Joe Berlinger Infiltrates the System

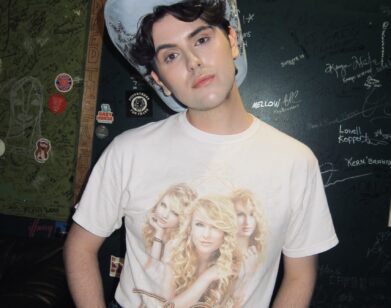

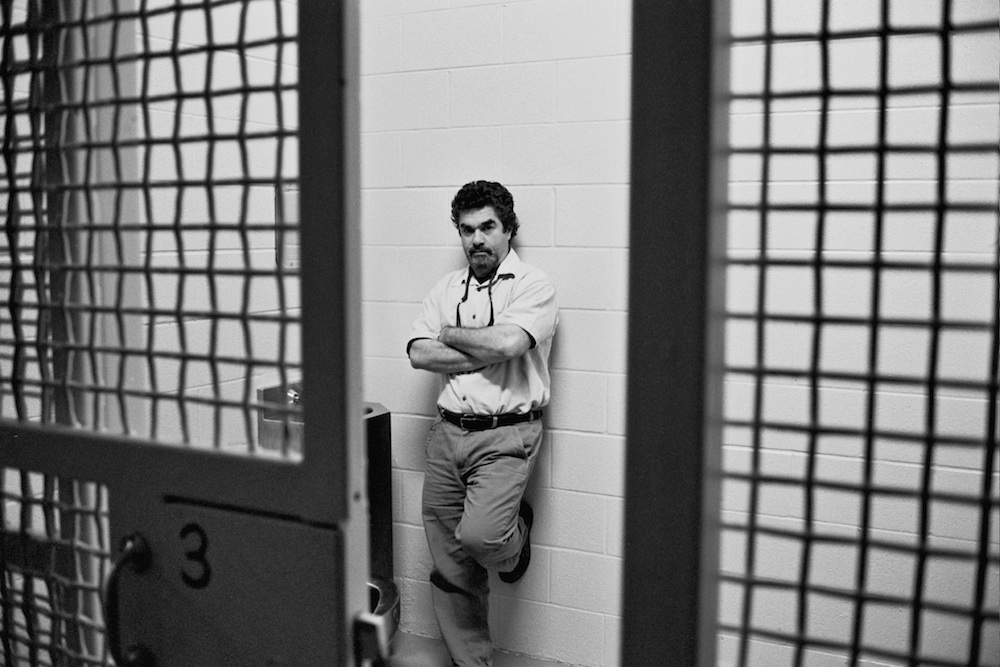

ABOVE: JOE BERLINGER IN THE SYSTEM WITH JOE BERLINGER

With his new television series, The System with Joe Berlinger, Joe Berlinger investigates the miscarriage of justice in the United States. Each episode focuses on a different problem, beginning with false confessions, mandatory sentencing, and the misuse of forensics. Berlinger humanizes these issues with specific case studies: throughout the show you meet alleged perpetrators and the families of their victims; people who believe they are innocent and people who believe they are not. Berlinger’s aim for the show is to educate: “I want people to become more familiar with the criminal justice system and the problems within the system,” he explains. “Perhaps the most core American value is personal liberty, and the criminal justice system has the ability to take that away from you.”

Berlinger’s entry into activism begins with a very famous case, that of the West Memphis Three. In 1993, HBO approached Berlinger and his filmmaking partner Bruce Sinofsky with a potential film idea: three teenagers had been accused of atrociously murdering three eight-year-olds in West Memphis, Arkansas. The duo traveled down to Arkansas to begin work on what would become Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (1996).

“What initially attracted us to the story was to explore how teenagers could do such a horrible thing: worship to the devil and ritually murder three eight-year-old boys,” the filmmaker and producer recalls. “We assumed that they were guilty because that’s what everyone was saying, that’s what the press was reporting, and we were spending most of our time with the victims’ family members.” After three months, Berlinger and Sinofsky were finally granted access to the three defendants: Damien Echols, Jessie Misskelley, Jr., and Jason Baldwin. It was not the open-and-shut case they’d signed on for. “It seemed to us that the wrong people had been arrested,” says Berlinger. “But we were still six months away from the trial, and I assumed that everything would work itself out at the trial” he continues. It didn’t. Echols was sentenced to death; Misskelley and Baldwin to life in prison. Berlinger and Sinofsky made two more films on the subject and, 18 years later, the three men were released, though not deemed “innocent.”

