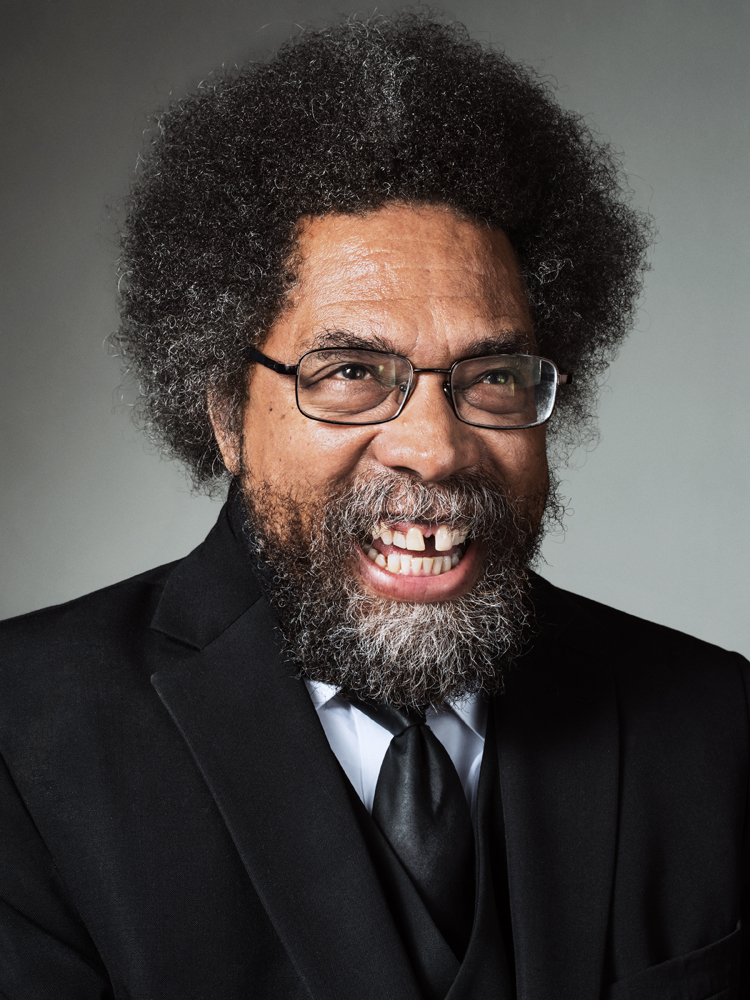

Cornel West

I always felt called to serve . . . teaching, truth-telling, bearing witness, and being willing to live and die for something bigger than yourself. Cornel West

Many years ago, before he was a familiar presence on television, film, and radio, before he dropped his Reader in 1999—a decades-spanning collection of his passionate, polymathic essays—and was recognized, rightly, as one of the most dynamic public intellectuals in America, some people couldn’t get a grip on Cornel West. “ ‘What are you?’ they asked me,” West says now. “And I’d go, ‘I’m a jazzman in the life of the mind. I’m a bluesman in the world of ideas. I’m a participant.’ ”

Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1953, and raised mostly in Sacramento, West first started participating in academia at Harvard, graduating magna cum laude in Near Eastern languages and civilizations, and then becoming the first African American to gain a PhD in philosophy from Princeton University. From there, West began weaving together the neopragmatism he’d been studying with the theological tradition of his childhood in Shiloh Baptist Church, the existentialist yearning of his great heroes Chekhov and John Coltrane, and the transcendentalism and romance of his favorite poets and soul musicians, to build a kind of unified theory of belief and action. As a professor of African-American studies, at institutions including both Harvard and Princeton, where he is still a professor emeritus, Dr. West’s teachings were never of the cripplingly abstract variety you remember from your Philosophy 101 class, but instead pragmatic, engaging, and uplifting—it is not for nothing that his demeanor and oratory style is often compared to that of a Baptist minister.

