Required Reading

Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham Talk to Janicza Bravo About Black Futures

Kimberly wears: Coat by Laquan Smith. Turtleneck by Telfar. Earrings by Brooklny Bleu. Jenna wears Turtleneck by Telfar. Jeans by Barragan. Glasses Jenna’s Own. Earrings (top to bottom) Bvlgari and Mateo Bracelets and Rings by Tiffany & Co.

In 1974, when Toni Morrison published The Black Book, a compendium of the Black American experience from 1619 to the mid-20th century, it filled such a gap in the library that an entire wing should have been built just to hold it. This December, the Brooklyn-based writers and curators Jenna Wortham and Kimberly Drew have coedited a book that will no doubt draw comparisons to Morrison’s seminal anthology. But in reality, Black Futures stakes out its own radical territory. Wortham and Drew have brought together a wealth of Black writers, thinkers, artists, chefs, activists, photographers, historians, musicians, filmmakers, poets, social-media stars—even a marine biologist—to give voice and breadth to the Black experience of today, as well as expanding those visions into the future, as a gift, as a reminder, and as a tool for the next generations. It’s a stunning, eclectic, and deeply inspiring album of creative offerings that promises discoveries and surprises and a refreshingly nonhierarchical approach to media. It’s also more community-minded than ego-advancing, which is so rare in the art world. In October, Drew and Wortham got on a Zoom call with their friend, the Zola filmmaker Janicza Bravo, to talk about cataloging the past, understanding the present, and choosing to believe in a future built on joy and jubilee.

———

JANICZA BRAVO: I’ve never released a book, but I’m curious if you two have a similar sensation as I do in film where every stage has some kind of lesson. In film, we have so many stages—preproduction, production, postproduction, and when the film comes out. Now that you are nearing the release of this book, having worked on it for so long, have you found any lessons in making it? Or how are you celebrating this win?

KIMBERLY DREW: I’ve been thinking so much about victory as an iterative process. For me, many of the victories of the book have already happened. So this is just another moment that I’m living through alongside Jenna, and it’s another incredible pivot in this journey together. But there was so much that went into making this, even just saying, “Okay, we can do this, we are worthy of this.” We’ve been living with this project for five years. But in a way, the life cycle of the book starts once it’s released into the world, and I think that’s what I’m not really prepared for. In “before times,” we would have had a big book party and enjoyed the celebration of it. But now, just talking to people who’ve seen it about their own choose-your-own-adventure path through the book is, to me, one of the best feelings—getting these really dialed-in responses to this thing we’ve been sitting on top of like a little egg in a nest for so long.

BRAVO: Ten minutes ago, I looked at my phone, and Donald, our president, is leaving Walter Reed hospital and is essentially telling everyone that, like, COVID is just not that big a deal. I got chills. Your book comes out in December and who knows where the world is going to be by then. So my next question is, how are you managing this moment when the global and political climate feel really close? They feel closer than I can recall them feeling in a really long time. How do you navigate that?

DREW: Our book was sold pre-Trump. We were putting together this project in the interest of recording this moment, responding to this moment, building generative energy around what we hope for our future generations. And then 45 became president. And very quickly there was this decision we had to make, whether it would be anti-Trump about Blackness. At the time we were both like, “No, this was always a project that was self-contained and not designed to be a criticism of all these other things.” I think it’s important to note that. But we had an interesting ongoing hurdle of figuring out when to begin and when to end. The question was, “How do you make something that is universal and represents an ongoing struggle?” Because in a Black cultural context, we see a lot of freedom and it’s bigger than these forces of evil that are playing out right now. And we can wrap our arms around each other and find these larger commonalities.

The model and activist Yves Mathieu, photographed backstage at the Pyer Moss Spring/Summer 2019 show. Pyer Moss Apparel LLC. Image courtesy the artist Amanda Williams.

JENNA WORTHAM: Kimberly and I just knew this book wasn’t about this administration. It just meant that it took longer to make because we really had to build in time for emotional and mental health and recovery. Because all of a sudden, very quickly, the landscape of the world we were living in just shifted dramatically and shit was going down. I think it added a different lens for us, but the mission itself was still the same. We’d been really inspired by the ways in which people were in dialogue on social media, and how conversations around what art is and what forms it takes and how it functions have changed or been leveled in really interesting ways. It became more about thinking of artists and writers and creators who were making work about the timelessness of essentially the Negro Problem in America. How are we going to talk about how we’ve all grappled with that? So this book will always feel like a blueprint, a map toward survival, a balm, a warm bath, a hug, a plate of food. It’ll just always be a dwelling or home. And I think, for me at least, when you ask how I’m coping with everything being more intense and closer than they were in recent memory, I’ve really been looking at how Black writers, artists, and thinkers were working in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. A lot of similar heaviness was happening around the same time, especially in dealing with globalism and grappling with the feeling of potential for change—as well as the sameness of this country. That’s really been illuminating for me, recognizing that we are still part of this continuum of struggle, which contains a lot of joy and excitement, but also grief. For me, it’s liberating to feel that connection backwards and forwards. We have been here, we are going to be here.

