Catherine Lacey’s Novel Experiments

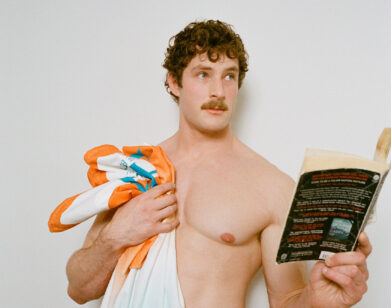

PHOTO COURTESY OF WILLY SOMMA.

“I’d run out of options. That’s how these things usually happen…” So begins Catherine Lacey’s genre-blending novel The Answers (out this week from Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Mary, a smart, young woman living in New York City, was content to exist within her own sphere until an extraordinarily painful and mysterious illness made this existence impossible. After years of specialists, resulting in looming piles of debt, a friend recommends an alternative form of healing—Pneuma Adaptive Kinesthesia (PAKing)—and it works. Looking for money to pay for the experimental treatment, Mary signs up for a job called “The Girlfriend Experiment” on Craigslist. She gets hired as the “Emotional Girlfriend” for an egotistical actor, Kurt Sky, who is trying to piece together the perfect relationship using different women to fill different roles.

Lacey’s winding prose unravels and gently probes Mary and the details of her relationships with tender care. The novel flirts with science fiction, playing around with psychological, chemical, and critical concepts of romance and “the self,” and raises questions about spirituality, self-health, and the true nature of love.

Lacey’s first novel, 2014’s Nobody is Ever Missing, won the 2016 Whiting Award, and last month, she was named Granta‘s Best Young American Novelists. Having already won several fellowships and other awards, Lacey is dedicated to keeping up with her writing and staying busy. She co-authored a nonfiction book called The Art of the Affair (Bloomsbury) that was released earlier this year, and her first short shorty collection, Certain American States (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), will be published sometime next year.

We recently spoke by phone.

SYDNEY RAPPIS: How would you describe this book to someone else?

CATHERINE LACEY: The immediate shorthand that I’ve been using lately is that it’s a book about people that want to answer questions that can’t be answered.

RAPPIS: So much happens in the book, but it never feels overwhelming. There seemed to be a balance between plot and meditation.

LACEY: I’m kind of a bad reader. When I’m reading, sometimes it takes me a long time to really get into the story. Also, I have a bad memory so sometimes it’s hard for me to keep track of really intricate plots—both as a reader and a writer. So I think the way I’ve dealt with it is that is I’ve gravitated towards simple first person books. And now as a writer, I tend to gravitate towards that as well. Even though there’s this third person chunk in the middle, in those individual chapters I’m just focusing on that one person—one perspective—at a time because it really helps me see straight. I want things to be both beautiful and readable. I’m not trying to alienate a reader, or make someone think they can’t read it because they like more commercial things. I hope that there’s room for any sort of mind to encounter the book.

RAPPIS: This plot talks a lot about women and their bodies and the self, so I was wondering if that came later or if it was always there?

LACEY: I think it’s just an inherent concern that I have. With Mary’s story in particular, it came out of an experience I had with Rolfing, which is a bodywork technique that sometimes people with scoliosis will get because it eases back pain. I have scoliosis, which is just a curvature of the spine you’re born with. The Rolfing is very specific, it’s like a painful massage on the connected tissue between the muscles and the bones, and it’s a pretty legit, not a “woo-hoo” kind of thing. But he was also doing energy work thing with it. It kind of opened me up to this question of, what if something is going wrong with your body. For women, this is often true because we are more hormonally complex, we have more complex bodies, so we have more things that go wrong with them. It is experiencing the mystery of the physical thing that you live in. I can read about all sorts of things that happen in the world, and I can find a wealth of information about things outside of me, but I can’t tell you right now if I have a tumor or not. It is possible that inside of me right now there is a cancer that I don’t know about, which is just so bizarre to me. You can know so many things about things that are far from you and things that happened way in the past, but you can’t know everything that is happening inside of you. I think in this book the female body is more foregrounded in the plot; it’s concerned with more than just the human body, but the female body and how it’s perceived and viewed and used in modern society.

RAPPIS: In so many different ways, too.

LACEY: Oh, yeah. And male bodies get used too. War is this phenomenal and grotesque use of the male body. I don’t think women are the only group of people suffering on this planet in this way, it’s just that the concern of this book is specific to the emotional labor that women do, the physical labor in relationships that they do, or historically have had to do.

