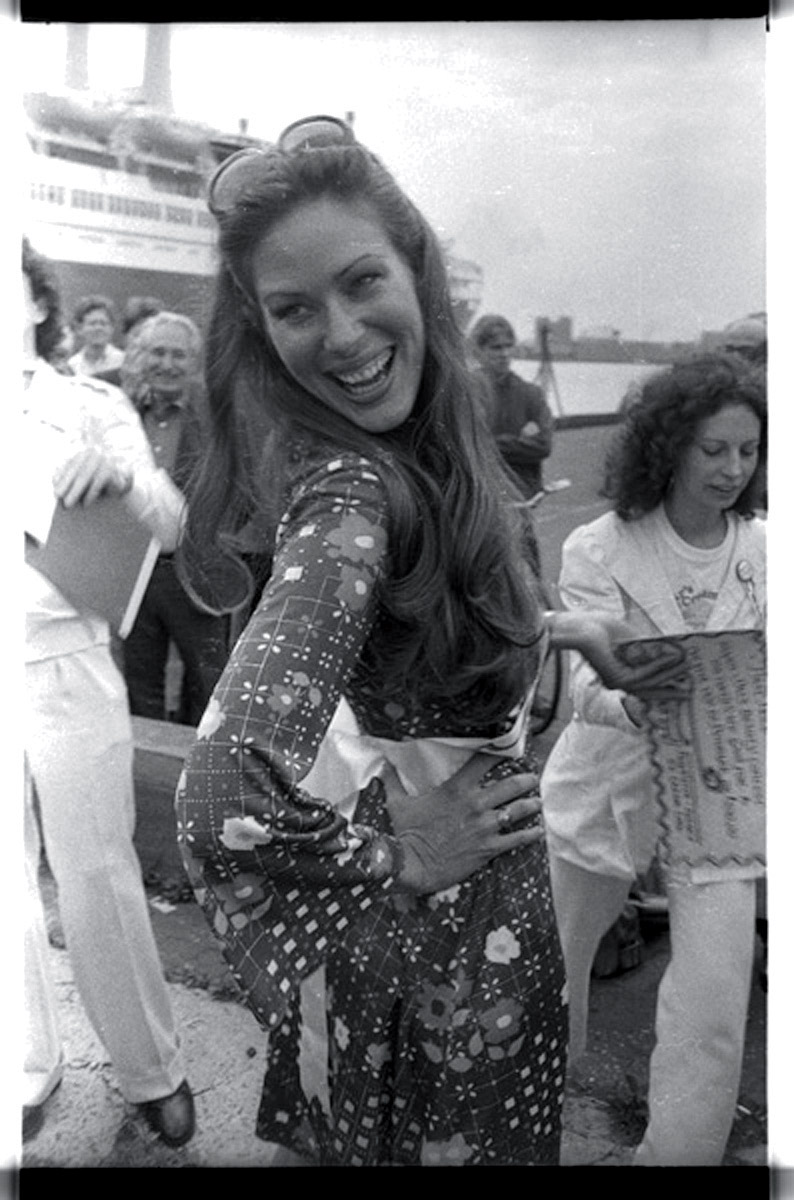

Factory Workers Warholites Remember: Mary Woronov

Mary Woronov first made her mark — more like a vivid scar — in Andy Warhol’s early films and her star turn as Hanoi Hannah in Chelsea Girls (1966). She wielded a mean whip, dancing with Gerard Malanga in the Velvet Underground’s dark circus at the Dom as the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, then moved on to Los Angeles and film work with Paul Bartel and Roger Corman. She became a noted painter, and a writer of novels and a crypto-memoir, Swimming Underground; her other books include Wake for the Angels, Niagara, Snake, and Blind Love.

GARY INDIANA: This little book that you did, Eyewitness to Warhol, is so interesting.

MARY WORONOV: It started as questions about Warhol that I was sick to death of answering. I figured, I’ll just write down the answers to these questions, I’ll publish it, and that will be the end of it. Then I ended up recounting the screen test and Chelsea Girls.

INDIANA: You have a self-interview at the end of the book. I could just ask you the same questions.

WORONOV: Just rip it out and mail it to Interview. Sign your name at the bottom.

INDIANA: For example: Does art have a future?

WORONOV: You’re kidding. What did I say?

INDIANA: That you’re too old to believe in progress.

WORONOV: [laughs] I was so brilliant then. Now my mind is a blank. It’s so glorious to get old.

INDIANA: I know. I can’t even find anything. I thought, “There’s no way I can make any more space in this hovel except to just throw everything out.”

WORONOV: Did you throw everything out?

INDIANA: No. I just rearranged everything into more festive-looking clumps.

WORONOV: Well, that I always do. I can’t paint unless I rearrange almost the entire house. It’s like a dog going around in circles before it takes a shit.

INDANA: Your books don’t seem therapeutic to me.

WORONOV: No, they’re not. They’re like — what’s that word — detritus? They’re like stuff I’m trying to get rid of, like old dead skin or bad memories.

