Dan Chaon’s Conspiracy Theories

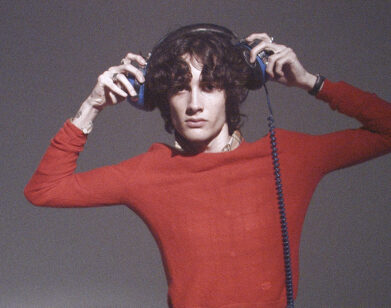

ABOVE: DAN CHAON. PHOTO COURTESY OF ULF ANDERSEN.

It’s strange to discover that some of your creepiest fascinations and deeply private fears have, by chance, become the key ingredients of a novel. It’s like recognizing yourself in a fictional character—except it’s less a character than a dark psychological haunting that rises from the back of your brain in the small hours of the night. But if any writer consistently manages to crawl into those hidden regions of the mind and return with our terrors on the page it’s the great Dan Chaon. Time and again, he’s brought our demons out in the sun to play, and perhaps what’s so disturbing about his work—and what makes it so irresistible—is that it isn’t the stuff of a sensationalist with a few convincing shock tactics. Chaon is such a gifted, experimental prose stylist with such a fine understanding of the compulsions and desires that drive a human being, the farther we get into his very weird stories, the more they start to seem almost perfectly normal. It’s not so much who is wrong or what is wrong or even why-all of those states are a given in a Chaon universe—but how?

Take his latest novel (and perhaps his best), Ill Will (Ballantine), which is a clash of crimes and pattern fixations. As a child in Western Nebraska, Dustin Tillman was or was not witness to the spree murder of nearly his entire family (mother, father, uncle, and aunt); the murders were pinned on his adopted older brother, Rusty, a definitely troubled and questionably Satanic-worshipping teen who received a life sentence. Flash to the present, and Dustin is a middle-aged psychologist in Cleveland, Ohio; he’s recently widowed, raising two boys of his own, still suffering temporarily flashbacks of his parents’ deaths, and soon learns that Rusty has been released from prison due to DNA testing that proved his innocence. Instead of solving an old personal crime or attempts at a bittersweet reunion (or really even dealing with his own bereavement or his son’s increasingly debilitating heroin addiction), Dustin becomes obsessed with a hypothetical serial killer attacking young college-aged men who periodically vanish from Midwestern bars and end up drowned in nearby rivers. As the novel progresses, the characters, the stories, the actions, and the reenactments begin to bleed into one. It becomes increasingly difficult to determine which side of a Chaon character is in control: the side that wants to survive or the side bent on self-destruction.

Chaon was raised in Nebraska but has lived most of his adult life in Cleveland where he teaches at Oberlin College. I, too, hail from Ohio (Cincinnati). On top of that admittedly minor commonality, I have also followed (late at night, on my phone, due to bouts of insomnia) the many, many real-life conspiracy theories of a serial killer or cult that is responsible for a tragic number of drowning deaths in recent years all involving young white men going missing after a night out drinking and ending up days later found in nearby bodies of water. I wondered if this mutual fixation might be Ohio-related, a sort of Midwestern madness showing through.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: I’m from Ohio. I know you’re not originally from Ohio but….

DAN CHAON: I almost feel like I’m from Ohio at this point. I’ve been here a long time, since 1990.

BOLLEN: Much of your new novel takes place in Ohio, particularly around Cleveland. I’m wondering, is there such a thing as an Ohio story, or an Ohio mood, or even the question of can you be an Ohio writer? There are Maine writers, Florida writers, Texas writers, California writers. What about Ohio writers?

CHAON: I don’t think Ohio is really a state. I think it’s a series of duchies. There’s Cincinnati, there’s Toledo, there’s Cleveland, etcetera, and they don’t get along. I think this is a Cleveland novel. The mood of winter in Cleveland was definitely an energy I was drawing on, just to bring everybody down.

