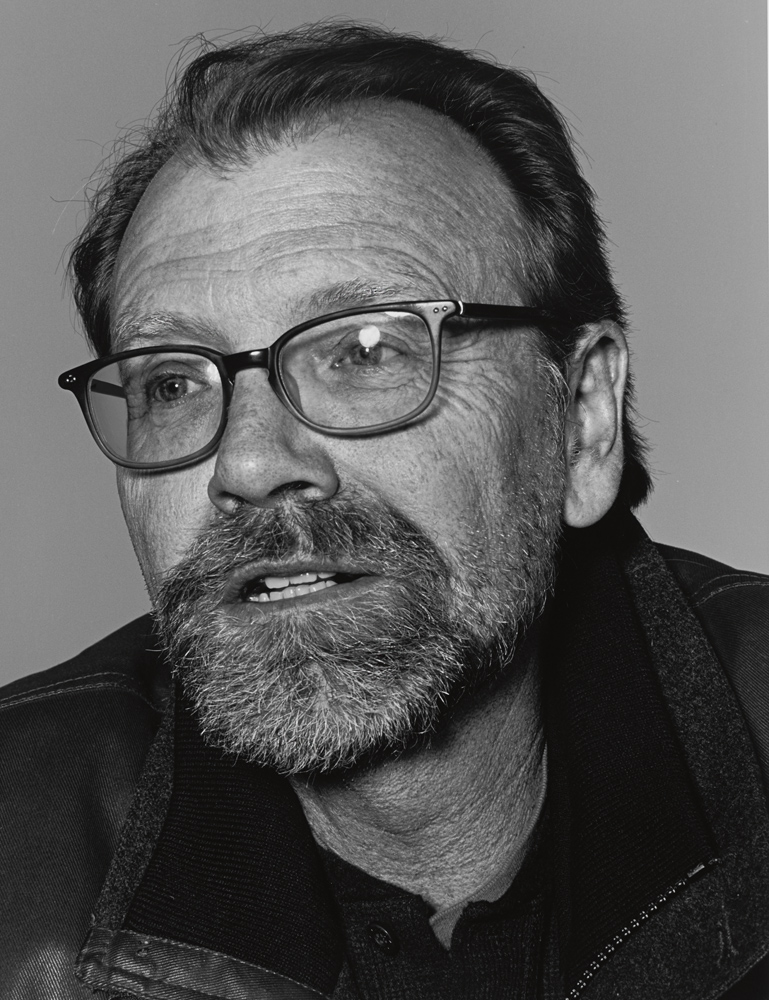

George Saunders

Some writers work within a tradition, and some create a world from whole cloth. There aren’t many who can do the whole-cloth bit, but George is one of them. Within the universe of American writing, there really is a continent called GeorgeSaunders-Land, where the people speak funny, and the social contract has either broken down or been bent out of all recognition, and our most intimate lives feel like reenactments of something we maybe saw on TV. If he were just a vicious satirist, he would still be hugely enjoyable, but what sets him apart is his willingness not only to go into the heart of darkness but to suggest possible routes out. The cool kids don’t dare do that, but George always has, and without sanctimony or even a hint of righteousness. I once heard him describe satire as “the inverse praise of good things.” Seen from this perspective, George’s career has been a 20-year praise-song to the power of language, the grandeur of the visible world, and the awesome possibility of genuine enlightenment. That we can even see this through the parade of holy fools, venal idiots, smiling demagogues, degraded environments, and twisted corporate spaces he has presented us over the years is a testament to his extraordinary skill.

But in Lincoln in the Bardo, in my view, something more has happened, though I’m finding it very hard to verbalize. Good luck, reviewers! To me, it felt like reading my favorite bits of Kierkegaard or listening to Lauryn Hill take 1 Corinthians and turn it into that exquisite song “Tell Him”… It is a work that re-creates within you the emotional and mental processes it describes. It is not a “reading about x,” it is a going-through. Lincoln is about, among other things, grief and rebirth, and it goes through you that way: You shed one way of looking at the world and emerge with another. I always thought George was among the greatest American novelists, but until Lincoln—having never actually having written a novel—he wasn’t exactly helping my case. Now the Nobel folks have no excuse. Not that work this good even needs gongs from Sweden. It is better than the somewhat shabby world it finds itself in—it is the thing in itself—and any attentive reader will find its wonder for themselves.

ZADIE SMITH: I’m a little anxious. It’s hard to know where to start.

GEORGE SAUNDERS: I feel nervous because I revere you so much. I don’t want to be stupid. If I say something stupid, just interrupt me.

SMITH: I will immediately. [Saunders laughs] First of all, when I was reading your book, the pages weren’t even connected by a staple. You sent the pages to me wrapped in an elastic band.

