Gwen Ifill

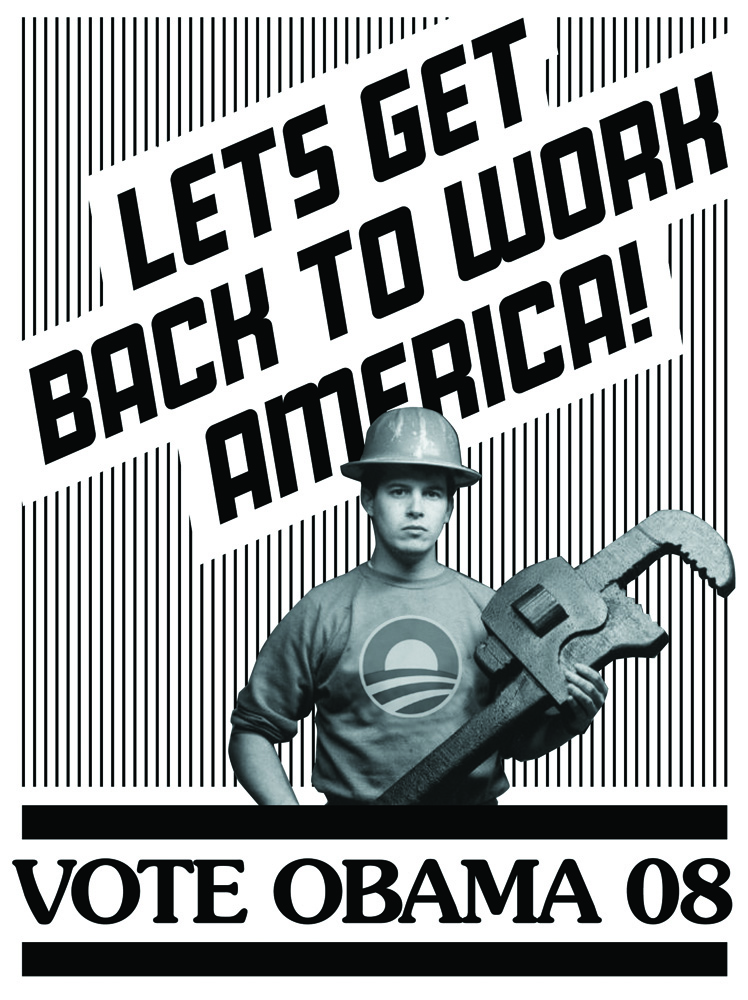

As the country swears in its first black president, a new book explores the complex conundrums of the race card in 21st-century American politics.

Gwen Ifill was born in the mid-1950s, before the civil rights movement, when no one could imagine that before the 20th century was out, America would have black television news anchors, senators, and governors, let alone a black president early in the 21st. A familiar face in network TV news (and before that a respected newspaper reporter), Ifill was chosen to moderate the 2008 vice-presidential debate between Joe Biden and Sarah Palin, which stirred some controversy when it became known that she was in the process of writing her first book, The Breakthrough: Politics and Race in the Age of Obama, to be released on inauguration day.

Although The Breakthrough is not solely about Barack Obama and his quest for the White House, his election as America’s first black president certainly gives Ifill’s book a timely quality. Her central argument, as she profiles black leaders such as Newark mayor Cory Booker, Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick, and other lesser-known politicians, is that the black political structure formed during the civil rights movement has given way to a generation of men and women who are direct beneficiaries of that struggle—Obama first and foremost among them. I caught up with a very busy Ifill as she was finishing her book in the days following the presidential election this past November.

HOOMAN MAJD: A week after Barack Obama was elected, Maureen Dowd wrote in her column for The New York Times that she had heard a lot of white people asking black people what it feels like for them now that we have our first black president. So I’m curious: Did Maureen, who you’re friendly with, ask you that question? And if so, what is your response to it?

GWEN IFILL: You know, everyone has asked me that. I think that I took Maureen’s column differently than some people. I didn’t take any of that part of the column to be about things that she actually did. So she didn’t literally pick up the phone and call me.

My favorite post-election line came from The Onion. The headline read: ‘Black Man Given Worst Job in The World.’ Gwen Ifill

HM: I think she was alluding to how condescending and patronizing that sentiment is. That said, I’ll be condescending and patronizing: What does it feel like for you, as a black American, now that we have our first black president—especially given that you’ve written a book on race and politics?

