Dana Spiotta’s Age of Innocence

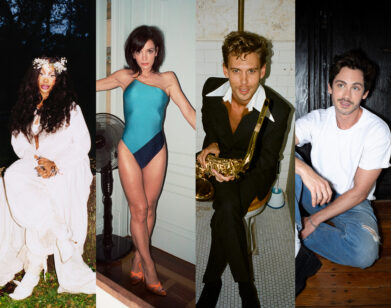

ABOVE: DANA SPIOTTA

Dana Spiotta is a writer’s writer. A professor at Syracuse University in the MFA Program, the L.A.-native pens strange, intimate, off-kilter tales of marginalized characters often dealing with their own quiet devastation. Through spare and striking prose Spiotta has managed to create fascinating worlds in her four novels, including the National Book Award finalist Eat The Document (2006).

Now 50, Spiotta’s latest work, Innocents and Others (Scribner), follows Meadow and Carrie, two filmmaker best friends who grew up together in L.A. in the 1980s. While Meadow moves to upstate New York to make art house documentaries, Carrie achieves mainstream success in LA.

One of the subjects of Meadow’s documentaries is Jelly, a mysterious woman who also goes by the names Amy and Nicole. Jelly’s speciality is a slow-burn phone seduction of famous Hollywood celebrities—none of whom she meets in person.

Alienation, narcissism and deceit are constant themes in Spiotta’s work and they abound in droves in Meadow and Jelly. But, while Spiotta’s protagonists may not evoke warmth or empathy, the author keeps her plot turning with unexpected twists, pulling the reader further into the closed and curious worlds of the characters.

JEFF VASISHTA: What makes you decide that the kernel of an idea can be elaborated into a novel? All your work is earmarked by its uniqueness—is that a pre-requisite?

DANA SPIOTTA: I am always trying to do something new and different. The first step is curiosity, questions. You pay attention to what fascinates you. If you can’t shake it, there is something there. The reaching and the discovering give the novel its energy. We all know there has to be something at stake for the characters for the novel to come alive. But there also has to be something at stake for the writer. The writer has to take risks and go somewhere full of mystery and possibility for the novel to deepen over the years it takes to write it. The writer has to be brave, I think. I want it to surprise me just as I want it to surprise the reader. Both writer and reader need to be gripped by it. I want what I write to be deeply engaging and strange and true. All of those things.

VASISHTA: Where did the Jelly/Nicole, Meadow, and Carrie characters come from?

SPIOTTA: Nicole was inspired by a woman—Miranda—who is infamous for catfishing Hollywood men in the 1980s. I thought it was fascinating because it connects to the present and how people pretend to be someone they are not on the internet. When I heard about her, I wondered, why did she do it? What was the endgame? Because eventually the person wants to see you and will discover it is a fantasy. A person catfishes for what? The attention? The love? The feeling of power? I had those questions, and for me, questions lead to imagination and fiction. I connected her to blindness and phone phreaking. I put her in Syracuse and made her familiar to me and my own experience of wanting attention, wanting love, wanting power. Don’t we all want that?

I grew up in 1980s and went to a school like the one Meadow and Carrie go to. So they have elements of me in them. As does Jack and even Oz. Deke too. But as Meadow would put it, they are mostly invented, which is to say, wholly invented. When I write characters, I need to hear their voice. As soon as I get them speaking, and I feel how they use language, I understand who they are and what they want. Usually there is a paradox in what a character wants. A conflict is built deeply within them. And then you put them in motion, throw everything at them until they reveal themselves further. You are always working towards the moments in which characters experience reckonings or insight or change. I like to track them past those moments. Years past, and trace the consequences as the days stretch into years in a life. For example, I always loved how in Middlemarch you see how poor Lydgate is making a huge—but human—mistake. The novel traces its consequence with such precision. And then we jump ahead and get to see that mistake as it stretches out over his life. That kind of tracking of a life is what the novel is really good at. Showing how mistakes affect us over time.