SAUNDERS: That’s how I like it. That’s most ideal.

SMITH: And because I didn’t want to carry the weight of it in my bag, I would read a page and then scrunch it up and put it in the trash. [Saunders laughs]. So I finished the novel and had this tremendous emotional reaction but with nothing to show for it. I couldn’t show it to Nick [Laird, Smith’s husband] or to any of my friends. It was like a kind of dream that I’d had. It was a very odd experience.

SAUNDERS: That’s perfect.

SMITH: It vanished in the act of reading it. I went onto Goodreads because I wanted to find somebody else who had read this book. There were only eight or nine people who had at that time, and they were having a kind of spiritual convening. Normally, it’s 30 people on there bitching about a book. But this was like a church meeting. It was very moving. And finishing it, I’d become part of this small community of readers.

SAUNDERS: Well, I hate to disappoint you, but seven of those were my mother. [both laugh]

SMITH: My first question is about the ending. The last page of this book—without giving too much away—involves somebody entering somebody else. Not in a sexual way. But it says one of the simplest things you could ever say, which is that we must try and be inside each other. We must have some kind of feeling for each other and enter into each other’s experience. Novels and stories are sometimes very complex staging grounds to say, in fact, very simple things. Things impossible to say otherwise because they are repeated in so many exploitative contexts—adverts and TV shows and political speeches.

SAUNDERS: To say a factoid is one thing and to demonstrate it by embodiment is a different thing altogether. And we’ve become very, very addicted to the first thing. I have a lot of theories about the beneficial effects of fiction, but I’m always trying to get away from them a little bit because—

SMITH: Because they’re really unfashionable.

SAUNDERS: Yeah. We watched a documentary last night about the immigrant crisis around the world. And it does make you blush at all the times you’ve stood up on the stage and given your speech about the healing power of fiction. But as the writer of this book, what I loved was the feeling of having so many surprises come at the end that I hadn’t really planned or planted. Just through the process of trying to make the living and the dead feel real, all these little benefits came out. And these benefits turned out to be much more articulate statements of what I really believe. And somehow they were more convincing because they were arrived at at such length. Does that make sense?

SMITH: One thing you learn about the novel as a form is that it’s always smarter than you are. The novel leads you places that you never could have gotten to otherwise. Not that I’m saying you’re an idiot, George.

SAUNDERS: [laughs] No, you’re right. And that’s also the pleasure of the novel. I have an idea why that happens, but I want to hear why you think so.

SMITH: My opinion has changed. When I was young, I was very technical about these things. I didn’t like to admit to any intimate relation with what I was writing. [both laugh] It seems to me now that the deep structures are often subconscious and set in childhood. For me, it might be something very simply to do with the split in my family. That’s why I’m always thinking about opposites. It’s so childish, really, but that might be simply what it is. What about your deep structures? Where do you think they come from?

SAUNDERS: My only take on that idea is that, for me, it all happens in revision. And it happens best if I’m not thinking in any big thematic or conceptual terms—especially in this book when I was trying to make the voices more active, more energetic. A lot of the decision-making had to do with things like: “Well, what should abut against what? What transition is more meaningful? If I cut these three lines out of this speech, how does it rest against the following speech?”

SMITH: There’s a little interview in the back of the book where you talk about thinking of the role of the novelist—in the case of your novel—as a kind of curator. But to me that’s what novelists always are. I never bought the idea of individual genius from which the novel spews forth. It’s always an act of curation. But you orchestrated this novel in a particularly fascinating way.

SAUNDERS: Yes, whole swaths of the book are made up of verbatim quotes from various historical sources, which I cut up and rearranged to form part of the narrative. This was only way I could get in some (what felt to me) necessary historical facts. But I resisted this at first, because I had this sort of prideful, juvenile idea—it might be a male thing—that every line had to shine with my inventiveness. And actually it was funny … There was one sequence of days when I had halfway decided to use the historical nuggets, but I wasn’t quite sure it would work. I’d be in my room for six or seven hours, cutting up bits of paper with quotes and arranging them on the floor, with this little voice in my head saying, “Hey, this isn’t writing!” But at the end of that day, I felt that the resulting section was doing important emotional work. Later, I went one step further, by putting in some invented “historical” bits. And reading those alongside the actual historical bits was like looking into a sort of a painful mirror, because “my” parts were so show-offy at first. They stood out because they were so flamboyant. So I had to go in and do the work of toning them down in order to make them fit. It’s like if you’re an actor and you’re always overacting, well, you’re a bad actor. But if you’re an actor who subdues yourself to the extent that’s necessary, then you’re really acting.