GI: Well, you know, every black journalist I know lives several different lives. We all kind of live in this work world, and then we live in a personal world, and the personal part of me is able to step back and be awestruck by what’s happening. You know, my father marched in civil rights marches. One of the reasons I’m a journalist is because I grew up exposed to how change in the world could affect my life directly. I understood that it made a difference to me if there was a Civil Rights Act, because it meant that it would make my life easier. So on election night, when they announced that Obama was president, I was on the air reading through the exit polls, and I consciously stopped so I wouldn’t miss that moment. And then I started reading the exit polls again. [laughs]

HM: Of course. You went back to your job.

GI: Exactly. So these two things can kind of coexist in your head. The funniest part of the small kerfuffle that happened around the vice-presidential debate [between Joe Biden and Sarah Palin], about me writing the book, was that the people who got worked up about it had their reasons, but what was underlying all of it was this idea that a person cannot hold two thoughts in his or her mind—that journalists can’t vote and be fair.

HM: I wanted to ask you about the VP debate, because you were accused of having some bias and I assume that bothered you. Is that the reason that you were, at least in the minds of some people, relatively easy on Sarah Palin?

GI: But here’s what people who made that judgment failed to note: It was a debate. It wasn’t an interrogation. I was supposed to have questions for Joe Biden, too. And people who say I was easy on Sarah Palin failed to note what my job was that night.

HM: Well, I think what a lot of people were reacting to was when Sarah Palin said that she wasn’t even going to answer your questions. Did you not feel tempted at that point to, maybe not scold her, but suggest to her that her answering your questions is the whole point of the debate?

GI: No, because then folks would’ve been saying, “Oh, look. She’s going after her.” Here’s the way I approached that debate, which is the exact same way I approached the vice-presidential debate I moderated four years ago between Dick Cheney and John Edwards: I approached it with the assumption that people at home watching are pretty damn smart. So, for instance, I asked Dick Cheney and John Edwards to answer a question about domestic incidences of AIDS among black women, and neither of them knew the answer. And I discovered in the weeks that followed that people didn’t say, “Why didn’t you beat up on them and make them answer the question?” Instead, the response was, “Thank you for showing us that they didn’t know the answer to the question.” People got that it wasn’t my job to chase them around the table. So I didn’t think I needed to shake my finger at Sarah Palin and say, “Young lady, answer my question.” I think people are smart enough to pick up on what she was up to.

HM: So what effect do you think the election of Obama will have on this politically correct culture? In the book, for example, you talk to the mayor of Sheboygan, Wisconsin, who was at great pains to tell you that he has black friends. Do you think that kind of attitude is going to slowly disappear?

GI: No. And I bet you that Barack Obama doesn’t think it will either. I talked to scores of people for this book, many of whom are very much like Barack Obama in their worldviews, in that they think race should not be the primary driver in our decision-making and our discussions. But if we talk about health care, for example, then it will affect the black community. That’s the attitude of people like Cory Booker and Artur Davis [congressman from Alabama] and a whole generation of folks. None of them, however, believes that that means racism is over, or that other people are going to stop judging you because of race. The questions are: How do we get past it? And how do you still achieve what you got into public service to achieve without making it completely race-driven?

HM: But a lot of Americans seem to have bought into the notion that the color of one’s skin shouldn’t matter in politics—or in any area of life.

GI: Well, it’s not that it shouldn’t matter, it’s that it shouldn’t be the primary driver. I think that a whole lot of people who voted for Barack Obama will tell you that it matters. But the question is whether race is a disqualifying feature. My favorite post-election line came from The Onion. The headline read: “Black Man Given Worst Job in The World,” which kind of plays into this notion that once things are truly screwed up, then what the hell? We might as well give it to the black guy. [laughs]

HM: In your book, you talk a lot about the way Obama ran his campaign and the person he is, which you contrast quite well with the previous generation of black leaders who were involved in the civil rights movement.

GI: I’m not sure it’s solely a generational line. I could find you half a dozen young black activists who still think that race is the primary driving issue, who are not in lockstep with Obama’s approach. There’s the leftist academic community that is actually wary of Obama’s approach. I don’t think that any one thing, one election, one breakthrough changes everything. I don’t think that Obama thinks that either. It just means that we’re open by degrees to a different way.

HM: I can’t speak for black people, but—

GI: That goes for both of us—I can’t speak for black people either. [laughs]

HM: Well, I mean, I can’t speak as a black person, but Obama’s election has to be more momentous than anything else in the history of blacks in America.