BRAVO: I’m thinking about one of the sections of your book that’s titled “Joy.” In this book, even when there is a lot of grief or pain or trauma, the ultimate takeaway I had from its totality is jubilee. And that word, “jubilee,” is from a piece written by Jasmine Johnson in the “Joy” chapter. What I particularly appreciated about the book was that you chose a lot of works by artists that might not be considered museum pieces. I’m in my late 30s and was very much raised to rely on the art critic. The critics decide what has value or what is worth discussing. And as I started to make work and realize that the critics really didn’t like me, I was like, “Oh, you can go fuck yourself. I’m still here!”

WORTHAM: We got to decide who was worth including in the book. Not The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times or The Washington Post. No, we decided, and what we chose came in a variety of media.

BRAVO: You’re both in Brooklyn, right?

DREW: Jenna’s on the Bed-Stuy side and I’m on the Bushwick side of Broadway. But I can walk to Jenna. I actually found my apartment because it was close to Jenna’s.

BRAVO: Really?

DREW: It takes, like, 20-ish minutes. Far enough that I won’t make her hate me, but not too far, in case of emergency. I can go and get Jenna’s packages when she’s away, which is how I like it. But I’ve been in Brooklyn for eight years.

WORTHAM: Ten years for me.

BRAVO: Jenna, you lived in San Francisco for a bit between Virginia and Brooklyn, didn’t you?

WORTHAM: Yeah, after college with some friends. I was waitressing full-time and then interning at a bunch of different places.

DREW: And then there was Oslo.

WORTHAM: I got a little tired of New York, and I went to live in Scandinavia for a while, and then I came back. But I’ve been here pretty nonstop. I did Virginia, then California, which was such a neurological reset for me, and then I came here.

BRAVO: California’s great, although it’s on fire. Do you ever have conversations about where you’re fleeing to when everything fails? Have you made your short list?

DREW: I don’t have flee energy. I’m very much a hunker down kind of bitch.

BRAVO: Maybe that’s because New York is not on fire. When I walked outside and there was ash on my car, I was thinking, “I maybe need to consider some other options.” Have you been in each other’s pod these past months?

WORTHAM: Being in a city as dense as New York, it gets a bit tricky, because we’re never really isolated. Especially now, even if things aren’t back to normal, people are going out. Going to the park a lot, having coffee dates outside, things like that. But in terms of the people I’m willing to do things with, that amount of trust, Kimberly is number one. It’s funny to watch it evolve. It’s funny to watch getting acclimated to saying things like, “What are your comfort levels? How social have you been?”