SMITH: I know a lot of people who read you think: “George is so much fun.” There’s no denying you’re fun to read, but as a writer I think of you as, in fact, not a fun and freewheeling type but really an obsessive control artist. You’re very precise about what you’re doing. There isn’t a thing left to chance. So when you decided to write a novel, I was very curious how that precision would translate because there’s a perception that novels can’t usually allow for your kind of absolute attention to detail.

SAUNDERS: It’s not a long book. And that meant I could obsess over it and live in it both backwards and forwards and hyper-control everything. The beginning is strange, and I did a lot of work calibrating that so that a reader with a certain level of patience would get through it and in the nick of time start to figure out what was going on. In a short book, you can do that. I sometimes think that I can’t do the bigger thing that you do so beautifully, as in Swing Time, with so much world in it and so much rapturous paint thrown around. I don’t think it would be possible to write a book on that scale with as much OCD as I have.

SMITH: I was thinking about the generation before us—a bit before us, I suppose—like John Barth and all of those pomo dudes who had that idea of, instead of hiding the structure and making it look organic and natural, we’re going to put the structure on the outside. But most of the time, at least for me, all I could attend to was that act of structural self-consciousness. Now, what you’ve done here is put the structure on the outside, but it’s created a deeper fiction. It’s more emotionally intense.

SAUNDERS: From the beginning, I actually had it in mind not to write a novel. I’d kind of gotten past that point where I felt bad for never having written a novel, even to where I felt really good about it, like I was a real purist. And then this material was around and I approached it, but almost warning it, like, “Do not try to bloat up on me because we’re not doing that; we’re not writing a novel. We’re not going to suspend all the usual rules of composition that I have accrued over the years just to get past the 130-page mark.” There were several points where I would kind of turn to the book and say, “Get thee behind me.” I don’t think real novelists do that. But I make a distinction between prose that’s very efficiency-minded (like, the minimum I can get away with), versus loosening the screws and letting the words spill out beautifully and so on. I don’t really write beautifully naturally, unlike some people in this conversation. I don’t feel like I have the intelligence to really inhabit a consistently high level of prose. I have to really squeeze it to make it into something. It blew my mind, reading Swing Time, that I could take any sentence in the book, and it was one of the most beautiful sentences written in English, and you grafted all those sentences into this incredible, multi-continent, epic. Such a vast and expansive book. It made me a feel a little bit like when I used to read David [Foster] Wallace. Like, “I can’t play that game. I wish I could, but I can’t do it.”

SMITH: The young people have a phrase for this now, which is “slay in your lane.” [both laugh] That’s a very important principle of writing. You have to work out what it is you can’t do, obscure it, and focus on what works.

SAUNDERS: Yeah, that was the first 40 years of my life. But what was fun for me with this book was to start out with the principle that went, “We’re going to fight every day to make this not a novel; make it too short to be a novel.” And then with that principle in place, the book sort of starts to say, “Okay, but I really need this. I really need some historical nuggets.” And you’re like, “All right, but keep it under control.” Or the book says, “I really need this sci-fi device of a ghost inhabiting another person.” You say okay kind of begrudgingly. So the structure seemed informed by need and efficiency. There’s not a lot of whimsicality in the form, not a lot of indulgence allowed. Like when I was younger, I would sometimes go, “Oh, every other section will be narrated by a chair.” [Smith laughs] Or, “It will be a double helix shape!” That never really worked. I guess what I’m trying to say is that whatever weirdness was going to be in there, I felt, had to be earned. And it had to be required by the emotional needs of the book.

SMITH: What interests me in it is a slight perverse balance between the sublime and the grotesque. Like you could have landed only on the sublime. But my argument is that the sublime couldn’t exist without this other half. For example, you have these grotesque, hilarious, profane ghosts in the book. Even the concept of talking ghosts is, from an aesthetic point of view, grotesque. It’s not in good taste to have talking ghosts in a grown-up novel. [Saunders laughs] But you seem compelled by that risk in order to get to the other end of the equation.

SAUNDERS: I think it’s also a kind of a psychological thing. As a kid, I had a real fascination with perverse, off-color, and kind of risky things, and I also had a very sanctimonious Catholic, purist side. For me, things were either very sullied or very pure, very controlled or very under-controlled. One of the big breakthrough moments was to realize that you aren’t going to be able to excise one of those. But you are going to be able to use them against one another or in support of one another—almost like two people on a motorcycle. One tendency has to aid and abet the other, in a certain way. So if I find myself being too earnest and sentimental and hyperbolic and simplistic, which is definitely a tendency I have, then I bring in this perverse henchman.

SMITH: There’s something very Catholic about that.

