memorial

Joel Meyerowitz Talks to Ryan McGinley About Shooting the Aftermath of 9/11

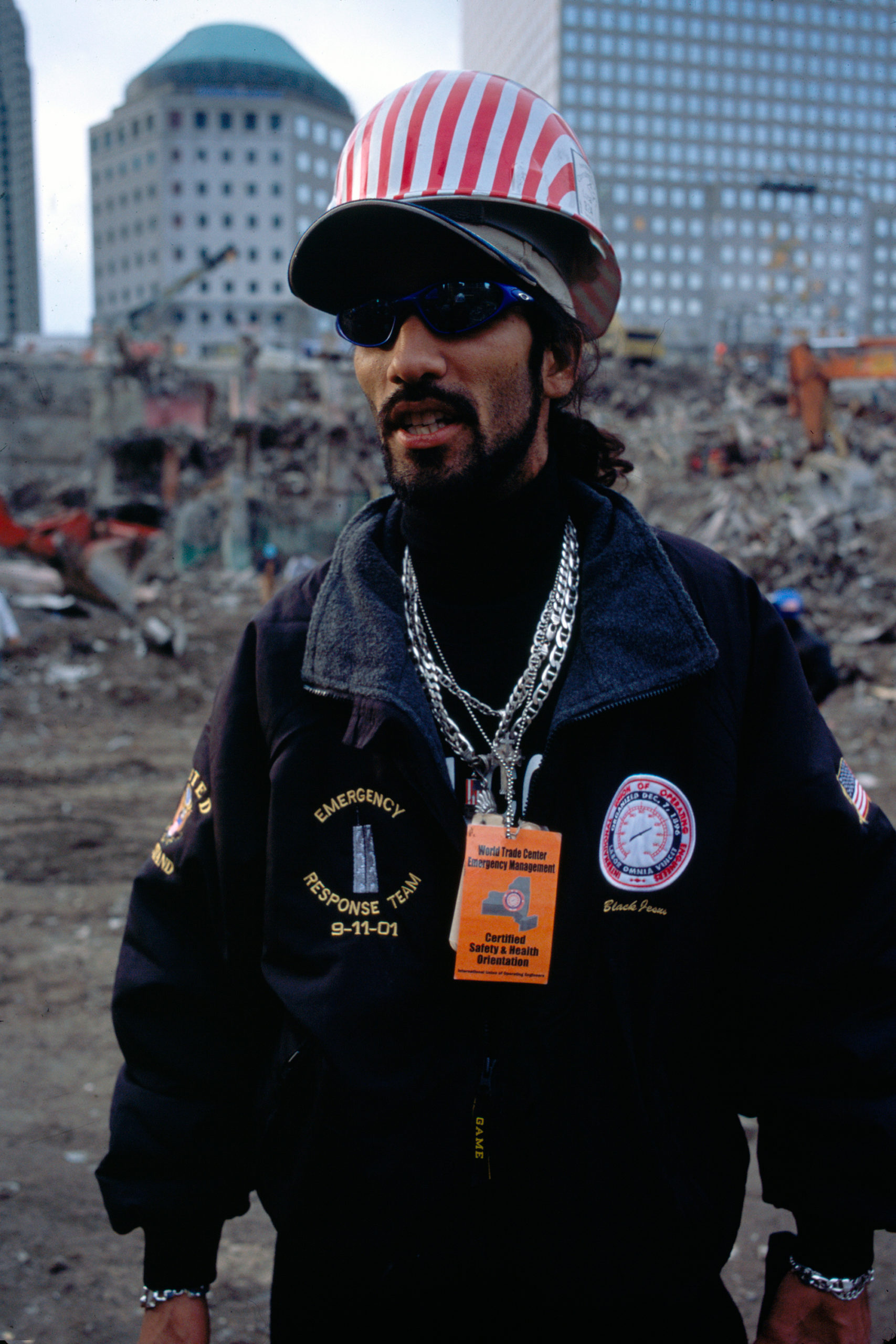

A safety inspector, 2001.