BOLLEN: [laughs] There is a very dark feel to your winter in Cleveland. I think the Cincinnati winters are less brutal.

CHAON: There’s a kind of grayness that sucks the vitamin D right out of your body. It’s been a little weird this winter because we’ve hardly had any snow. But, most of the time, it’s pretty brutal.

BOLLEN: There’s a contrast of seasons in the book.

CHAON: Yeah. The main action in the present tense takes place in the winter, and the main action in the past takes place in high mid-summer.

BOLLEN: Your descriptions of summer are so good too, that feeling of sweat and lethargy and sleeping in a trailer. Summer always feels a little insane.

CHAON: Yeah, and because it’s Satan, I wanted to have the solstices in there. There are a couple of things that happen in spring and fall, but I chose the seasons on purpose, for sure.

BOLLEN: You also needed the brutal winter for cold, icy rivers that young men fall into. One thing that blew me away while reading Ill Will was your inclusion of an active urban legend or a conspiracy theory that I don’t think most people even know about. But I do. I don’t think I’ve ever mentioned this aloud to anyone, but I have insomnia, and for a year, I routinely kept going to a blog called “Footprints at the River’s Edge.” Do you know that website?

CHAON: Oh, yeah.

BOLLEN: I spent hours in the middle of the night reading about missing young men in America on that blog. I should basically be a character in your book.

CHAON: [laughs] You are not one of them!

BOLLEN: How did you even stumble upon this theory that someone is kidnapping young men and discarding their bodies in nearby rivers? I guess the Smiley Face Killer theory did garner a lot of attention at a certain point….

CHAON: Well, actually, I have a kind of half-assed personal connection to this because my brother-in-law was going to school in Wisconsin during that period and one of his friends was one of the kids that drowned. He was the first one to key me in to the story. Because a lot of people really strongly believed that it was at the hand of a serial killer.

BOLLEN: Is that the guy who disappeared wearing the Native American costume?

CHAON: Yes, it was.

BOLLEN: Oh my gosh! And your brother-in-law also thought it was a serial killer?

CHAON: Yes, he really thought it was a serial killer.

BOLLEN: What do you think?

CHAON: I can’t find the logic in it. The only thing I can think is what the character Aqil says toward the end. That it’s a roller coaster ride that people notice and want to go on. It turned into something by first becoming an urban legend. I do think some of them are actual killings, but I don’t think there’s a serial killer.

BOLLEN: Do you believe there’s a connection between the smiley faces found near the bodies?

CHAON: That doesn’t make any sense. I’ve watched that documentary about it a bunch of times, and I can’t quite buy this. I’ll look out my window and see a smiley face.

BOLLEN: Were the two New York detectives that promoted the smiley face theory the inspiration for Aqil and Dustin?

CHAON: I didn’t want my characters to have the amount of experience that those guys had. I wanted my people to be a little more in the armchair-detective category.

BOLLEN: How does this odd urban legend become fertile material for your fiction?

CHAON: I had notes about it for a long time. I just couldn’t figure out how I was going to use it. First of all I didn’t want to write a college novel. I didn’t want to have the setting be a college because, as they say, don’t shit where you eat. So I couldn’t figure out how to use it. I was working on this other thing, about this brother being released from the Innocence Project, and somehow those two ideas felt connected in a weird way. I just tried putting them side-by-side to see what happens.

BOLLEN: When you put something “side by side,” do you mean that you conceptually play with the pairing in your head? Or do you mean you actually start writing them as one work to see how they mix?

CHAON: I start writing. A lot of my work is collage. I’m working with fragments a lot of the time and the connective tissue isn’t there yet. I think of it the way comics work. You have a block here and a block here, and there’s this white space in between. Somehow your mind makes the leap to connect those two blocks. Finding a way to trick your mind into connecting those blocks is one of the fun things for me about writing. You can have those leaps that will emerge into something, if you’re lucky.