RAPPIS: The experiment is played out as a business transaction, and is very scientific. But ultimately, it’s funded by this uber-famous celebrity, Kurt Sky, which complicates all of the motives. Was Kurt modeled after any particular movie stars? James Franco or Tom Cruise?

LACEY: No, I wasn’t thinking of anyone in particular. I think I was blending together every actor I’d ever seen, but also every man of a certain persuasion I know. You know, this kind of impenetrable, self-obsessed, big dreamer. Often something happened to them when they were young. We have this whole culture built around narcissistic men being rewarded for being narcissistic. This is bad, but now that I think about it, I was probably creating this mosaic of ideas and things I’d experienced. He’s obviously not a real person, but when I think about what I put into this mosaic, it has more to do with men I actually know than anybody that’s famous.

RAPPIS: Did you do any research for this book?

LACEY: I did acupuncture, which is actually pretty fucking helpful. I went to this great place in Brooklyn and it was like a community. It was just one big room, and you would go in and other people were there and this woman would come around and put needles in you and you‘d just mediate for an hour and she would take them out and you would leave and feel good. She kind of had a cult following. You loved her because she’s just delivering. It’s rare that there’s a person in your life that has that measurable and immediate an impact on you. You might have a boyfriend for a few months and you look back and you’re like, “I don’t know what I was getting from that relationship, I don’t know what he was getting from it, and it means nothing.” I think there are ways in which, no matter if you’re dating somebody or you’re married, you get some of your interpersonal needs met elsewhere. And they’re not necessarily all romantic—like a conversation with your coffee guy.

RAPPIS: There are many shades of relationships in the novel, and friendships are an important one, in this case a friend found later in life. Why did you make it a point to include this friendship?

LACEY: Growing up I was never the kid who had a best friend. I was never anyone’s first choice. But when I went to college I became really close with a few people and I’m still close with all of them, but I have this one guy who’s really my best friend. We’ve moved around, we’ve fought, I’ve hated him for a whole year, but he just understands me in a way that’s not familial and it’s not romantic. Sometimes you just find these people who are irrevocable from your life. I’m in a relationship that I’m totally happy in and just overjoyed. But friends, they fall under this broad category. These relationships are never celebrated in the way that they should be. In the beginning of writing this book, I was in a relationship and I didn’t want to fall into a routine of complacency. So I was thinking a lot about what I needed from that person, and what they needed from me, and in what ways we could change what we expected from each other. We were pretty adventurous about breaking down our relationship and trying to make it ideal. It didn’t work, but I learned so much from it so I don’t think it was a failure at all. I learned a tremendous amount about what my boundaries are and what my needs are. I think people don’t really challenge their preconceived ideas of what a relationship should be, and then because of that, people kind of fall into a routine and then they don’t question why relationships are put together the way that they are. Men are terrified of getting into a relationship, I think because they have this fear of the loss of self. You become somebody’s boyfriend, you aren’t your own person anymore. It’s a reasonable fear. Why would you want that? Nobody should. But I don’t think that women want that either.

RAPPIS: There certainly is an expectation that you need to find one person to be your romantic partner who is also your best friend, confidant, life coach, and cheerleader all wrapped up in one.

LACEY: Then, on the opposite end, people who are polyamorous lose a lot in that. You lose a lot of depth. A lot of people have a knee-jerk reaction to non-monogamy, but if you sit with it for longer and really look at it, compare it to the status quo relationship that’s always on a path—you date for this long and then you get married and after this long you have a kid—it’s like, why are we on this conveyer belt? At what point in that whole thing are you giving up what you believe in order to give people what they think they need? I think that’s worth examining and I don’t think we do that too much. It’s very tiring in a relationship to break it down to it’s component parts and think about what you mean to another person, and often if you do that, to really examine what’s really happening, I think that ends a lot of relationships because often people outgrow each other and they don’t even notice.

RAPPIS: It’s difficult to know how to grow in a relationship.

LACEY: A friend of mine’s parents have been together for a really long time and are really happy. I don’t know a lot of people who have parents like that. She asked them at one point how they were still together, and they said they were actually just lucky. They both have changed a lot, moved around and changed careers and raised kids and everything, but they were just really lucky. That’s the thing that’s amazing in a relationship, sometimes you see a relationship where one person’s career means everything and the whole relationship is built around supporting that career and then the other person takes care of the domestic. Balanced. I don’t know, maybe that’s not how it is. That’s all I can say from my relationship soapbox. I don’t know anything at all; especially if you spend years writing a book that’s exploring what you think are some statements about this topic. Ultimately I’m just questioning everything, every day. And my ideas tend to change too.

THE ANSWERS IS OUT NOW, FROM FSG.