It has been two decades since 9/11, 20 years since two planes flew into the World Trade Center, killing thousands and changing New York City forever. One of the small blessings of that horrific tragedy is that the eminent street photographer Joel Meyerowitz, who over the course of his six-decade career has shot some of the most stunning portraits and cityscapes, took it upon himself to record the aftermath. For nine months, largely thanks to his own tenacity and understanding of history, Meyerowitz returned again and again to Ground Zero to document the site in all of its cruel collisions of steel, its fragile human moments, and the countless workers and volunteers who searched for survivors. We tend to think of visual artists as pioneers, revolutionaries, rebels, or romantics—and in Meyerowitz’s previous and subsequent work, he’s conjured all of these identities—but we rarely think of them as heroes.

———

JOEL MEYEROWITZ: Ryan, I’ve been following your work for a long time. I went to your show at the Whitney [Museum of Art] in 2003. How about that for history?

RYAN MCGINLEY: That makes me so happy to hear. That feels so long ago now, especially post-pandemic. It really makes it feel like a different era, a different me, with a different attitude towards photography.

MEYEROWITZ: That’s part of the joy of getting older as an artist. You begin to see who you were at different points and how you managed to get through that period, and become another version of yourself. For me it’s been a journey of 60 years.

MCGINLEY: Just thinking of six decades of your photography and the ways you’ve challenged yourself with a camera is so inspiring. One of the things I respect is that when something seems to be working for you, you’ll switch to the next thing. I think it’s part of an artist’s job to abandon the thing that you’re getting celebrated for and move onto the next challenge.

MEYEROWITZ: Yeah. The medium pretends to be one-dimensional—it’s just a camera with film or a chip, and it makes images. But we’re so complex, and the medium asks a lot of questions of us. I’m entering one of those phases now at 83 years old. I live in Italy and something has happened in the last five or six months. Some new questions have come up. I feel like I’ve been in a dialogue with two artists, Philip Guston and Giorgio Morandi, and they’re making me see if I can make photography do something that it’s not meant to do. I feel like I had a visual breakthrough just this past weekend. I’ve been trying to figure out a way to do something that’s rugged and rough and that challenges the illusion of three-dimensional space.

MCGINLEY: I just curated a show at David Zwirner of Mark Morrisroe’s photography. You might have run into him over the years because he was part of that Boston crew with Jack Pierson and Nan Goldin and Philip-Lorca diCorcia. He did some really dirty, gritty work that played with three-dimensional space.

MEYEROWITZ: I actually met Mark a couple of times on the Cape with some of the others you mentioned.

MCGINLEY: Yeah, you took those beautiful Provincetown photographs in the ’80s that include two friends of mine, Jack and Tabboo. They were just babies then.

MEYEROWITZ: They were babies, weren’t they?

MCGINLEY: That brings me to your 9/11 series. It’s the 20th anniversary. But I wondered, in your decades of shooting street photography before 9/11, if you shot around the World Trade Center much.

MEYEROWITZ: I did. When they were building the World Trade Center and they cleaned out the waterfront along the bottom of Manhattan, they made it into a big sandy beach. I photographed a lot in lower Manhattan while watching those buildings go up. Then, I’d been inside the building for various reasons over the years. There were meetings in ad agencies there, and one year, I hosted a 50th wedding anniversary for my parents at the top of it. I remember what the inside felt like.

MCGINLEY: Wow.

- A Salvation Army volunteer in front of the Taj Mahal, 2001.

- A worker carrying a hydraulic-hose connection, 2002.

MEYEROWITZ: Also, the streets around there used to be a big radio and hi-fi district. I would go down there to get a new turntable or to repair equipment, so it was part of the street life that I knew in New York. But I took those buildings for granted because they were there. And then, when they suddenly weren’t, I felt like I needed to do something. But there was nothing to do. Then, I was standing on a corner down there a couple of days after the event and I just raised my camera. There was nothing to see because they’d covered up the site with fencing and big tarpaulins. But when I raised my camera, a cop behind me punched me in my shoulder and said, “Hey buddy, no photographs here. The mayor says all photography is prohibited.” I said, “What are you talking about? We’re standing on the street.” And she said, “It doesn’t matter. No photography allowed.” Here I am face-to-face with this cop, and she said, “I could take that camera away.” I said, “No, you can’t. I’m a citizen. I pay my taxes. I pay your salary. I’m standing here on the street, and I can take pictures on the street if I want.” We had a stand-off. I said, “Well, what about the press?” And she said, “They’re not going in.” She pointed over her shoulder and up the street there was the press corps all tied up with yellow police tape. That’s when I had one of those lightbulb moments. I thought, “I have to get in, because how is the record of this disaster going to be made if no one’s allowed to take pictures?” I thought about that fucking fascist Giuliani. And I thought, I’ve got to work around this.