BOLLEN: I’ve always thought that the act of writing is very similar to the way conspiracists weave a conspiracy theory—they invent and they build and they make the unbelievable start to sound believable. They find patterns and connect pieces.

CHAON: Oh, yeah! And at the same time it’s something we all do. We’re on public transport and you see a lady and wonder where could she be going, and suddenly you have all these crazy things that you’ve imagined as you’re sitting there. It’s a kind of heightened daydreaming that also has a sense of urgency behind it. I suspect psychics do the same thing. But I’m surprised you know about that urban legend. I didn’t know it was something a lot of people had heard of.

BOLLEN: Well, what’s so intriguing about it, and your novel really gets to the heart of this, is that it’s a conspiracy about some cult or killer targeting young middle-class white collegiate men. Of anyone in the American population, that demographic would seem the most invulnerable. If there is a presumably safe or protected group in America, it’s young white men. That’s what makes it so uncomfortable and strange. I suppose it’s also like the heroin epidemic in whom it targets—which is another element of Ill Will. Were you interested in that idea of something that was after such an unlikely set of victims?

CHAON: One of the things I noticed was that a lot of the response to the deaths was a kind of amusement. There wasn’t a lot of sympathy for these kids that drowned. That thing in the book about the serial killer’s name is Darwin, I heard that. I’ve seen that in comments sections over and over again. There are people who are kind of delighted, and that’s creepy to me. I was somebody who was bullied by jocks in high school and there is that thought, “Yeah, it’s time for you guys to get yours,” but at the same time, they’re not asking to be killed. They have loved ones and so on. I don’t know. There are all kinds of strange threads in American culture, and places where sympathy is extended and places where it isn’t, and places where outrage is extended and places where it’s not. It’s this constantly shifting barrel of eels.

BOLLEN: Then you have Dustin’s brother, who is a young white man who becomes a scapegoat for a series of family murders. So in a way, it’s another attack on this group.

CHAON: I think the hostility there is a different, because it’s very class-centric. You know, the biggest indicator of where you live is your income. If you live in this suburb you make this much money, and if you live in that suburb, you make that much money, and if you don’t have any money you live where you’re allowed to live.

BOLLEN: Certainly the hysteria of teen Satanic worship in the 1980s definitely had a strong element of class anxiety to it.

CHAON: Yeah, it was always the working class druggie kids who were the ones that were going to kill your baby.

BOLLEN: The ones that you couldn’t control, the delinquents, the ones whose parents you couldn’t trust to watch over them. They were the ones worshipping Satan in the parks around the local supermarket.

CHAON: In Nebraska where I grew up, and I’m guessing probably in Ohio as well, a lot of the Satan stuff was going from the churches. They were really convinced about Satan worshipping. I remember there was a police task force in my tiny town in Nebraska. Somebody knocked over some gravestones or something and that was considered potential satanic activity. But people forget it was a real thing.

BOLLEN: You were saying earlier about how your writing is similar to connecting fragments. There are sections of Ill Will where there are four separate narratives playing out simultaneously on one page. These separate columns run on for several pages, but if you read one page at a time, like I did, it creates this really trippy effect of one plot superimposing itself over another. It’s done beautifully but it is also a risky move as a writer. How did you orchestrate that?

CHAON: It started out as a free write that I was doing, based on a exercise I give my students where I want them to use boxes to contain a scene. I started using it myself and I got really attached to it. When I showed it to my editor, she was like, “Hmm… I don’t know if people will get what you’re doing here.” We started arguing back and forth and I think she finally came around to it because it really got at the feeling of dissociation. It sort of did to the reader what I wanted.

BOLLEN: You’re one of the few writers working today who are willing to go to the dark side in your work. I feel like Dennis Cooper is another example, but he has a very different vibe—

CHAON: I’m not quite as transgressive.

BOLLEN: Well, I wanted to ask what that’s like for you to go far over into the dark. Do you ever feel you’ve gone too far? Does a scene every get too bleak for you? What’s your inclination to go there?