SAUNDERS: Right. And in my personal and spiritual life, I reject that. I don’t believe in that. I’m always trying to get my mind into a less judgmental place, making less rigid judgments about things like “perverse” versus “pure.” But in terms of prose, those sorts of oppositions seem to work. This book scared the shit out of me for many years because it seemed to me not all that open to the perverse or funny or naughty. And I knew if I evoked that stuff too easily or gratuitously, as a way of assuaging my fears of not being edgy or whatever, the writing would fall apart. This book was going to have to have some earnestness in it.

SMITH: I have a spiritual question, and it’s going to come in a minute. But I want to ask first about A Christmas Carol, which I know from speaking to you about it is an important childhood influence on you. It was on me, too. Since Christmas Eve, I’ve watched four versions of it because my children are slightly obsessive, ending with The Muppet Christmas Carol.

SAUNDERS: Did you watch the George C. Scott version?

SMITH: Yes, and the Jim Carrey. And I watched a terrible, early-’80s cartoon version. And then I read it to them in a slightly desperate attempt to bring some meaning to the gift parade they’d had the past few days. Anyway, I was thinking about the legacy of ghosts in fiction, and specifically the moral power of those Dickensian ghosts. Because a ghost can be a very powerful but also manipulative element. For example, I do find the values in A Christmas Carol significant. It is important not to be mean and stingy and not to give up love for money. All true. But by the end of it, you could also see that there’s also a kind of a sentimental protection of capital, right? Because in the end, everybody gets to keep their money. The poor stay poor. Scrooge just gets to feel better about himself. And all is right with the world. I bring this up because I feel like your anxiety of fiction and certainly mine is exactly the limits of it, right?

SAUNDERS: Yeah.

SMITH: That it has historically been a comfort for the bourgeois and that you can read the most extreme books and not change. You can read A Christmas Carol and not change in any way.

SAUNDERS: Yes. A lot of books can probably even help you not to change.

SMITH: But something in me was changed by Lincoln in the Bardo, and the great sublime/grotesque risk of your ghosts was a part of it. Are you writing fiction with the intention of creating some change inside a person?

SAUNDERS: Well, first, the one thing about A Christmas Carol that always bothers me is that Cratchit is so sweet and perfect. He’s like an Ivy League kid who just is labeled “poor.” He doesn’t have any bad habits. He’s never cranky with his kids. But I was thinking about something I heard you say recently, about multiplicity. That meant a lot to me. When I think about what fiction does morally, I’m happier thinking of a person full of multiplicities—sort of fragmented. Maybe you could even think 100,000 people are inside each human being. And you drop a novel on that person, and a certain number of those sub-people come alive or get reenergized for some finite time. It’s maybe just for a few days even, depending on the book. Although there are books that I read years ago that enlivened things in me that haven’t died yet.

SMITH: I think we understand this experience more from being readers than writers.

SAUNDERS: Yes, that’s right. I remember reading The Bluest Eye when I was a young parent, and something opened in me. That’s the highest aspiration. So A Christmas Carol would enliven a certain subset of those 100,000 internal people. And you come out of it crying and saying, “Fuck, that’s beautiful.” And yet, like we’ve said, there are some things fundamentally off about the stance of the book. And maybe that’s okay; maybe every book is flawed, and great books, as flawed as they might be, articulate a moral argument that the reader then carries forward. The critique to this model is, of course, to ask: Should a book be ever so perfect that you come out of it with complete moral agreement that can be sustained? If that’s the case, wa-hoo, you know? Wa-hoo.

SMITH: I have some questions about the bardo.

SAUNDERS: Well, you’re speaking to the right person.

SMITH: Do you, George Saunders, individual citizen, actually believe in the extension of consciousness after death?

SAUNDERS: Yes, I do. Not for any particular reason, and I don’t know how long that state would last. Do you, Zadie Smith, citizen?

SMITH: I don’t. For me, your novel is about a problem of pain. I have a natural tendency to feel well about the world, I suppose, one way or another. But then there is the problem of pain. There are things like Lincoln’s beloved little boy dying. Children with cancer; that’s a classic one, too. To me, these kind of everyday miseries act as a fatal disqualifier. My sunniest beliefs are basically contingent on the fact that my child is not dying of cancer right now.

SAUNDERS: Yes, that’s true.

SMITH: So those beliefs about the essential goodness or beauty of the world are fundamentally paper-thin bullshit. There’s not an essential belief that isn’t a contingent belief. It could all be destroyed in a second, at any second. And I have an issue with that.