His writing—as well as his speaking, and sometimes rapping (in the case of his 2001 spoken-word album Sketches of My Culture)—displays a broad fluency in the American vernacular, pulling from a library of inspiration that stacks Duke Ellington beside Toni Morrison beside W.E.B. Du Bois. And these days, post-Ferguson, at the tail end of Barack Obama’s presidency, there may be no more poignant voice on the way we live now and the way we might live tomorrow. Of Obama, Dr. West was an early supporter, but is now increasingly critical, calling the president “counterfeit,” with the disappointed heartache of a friend betrayed.

Dr. West, now 61, has, in the past, described himself as a revolutionary Christian in the Tolstoyan mode, one who wrestles with his faith on a daily basis. So his questioning, and fault finding, is not directed solely at the president, or at Al Sharpton, whom he’s described as an apologist for the administration, but also at himself, at the entire class of grassroots leadership in America, black and white, and at his role within it. His new book, Black Prophetic Fire, his 21st, out now from Beacon, follows the form of his best-known books, Race Matters and Democracy Matters, in weaving together his many musical, philosophical, and political ideas and influences with great pathos and verve in order to call for a kind of awakening, a new dawn of activism and responsibility, and a new way, even, of finding fulfillment—what he calls “living in the blues idiom,” to find compassion in the midst of catastrophe.

One evening this past September, Dr. West’s friend, the incredibly prolific producer, late-night bandleader, author, and drummer of the Roots, Ahmir Thompson, better known as Questlove, sat in on the professor’s class at Union Theological Seminary in New York while they were discussing Du Bois and the prophetic tradition of African-American leadership. After class, they moved to Dr. West’s book-lined office for a chat about revolution, getting involved, and the rising price of soul food. —Chris Wallace

QUESTLOVE: So you were teaching your class about the difference in social impact between Marcus Garvey and Du Bois. And what I took away was the question of whether we need a messiah figure to lead society, or can it be truly grassroots? I also wonder what good it will do today. Chuck D taught me a long time ago to aim really small. And everyone now has [Michael] Jordan-itis—everyone wants the star position. So where do you fall, on the question of how we can best move forward as a society, between the Moses-messiah figure, like Martin Luther King Jr. or, say, Occupy Wall Street, which really didn’t have a leader?

CORNEL WEST: I take my fundamental cue from John Coltrane that says there must be a priority of integrity, honesty, decency, and mastery of craft. I take my second cue from [organizer and activist] Ella Baker that says, with that integrity, honesty, decency, master of craft, there must be an attempt to find, among everyday people, vision, voice, and modes of organizing and mobilizing that does not result in the messianic model, in the HNIC, the head negro in charge. This is where Martin King comes in, and the distinction we made in class between conspicuous charisma and service-oriented charisma. It’s possible to be highly charismatic the way John Coltrane was, and still de-center oneself, as he did, to allow for McCoy, and Elvin, and Reggie, and the others [who played with Coltrane] to lift their voices with tremendous power. Martin, at his best, was able to empower others, galvanize others and, through an integrity and humility, recognize he’s just another human being, not a messiah. At his worst, he was the Moses that everybody had to defer to.

QUESTLOVE: So that’s a dangerous thing, in your eyes.

WEST: Yes! If you take the focus away from integrity, honesty, decency, and look only to the messianic figure, then he will manipulate you, she will manipulate you—it tends to be men more often than women because this is a patriarchal model. Now, I’m not talking so much about brother Obama right now; I’m talking about grassroots movements. But when you have a U.S. president, only one wins the election. And there’s no doubt that he was better than the right-wing candidates. But then the question is whether we have the courage to keep him accountable.

QUESTLOVE: So you hold him to the same standards, even in the face of his obstacles?

WEST: [laughs] There has certainly been ugly, right-wing hatred targeting Barack Obama. But when it comes to the three central issues—Wall Street, drones, and national surveillance—the right wing didn’t push him into [his positions]. He chose each one of those. He brought in [former president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank] Tim Geithner [to be Secretary of the Treasury]: Wall Street. He chose drones—he and Hillary chose drones, as opposed to ensuring that innocent civilians, especially babies, are not killed. And he chose national surveillance, using the Espionage Act against Snowden, among other things. And not focusing on the new Jim Crow, the prison system, the way in which he should have, he chose that, too.