VASISHTA: I like the way you meld fact with fiction. Here, Jelly is based on Miranda and there’s an Orson Welles-type filmmaker who may or may not be him. You did that as well in Eat The Document and the Beach Boys.

SPIOTTA: I like to mix the real and the imaginary. Sometimes it is characters inspired by real people I know or know of. Sometimes it is a named person from the common cultural dreamscape. And it is tricky, because they have a lot of associated ideas that come with them, and a lot of actual facts. But of course, I try to be very upfront about reimagining them. I take the outline from a real person as inspiration, but the in-line is totally made up. Which is why I usually invent imaginary names for these characters too. Orson is named, but he is not even the real Orson in the world of the novel. He is a fantasy of Meadow’s. In any case, I am turning them into characters for the purpose of my book. In the book, Meadow talks about “fabules,” which is her name for story telling, a “wishstory,” “half dream and half fact” and she clarifies that stories have “elements both stolen and invented—which is to say, invented.” As soon as you put a “real” person in a book of fiction, they become a fictional character. Since this is a book interested in the way we construct truth, it comes up again and again. Even a documentary portrait of a person that tries to be very accurate is shaped by the filmmaker in so many ways. Even if we try to see people in our lives accurately, it is distorted by our own wants and prejudices and experiences.

VASISHTA: Deceit plays a big role in your novels. Do you find it’s a good concept around which to structure a story?

SPIOTTA: I am, it seems, interested in people with multiple identities. I think we all have multiple identities. I am one Dana when I am talking to my daughter, another when I am talking to the IRS, and another still when I do an interview. These characters are just extreme versions of ordinary human self-switching. Jelly is different from previous characters because she is really a kind of confidence artist. She is fabricating a lie, but doing it as a collaboration with the other person she is seducing. The problem is, of course, that the other person doesn’t know he is collaborating in a kind of play with her. So when it goes father than she expects, it does become a deception that is quite damaging to all.

VASISHTA: Guilt seems to be another theme. Would it be fair to say Meadow is plagued by guilt, which is why she does what she does?

SPIOTTA: Yes, I find poignancy in the moments when a person realizes that she has made mistakes. I am not as interested in the mistakes themselves as I am with the consequences and how the person responds to her realization. Does she try and change? I wonder if a person can change, or is it enough just to try? Or maybe just to see what you have done, truly, with no rationalizations, as Sarah does, is enough. At one point, Meadow says that she doesn’t mind if she is a bad person, but she would hate not to know it. She makes documentaries about people who have done terrible things—and she tries to implicate her audience in their behavior. Which is something I think about in fiction. She tries to make these things complicated and fraught, which they usually are. But the big moment comes when she realizes the person she has become and how she has hurt other people. The irony is that she tries so hard to see other people and to show her audience other people, but she is blind to herself. We are all like that. We are designed to make breakfast and get on with our lives. We distract ourselves, we blame others, we keep moving. But questions will leak in sometimes, and we might wonder if we are good, and how to be good. And what do we do with the answers? I was very interested in Larissa MacFarquhar’s book Strangers Drowning about extreme do-gooders. Why, really, should any of us have anything extra when there are people without nearly enough? Is there a morally coherent answer to that?

VASISHTA: How does teaching inform your writing? Do you find that they are two completely different parts of the brain or do you need to unplug from the classroom in order to create?

SPIOTTA: I think most writers have to have a practice of writing. For me it is very early in the morning. I try to make it a separate world from the rest of my life. There has to be a bright, hard line around it. So yes, my teaching exists in a different part of my brain. However, I am lucky enough to teach very smart graduate students. We close read interesting books and discuss them, and this makes us all become better readers and writers. Also my teaching forces me to articulate what I think works in a piece of fiction and how I think it works. All of that gives me energy as a writer.

INNOCENTS AND OTHERS IS OUT NOW.