As Berlinger notes, “The West Memphis Three’s case is not unique.” For him, The System with Joe Berlinger, which premiered this weekend on Al Jazeera America, “is kind of the culmination” of what he began with Paradise Lost.

EMMA BROWN: When did you first start questioning the American justice system? Did you discover the flaws in the system through making Paradise Lost, or were you already aware of them?

JOE BERLINGER: No. The first Paradise Lost film was my wake-up call to the problems and inequities in the justice system. Ironically, when we first went down, we went to make the film about guilty teenagers, because that’s what we thought we were dealing with. Sitting through two three-week trials that were based on rumour, innuendo, and no physical evidence connecting the defendants to the crime scene, and where musical tastes were being used to indict them—it was just a wake-up call to how perverted the justice system can be. Going into those trials I thought, “My god, there’s such flimsy evidence here; there’s no way these guys are going to be convicted.” To see these guys become convicted and sent away, one to the death chamber… Bruce Sinofsky and I made it our mission to continue shining a light on that case for as long as it took. No one thought it would take almost two decades. That is where my sense of justice, and my sense of wanting to make people aware that these things can happen, was born.

BROWN: Do you feel like the flaws in the justice system have gotten worse over the last 20 years?

BERLINGER: I do. I think there are systemic problems. Certainly our system of justice often works fine, so I don’t want to just say, “Hey, the system is broken—nothing works,” because that’s an oversimplification. But there are a number of trends that trouble me. First is the number of prisoners we have in this country; we have five percent of the world’s population and yet we have 25 percent of the prison population—about 2.2 million people overall, which is a 13 percent increase between 2000 and 2012. I don’t believe that there’s more crime and that we have more bad people that need to be put away, I think there’s a problem with a system that puts that many people away in prison. There are all sorts of issues: the move towards privatization of prisons has deemphasized rehabilitation. The corporate prison-industrial complex is at work here—it’s more profitable to keep people in prison than to let them out. The thing that I’m concerned the most about is the extreme socio-economic and racial disparity: 30 percent of prisoners in 2011 were African American, and 21 percent were Hispanic. When you compare that to the general population, those are alarming numbers. One in 13 African-American men is in prison, compared to one in 90 white men. That’s a problem. This show tries to focus not just on wrongful convictions, which is the worse thing that can happen in the criminal justice system, but just extreme inequalities within the system that I think need to be addressed.

BROWN: Obviously not everyone you meet is going to have been wrongfully convicted. Have you ever had trouble forgiving someone for their crime? Or are you able to completely separate a person from their past actions?

BERLINGER: I try not to judge people. I’ve dealt with guilty people who have served their time and want a break in life, and I try not to judge them. If I’ve met somebody under circumstances where they’re still incarcerated and they don’t seem to be remorseful, I’m less sympathetic, but I try to treat everyone like a human being. I think the system needs to encourage giving people a second chance. The flip side to that is some people are given a second chance and do terrible things; [for example] the Cheshire Murders [in 2007]—those parolees went and committed a horrendous home invasion and a horrendous crime. That certainly gives one pause, but I think the system needs to become a little more humane than it currently is.

BROWN: The motto of the justice system is supposed to be “innocent until proven guilty,” but today it seems to be the other way around.

BERLINGER: The justice system is based on a set of ideals, as is the promise of what America should be, and I think we should always be striving towards that. I don’t want to say categorically it’s “guilty until you’re proven innocent” today because, in many cases, the system works, but you have a clogged system for a lot of reasons. For example, 97 percent of indictments end up in plea deals, as opposed to actually going to trial. That encourages abuse because people tend to take plea deals because they cannot afford to or are unwilling to go through a legal process. We did an episode, for example, on policing strategies: there are these “drug-free” school zones that end up creating urban areas where the entire area is a drug-free zone. On the surface, that sounds good—there’s an enhanced penalty for possessing drugs in a drug-free school zone. But, if you’re stopped and frisked, which is another policing strategy, and you’re caught with a small amount of marijuana and you’re in a drug-free school zone, there’s an enhanced penalty. So you have a prison system full of people who have been, because of their socio-economic status, stopped and frisked and they’re in possession of a small amount of marijuana. That case often never goes to trial because of the enhanced penalty—people don’t want to risk that kind of jail time, so they plead out to the lesser change, even though they feel they’ve been violated and that they’re not actually guilty. That puts them into a system that then encourages recidivism, because they then have a criminal record that makes it hard to get work. So there are all sorts of systemic problems that need to be addressed that are disproportionately weighing against the disenfranchised and minorities.

