Jamie Bell’s History Lesson

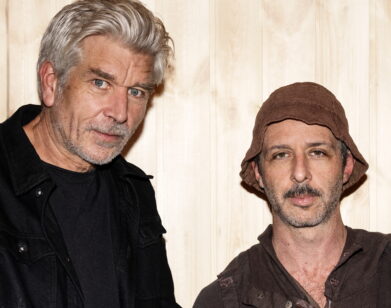

ABOVE: JAMIE BELL AS ABRAHAM WOODHULL IN TURN. PHOTO COURTESY OF ANTONY PLATT/AMC.

Chatty and cheerful, British actor Jamie Bell is aware of his good fortune. He’s recently been cast in the new reboot of The Fantastic Four, and appears in Lars Von Trier’s oh-so-shocking Nymphomaniac: Vol. II. But most of all, Bell has landed the 21st century’s highest entertainment accolade: a leading role in a one-hour cable drama, Turn, which debuted over the weekend.

Based on Alexander Rose’s book about the Culper spy ring during the American War of Independence, Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring, Turn has a high production value, the backing of a respected network (AMC), and a cast of fine actors such as JJ Feild and Angus MacFayden for Bell to work alongside. Bell plays Abe Woodhull, a Long Island farmer and son of the local magistrate who reluctantly becomes a spy for George Washington and his army of rebels.

The show marks Bell’s first regular role in a series since he began his career at the age of 14 with Billy Elliott, but television has changed a great deal since then. “People are genuinely invested in television,” he tells us over the phone. “To be the lead on a cable show is a lot of pressure, and a very sought-after thing right now.”

EMMA BROWN: You’ve mentioned before that television had a stigma when you first started acting, and that has now changed.

JAMIE BELL: I hate to use the water-cooler metaphor, because it’s not particularly British, but let’s use it for now: when people are standing around the water cooler, and they’re talking more about what happened on Breaking Bad, what happened on Sopranos or Game of Thrones, than they are talking about what happened in movies, something has changed. When I see people talking about TV, they’re way more animated, way more passionate than when they talk about films. That’s just fact. The reaction that you get out of someone from saying “I don’t watch Breaking Bad,” it’s like they want to kill you—you should be killed for not watching Breaking Bad. But if I say, “I haven’t seen Gravity,” they’re like, “Yeah, why should you?” I can’t decide whether it’s the way it’s delivered to people, or it’s the way that people are consuming it now, or just that the quality is better. I don’t know what happened, I just know for a fact that the landscape is different in the way people perceive it and the way people enjoy it. It’s a big business, and I’ve kind of been sucked into it.

BROWN: Is there a television show you watch that would cause such a reaction from you—”How can you not have seen this? You should be killed!”

BELL: I haven’t seen Breaking Bad. That’s why I know that; that’s the reaction I get with people. I also haven’t seen Game of Thrones—that reaction is insane.

BROWN: When people are indignant about your television ignorance, does it make you more inclined to want to watch the show, or do you become ornery and decide to hold out just because?

BELL: Sometimes it’s both—you feel like an idiot, and then it’s like, “Shut the fuck up, please.” But I like to find things by myself, and when I do, I’ll run through them in a weekend or something. Netflix has broken the mold; it’s completely destroyed the idea of weekly, episodic television. What a crazy thing. We’re entering a new phase of this, and it’s exciting.

BROWN: Do you think that cliffhangers are still important?

BELL: Yes, absolutely. I have fucked it up for people. Kate Mara is a friend of mine, and I was working on our show, and at that point I hadn’t watched House of Cards. Someone was saying, “I love House of Cards,” and I kind of guessed some information about what happened in the next season. I hadn’t seen it, so I wasn’t invested, and I completely ruined a surprise for this person. They were so upset, they wouldn’t talk to me for two days. So the measure of investment is enormous.

BROWN: I grew up in London, and I feel like we never learned about the American Revolution in school or anything like that…

BELL: Thank you for saying that. I thought, “Is this just like some weird amnesia thing? Because I literally don’t remember seeing anything in a textbook, or being told anything about it.” When I got the script, it was like, “What were we talking about? I don’t understand.” I think as English people, we don’t want to be reminded that at one point we ruled three-quarters of the globe, and now we’re a very small country that doesn’t own three-quarters of the globe.

When I started coming here and went to my wife’s family’s Fourth of July thing, everyone was like, “Hey, you fucking Brit.” I was like, “I don’t understand what’s happening… Why is everyone really angry?” I understand Fourth of July as Independence Day, because Bill Pullman said so in Independence Day. [laughs] I don’t associate that with actually being something. But to [Americans], it’s huge. It’s everything.

What surprises me, to be honest with you, because it so important—and it should be; independence was born—is that people don’t know how it came about. They don’t actually understand that Washington was really getting his ass handed to him almost daily by the British. If the British had just pursued him and actually stamped him out, they would have won. There were several times when all Britain had to do was keep pressing, but for some reason, England went, “No, we’ll wait. We’ll just chill here for a second.” It’s just so English. The fact that these guys on our show, the Culper Ring [of spies], these ordinary people did something incredibly important, which ultimately led to that independence and to that celebration, it’s kind of wild. I started talking to people from my wife’s family who are educated and from the South—from North Carolina. I’d be like, “I’m making a show about the Culper Ring,” which I thought obviously everyone would know what that meant. And they looked at me like, “What are you talking about?” That was also an education for me. I was like, “How do you guys not know about this?” It just surprised me.