QUESTLOVE: So let me start at the beginning. I grew up in Philadelphia, son of a doo-wop singer. What was your upbringing like in the ’50s?

WEST: I was born in the same hospital as [the Gap Band’s] Charlie Wilson. Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma, the black Wall Street. I only stayed a few weeks, then we left to Topeka, Kansas, stayed there for a few years, then left for Sacramento. So I’m basically a West Coast brother. I’m Sly Stone, Tower of Power …

QUESTLOVE: You and I connected through our discussions of music. This room, adorned with the greatest literature ever, and records—this was my life, my room full of documents, growing up. Music saved me. How did music influence your life at an early age?

WEST: I remember that section [in Mo’ Meta Blues] about Prince records—”Here’s another one, here’s another one.” [laughs] For me, music is in no way ornamental or decorative; it is constitutive of who I am. It began in church, Shiloh Baptist Church, the Silver Echoes, the Senior Choir. Sly Stone was a member of the [Northern California] Mass Choir. Sylvester Stewart [Sly Stone’s real name] from Vallejo used to play a little bit of organ in our church, just letting it out. From the very beginning, it was clear to me that a musical mode of being in the world was the most desirable way of being in the world—trying to be melodic, but also having the dissonance. So by the time we moved into slow dancing in the garages—and this was probably a little bit different than your generation, because I’m older-school than you—it was Curtis Mayfield, but it was also the Delfonics, the Dramatics, the Emotions, the Whatnauts’ “I’ll Erase Away Your Pain,” it was the Manhattans. It was smooth. It was groups with a variety of voices harmonizing together. Whereas, I think, for the next generation, it was harder for those kind of soulful groups to have the impact.

QUESTLOVE: My theory is that once the VCR age took hold, around ’83, ’84, you have a generation that only liked the highlights and celebrated individualism. You fast-forwarded the tape to see what Michael Jordan did. You rewound that “Billie Jean” performance on Motown 25. Plus, it’s easier for labels to deal with just one person. So the idea of community—right now the Roots are defiantly together. Even if we wanted to break up, we know the historical consequences of us no longer existing.

WEST: The last hip-hop band.

QUESTLOVE: We’re almost the last hip-hop group with a major record deal. Everyone is a solo artist now. I mean, technically, yes, if OutKast were to record again … But right now we’re the last black band with a major-label deal.

WEST: Wow.

QUESTLOVE: We’re an endangered species. And I would like to teach people that Jordan didn’t win those rings on his own.

WEST: [laughs] You make the point in your book that the drum machine can’t speed up or slow down [to accommodate] the improvisational, on-the-spot shift. The great Bootsy Collins—towering figure, genius in so many ways—he and I were recording [Collins’s 2011 album] Tha Funk Capital of the World, and one of the great moments, for me, was to see brother Clyde Stubblefield’s drum sticks that he had given to Bootsy. When I touched them, I shouted because the level of craft, technique, sophisticated usage, soul, timing, and listening in those sticks is easily lost in a machine. And you talk about your foundation: [John “Jabo”] Starks, Stubblefield. Those two are the funkiest drummers in the history of popular music. Without that human capacity for creativity, improvisation, and variation, what’s missing—and this is what is the saddest thing about contemporary culture—is that, when you hear the voice of a David Ruffin, you hear a depth of tenderness and sweetness along with roughness and toughness. And once you no longer have that kind of music touching the souls of young folk, but just have the noise stimulating their bodies, it’s going to be hard to produce people of deep courage and vision and integrity. They think life is just instant gratification, short-term gain, and celebrity status, rather than the process of becoming the best.

QUESTLOVE: Destination versus the journey.

WEST: Absolutely! The whole process of Coltrane’s formation is part and parcel of where he ends up—and where he ends up is continually calling himself into question.

QUESTLOVE: For lack of a better word, is spirituality missing?

WEST: Yes.

QUESTLOVE: Okay, if you look at every “black” singer, beginning with, say, Ma Rainey and ending with Ariana Grande …

WEST: Who my daughter’s crazy about.