GI: Of course, it’s momentous. He’s president of the United States. It’s a big deal, there’s no question. But I don’t want to overstate that because we don’t yet know what kind of president he’ll be. And so the breakthrough in and of itself isn’t the victory.

HM: You’re very cautious.

GI: Well, I’m a journalist first and foremost, so I don’t get too caught up. But I do think that nobody saw this coming. I might not have admitted this at the time, but early on I didn’t think Barack Obama could be elected—although I didn’t think Bill Clinton could be elected in ’92 either. But with Obama, part of it was that I kind of told myself not to think that far ahead and not to be predictive, and then part of it was also that it did seem inconceivable at points that he could win. When it started to look like he actually could win, most of my black friends were still very pessimistic about it—even after every poll showed him to be ahead. I think my father would have felt the same way too. The history of African-Americans in this country is such that you don’t get your hopes up. But in my case, it really had to do with training myself to not look too far ahead, because then it becomes impossible for me to see what I’m looking at in the moment.

HM: But you were also writing a book during this period, which you obviously hadn’t finished.

GI: I never thought of my book as being about Obama, even though how he fared in the election would affect it. But I did have the idea that Obama was not alone knocking around in my head and that I had been covering people like him for so long. Whether Obama won or lost, my understanding was that this book would tell the story of this generation. One of the most interesting things for me about Barack Obama is that he found a different way for a black candidate to get elected. He was not, for example, going to pay walking-around money to poll takers in South Carolina to get people to the polls. He wasn’t going to go into black churches and say, “I will do anything you want.” He was not going to play by the rules—in fact, he was not going to go out of his way to even identify himself as black. He leaned so far against being identified by race on the understanding that everybody would know his race. He didn’t need to identify himself that way because people could look at him and see that about him. And it worked, because the assumption there—which some people think is cynical—was that the black vote would show up because he more or less represented their interests and had a measure of race pride that could drive up the turnout without him having to be overtly black. And the key to getting elected in this country is still getting the skeptical, independent, white voters. Keep in mind that both David Axelrod and David Plouffe, who ran Obama’s campaign, also ran Deval Patrick’s [gubernatorial] campaign in Massachusetts the same way. They looked at things and thought, We could talk about your race, but all that does is point out your differences. So what they tried to do—and succeeded by doing with Obama—is say, “You’ve got a funny name, you’ve got big ears, your father was born in another country . . . We’ve got enough working against you that’s different. Let’s see what we can do to create a persona that’s more similar to the average American voter.” And without that, he couldn’t have gotten elected.

HM: What do you think of the reactions by some of the civil rights leaders of yesteryear, like Jesse Jackson or Al Sharpton, who are now very supportive of Obama but who initially seemed to harbor a certain amount of jealousy?

GI: In the book, I call it “sandpaper politics.” It’s what happens when change happens. It’s what happened when the Irish took over from the Brahmin in Boston. Whenever a new group says, “Okay, now it’s our turn,” there’s always resistance from the people who have to give up power. There is generational friction. And there’s power friction. But that kind of thing happens in every community, in every political movement. I don’t think it’s personal. There’s always some point where people have to step aside and hand over the baton. The question is: Do they have to have it torn from their hands? I mean, Artur Davis is a congressman who is considering a run for governor of Alabama, and he’s facing that same challenge with the old black leaders in Alabama who all endorsed Hillary Clinton. He was one of the first ones out of the box for Obama. He was challenging their primacy. You know, Al Sharpton spent plenty of time on the phone with Barack Obama, but he was smart enough not to get out in public for him. He knew that would hurt. Jesse Jackson said some things that were unuseful to the Obama campaign, but he was trying to make a larger point, which often gets lost on cable television of, how do you speak to the black community? Are you going to still be a spokesperson for our issues? And that got lost because he said it the wrong way. But that’s exactly what the issue is for a lot of people.

HM: Much has been made of the international impact of Obama’s presidency. Your book isn’t meant to specifically address that point, but as a reporter yourself who deals a lot in covering foreign affairs, what does this all mean to the world?

GI: Nothing happens in a void, and what Obama is walking into now is a presidency—and a nation—that has largely become unpopular. And in some ways he’s being embraced by all kinds of cultures around the world, mostly because he’s not George W. Bush. But every good plan meets its first test when reality hits. I mean, everyone is going to have demands and expectations, and there’s no way that he can live up to all of them—or that he’ll even want to. That’s why they call these kinds of periods honeymoons. You’ve got to enjoy this moment where the world believes you’re God. And then the work begins.