BROWN: Do you feel like being a spy in the 18th century was fundamentally different from being a spy today?

BELL: Yeah, completely. We’re sort of desensitized to it now; we almost just accept that it happens. It’s probably happening right now. [laughs] This phone line, for example, is not particularly secure. Your credit card, your inbox, your Hotmail.com are not particularly secure. We are being watched; it’s just a part of life. But back then, they didn’t know how to do it: “So you want me to listen to someone, somehow get the information and remember it, and then pass it off to someone who’s going to give it to you? It’s going to take about three weeks for me to overhear something and for you to understand what it is. How do we even go about mechanizing how information gathering and delivery is going to work?” I think that is the thing that is quite interesting about the show: they’re dealing with something that we are all so used to today. It’s a weird thing to take for granted, because it’s kind of fucked up that we’re being spied on all the time. But for them, it was a brand-new concept, a brand-new idea to try and win their freedom and get their natural rights back. It was an essential tool that they had to learn. So I find that interesting.

BROWN: And was it frowned upon as ungentlemanly?

BELL: It was incredibly dishonorable. Especially for someone like [my character] Abe Woodhull, who has a family. Let’s say that you commit a crime, you get caught, you might get sent to prison. It’s going to be bad. But if you get caught spying, you’re literally hanged the next morning. It’s such a perilous mission and it’s such a risk. And over what? No one knows who the fuck this guy is. [laughs] He did this incredibly courageous thing, and still, to this day, there isn’t a marble statue of him anywhere in D.C. There isn’t a book written about him, outside of maybe Alexander [Rose]’s work and a couple others. He’s completely anonymous. I guess that’s the trademark of a good spy. If we know who a spy is, that means he wasn’t very good and he’s probably dead. But saying that, it’s such an odd thing that he took such a risk and yet we have no idea who he is or why he did it.

BROWN: Is there any other character from the show that you’re particularly interested in, aside from Abraham?

BELL: Historically, Washington’s an interesting guy because I think the Washington we know from the one-dollar bill or the portraiture of the time—these fantastical chief, almost superhuman type of images—I’m sure he was nothing like that. So I’m kind of fascinated by him. There’s a character in our story called Captain Simcoe who was quite maniacal and horrible. I just enjoy watching him though, so that’s more our show than it is actual history.

BROWN: Abraham has a very tense relationship with his father on the show. We are told that his older brother died, and Abe had to transition from the second son to the first son—do you think that is the root of their strained relationship?

BELL: It’s for a couple of reasons. Fundamentally, he will never get his father’s approval; I think that’s where everything stems from. He will never get the approval of the most important man in his life. Then, to break it down from there, there was obviously another brother who died tragically and he was the more favored son—he was going to go into the military, he was very loyal to the crown, he followed his father’s politics and was probably going to end up as a magistrate just like him. Abe was just not that. He was probably more like his mother. He had a green thumb, he was somebody who liked to watch things grow—the hippie child. Abe also believes that he should be governed by his own people; he should be able to make his decisions in his country, whereas I think his father isn’t of that ilk. I think for both of them, they’re trying to position themselves on the right side of history as history is literally unfolding beneath them.

BROWN: I’ve heard from quite a few people people that shooting a show with one-hour episodes can be really grueling. Has that been the case with Turn?

BELL: Yeah, it’s horrible. These actors who are phenomenally good in these shows, who give such nuanced performances—Kevin Spacey or James Gandolfini—it amazes me. Our schedules can’t be that dissimilar, and there are so many highs and lows of an episode, so many important and valuable scenes that you have so little time to focus on and to deliver the goods on. It amazes me when you see television work and you’re like, “Wow, that was incredible.”

BROWN: Were you aware of how difficult it would be going in?

BELL: I don’t know, because on the pilot you get a bit more time; it’s almost like they blind you with the pilot—”We’ll do it in three weeks,” so you’re like, “Oh, this is just like a movie. It’s a little bit quicker than a movie; I can handle this. The scene count per day isn’t that crazy, the page count per day isn’t that crazy.” By the time you’ve got a series, you’ve whittled two and a half, three weeks down to eight days and you’re like, “We can’t do this! We can’t shoot 10 pages in one day, are you serious?” And then you do and you’re like, “Oh, I guess you can…”

I was very frustrated a lot of the time because I wished we had more time, but I’m just a complaining actor. [laughs] There’s nothing unique about what I’m saying. A lot of people probably feel the same way, but it’s the nature of the beast. Sometimes great things come from doing things quickly and not over-thinking stuff.

THE NEXT EPISODE OF TURN WILL AIR THIS SUNDAY AT 9 PM. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT THE AMC WEBSITE.