QUESTLOVE: You have Mahalia Jackson, who begat Aretha [Franklin], who then begat Chaka [Khan], who then begat Whitney [Houston] and Mariah [Carey], who then begat the mall generation—Christina Aguilera, Beyoncé. A singer like Rihanna, for instance, doesn’t have a gospel background. She’s more in line with, say, Madonna. And I’m noticing that singers today—especially with the embracing of Auto-Tune—are taking the human feel out of music. The spiritual level, a lot of which came as a result of the civil rights period, is missing. That period had to happen, and their idea then was that they were going to make it better for our generation 40 years on. Well, here it is 40 years later, and progress has been more or less two steps forward and two steps backwards.

WEST: [laughs] Yes. But you’ve got to remember, Billie Holiday wasn’t gospel-based in terms of church, the way Sarah Vaughan was, but the passion, the pain, and the transfiguration of the pain into the most subtle sound and sophisticated voicing came from Billie Holiday. I think what’s missing these days is that the market requires quick affectation rather than a deeper passion. You’ve got Anthony Hamilton out there, Jill Scott, Angie Stone, Kim Burrell—we have some folk who can take you there. But the market does not allow them to surface at all. I’ll give you a good example. In the 1960s, a brother named Rudy Ray Moore came up, and alongside him you’ve got Curtis, Jerry Butler—all these towering artists who have some visibility. What if Rudy Ray Moore of Dolemite [1975] were the public face of black culture? And Curtis Mayfield and all the others were in the background? We’ve got a number of young folk—not just black folk, because being soulful is something that cuts across the border; Eminem is a serious artist in a black form, the same way that Artie Shaw was—you listen to “Nightmare” by Artie Shaw, you say, whoa. You listen to Harold Arlen’s “Over the Rainbow,” you say, “This is a Jewish brother from Buffalo and he’s got some soul.” Ethel Waters said, “He’s the negro-est white man I’ve ever seen.” So soulfulness is open to the world, if they’re willing to dig deep inside of the dark precincts of their soul and allow that voice, not just an echo, to come forward. That’s what’s missing. And, in a way, it produces a kind of spiritual malnutrition, moral constipation—more and more emptiness of the soul. Even if you know what’s right, you don’t have what it takes to execute it. You can’t get it out. What comes out is market, market, market, short-term pleasure, pleasure, pleasure, money, money, money, status, status, status. If you view life as a gold rush, you’re going to end up worshiping a golden calf. And when you call for help and that golden calf can’t respond, you go under.

QUESTLOVE: Was your passion for academia and education a life-long thing?

WEST: They’re always on the continuum. My mother—thank God, she’s still alive—was a principal. She has an elementary school named after her in Sacramento, Irene B. West. Dad was crazy about education and he was a civilian in the Air Force. I always felt called to serve, to empower and ennoble as many people as I could, teaching, truth-telling, exposing lies, bearing witness, and being willing to live and die for something bigger than yourself. I had a passion and love of learning and wisdom that was inseparable from a love of music and the arts. I’ve never viewed them in any way as being separable. I’ve always loved to read, but I’ve also always loved to dance. [laughs]

QUESTLOVE: I remember your stories of using James Brown to study.

WEST: In my Hebrew class, exactly. I’d walk into that Hebrew class, man, I’d be so fortified with soul music—”Talkin’ Loud and Sayin’ Nothing,” “Super Bad Part 1 and 2,” and “It’s a New Day.” I just had it on a loop because I had been studying all night. I go in the Hebrew exam, man. A+. Damn, this brother fired up. I think part of it was that James Brown conveyed such a profound sense of self-confidence, self-respect, and a freedom to be himself. When I first heard “Cold Sweat” in 1967, I knew it was a fissure in time. I’d been listening to a whole lot of stuff. But “Cold Sweat” was a qualitative leap.

QUESTLOVE: And you recognized it instantly?

WEST: Right then. I was thinking, “We’re in a different world.” And musicians understood it, because they came running, man.