BROWN: What’s something you learned through the series that you weren’t aware of before?

BERLINGER: There’s no shortage of people who are claiming to be innocent, and it’s really troubling the discretion that prosecutors have. There’s prosecutorial immunity and it always shocks me, despite having done the Paradise Lost case, the degree to which some people believe that the ends justify the means. Because of DNA technology, I think the general population is becoming more and more conditioned to the idea that, yes, there is misconduct or ineptitude that results in wrongful conviction. Before DNA technology became so advanced, I think the general population had a much harder time understanding how people could falsely confess or how the police could make a mistake, or worse, do something to make sure somebody gets convicted, even though they shouldn’t be. But many cases don’t involve DNA. The other thing I think I’ve learned by doing the series is sometimes there are no easy answers. For example, we did an episode about mandatory minimum sentencing. We profiled one case in Florida where a guy named Orville Lee Wollard is serving a 20-year prison sentence. He was a man with no criminal record—a family man in his 50s—and his teenage daughter was being taken out of the house repeatedly by a boyfriend. He decided that this activity had to stop because they were doing drugs, so he told the boyfriend to leave the house and to leave his daughter behind. Instead of leaving the house, the boyfriend started coming at him. So he took out a gun—a legally owned firearm in his home—and he fired a warning shot into the wall. Florida has a “10-20-life” mandatory minimum sentence policy, which means 10 years if you take out a gun, 20 years if you fire a gun, and life if you hurt somebody with a gun.

BROWN: What about “Stand Your Ground”?

BERLINGER: The jury determined that this was not a Stand Your Ground situation. So this guy, because of 10-20-life, is sitting in prison for 20 years. That case made me sympathetic towards how mandatory minimum sentencing is very flawed and we should be looking at each individual case. That’s how I was feeling when I was in Florida. Then I went to Chicago for the second half of the episode, where we profiled a case of a young African-American girl named Hadiya Pendleton who was this beautiful, accomplished, straight-A student who everyone thought was going to go very far because of her intelligence and magnetic personality. One day, a gang member rolled up on a group of kids, including Hadiya Pendleton. In a case of mistaken identity, Hadiya was shot and killed by this gang member who was out on probation for a prior gun violation. Had there been mandatory minimum sentencing in Chicago, he would have been in prison and wouldn’t have killed this promising young woman. So her parents are vociferously fighting for mandatory minimum gun laws in Chicago. The show is not just about what’s wrong, it’s also examining the complexities of certain issues. I guess what I learned is that there are two sides to a lot of these stories.

BROWN: Do you ever get frustrated? It took a long time for the West Memphis Three to be released, and they still haven’t been declared innocent. Did you ever feel like, “This is pointless”?

BERLINGER: Never pointless, because you have to speak up and speak out, but “frustrated” would be an understatement. The thing that kills me about that case in particular is: I don’t think that they knowingly picked out the wrong people and knowingly put them in prison—I just don’t believe that was at play. In part because in order for us to film, everyone had to give us permission: the prosecutors, the judges, the victims’ families, and the defense attorneys. I think that if the prosecution, the judge, and the police were conspiring to put the wrong people in prison, they never would have given us permission to film. For me, it was a combination of prejudice and ineptitude and, while I don’t condone that, I’m not as troubled by that as what I perceive happened next. During the appeals process, when a lot of troubling questions about the convictions started being raised, it was at that point that I feel the wheels of justice inexcusably slowed down to the point of absurdity and unfairnes because people don’t want to admit mistakes. That’s where I have quite negative feelings toward the people responsible. Once you start keeping people in prison because you’re afraid to delve into the truth—that I find inexcusable.

THE SYSTEM WITH JOE BERLINGER AIRS SUNDAYS ON AL JAZEERA AMERICA.