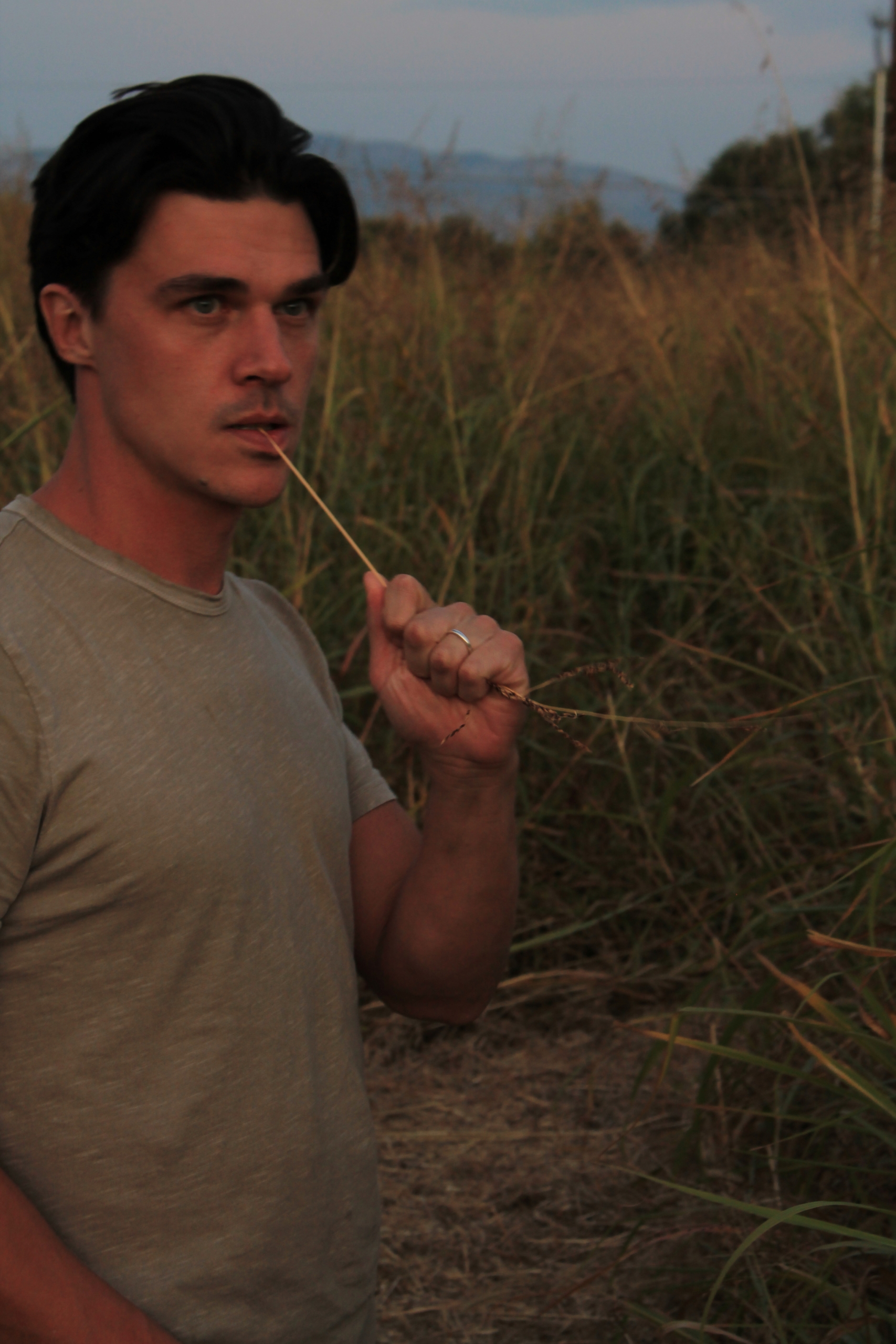

baby's first road trip

Finn Wittrock and Renée Zellweger on the Lessons of Philip Seymour Hoffman

For Finn Wittrock, becoming an actor felt somewhat inevitable. That’s what happens when your father teaches at the prestigious theatrical institution Shakespeare & Company. But from a young age, Wittrock insisted that regardless of his upbringing, this is what he was born to do. At 35, he’s proven himself right. A graduate of Julliard, Wittrock began his career on All My Children, while honing his craft in Off-Broadway productions like Tony Kushner’s The Illusion. His big break came when Mike Nichols cast him in his Broadway revival of Death of a Salesman, where Wittrock starred opposite the late Philip Seymour Hoffman. But it was his role in Ryan Murphy’s 2014 adaptation of The Normal Heart that proved to be a turning point. Since then, Wittrock has been a regular in Murphy’s troupe of actors, appearing in several seasons of American Horror Story, often playing someone with sociopathic tendencies. Wittrock’s latest foray into the Murphy-verse is as Edmund Tolleson, a convicted mass murderer opposite Sarah Paulson in the Netflix limited series Ratched. In between stops from his cross-country road trip with his wife Sarah Roberts and their baby (photos of which are included in this article), Wittrock connected with his Judy costar Renée Zellweger to discuss fatherhood, the rules of playing a sociopath, and the genius of Philip Seymour Hoffman. – ERNESTO MACIAS

———

ZELLWEGER: Where are you right now?

WITTROCK: We actually got on the road when the fires started to happen, and we just started driving. Now we’re in Chicago. We drove to Sarah’s parents, but we took two weeks to get here. We went to Phoenix, and then Albuquerque, which was actually really nice.

ZELLWEGER: Sounds like you’re going to have to write about that one.

WITTROCK: It could be a YouTube Channel. It was pretty epic.

ZELLWEGER: Have you been documenting it?

WITTROCK: Trying to. It’s hard to document when you’re driving, but we are.

ZELLWEGER: It doesn’t get much better than that in terms of backgrounds and scenery, because that drive between New Mexico and Texas is something else.

WITTROCK: It’s just so crazy to see how this country changes.

ZELLWEGER: How long did it take you to get from there across the rest of the country? I find that half the road trip across America seems to be just getting from one side of Texas to the other.