SAUNDERS: Yeah. I do, too. But maybe it’s the scientist in me that says, “Okay, if we want to have the most expansive vision of things, then we’d have to imagine the world to be made of billions of contingent moments.” And certainly we’re always rooting for our particular contingent moment to be a great one. Pain-free. But the more expansive vision has to include the idea that, even for us, sometimes our particular contingent moment is going to be horrific. So then the big moral question is: How do I live with that terrible truth? I keep thinking of Robert Stone making the distinction between the word sublime and the word beautiful. He described being in a battle as sublime. Because even though people were dying, it was such a huge sensory experience that it became sublime. The other thing that’s useful for me is this notion of the absolute versus the relative; like in a relative sense, yes, if we walk out and it’s a beautiful morning, it’s only a beautiful morning because we don’t have a broken leg or hemorrhoids or something. But then in the absolute sense—kind of from the God’s-eye view—God might feel like, “I made this thing that has all of that in it, all the horror and all the beauty.” So in a certain way, we’re always toggling back and forth between the absolute and the relative, if that makes sense.

SMITH: I used to take that God’s-eye view as a comfort when I was a child. I’d think, “Well, we couldn’t find the world meaningful at all if it weren’t for death.” Of course, that is the smuggest and most intolerable of all perspectives because I’m not suffering from the death or the pain. Yet when I was 13, I really used to skip down the street, happy in thinking, “Oh, well, someone’s suffering pain in order for me to feel this pleasure.”

SAUNDERS: [laughs] I know what you mean. And I laugh because I’m such a baby if I even get a flu. I had an experience a few years ago where I was on a plane in which one of the engines went out. And, oh boy, you talk about seeing your philosophy fly out the window. I couldn’t even remember my name. I was just repeating the word no over and over. But the reason that the contrast between the absolute and the relative is so terrible is because we believe so fully in ourselves as permanent, continuous, and central. I feel insane saying this, but if one weren’t so deluded about the permanent reality of the self, a lot of this pain would actually lessen. In other words, if you could press a button and your ego investment was less, the toothache would be less. Or less tragic at least.

SMITH: But the belief that consciousness extends beyond death is surely to put more belief in the permanence of self, not less. That seems to me a comfort that you’re allowing yourself.

SAUNDERS: Yeah. But I think the idea is that what extends is not identical to self. I’m no expert. (I have this tendency to take a little bit of questionable knowledge and riff on it.) But one of the ideas that runs through this book is this Buddhist notion that the mind is incredibly powerful; not the brain but the mind. Let’s say there’s something operating in you called Mind. It’s very powerful, but it’s dampened by the body, by physicality. When you die, that tether gets cut and off the mind goes with incredible power. And some of these Buddhist texts say that, in the moment after you die, you think of New Jersey and you go to New Jersey or you think of 1820 and you go to 1820. Also, all your sort of inner-symbology gets writ large. So, if you’re a Christian, you see Christian iconography.

SMITH: Well, that’s very Christmas Carol-y of you.

SAUNDERS: Yes. Or you might see the Kardashians if you’re a big TV viewer. That whole idea is really intriguing to me. If you took snapshots of ourselves throughout the day, the way that our mind is twisting and turning, then at the moment of death, the mind would be twisting and turning in the same way. But the Buddhists say it’s super-sized because there’s no bodily damper on it.

SMITH: There’s no impediment.

SAUNDERS: Yeah. That’s how I approached these ghosts in the book. What do the ghosts do? Well, they do the same thing they always did, but more of it.

SMITH: You mentioned in an interview a quote from the Gnostic Gospels: “If you bring forth what is within you, it will save you. If you do not bring it forth, it will destroy you.” I was thinking about that. What that has to include is the belief that people have something essential inside of them that they carry with themselves always. And I guess I’ve always written more from the opposite perspective, that kind of existentialist perspective which argues that existence precedes essence. And there really isn’t anything essential in there—you’re the product of your actions, which can always change. And they retrospectively make you one way or another.

SAUNDERS: But what do you make then of habit of mind?

SMITH: Well, when you have children, you’re certainly challenged in this belief. I always remind myself that Sartre and de Beauvoir didn’t have children. And when you don’t have children, it might be easier to believe that the child doesn’t come with something.

SAUNDERS: And especially if you have two children, like you do.

SMITH: Right. Then you really see it.

SAUNDERS: [laughs] In terms of that quote, I think it depends on what you define as “inside of” you. I hear that to mean “your essential tendencies.” One example from my life, that it took me far too long to learn, is this: I’m a control freak. I’m defensive. And I’m an egomaniac. That’s true about me.

SMITH: You’re a writer. I could have told you all that.

SAUNDERS: You should have told me when I was 10. Of course, you weren’t born yet. But that’s what’s “within” me. I take cheer from that quote from the Gospels because it means: Whatever is within you, don’t worry about it. Don’t blame yourself. Just laugh at it or urge it out into the sun. All these traits are like coins. Two-sided. All those traits—which we might want to label as “negative”—can have positive aspects, can be applied to something, can be used for something.