QUESTLOVE: That, to me, is one of the most beautiful things about music—to get that spiritual orgasm when you hear something that you know is going to change your world, or change the whole world.

WEST: It makes you feel brand new. It makes you feel like you’re part of a new era. It makes you feel as if there are new sources of power and new sources of dignity. I associated James Brown’s genius with a certain kind of dignity and a readiness to muster the courage to be himself.

QUESTLOVE: Have we lost that? And where was the sea change? I’ve been a DJ for 30 years. I would DJ in nightclubs with my dad, but now I DJ to conduct focus groups within myself. I purposefully conduct little experiments to see how the different demographics will respond. But my main, overall, broad assessment is that somewhere along the line—and I believe the year is ’91—black people lost their inner urge to express themselves. When you think of primitive movement and spiritual movement now, it’s white people you think about. Dave Chappelle makes fun of white people dancing, like at Grateful Dead concerts. But, seriously, the funkiest dancers, the most intense expression of body movement I see now is from white people when I put soul music on. Black people are now the wallflowers. Have we lost something?

WEST: Good God. That’s generational, though. Because my generation, you put on Lakeside, you put on Charles Wright & the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band, they’re going to move. Yeah, but that’s very sad, man. That’s very sad.

QUESTLOVE: How do you get that back? Does being downtrodden make us spiritual again?

WEST: I don’t think it’s just a matter of the material conditions; it’s a matter of the choices that we make. Our ancestors could have chosen forms of spiritual suicide and spiritual blackout, but they decided not to, even in the midst of slavery, even in the midst of Jim Crow. Great-great grandma could have chosen to commit suicide. But she said no, her kids said no. The love said no. “I choose to be on the love train, even under slave-like conditions.” That’s a choice we make. All we have had as a people, historically—amid the levels of hatred, the social death of slavery, the civic death of Jim Crow, the psychological death of hating one’s self, the spiritual death of giving up and selling out and caving in—all we have is a subversive memory, personal integrity, and courageous witness in the fight for justice. That’s all we’ve got. You do away with the memory, and people can’t hear the voice of a Glenn Jones or, my favorite, Gerald Levert. With no memory, you get very little artistic integrity, just a matter of stimulating people for the market, and then no creative witness.

QUESTLOVE: One of the biggest mistakes I made—I did an interview with [cultural critic] Touré that came out in 2003. And I kind of falsely assumed that America was going to come to its senses and we’d have a new president in 2004. I told Touré that we’re about to enter the war, but one thing I expect is that the music’s going to be great. Because, remember how during Vietnam …

WEST: We had some powerful music.

QUESTLOVE: I couldn’t have been more wrong. Literally everyone on my left-of-center side of the fence was rendered silent. We haven’t had a Lauryn Hill album in 12 years? No one’s really willing to take that risk. Remember, in 2003, Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks criticized Bush and the war, and they instantly went from [selling] 12 million units to … They broke up. A lot of artists saw that example, like, “Wait a minute, if three lily-white country singers lose their career for being political, they’re going to kill us.”

WEST: That’s real.

QUESTLOVE: I live in fear today, post-Ferguson. I live in fear of cops.

WEST: But we all live in fear. Courage is not the absence of fear. It is the working through and overcoming of fear. Brother Martin had fear. He just wouldn’t allow fear to determine his behavior. As human beings, everyone has stuff coming at them, and a certain kind of fear. But courage is being true to yourself, true to a sense of integrity. And that’s what is more and more difficult. But it does take place. Pearl Jam, Rage Against the Machine, brother Prince—to come back to our own iconic figure.

QUESTLOVE: How did you handle it, personally, when some of your then-colleagues at Harvard were like, “Whoa, you’re making rap records, now, sir?” Was it just dirt off your shoulder?