WITTROCK: Well, the thing is, with a 6-month-old we can’t go more than five hours at a time or he starts to lose it. The road trips of my youth were very different from that. There was one stop in the middle of St. Louis, and then we got to Chicago.

ZELLWEGER: Sounds like having a baby who’s got pit-stop requirements has been beneficial to your exploring America. I guess it’s your first big family road trip.

WITTROCK: As a threesome, for sure. We have not gone further than Malibu. We’ve taken him to the ocean. That was about as far as we’ve driven him.

ZELLWEGER: It’s funny, all the little lockdown silver linings. This sounds like one of them. I know that Sarah and the baby travel with you, but this must have been a really nice opportunity to just nest a little with them.

WITTROCK: There’s been a lot of nesting, for better or for worse.

ZELLWEGER: When you graduated, you were pretty much already working, and you haven’t stopped. How many years has that been now?

WITTROCK: I graduated in 2008. I did a bunch of theater right away. Two plays back to back, and then I had a real stretch. They were regional plays. I was in Massachusetts and then in D.C. I did Romeo and Juliet, and then I came back. At the time it felt endless. This is the longest I’ve gone without acting. In 2009, I got this soap opera and I got this Off-Broadway play at the same time, so I was doing this New York dream, kind of, which you can’t do anymore, but I would film the soap opera during the day, and then I would take the 1 train down to 13th Street and 3rd Avenue and do this Off-Broadway play as Troilus in The Age of Iron.

ZELLWEGER: Is that where Mike Nichols came to watch you?

WITTROCK: It was actually a different Off-Broadway play called The Illusion by Tony Kushner. I was living in L.A. and I flew out to audition for that job, and the whole time I was doing the play I didn’t have a place to live. All my friends were either living way uptown in Manhattan, or they were living in Brooklyn, so I was living on the subway between my friends. I would crash on someone’s couch, and then two weeks later would move to someone else’s house. I met Mike Nichols one night after The Illusion, and then I actually found myself back in L.A., and then found out that he wanted me to audition for Death of a Salesman, and the rest was history after that.

ZELLWEGER: I saw you in that play.

WITTROCK: Did you? I didn’t know you were there.

ZELLWEGER: I was there on closing night.

WITTROCK: Oh, wow.