SMITH: But 150 years ago in Dickens’s time—and this may be sentimental—at least those coins could be more easily “cashed in.” There was at least a sense of craft. So some of the things people had inside of them, they had the possibility of expressing in the making of things—even in a daily way with their clothes or their food. People made a good deal of both themselves. Now our daily lives are almost all consumption. Craft plays a tiny role. And today, writing seems to me like an incredible luxury, almost a perversity, something which hardly exists in the world anymore, where you get to see the fruits of your actions in a daily way.

SAUNDERS: I agree with that. I haven’t written for the past three or four months, and I can feel myself getting more materialistic, more conceptual and more shallow, less generous. I think you’re right. I think when you get to export your creative impulse into something, it kind of lessens that busy energy that can be so confrontational and pissy. And it’s funny that, at the same time, we’ve invented this internet thingy that takes those very traits and super-sizes them. You take somebody who has no creative outlet and then you agitate them. And there you are.

SMITH: A lot of your early stories now feel prophetic. Take the recent election. Historians in 100 years might write about it as being the first internet election, in which what happened was actually an expression in the real world of a virtual reality. And you’ve been writing about that subject for a while.

SAUNDERS: To me, it’s interesting to think of this as the culmination of materialism. And by that I don’t necessarily just mean gathering stuff, but the belief in the pragmatic … in shareholder value, that which can be demonstrated. Distrust of ambiguity. And that way of thinking somehow bleeds over into a disrespect for truth and a suspicion of intellectual activity and so on. Curiosity understood as a sign of weakness. I think that’s what we’re seeing. But what’s really baffling to me is the way that the technology has risen up to help us become more materialistic.

SMITH: What is your relation to technology?

SAUNDERS: I’m starting to withdraw from it as much as I can. I don’t do much of the social media stuff. Like, if I’m on Facebook, it changes my relation to the real world in a way that makes me feel sick—almost like I’ve had too much sugar or something. Also, I don’t mind being criticized intelligently; although I don’t love it. But social media sometimes feels like a vehicle for one-dimensional sniping, more than true criticism. When I wrote that piece in The New Yorker on Trump, I got so many online reproaches.

SMITH: That was a wonderful piece. But of course you would have. When I see my friends engaging in a Twitter war for an afternoon, I think that would destroy me for a month. I know to argue against our online lives seems like the argument of the grumpy, old Luddite novelist, but I really always try to make the argument from the perspective of personal pleasure. Like, is this making you happy today? If it is, cool. If not, why not?

SAUNDERS: The internet kind of feels like happiness sometimes, however. It feels like stimulation.

SMITH: But there has to be a break. Addiction also feels fun while you’re doing it. But after a while, you form an accommodation with it. You make it a corner of your life, not your whole life. But I think smart kids already might be doing this.

SAUNDERS: I think the wave of social media rejection is coming. I think there will be a big reaction against it. It’s just like sugar-— mean, I loved it as a kid …

SMITH: Right. And if I were still watching TV the way I did when I was 8, we wouldn’t be talking right now because I’d be watching nine and a half hours of television today. As an adult, I decided that wasn’t the best option for me.

SAUNDERS: But that’s what’s unsettling about the current culture war. I’m from a pretty working-class background, and I really worked hard in my life to eradicate those parts of myself that were stupidly trapped in that world. Those of us who come up that way made a series of choices to benefit ourselves and make ourselves more generous and open. And I see that being looked at askance as a form of elitism now, which is really scary. When I wrote that Trump piece, I had this uncomfortable experience of sensing a lot of things that were nascent, that I couldn’t quite articulate. And one of them was this move toward anti-intellectualism. An anti-love move, even … To understand any plea for further consideration of a group you don’t know anything about to be some form of, quote, political correctness. These things are bubbling right under us.

SMITH: That’s why I found the last page of your book so overwhelming. I cried. That doesn’t happen to me very often. It was exactly this restatement of something so simple. You have this final image of—it’s going to sound crazy to people who haven’t read the book—a black man inside Lincoln riding on a horse. And for a moment, he’s also inside the horse. It’s a radical metaphor, made real. I read this book recently called Grief Is the Thing With Feathers by Max Porter. And on the last page, a character says: “I LOVE YOU I LOVE YOU I LOVE YOU.” And I realized reading it that the whole book, with all its swirls and difficulty, may have been an excuse to say those words, which are basically unsayable in fiction. You can’t say “I love you, I love you.” It’s ridiculous. And it’s like the end of your book, it has an insane and simple power that I wouldn’t have listened to in any other presentation.

SAUNDERS: But it’s interesting, when you think about it. In real life, when you have an emotional experience, it’s never just because of the thing that’s been said. There’s the backstory. It’s like Hemingway’s iceberg theory—the current emotional moment is the tip of the iceberg and all of the past is the seven-eighths of the iceberg that’s underwater. So when somebody you’ve known for 20 years, and with whom you have a full context, winks at you or whatever, it can be huge. I think in a sense what you’re trying to re-create in fiction is that.

