during the autofiction era, and when I was younger it had a lot of promise for me, but over time I began to feel disillusioned with it. There are passages in the book that I view as critiquing autofiction. I think I was less “aware of the context my book would be published in,” in terms of autofiction, and more just wrestling with my own relationship to the genre. When I was younger, I believed, “Anything can be art! All the old ways are stupid and I can just write about myself however I want and it’s just as good.” It was also weirdly tied up with this almost therapeutic mode, where somehow writing about oneself would make one’s life better or give them perspective. “Liveblog” by Megan Boyle—a masterpiece, shout out Megan—is like that. At the beginning she says that she’s going to try to document everything in hopes that it will help her change (I’m paraphrasing), but it isn’t clear that it actually helps. Also, like most people who use the term, I am still uncertain as to what it actually means. So, with The Novelist, I tried to infuse the genre with something from outside of it, a different orientation. The narrator is working on an auto-fictional novel, and so it’s, in some ways, about autofiction.

JACOBS: Underneath or parallel to all the discomfort of this book, the painfully obsessive and wandering attention of the protagonist, is his partner, Violet, and their dog, Dillon. To me, if there’s any solace to be had in The Novelist it seems to be that we possess just enough agency to love who we decide to love, and be good to them. Do you see the book as a hopeful project? Do you feel, um, hopeful?

CASTRO: I do. I can try to think of more to say. One sec.

JACOBS: We can also just end on “I do.” Up to you.

CASTRO: That could be good actually.

JACOBS: Or maybe we end it by including this discussion of how to end the interview in the interview.

CASTRO: That could be good.

JACOBS: I’ll try both.