ZELLWEGER: I didn’t realize it was closing night. I was in a hurry to get there to watch Philip [Seymour Hoffman], of course. But I did walk away wondering who that kid was.

WITTROCK: How funny that we would work together so many years later. I remember Phil telling a story of seeing Dustin Hoffman do Death of a Salesman, and it was also the closing night. He said that was so significant to him.

ZELLWEGER: Well, he was something, wasn’t he? As a classically-trained actor, it must have been quite an experience to share those scenes with him and watch him work.

WITTROCK: To watch him work, and watch him fall into that part, maybe to a degree that was not so healthy, but to really take on Willy Loman’s body and soul, off stage and on stage. It was intense. Before the show, you couldn’t talk to him. He’d be in a shell. He’d walk around mumbling to himself. When the curtain would go down he would—I don’t know if he was nervous, or just anxious about having people come backstage—sometimes put some part of his real street clothes on under the costume so that he could get out of costume as quickly as possible. He would be leaving the theater with the audience. He’d be dressed in his own disguise, and he would go across the street to The Glass House Tavern, and then we would all meet and greet people afterward, and then meet him there. He’d already had a table set up for us.

ZELLWEGER: Such an interesting and authentic person. I find that with every one of those experiences you walk away with something. What did you walk away with from that experience?

WITTROCK: That’s a great question.

ZELLWEGER: I mean, Mike Nichols and Philip Seymour Hoffman, it doesn’t get any better.

WITTROCK: Bob Balaban was like, “You know it’s all downhill from here, right?”

ZELLWEGER: I was just noticing, “Oh, he worked with this friend of mine and that friend of mine.” From Regina King to Aaron Eckhart to Bob Balaban to Mike Nichols. You’re my Kevin Bacon.

WITTROCK: I’ve been lucky that way. I feel like I’ve been lucky to keep jumping from cool person to cool person. I don’t know what I ascribe that to. Some kind of fate, or something.

ZELLWEGER: Talent.

WITTROCK: If you say so.

ZELLWEGER: Well, I’m not the only one who says so. Tell me what it was that you think you walked away with from that experience with Mike and Philip.

WITTROCK: I’d be doing a warm-up or something, some Juilliard shit that I had prepared before every show. I’d just see Phil reading the script. Sometimes he’d sit there for 15 or 20 minutes and just be looking at one single page. I don’t know if he was looking at one line. He was so detailed about the text. About every single word. Not about getting it perfect, but reading into it. Since that time, I have, in some way, I always keep a script on me, close to my heart like I think he did, even if I’m not shooting that day. It’s always somewhere nearby. I think of it as keeping one toe in the character at all times.

ZELLWEGER: Way back in The Whole Wide World days, Vincent D’Onofrio shared with me some of the best advice. He suggested that you don’t have so much fun when you’re working, but that you concentrate so that you don’t have to start over all the time. It’s more satisfying as a creative experience because you can begin where you left off instead of the beginning by trying to get back into the emotional space that you’re trying to play in.

WITTROCK: I love that. You don’t have to start over all the time. That’s great.

ZELLWEGER: It’s transformative, and it’s really interesting because it changes the nature of the work that you’re doing. It also gives it a different purpose, I found. It makes it easier to give more meaning to the story that you’re trying to tell, and why you’re trying to tell it becomes more significant. How did that change the work for you?

WITTROCK: I was realizing this because people were asking about my physicality with Ratched. It was so physical. Pre-Phil, I used to work more from the outside in. I used to be more like, “I’m going to try to find this guy’s walk, and this guy’s posture,” before I did any of the other work. I think post-Phil, I start from the most internal stuff, and find a way to let that affect my body. Everyone said that when he walked on stage for the first time he had a sack of weights on him, but he didn’t. He didn’t warm up. He didn’t go to the zoo and think of his character as an animal, or any of the stuff that we did, but he found a way to let the character influence his body physically in an incredibly organic way. That’s what I found exciting.

ZELLWEGER: It sounds like it’s an opportunity to experience that character’s story more authentically.

WITTROCK: Absolutely. I feel like you did that with Judy. All the physical mannerisms that everyone talked about, they were all coming from the inside out, rather than an imitation that you were trying to perfect.