WEST: In every possible venue—from radio, with my radio show, to film, with the Matrix movies [West played Councillor West in the 2003 films The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions], with books, with essays, with television, and with the music—I’ve always viewed myself as a participant. So when brother Mike Dailey came up with the idea [for Sketches of My Culture], connected with my blood brother Cliff West, brother Derek [Allen], and myself, we got in the studio and said, “Hey, this is going to be a danceable education.” Nietzsche has a wonderful phrase in his first book, The Birth of Tragedy, where he calls for a “musical Socrates.” He says, “I want philosophy to take the form of a musical Socrates.” I said, “Wait a minute, black musicians have been doing that for a long time, so I’m just a small part of this great tradition. I’ve got the books out there; I’ve got the radio, TV. Let me move into music.” And it was just spoken word, because I wasn’t singing or nothing like that. I’ve always asked myself how I, as a writer, can be true to the voice of David Ruffin or Aretha Franklin. I never come close. Those voices have an integrity, honesty, decency, tenderness, roughness, insight, truth-telling, vulnerability. That’s my standard. I never reach it, but I’ll be damned if I’m not going to be on the road for it. Toni Morrison, Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, they’re real geniuses on the page, and their work aspires to the condition of music.

QUESTLOVE: We were in North Carolina and a friend of mine took me to a soul food spot. And southern cuisine is rather pricey now, caviar-level expensive, whereas the origins of southern soul food cooking was as scraps off the master’s table.

WEST: Leftovers. That’s right.

QUESTLOVE: I’m noticing that what used to tide us over, or keep us living, is no longer the standard of soul food. Michael Jackson’s musical director for the This Is It tour said that he would brag about how many ways he could remake grits for dinner.

WEST: Wow.

QUESTLOVE: In the inner city, take-out food is the new soul food. Chinese food now feeds the ‘hood. How is the cuisine that was formerly the lowest of the low—not fit enough for the big table—now the exalted, pricey standard? Are we losing our identity? What is our identity today when music is shared, worldwide, and food is unattainable?

WEST: We live in a predatory capitalist society in which everything is for sale. Everybody is for sale, so there is ubiquitous commodification—be it of music, food, people, or parking meters. Capitalism will devour anything for a profit. Now, there used to be a time in which there was a concern about quality, there was concern about the long term, so you had investment, but now it’s all short-term gain and commodification. That’s a fundamental shift, and part of the “financialization” of capitalism, in which banks have almost twice as much a percentage of profits that they did 30 years ago. There used to be corporations that produced products. Now there are just banks that produce deals, hedge-fund-driven banks and derivatives and those things. So what does that mean at the level of culture? It means identity is radically recast, more tied to markets, constituency, consumption patterns. And it’s all about the choice of the consumer. Now, on the one hand, it’s a positive thing, because you don’t want folks locked into eating grits all the time. It’s good to be cosmopolitan and get something from Ethiopia, something from Japan, something from Australia. The same is true with our music. We don’t want to fall into the trap of saying, “When you look at the present, you only see the worst. When you look at the past, you only see the best.” But the best is getting smaller. But this is true, not just in music, but in leadership, education—right across the board.

QUESTLOVE: What should we have learned from Ferguson?

WEST: We should learn that the vicious legacy of white supremacy is still operating. We learn that there are three dominant tendencies in a neoliberal society: financialized, privatized, militarized. And when it comes to black poor people, we get all three. Our public education is privatized, with big money at the top, so they don’t have resources for public education. The schools themselves get militarized, and the police are feeling more and more like an occupying army in the community. We are, as a people, among our poor especially, criminalized. They left Michael Brown’s body in the street for four and a half hours. The family can’t touch it, and then they take his body and throw it in the SUV. That’s a level of disrespect we don’t have a language for. You are responding to the militarizing attitude too many people had—not just police; white citizens have it toward black folk; many young black folk have it toward each other. We’ve privatized public life, public education, public transportation, public conversation-pushed to the side—it’s all privatized. For what? Big money. Where’s the big money go? Does it ever seep down to the poor? No. It goes up and hemorrhages at the top. One percent of the population owns 42 percent of the wealth; 22 percent of U.S. children live in poverty; almost 40 percent of children of color live in poverty. And the richest nation in the history of the world is a moral disgrace beyond description. The greed is running amok at the top. When you get all three of those together, you say, hmm, not just, “Here comes Ferguson,” but, “There’s going to be a whole lot more coming.”