These films were never meant to screen in a theater . . . They were meant to hang on a wall. They are Andy’s greatest paintings. Mary Woronov

INDIANA: I was looking at all this stuff about the Mole people today.

WORONOV: I love that period.

INDIANA: Well, that was the real amphetamine period. I say “real amphetamine,” because —

WORONOV: It was real. It wasn’t this stupid cocaine or anything like that. It was pure. It wasn’t methamphetamine. It was, like, real amphetamine, pharmaceutical amphetamine. It was nice and white and clean. Cocaine is sort of a rush, like, “Ooh, goody. Now let’s discuss our lives ad infinitum.” But amphetamine wasn’t like that for me. I didn’t feel like discussing anything. I just felt like, God, it’s just such a power rush. I rarely talked on it. You can see in my movies. I’m not one of the talkers. I saw a movie that I did for Warhol. It’s about Jack Kennedy getting killed, and I play Jack. I could have been brilliant. It was done on a couch instead of a car. And Ivy Nicholson is Jackie. I have to hand it to her: Mad as she is, she crawled across the top of the couch like Jackie crawled across the car. I played Jack Kennedy and I had nothing to say! Why didn’t I discuss the Cuban Missile Crisis? Ondine was trying to keep the boat afloat. But because I was so gone on amphetamine, I was just sitting there, going, “Power, power . . .” I am so pissed off!

INDIANA: But if you are getting your head blown off, you can be excused for not talking.

WORONOV: Well, that’s true. But it was boring! I hate being boring.

INDIANA: You’re never boring, Mary.

WORONOV: See that movie. You’ll change your tune.

INDIANA: Are you ever planning to write a memoir?

WORONOV: As a matter of fact, I just started writing my memoir. It’s not a memoir like Swimming Underground, which is all about my Warhol experience, and is a little fictional. Actually, it’s not fictional. It’s just a little made up so that you understand what went on. But this one is a real memoir. It’s about my acting career. It’s not about writing. It’s not about art, which means zero. The reason why it’s about my acting career is that I figured out, at this late date, I’m this different kind of actress. I’m a camp actress. I’m not a method actress, which is what Hollywood is about and what acting is about. It started in high school, where I played Caliban, the monster. Then I went to Warhol, where, obviously, it was camp acting, because it’s not really about being someone. It’s like a drag queen. She can’t be a woman. You’re not being someone. You’re commenting on who you’re playing. A drag queen comments on women, being a woman. So I was with Warhol, then Paul Bartel introduced me to the Theatre of the Ridiculous and John Vaccaro. Then I went to L.A. and Roger Corman. In Corman films there was no directing. They are too busy doing a movie to direct you. And I was free to continue my camp career. The ending, of course, is the sad fate of a cult queen. So we have the rise and fall of Mary Woronov. I don’t mind. It’s cool. But it’s an interesting thing, because there are camp actors in Hollywood, like Pacino in Scarface — that’s camp acting. You go to a T-shirt place in Venice, and there’s one T-shirt of Frank Sinatra, four T-shirts of Marlon Brando, and 6,000 T-shirts of Pacino as Scarface.

INDIANA: What did you think about Andy’s films?

WORONOV: I didn’t really think about them, but last year I was forced to. I’ll make a picture for you. Okay. It’s freezing in New York. I’m staying at the Gershwin, a Midtown hotel straight out of Raymond Chandler. They are having a Warhol festival, everyone gets a free silver wig and a pair of Wayfarer sunglasses. All week, there are two to three of Andy’s early black-and-white films running 24/7 on the lobby walls. It’s 2 A.M. and on the wall beside me is the Empire State Building. I want to go to bed, but instead, I sit down, and my brain floods with feelings about the past when Daddy took us to the top of the tallest building in the world, about America, my tragic country that was great but is not great anymore, and about the city I can no longer afford to live in. All this takes about three seconds because I promised myself a long time ago I would never cry in a hotel lobby. But the building continues to demand my attention. And, unlike a painting, it is not dead. It’s living, like a window that sees only the past. “This is brilliant,” I blurt out, and four different people tell me to shut the fuck up. But my brain is bubbling over. I realize that Andy never meant to do a film. He was doing a painting. Pop art put the image back in painting, and Andy took it even further and put the image on film instead of canvas. He wasn’t directing, he was painting. It’s only taken me 40 years to realize that these films were never meant to screen in a theater, where I thought they were boring. They were meant to hang on a wall. They are Andy’s greatest paintings. When I see the young me on the screen, she is a stranger — she’s not really sure of where she is but the audience understands that she is their mirror. I’m not acting, but I’m not being myself either. It’s a performance piece. Andy decided to put it on his canvas of film in an effort to stretch the boundaries of perception. It’s a relatively simple progression except that film is not simple. It fucks with time, promises immortality, and delivers her evil twin, fame . . . an ugly little animal with a huge appetite.