ZELLWEGER: There’s an origin to every tick, or to all of the idiosyncrasies.

WITTROCK: There’s a cause to all the effects.

ZELLWEGER: Our history is in how we carry ourselves and how we move, and our personalities, and all of that. So, Ratched. What a cast. Sarah Paulson.

WITTROCK: She’s such a badass.

ZELLWEGER: Right? She’s the best.

WITTROCK: She’s worked her ass off for so long, so it’s nice to see the show and see her as an executive producer, and the number of eyeballs that are on this thing right now. It feels very satisfying.

ZELLWEGER: What is it like to go back and work with Ryan Murphy? It must be a little bit like when you do theater. You have this family of actors that you share this experience with. Tell me about that.

WITTROCK: It actually does feel like its own repertory company. There are always new people involved, and it’s always a new project, but there’s always touchstones of familiar faces. And not just onscreen, but he uses so much of the same crew and department heads. Like Lou Eyrich, who does the costumes. I met her so many years ago on American Horror Story, and she did the costumes for Ratched, which were so incredibly insane. And Eryn Mekash, who does the makeup. They’re the unsung heroes of a lot of his work.

ZELLWEGER: That’s a pretty special experience. And the characters that he writes with you in mind, he invites you to play.

WITTROCK: I think he knows instinctively that actors don’t want to repeat themselves, so he always finds a way to pitch them to you in a way that’s totally different than the thing you just did. People always make fun of me, that I’m always some psychopath on his shows, but it’s actually not true.

ZELLWEGER: You’ve played some pretty memorable psychopaths, though.

WITTROCK: I guess that’s true. But you play two psychopaths and everyone’s like, “Oh, he’s the one that always plays the psychopath.” You play five normal guys and no one says anything. It was actually at a pre-Emmy party for Versace that Ryan called me over and was like, “I have this part on Ratched. Do you know that show that I’m doing? It’s Sarah’s crazy brother. Do you want to do it?” That is literally how he works.

ZELLWEGER: I imagine it wouldn’t take much to want to say yes to playing these characters.

WITTROCK: That initial feeling you have about a character is usually going to change four or five times once the series is over. I think Edmund is the biggest example, in my experience, where it’s like, you watch the first 15 minutes of the show and you’re going to think that this guy is a complete and total monster, and hopefully by episode eight, you’ve unpacked all that, and will have a different understanding of him.

ZELLWEGER: Is that kind of work different than when you’re playing someone who has a more finely tuned moral compass?

WITTROCK: It is because I feel like I’m allowed to let Edmund go. I remember Paul Newman saying this thing about, there’re some characters that he keeps a tight rein on, and some that he lets the reins loose on.

ZELLWEGER: Wonderful.

WITTROCK: I totally get that great image, because it’s like, you think of him in Hud, he’s very tight and put together. Then it’s like, Butch Cassidy he’s free-roaming. That’s how I felt with Edmund. The reins are off.

ZELLWEGER: What are the rules of playing a sociopath?

WITTROCK: It’s coming from the script, first of all. Every scene I was in I was like, “This is a different person.” Every scene the language was different, and his approach to another person was different, and so I thought of him as a chameleon. That’s actually what some sociopaths are. They are incredibly good at imitating human emotion because they approach every situation as, what can I get out of this, rather than what do I really feel right now. I don’t think Edmund is a full sociopath, because he is capable of love.

ZELLWEGER: This is something that I’m always curious about for anybody who is a creative person in whatever medium they work in. It’s clear that you get joy from acting, but I always find that there’s something that lies beneath that. I was wondering what that is for you?

WITTROCK: It’s easy to feel irrelevant in this job. There are times when the world is going shit, and the climate is changing, and people are protesting in the street, and our president is being our president, and you feel like you should be doing something more. Then, something like the pandemic happens, and I needed to watch movies. I felt like it was survival. I think that’s what a lot of people are feeling, and it’s times like this that you realize that we do need storytellers. I think the job of an actor is to bring the big metaphysical things that the author is trying to do, and the director is trying to do, into an approachable, human, pedestrian element. It’s like you’re the messenger.

ZELLWEGER: I agree with you that it’s an opportunity to tell stories that remind us of our shared humanity.

WITTROCK: That’s it. I could have just said it like that.