QUESTLOVE: There are more Fergusons coming.

WEST: You ain’t lying, brother. We’re planning a massive civil disobedience in two weeks, in Ferguson. Right there, where the brother was shot. Massive. Try to fill the jails the way they did in Birmingham. And I’m going for one fundamental reason: to show the young brothers and sisters that we love them. To bear witness. Because too many of them feel unloved, unattended to, uncared for. Marvin Gaye raised the question, “Who really cares?” Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway raised the question, “Where is the love?” We may not be able to change the world, but we’ve got to be able to say, “We do love y’all.” And we are going to sacrifice. Not just with words, but with bodies. Young folk need to know that there are some old-school brothers and sisters that really, genuinely care. I am who I am because somebody loved me, somebody cared for me. I wouldn’t be able to utter a word if it wasn’t for their love and the care, and the least I can do is manifest that to the best of my ability, to the younger generation.

QUESTLOVE: Black prophetic fire.

WEST: That’s precisely what this book is about. Because when you really love folk, you hate the fact they’re being treated unjustly. And if you don’t do something, you’re going to cry out—that’s the kind of people we come from. At our best. Now, I’m not romanticizing black people, because we’ve got gangsters like everybody else. [laughs] But oh, Lord, we got some great ones.

QUESTLOVE: What three records can you not live —no box sets, no greatest hits, pure records?

WEST: Coltrane’s Love Supreme [1964], no doubt about it. Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On [1971] and Amazing Grace [1972], Aretha Franklin and James Cleveland and the Southern California Community Choir.

QUESTLOVE: Do you know about the accompanying film? Here’s what the world does not know: There is a documentary of her recording the album at the New Temple Missionary Baptist church in South Central L.A. directed by Sydney Pollack. The one problem is, she will not sign off on it. But it’s complete. They say it could change lives, because it’s a pure document of her in her gospel glory.

WEST: Wow. My God. The reason why I say that you’re a spiritual, artistic giant is because you allow the richest musical traditions to go through your heart, mind, soul, body, while retaining your own voice. And that is one of the highest levels of being alive, man. I talked to Sonny Rollins on Coltrane’s birthday last week. We went to [Coltrane’s] grave. And Sonny, he’s full of so much wisdom, and he’s from the same tradition. And the whole world knows we must learn how to live in the blues idiom. The blues is about compassion in the face of catastrophe. We black folk, we’ve been on intimate terms with catastrophe ever since we’ve been here. But you keep track of Howlin’ Wolf, you keep track of Bessie Smith, and you’re going to see some compassion, some creativity, in the face of catastrophe. And despair won’t have the last word.

QUESTLOVE: Three books I should not live without?

WEST: One is Anton Chekhov’s short stories. He is the closest thing to the blues in literature. Even deeper than the blues, because he doesn’t have any American taint of belief that tomorrow is going to be better. Toni Morrison’s Beloved, of course. That’s our great 20th-century American novel. The third text probably would be Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals. Just for intellectual integrity. Because he’s wrong. But he’s so profoundly wrong.

QUESTLOVE: [laughs] You’re recommending and challenging Nietzsche at the same time?

WEST: Oh, yes, because Nietzsche is so honest, and he’s got so much integrity. It’s just that his conclusions are unconvincing. So you go with the insight, you go with the effort. You go with the courage but you still disagree—I’ll put it this way: as a revolutionary Christian, that’s who I am, just like brother Martin, Nietzsche provides the most powerful and profound critique of Christianity in On the Genealogy of Morals. I have to wrestle with that critique all the time, every day. I acknowledge the profundity of the critique. But in the end, he’s still wrong.

QUESTLOVE: You’re still team Christian.

WEST: Exactly. The love supreme!

QUESTLOVE IS A MUSICIAN, AUTHOR, AND PRODUCER. HE IS BEST KNOWN AS THE DRUMMER FOR THE GRAMMY AWARD-WINNING BAND THE ROOTS. SPECIAL THANKS: UNION THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY.