ask a sane person

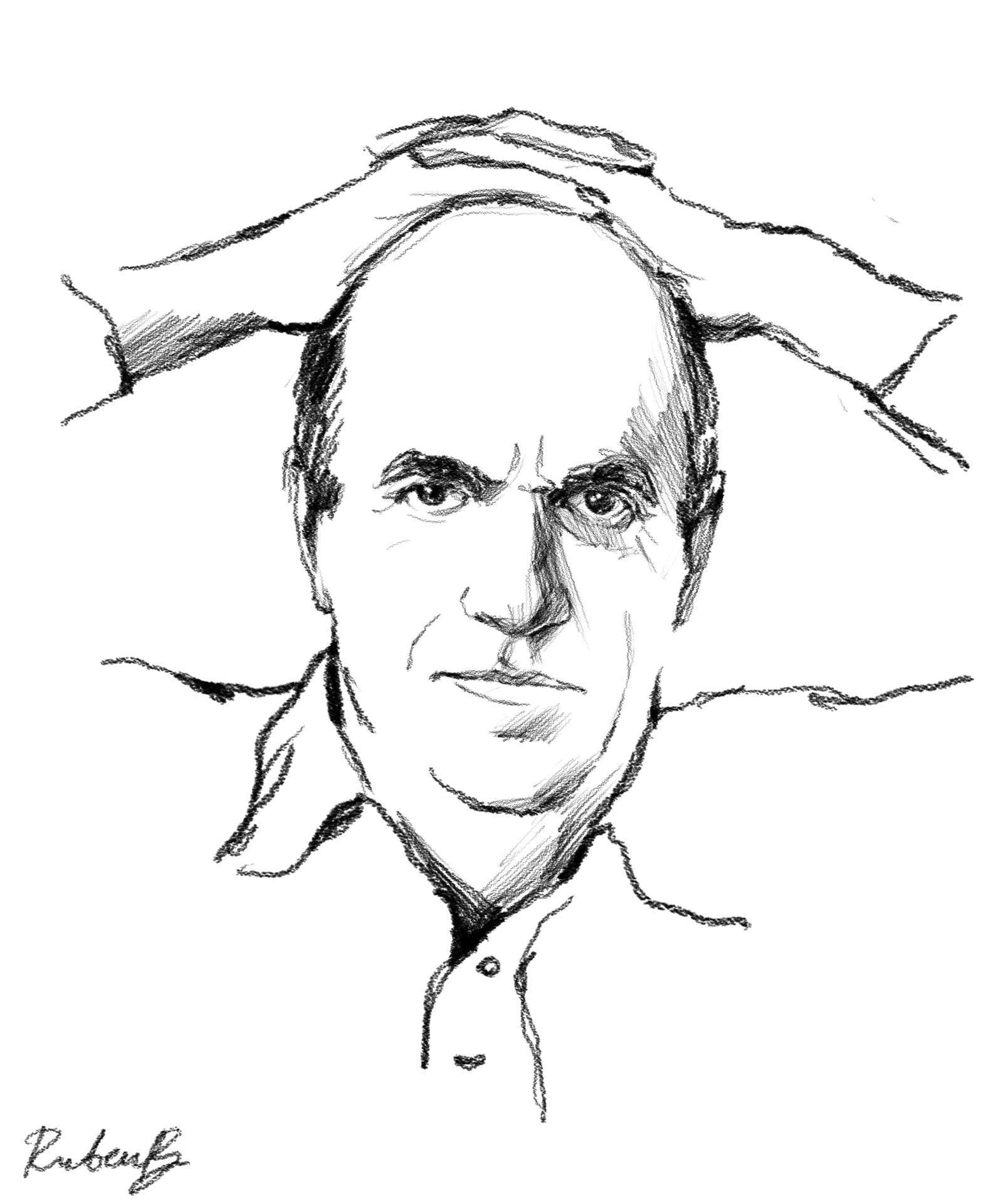

Colm Tóibín on the Inefficacy of Political Conversation

In the questions below, the Irish author and essayist Colm Tóibín gives a reason for his devotion to the United States: “The greatness of America has been the life of the mind and the life of the imagination.” The stirring, complex lives of both the mind and the imagination are precisely what Tóibín offers his readers time and again in his many novels, short stories, criticism, journalism, and poetry. No contemporary writer manages to capture the sweep of a period and yet fill it with such living, breathing, intensely mortal characters. Tóibín lives in New York, where he teaches at Columbia, but he has been spending the past months on the opposite coast, having just finished his next novel, The Magician, about the life of Thomas Mann. As Tóibín says, sometimes great art is the most we can hope for in this world.

———

INTERVIEW: Where are you and how long have you been isolating?

COLM TÓIBÍN: I am in Los Angeles in my boyfriend’s house. He is more or less the only person I have seen or spoken to face-to-face since March 10 when I came from New York.

INTERVIEW: What has this pandemic confirmed or reinforced about your view of society?

TÓIBÍN: It emphasizes the importance of politics and leadership. How come Austria, Germany, Cuba, Iceland, New Zealand, and the Scandinavian countries (except Sweden), among other states, handled the pandemic with exceptional care and other countries didn’t? Often, we like to think that politics is superseded by forces that are larger, more mysterious, and beyond our control. This pandemic lets us see that power can often be simpler and easier to name.

INTERVIEW: What has this pandemic altered about your view of society?

TÓIBÍN: I have learned that the inability of people like Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, and Boris Johnson to manage this pandemic comes from their politics. They themselves are filled with self-praise and grandiose talk. They cannot sit quietly and make a plan. Their politics involve contempt for those whose lives they have been charged to improve. They have made me long for modest politicians, ordinary ones.

INTERVIEW: What is the worst-case scenario for the future?

TÓIBÍN: I have been reading Don DeLillo’s novel The Silence, to be published in October. I think the next thing to worry about in America will be electricity. It will begin with outages here and there, and then we will grow used to them.