SMITH: I have a final question for you. There’s a quote by Kafka: “There’s an infinite amount of hope but not for us.”

SAUNDERS: But not for us.

SMITH: I don’t mean to push the point, but it does seem to me from the stuff I’ve written, it hasn’t done me any good. I never feel any better. I don’t feel wise. I don’t make better decisions. It’s the same horseshit my life always has been. [Saunders laughs] The writing doesn’t help me. I think most writers feel this way. But when I talk to other writers about you, I find they think of you as the exception to this rule. They always say, “George seems happy. George has it all figured out.” I want to know if they’re right. Does the practice of writing help you?

SAUNDERS: Well, the first answer that came to mind is that it helps me in the sense that I really wanted it. I really wanted to be allowed to the table. So it makes me happy to be at the table. It sounds a little shallow, but if I imagine the shadow life, where I didn’t get that chance, and all the ways my negative inclinations would have bloomed if I hadn’t gotten the attention, but also the creative outlet … I’m not actually that happy. I mean, like you, I have multiplicities. My happiness blooms and it wilts. And there are things that are shadow sides of the creative energy that are negative and all that kind of stuff. The only thing that I say to myself is, in the spirit of that quote from the Gnostic Gospels: Writing is a way to let all that stuff out into the sun. Even if something within me is ugly, writing is a pretty good place to play with that thing and to begin to really see it. The other thing I’ve discovered that is a help is that there isn’t a simple virtue or a simple vice. They’re always connected. If you have Tendency A, that you loathe, you can almost be sure that Tendency B, which you love, is somehow connected to it.

SMITH: But you never feel writing these books … That’s what I have to confess, I often feel, “What’s the point? Why am I doing this?”

SAUNDERS: Oh, no, I totally feel that. I think part of the reason I do it is because while I’m doing it, I don’t feel it.

SMITH: Yeah, that’s maybe the only time I don’t feel it.

SAUNDERS: But I think that’s okay. I don’t think that’s a failing. I think it’s just a feature. Like, a feature of oneself. It’s almost like those boats that sit really low in the water; they look kind of ugly. And then you get one of them up to 80 miles an hour and the hull comes up, and it’s a beautiful thing. I’m okay with that for myself. I have to be, because I know it’s true. Like when I’m not writing, I tend to get depressed and a little bit surly. And then when I’m writing, suddenly I feel enlivened. Now the only thing as I’m getting older that I notice is that it’s a pattern. It’s like drugs. I’m always nice when I do drugs. [laughs]. But, you know, I’m nicer on the drug called “writing.” But honestly, the choice is: I can be a cheerful person, more awake to correction, more of a force for good … when I’m writing. Or I can be the opposite of all those things, when I’m not writing.

SMITH: I said that was going to be my final question, but I have one more about posterity. It’s that Woody Allen quote: “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work. I want to achieve it through not dying. I don’t want to live on in the hearts of my countrymen. I want to live on in my apartment.”

SAUNDERS: The other one he has is: “It’s not that I’m afraid to die, I just don’t want to be there when it happens.”

SMITH: Right. Now all these famous people have died recently. Something about famous people dying causes an interesting mass reaction. [Saunders laughs] And some of the people who died were kind of epitomes of a certain effect. Like George Michael and Bowie and Prince, for example; they had this communication with so many other minds. It’s not something they’re present for in a weird sense. Prince can’t really know how “Darling Nikki” is fused with my teenage memories. But it’s a communication from which I hugely benefited, even if Prince gets nothing out of it (except money and fame). How do you feel about the idea that you’ve had a communication with all these minds? Is it something you can think about at all?

SAUNDERS: No, it helps a lot. I love it. I was thinking the other day about the idea that you have a reader and a writer, and they’re different and they’re flawed and they’re fucked-up, each in their own way. And most times they’re in the middle percentile of human goodness. They’re just who they are. Then, in the moment of reading, the writer comes up to the surface and the reader comes up to the surface and they kiss, like two fish. That actually does happen. We know that happens. They’re both briefly their best selves, or at least better selves. A flawed human being writes something and 60 years later a reader picks up the book and something in them rises to meet it. And I believe that, when this happens and the reader goes out into the world the next day, there’s some alteration that might possibly inflect the person positively.

SMITH: I remember Wallace telling me, once when I said something along those same lines, “Stop talking that John Gardner shit.” [laughs]

SAUNDERS: Oh, but he was such a believer in that too, though. And moving toward it, I think, too, in his work.