CHAON: I think I’ve always tended to find that element fascinating. I’ve always been a horror movie fan, since I was a kid. And I was also a really scared kid. I was easily scared of the dark. One of the ways I would try and get away from my fear of the dark was to pretend like the monsters were my friends. I’ve always felt like that kind of stuff is catnip to me and avoiding it is trying to stay within the realm of good taste. I have enough people around me that are readers that will say, “No, don’t do that.”

BOLLEN: So you’ve been censored by friends who think you’ve gone too far?

CHAON: Yeah. I also have just my own limits about stuff. I’m not interested in writing graphically about sexual assault for example. I feel like the stuff that I’m fascinated by is the stuff that’s part of the public imagination of what horror is. The bleakness is a different issue. I think that just stems from my personality. I wish that I offered a little more glimmer of hope sometimes. And there’s this weird part of me that’s like, “Oh, ha-ha, I’m going to go as far into that as I possibly can.” For me, there’s something satisfying about the bleakness and the horror because it makes you feel like, “Okay, I’ve seen what that’s like and now I can come up for air and I’m safer.”

BOLLEN: I too was a deeply frightened kid obsessed with horror films. I’m curious, were you monster friends more like Jason Voorhees or were they werewolves? Who were the ones you most feared?

CHAON: Well, I grew up in the time of the big serial killers. [John Wayne] Gacy was one of the people I was really afraid of. The clown. And Michael Myers and Jason too, although Jason wasn’t that scary to me. Michael Myers was much scarier. The first Texas Chainsaw Massacre was really scary. The Hills Have Eyes was really scary. The ones that I thought were the most frightening were the ones that were kind of precursors to the movie Get Out, where it’s people you’re supposed to trust who are completely out to get you. Like Rosemary’s Baby or Harvest Home. You don’t know, but everybody’s plotting against you.

BOLLEN: I think your literary bona fides are pretty set, but in general do you feel that not enough respect has been given to horror or the dark thriller in the literary world?

CHAON: Many of the books and films that are important to me are in that genre and it’s something I have a lot of respect for. I think it’s something that has been in flux in the literary world for a long time. There was a period where certain writers were just not going to get a National Book Award nomination for writing something of that ilk. But I think that’s changed. I think that for all intents and purposes [Colson Whitehead’s] The Underground Railroad is a genre novel. Then you go back to the Shirley Jackson novel The Haunting of Hill House, which was a National Book Award nominee. There are periods where the gatekeepers have this idea that only domestic realism counts, and then that sort of lifts a little bit. Maybe the one exception is the Oscars; I don’t think they’re ever really been that open to horror. I think some of the really great American films over the past five or ten years have been horror movies. I don’t know if you saw this but It Follows…

BOLLEN: Yes! I loved it!

CHAON: The mood and texture were beautiful.

BOLLEN: And it was a horror where the teenagers weren’t dumb. They didn’t read as dumb L.A. actors with questionable stylists. There was a beautiful authenticity to those actors and the lives they portrayed. So many horrors really cheapen the cultural understanding of a teenager.

CHAON: I agree, but I think that’s how it’s always been with a few exceptions. I still think that Jamie Lee Curtis’ performance in Halloween was a really astonishing young performance. Then you look at whoever gets killed in the Friday the 13th movies, and none of them really stick in my mind.

BOLLEN: Friday the 13th really only comes alive in the last ten minutes. The chase scene with the final girl is usually pretty thrilling. Other than that, it’s a rather lugubrious body count.

CHAON: I guess one of the questions for me is what counts as horror and what doesn’t? And what counts as literary and what doesn’t? There’s so much grey area. I think most of Cormac McCarthy’s stuff is horror straight up. And certainly there are people like Kelly Link and Karen Joy Fowler and a whole group who are writing in a certain genre but have plenty of literary respect as well.