MCGINLEY: That’s the spirit of a New Yorker, right? In classic New York style, good things come to those who hustle.

MEYEROWITZ: Yeah. But it was just that flash. If she hadn’t stopped me, I wouldn’t have gotten that edgy feeling about doing something. I called some friends I knew in government and one of them was the commissioner of Manhattan’s parks. I’ve known him since he was a kid. I said, “Listen, can you get me in?” That evening he gave me a badge and said, “Go down there tomorrow morning and I’ll have one of my rangers meet you and take you in and then you’re on your own.” So that’s what I did. The guy got me in and dropped me in the middle of Ground Zero. The first thought I had was, this is dangerous. I need a hard hat. I’m looking around and I see a hard hat hanging on a nail. So I put it on and it fits perfectly. The hat says NYPD on the front and on the back it has a big American flag and I’m thinking, “Oh good, my disguise is beginning now.” Then I got gloves and a pair of boots and a vest, and within half an hour, I was outfitted. I looked like everybody else except I was carrying a four-by-five camera, which I wasn’t exactly hiding.

MCGINLEY: You weren’t the invisible Joel Meyerowitz working unnoticed.

MEYEROWITZ: No, because it wasn’t right to do it that way. I needed to be identifiable as someone doing history work.

MCGINLEY: I love that moment where the cop nudges you. I think photographers need to have very thick skin. And even then, most photographers might have shrugged their shoulders and walked away. But a big motivator for me has been moments like that, where despite someone saying no, my thinking is, I’m going to do this. Rebellious photographer—those two words go together for a reason.

MEYEROWITZ: All of us who have a New York street sensibility know that you have to work around resistance, because you’re going to meet it all the time. So however you charm it, whether you’re tough or cute or sweet or fast, you find some way of being quick on your feet so that you can get what you want, in a way that doesn’t offend somebody. So when I got that worker’s pass, the first thing I realized was that they’d printed it on construction paper, the kind you get in any stationery store for school supplies. So I thought, if the city of New York is printing passes on construction paper then it’s not going to be very good quality. So I scanned that pass and just changed the dates, and I had all the colors for every time they changed it for that particular day. It worked, but I still had problems. All the cops down there were like soldiers. “I’m just following orders.” And I would say, “I’m the history guy.” They’d still say, “Get out.” So I would go around to another entrance and go in. Then, within a couple days, I met 12 detectives who were part of the bomb squad, and these guys got what I was trying to do. They said, “Fuck the mayor. We need this stuff for our kids and our grandchildren. We’re going to protect you, Joel.” These guys became my squad, and I had all their phone numbers, so anytime someone threw me out, I would say, “No, wait a second. I’m going to call my lieutenant.” I would hand the phone to the cop and the lieutenant would start screaming at them. It was like a cartoon. You could almost see all the asterisks and exclamation marks flying out of the phone. So, for 50 days, they protected me and then they had to leave. On the day they were leaving, I said, “What am I going to do? If I don’t have you, I can’t continue this.” And they said, “We’ve got this worked out.” They took me into police headquarters and had me photographed, fingerprinted, and barcoded, and they got a legitimate NYPD badge for me. It was the real thing. So when I showed that at the site, they said, “Right this way sir.” And that’s how I was able to stay in for the full nine months.

- A Salvation Army Volunteer in the Taj Mahal, 2002.

- Willie Quinlan, an ironworker, on top of the last column, 2002.

MCGINLEY: How often were you going down there?

MEYEROWITZ: At the beginning I tried to go every day because they were moving everything so fast. I had originally petitioned Giuliani to allow a group of six photographers, a video photographer, and an oral historian.

MCGINLEY: Wasn’t one of the photographers you had tried to bring in Mary Ellen Mark? I thought that was genius.