SMITH: The older I get, the more I feel strongly about this: that that little nudge of the moral, if that’s what it is, which cannot be measured and you can never be sure of, is a far smaller thing than the personal relation that you have with humans in the world. I can’t put writing anywhere above that. There are too many of these totally awful writers, who destroyed their loved ones for their work. The idea that their writing is an excuse or an explanation or a defense for the rest of their behavior is to me obscene.

SAUNDERS: Yeah, I reject that. Especially because you see young people sometimes trying to enact the assholery even before they do the work. But I think if someone could demonstrate to me that fiction did no good, I would still do it, because I think it does good for me. I don’t know about transformation. But scientifically you can say: Well, it doesn’t seem to hurt anybody. Personally I’ve been cheered by books at really critical moments. That much I believe. You were talking about the last page of that book and idea that fiction sometimes is an elaborate kind of support for a fairly simple idea. One of the revelations in that book for me was this idea about citizenship. Even that word—citizenship—for someone my age, it makes me cringe. But, to me, the political space we’re in now argues for a reboot of fairly simple ideas and the examination of the way that Americans have not been living into them. The idea of inclusion has become kind of a stone that we’ve passed our hand over so many times that it doesn’t mean anything. But while writing this book, it occurred to me, you either believe in the Constitution or you don’t. If you do, it’s intense in what it wants of us.

SMITH: But George, isn’t there the worrying reality particularly in America that you could believe in something entirely—all men are created equal—and then run a system of actual human slavery alongside it and contain those two ideas in your mind?

SAUNDERS: Yes. But that’s been the great American demon from day one, that we’ve had those two ideas, and said the first so pithily while we so energetically pursued the second. It’s so ironic that you often hear these right-wing people talking about the Constitution. And yet, as you were saying, this huge contradiction is manifesting itself every day in murders and injustices towards people of color. And I would say one thing writing this book did for me was underscore the fact that this issue has never been properly addressed and it hasn’t gone away.

SMITH: And yet there are so many people who feel like it’s already been touched on enough. I heard someone on the radio being interviewed about slavery in a Southern town saying, “Oh, we don’t want to hear any more about that. It was hundreds of years ago.” And it hurt to hear that! It was like a physical pain in me. It was as if you brought up a traumatized or raped child and somebody said, “Oh, well, that happened when they were 6.”

SAUNDERS: Oh, that happened to them last Thursday.

SMITH: I couldn’t believe that somebody I was sharing a land with would say such a thing.

SAUNDERS: Yes. And this is more elitist talk, but it’s partly a failure of education. Because people in my generation don’t really know the reality of it. I learned when I was doing research for this Lincoln book that it was not unusual for the Northern soldiers to rape the former slave girls. There’s a whole unwritten history of this. And even the written history is poorly understood by most people.

SMITH: Right. Like reading Colson [Whitehead]’s book [The Underground Railroad], I learned things that I really should know. I’m 41 years old. When I was reading it, I thought, this is too extreme, you know? As if all this misery is in bad aesthetic taste. And then you realize this is a daily reality for millions of people for hundreds of years.

SAUNDERS: And even when it was reported by progressives of that time, it was so cleaned up. It was reshaped into oppression narratives that they were familiar with. Because the actual things that were going on were so unspeakable that they didn’t have the language for them. And this is the kind of lame-ass realization that people like me have late in life. But working through that material, the finger points to white sloth, basically. We have not been energetic enough—white people haven’t—in pursuing racial equity. That people, and even progressive people, have actually said a form of what that guy said, which is, “Well, that was a long time ago.” And then you see a form of passivity that I, a white guy, have certainly been guilty of. I’m really sickened by it in myself now. It’s like as if there’s an epidemic sweeping the country and you just said, “Well, that is really terrible. I’m glad that it won’t come up here.”

SMITH: I feel that it’s also an allergic reaction to self-accusation. A lot of people seem to feel it’s pathological that anyone would feel any kind of guilt about anything. [Saunders laughs] Often my characters are quite filled with guilt and regret, and I get letters from people saying things like: “Are you depressed? Why would anyone think about themselves this way?” But didn’t guilt and regret used to be pretty normal aspects of human experience? Everyone’s always saying, “Just do you.” But that’s not universally good advice. You don’t want to tell young Adolf, “Hey, just do you.”

SAUNDERS: Also I think people have come to expect that in artistic representation; that every work of art should be a work of extravagant hope.

SMITH: Self-promotion and hope, yeah.

SAUNDERS: We watched a bunch of kids movies this Christmas. I was kind of joking with our family by asking, “Is anyone allowed to die in a kid’s movie anymore?”

SMITH: No, never.

SAUNDERS: I’ve had that my whole career. People were always hedging around the question of: Why are you so dark? What happened to you?

ZADIE SMITH IS A NEW YORK-BASED AUTHOR. HER FIFTH AND MOST RECENT NOVEL, SWING TIME, WAS RELEASED LAST FALL.