BOLLEN: I find Patricia Highsmith a comforting model. She wasn’t even being published in the United States at the time of her death. Her books were out of print. But she’s had a resurrection and a new appreciation in the last decade or so.

CHAON: Yeah, and the same thing with Shirley Jackson, who is starting to get a reevaluation just recently with the publication of that biography.

BOLLEN: Did the horror films of your youth lead you into writing fiction? Was that the trigger?

CHAON: I wrote as a kid. I’ve always been a writer, even early on. I had this correspondence with Ray Bradbury when I was like thirteen, and he was just so kind and so encouraging. But I was also super obsessed with film, and when I went into college, I started in the film department. I really thought I was going to be Alfred Hitchcock or Orson Welles or something. This is what we all think.

BOLLEN: Or at least a Tobe Hooper.

CHAON: At least! But then the thing that made me turn more towards writing was realizing how hard it was going to be to get a singular vision on film and how much more control I would have if I were writing novels.

BOLLEN: I usually forego the question about writer’s writing practices, but in your fragmentary style, I do wonder, when do you know a book is coming together? Or is it a case of the glue drying in the edit process?

CHAON: One of the things that I’ve started with here is trying to write a chapter every night.

BOLLEN: Oh, you’re a night writer.

CHAON: I’d try to write from the beginning to the end of the chapter, and I would do these things where the chapter ended before I had actually finished the sentence. Then I went back the next day and I thought. I like that.

BOLLEN: So many sentences are left unfinished. In Dustin’s brain and mouth especially.

CHAON: Yeah, and that just started out from the idea that I’m going to try and write this chapter in one night and I’m not going to look at it and just move onto the next chapter. I had all these tiny chapters that were almost like flash fiction or prose poems. Then when I started to put them together I realized I liked the rhythm of these short chapters and this free-floating quality. That actually helped me to figure out how I wanted to put the book together.

BOLLEN: What about the need to resolve a story? Any time you introduce a dead body or a murder or a mysterious death, there’s pressure to answer the big, looming question. Did you figure out the answer to that question on page 50 or where you still connecting the dots as you wrote the final chapters?

CHAON: I never figure things out until usually well after everybody else has. I’m still kind of unsure what’s going to happen. The other thing is, I have a much higher tolerance for ambiguity than other people do. I’m happy when stories don’t tell me everything at the end. But I also have an editor who’s like, “You want people to read the book, so there are questions that have to be answered in order for them not to throw the book onto a fire.”

BOLLEN: I also feel like the ambiguity card has sort of played itself out. It’s become a gimmicky posture of literature: “I won’t solve this mystery for you. I will ruminate instead on how most of life refuses clear answers.” It’s become it’s own sort of easy way out.

CHAON: I think at a certain point the book develops a certain weight, or pressure. You’ve been pushing the rock up the hill for a long time and then it starts to roll and things do start to come together in the last two thirds. I got into the world of the story really fast. I already knew the characters. I didn’t have to think about what they would do. It was like you’ve been acting in this play for this amount of time—you just know how to put on the clothes and you know what the characters would do, so things start to emerge and come together a lot more quickly. Not to say there weren’t a few dark nights of the soul when I thought, “I will never finish this.”

BOLLEN: But did you have an inkling that some of these characters might not live to see the last page of the book? There is some ambiguity in your ending.

CHAON: No, I did not know that. But my sons were reading this as I was going along. They’re both in their 20s.

BOLLEN: What was their reaction?

CHAON: At one point early on, I told them I was writing a story about a widower and his two sons, and my youngest goes, “I know you’re going to kill me, aren’t you?” And I went, “No, of course not!” And then I thought, “Well maybe I am!”

ILL WILL IS OUT NOW. CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IS INTERVIEW’S EDITOR AT LARGE. HIS THIRD NOVEL, THE DESTROYERS (HARPER COLLINS), COMES OUT JUNE 27, 2017.