MEYEROWITZ: Absolutely. And if I had known you then, you might’ve been one of the people because your approach is so personal. I thought we would be like a miniature FSA [Farm Security Administration photographers of the 1930s and ’40s], but the mayor wouldn’t hear of it. So I felt I had to do all of this recording myself. I was working 14-hour days. I lived within walking distance so I could walk home at two in the morning, dump my clothes in the washing machine, take a shower, go to bed, and then be up at seven in the morning and go back again. I did that for a few months. It was taking a toll on me. Also, a publisher had given me a $20,000 advance to do a book on Tuscany and he called me up in November and said, “How’s the book going?” I said, “I spent the money on Ground Zero.” He wasn’t so happy about that. So at the beginning of January, I went away for a few weeks because things down there had stabilized. When I came back, I was going three or four days a week, except in the last ten days, I went every day. It was the time of goodbyes. I had come to know hundreds of people down there: principals, engineers, and construction guys who were running the show, as well as cops, firefighters, nurses, and therapists. It was a big community and I felt so much a part of it.IgrewupintheBronxinareal working-class neighborhood. And here I was back in the pile with guys just like the guys I grew up with.

MCGINLEY: I would imagine that they reminded you of your father.

MEYEROWITZ: They did. And of my whole neighborhood. Because I’d had an education and moved in different circles, that part of me had been paved over. But when I was down there with them, it all came out again, the basic decency of everybody and the street-smart, no-bullshit, say-it-like-you-feel-it way. It woke something in me that was a primitive memory and I truly loved that experience, because I’d drifted away from all that.

MCGINLEY: Aftermath, the book you made about your time down there, has that special quality of photojournalism you bring to a project, as well as your Cape Cod light. A lot of it was obviously shot in the fall light, and the light changes so much in New York City over those months in autumn. The series also made me think of the portraits of August Sander and the cityscapes of Berenice Abbott. And it reminded me of paintings of Pompeii, the Acropolis, and the Coliseum.

MEYEROWITZ: I think you’re in touch with a lot of the variables in play. To find myself inside this catastrophe with two gigantic buildings that fell, the chaos of it, the landscape of it, was like nothing we’ve ever seen. It was more vast and monumental than any of the great ruins of history. The hardest part was dealing with the beauty, because we tend to think of the disaster as a tragedy. After being in there for a number of weeks, I began to sense that the tragedy was over when it happened, and the aftermath is everything that it looks like now. And when the sun shines on it, or snow falls, it’s nature erasing the memory as time itself will. And I began to feel like I had to accept this fact.

MCGINLEY: I imagine you were working through a lot of raw grief. How did you navigate your emotions down there?

MEYEROWITZ: There were a lot of people to talk to down there when I came across things that were really hard to bear. The little rituals and processionals were so moving. I would sometimes find myself watching something with tears rolling down my face, and look at the guy standing next to me, some cop or construction worker or fireman, and he’s bawling, too. And the two of us would hug or put our arms around each other’s shoulders because we recognized at that moment that we were witnesses to the reality of that place. When they found the remains of somebody, my feelings were present on the surface. It was hard to become tough-minded about it. I remember one thing that was a real turning point for me. Every day, whenever they found a body, if it was a civilian, they would put the person in what they call the Stokes basket. It’s a little yellow plastic sled, and they cover it up with a tarp and bring it out. If they found a fireman or a cop, they would make a procession with a flag over it. One day, one of the licensed drivers was working her grappler and she came across the body of a woman from one of the towers, and she called one of the guys and he came over, and he started to call for a basket. She lowered her grappler over the woman and she got out of her cabin and said, “No, she gets a flag, too.” And the guy said, “No, we don’t do that.” And she said, “I’m not lifting this until she gets a flag and an honor guard.” There was a big confrontation, and some of the head guys came down and she refused to let them take the body. She said, “I’ve had enough of seeing the difference between civilians and the cops and uniformed officers. Now it’s time for everybody to be treated this way.” I had such chills. My legs were shaking. I became friends with that woman because she was such a heroic person. There’s a picture of her in the book.

Marty Siegel, Bovis manager, holding a roll of visitors’ passes to the World Trade Center, 2002.

MCGINLEY: Were there any constraints or requirements that you put on yourself? Was there anything off-limits to shoot?

MEYEROWITZ: I chose not to photograph human remains. There was a huge forensics lab on site, and every bit they found, whether it was a tooth or a bone or a body part, they took it in there and would try to find the DNA that would help identify everybody. I figured they have their forensic library of thousands of pictures of body parts all labeled with where they were found. I didn’t need to do that, and I didn’t want to be seen as a vulture scavenging that subject matter. So I stayed in the realm of all the other activity: men on their hands and knees scraping through debris, all the truckers and drivers and workers. I felt that as a historian. I wanted to see it down to the bedrock. I felt I should try to be as aware as possible of all the layers that it took to clean up the site. To me, that was a worthy task.

MCGINLEY: I know a lot of people developed health problems from being down there. Was there anything like that for you after working there for nine months?

MEYEROWITZ: Yeah, I’m in the program at Mount Sinai. And even though I wore a respirator and a hard hat, after nine months I started to have a respiratory thing. There’s no doubt that my breathing is compromised. There are guys far worse. Most of those 12 guys in the bomb squad have had serious problems. Some have died already. So I’m fortunate in comparison to them, but I’ve paid a price for it.

MCGINLEY: In terms of the city itself, even beyond 9/11, do you think that era of Manhattan is gone? Do you like the changes to the city in the past 20 years?

MEYEROWITZ: I don’t like those pencil-thin skyscrapers. There’s a bad visual vibe I get from them. And I don’t like the way the smartphone has compromised the way streets feel.IfIwasborninthisera, I wouldn’t know any better. I lived in an innocent era when people walked the streets wearing fedoras and overcoats and women still wore hats and gloves on the street. It’s crazy that I saw that. So although I love the energy in New York, I can also see the differences, and my memory tells me that it doesn’t feel so great right now. There’s a lot more pressure. Urban life has become more pressured in general. It used to be slower. As fast as New York always was, it was slower. Of course I haven’t been there since the lockdown and I’ve heard the city has started to come back with energy. I really admire you for having been out shooting all these months. That’s going to be a big body of work for you.

MCGINLEY: I’ve been out participating in the protests. I’m just there to amplify their cause. I linked up with the women that organized the Black Trans Lives Matter group and I’ve been creating those images, to have a historical record. I haven’t thought too much ahead, but I imagine it relates to what you were doing on 9/11, in the way that these images take on different meanings over time.

MEYEROWITZ: I have to say, when I first saw your work, I didn’t get it. And then I went and had another look and I thought, oh my god, he is so joyous. He’s just out there living the fullness of his life with his friends and his adventures and it’s about abundant optimism and playfulness, and I thought that was just right for the new century. And as I’ve watched you develop over the years, I found that thread in your work is your core energy, your offering to the history of our time. And so now, hearing that you’ve been out there, it’s really important what you’ve done.

MCGINLEY: Thank you. It’s been amazing to bring it back to New York after doing trips across America for over a decade. I started off shooting in the city and photographing my circle of friends, and now, to have another moment 20 years later photographing a new generation of New Yorkers that have something to say, has been really beautiful. I saw during this pandemic that you’ve been doing a series of self-portraits.

MEYEROWITZ: I’ve never really turned the camera on myself. So it was fun to see what I could come up with. Here I am, stuck in the middle of Tuscany, with not a lot going on. There are 200 sheep about 150 yards from where I live and that’s the action. So doing this series on myself was a provocation. But I’m pleased that I’ve kept a wacky sense of play throughout these self-portraits and that I didn’t take myself seriously and try to look good, because it’s not going to work when you’re over 80. You’ll look like you look. You have to deal with age and your ego.

An ironworker, 2002.

MCGINLEY: I’m just in awe of how you keep evolving the art form.

MEYEROWITZ: I think integrating ourselves with our art is a life’s work. In order to get close to the mystery of photography, we have to be susceptible in a way that we understand the magic and chanciness of it and the unexpected moment of it. That’s what photography is. And it keeps on reminding me that I have to live like that in order to stay within the spirit of the medium. We all develop our own methodology, our inner sense of intuition, and our values. It’s as simple as that, and that’s how you become a whole person. And maybe it’s better to be a whole person than an artist, because a whole person is an artist as well as having a fuller range of feelings. They’re not just dealing with art-making, but with living and making art out of your life. That’s what it’s been for me. I want to experience the freshness of seeing the world however it presents itself to whatever consciousness I have. Can I rise up to that again? That’s when it gets exciting for me.

———

Photographs © Joel Meyerowitz, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

Special Thanks to the Parks Commissioner.