INTERVIEW: What good can come out of this lockdown? Are there any reasons to hope?

TÓIBÍN: No matter what good might come, it wouldn’t be worth all that misery and fear, pain and death.

INTERVIEW: What has been your daily routine during this time?

TÓIBÍN: Writers should keep quiet. I work every day, from about 11 a.m. onwards. I have done edits on a new novel, and written a novella and a story and a good few very long reviews and some new poems. Twice or three times a week, I play tennis (singles) with my boyfriend.

INTERVIEW: Describe the current state of your hair.

TÓIBÍN: I have problem hair to start with. I am bald, for one thing. Second, I had chemo two years ago and when my hair grew back, it was (and still is) like baby hair. And now, without a barber, it grows outwards and I look like a scarecrow. I don’t go out, but if I did, people would run when they saw me.

INTERVIEW: On a scale of 1 to 10, what is your level of panic about the current state of the world?

TÓIBÍN: I enjoy America and love hanging out with Americans. I think I liked America even before I came here. But things are bad in America and might not improve. How come Europe could build all these fast train lines and America can’t build one? Why are college fees so high? Why do the police swagger around the way they do? Why do Americans speak of the Founding Fathers so warmly when it is the very Constitution that is at the heart of the problem? It seems to me wrong that the president should have so much power.

INTERVIEW: Do you think there is hope for true racial equality in the United States? What is the first step in that goal?

TÓIBÍN: In 1964, James Baldwin wrote something which seems naïve now, perhaps the only truly naïve observation he ever made: “There is a limit to the number of people any government can put in prison, and a rigid limit indeed to the practicality of such a course.” This may be the only thing he got wrong. There seems to be no limit. Maybe the first step is to deal with the astonishingly high prison population in the United States and the astonishingly high number of African-Americans who are incarcerated. And the length of sentences imposed. And the general view that there is no justice available for many people.

INTERVIEW: How can America work to ensure more equality and justice on a day-to-day level?

TÓIBÍN: Education and health. Begin by giving everyone the same access to health and education. It is a long begin. But if it doesn’t begin, then there is no justice.

INTERVIEW: Do you think protests are effective tools for changing the system? How does it make a difference in the long term?

TÓIBÍN: Black Lives Matter is a most effective group. They operate with great intelligence and seriousness. The issues they raise are ones that should worry everyone. And, then, in a time of crisis, they offer a channel for anger and rage.

INTERVIEW: How do you personally channel your anger? Do you find anger to be a useful emotion?

TÓIBÍN: It is very hard not to be angry at the continued killing of African-Americans by the police. Also, when Trump announced early on in his presidency that foreigners from designated countries could not enter the United States. And recently I watched Immigration Nation on Netflix and I certainly felt anger at the tactics and policies of ICE and at some of the people employed by ICE and at the instructions they are now given.

INTERVIEW: Who are the young leaders of the moment that inspire you?

TÓIBÍN: There are some young novelists and essayists writing now who have subtle minds and original opinions and a good prose style plus a sense of commitment to telling difficult and complex truths. They include Jackie Wang, Brandon Taylor, Tommy Orange, and Esi Edugyan.

INTERVIEW: What’s the next step after protests in the streets? Where does the righteous rage go?

TÓIBÍN: It goes three ways—into electoral politics, into the writing of books and the making of films, and into forming community organizations.

INTERVIEW: Americans tend to find the topic of race uncomfortable. How do we start the conversation and address it directly?

TÓIBÍN: Everyone is really tired of what makes Americans uncomfortable. There is no need for a conversation. And there is no need for abstractions. Maybe start with voting rights. There’s a simple solution. Make voting mandatory, as they do in Australia, Belgium, Argentina, and other countries. If every single person in America voted or had the right to vote, it would be a different place. For an outsider, as I am, the idea of not encouraging every citizen to vote is very disturbing. No decent place can be built on voter suppression.

INTERVIEW: What thinker have you taken comfort in of late and why?

TÓIBÍN: Darryl Pinckney in The New York Review of Books: “If the U.S. is suffering, and the systemic racism of society is the underlying condition, then here is the cure: get rid of systemic racism.” I like the directness of that sentence.

INTERVIEW: Where did we go wrong? Like, what was the exact moment?

TÓIBÍN: An idea developed that a business or a company could have the same sort of rights as an individual has, and this has done real damage to America. And it seems to me that the president has too much power, and that the sort of power he has lends itself to grandiosity at best and sheer nastiness at worst. And I can’t see why we have both the Senate and the House of Representatives.

INTERVIEW: Which (admittedly totally unqualified) celebrity would you trust with the planet’s future?

TÓIBÍN: I don’t know enough about celebrities.

INTERVIEW: If you could stop time at one particular moment in your life, which moment would it be?

TÓIBÍN: Any summer in recent years.

INTERVIEW: What’s one skill we should all learn while in quarantine?

TÓIBÍN: How to stay in bed in the morning without feeling guilty. How to understand that, with a different president, this would all have been different.

INTERVIEW: What does our future as a nation look like?

TÓIBÍN: Not good. But the novelists and poets will still be working. We don’t know what books and films and works of art are going to be made, what music written, what songs sung. I grew up with feelings of awe about America not because of its politics or its inflated opinion of itself but because of Wallace Stevens, Emily Dickinson, Herman Melville, James Baldwin, and Elizabeth Bishop, and also Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, and also Ella Fitzgerald and Cole Porter. The greatness of America has been the life of the mind and the life of the imagination.

INTERVIEW: What prevents you from giving up hope in the human race?

TÓIBÍN: I have just read Marilynne Robinson’s new novel Jack, which is a prequel to Home, and it is immensely good. I have been listening to a lot of classical music in the lockdown—Brahms’s second string sextet, and Fauré songs sung by Frederica von Stade, and Bach Cantatas.

INTERVIEW: Who should be the next president of the United States?

TÓIBÍN: Joe Biden.