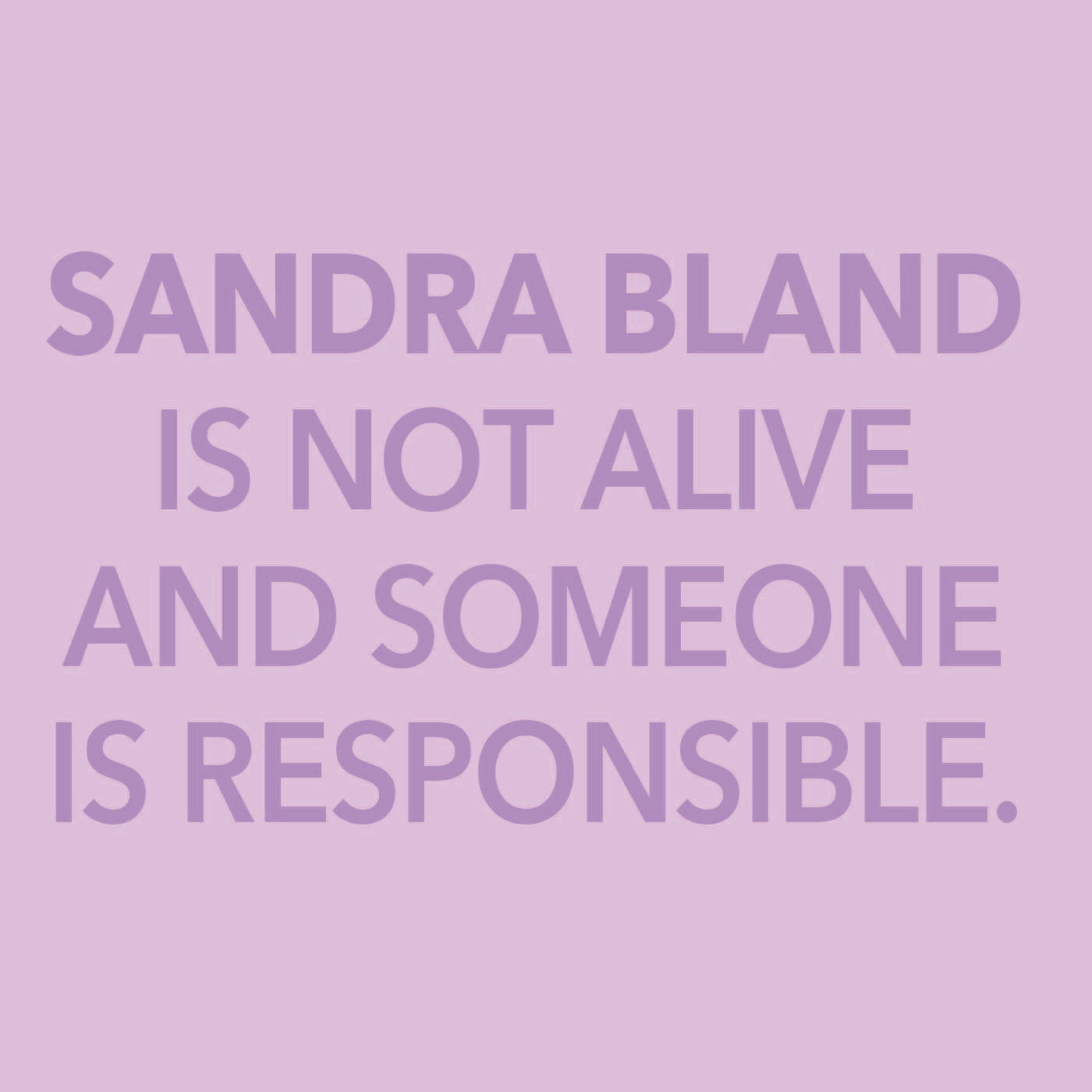

DREW: That feeling relates back to how we made this book. Choosing to believe, despite finding ourselves yet again at a moment of extreme despair, or yet again, in a moment of injustice. The uprisings; I was so fucked-up in June saying again in front of people, “Hands up, don’t shoot.” It sent chills down my spine. To still be saying those same things. There’s an essay in the book by Doreen St. Félix [“June Jordan’s Vision of a Black Future”] that’s about a futuristic architectural project by June Jordan, who is primarily known as a poet. It’s this Black quantum-time exploration that a lot of Black creatives are operating on, but it also deals in the ways we’re edited as we navigate this world.

BRAVO: I’m glad you mention that piece. I walked away from this book feeling so inspired. I’ve fantasized about making art, but I’ve always felt like I don’t know how, I don’t have access. I’ve created a list of reasons why I can’t. But so often while reading this book, I thought, “Oh, but I can.” Page after page, there is someone who looks like me. I think you’re speaking to many people, but I felt like you were talking to me directly. I felt like I had more potential than I even knew, if that makes sense. Oh, ladies, stop. Don’t make that face. [Laughs] Another essay I loved is Zadie Smith’s piece on Deana Lawson, when she talks about the subjects inside of her frame. She says they are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, and un-fallen. I know the feeling of shame around my roots, and Zadie so perfectly articulated what I love so much about Deana’s work. They are environments familiar to me, and they’re environments I’ve never seen held to a status before. Through and through, this baby you have made is pure celebration. Do you think this book is the first iteration of another book or chapter to come?

DREW: We’ve had many conversations about it being part of a larger project and what that looks like. I think the larger project of it is the way people feel inspired to develop their own version of Black Futures—specifically, to your note about critics and who decides what gets to be retained. One of the successes I hope this book achieves is that people understand the importance of their gestures. Understand that their contributions on Twitter or the care they take in themselves or their contributions in a recipe from the family book by putting their own twist on it—those things are worth retaining. Those things are worth celebrating. Worth being remarked upon.

BRAVO: That’s a big takeaway. There’s value in cataloguing. And I think you’re touching on the empowerment of the audience. Black Twitter has power, and that’s so radical. I can’t recall it existing prior to five, six years ago when I read the Zola story on Twitter [an epic 2015 account of sex work gone awry, written by a stripper named Aziah “Zola” Wells], which was the basis for my film. I don’t remember having something like that in my life before that moment, independent of my group of Black girlfriends. I never had a faceless Black audience that was able to elevate and pull things down at the same time. That’s never existed. At least not for me.

WORTHAM: It’s true. It’s really the Black internet. It’s Black Twitter, but then it’s also Black Instagram and Black TikTok. It’s Black Vine, it’s all of these platforms and spaces where we get to congregate and make things. One-up ourselves and each other, and have this response that felt so precious. I think one of the things that really galvanized Kimberly and me is how precious so much of the material in the book is, and how ephemeral it can feel.

BRAVO: You have an essay in the book by Rene Matić entitled “Black Pain is Not for Profit,” which touches on Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till’s dead body at the Whitney Biennial. I’ve answered this question a few different ways in my life, but I’m still curious who has the right to tell whose stories. For me, not even a decade ago, I just wanted my contemporaries to cast people who looked like me. I was tired of going to the movies and not seeing myself. And I had not asked this question before, I had not considered it, I had not thought about it. So my question is, do non-Black artists have the right to Black stories? Should men have the rights to women’s stories? What are your feelings on that?

WORTHAM: This question comes up all the time, and I feel like it would be an easier conversation to have if everybody had the same access, you know what I mean? I feel like the power dynamics and the hierarchies are such that often we don’t get to tell our own stories. We’re fighting so hard to get to tell them or build them or photograph them, or do whatever we want to do with them, that it’s egregious when someone else waltzes right in and has that right. And it gets praised, and that just becomes the narrative that becomes a default format for how things are done. That’s the part that drives me crazy. So, I don’t know. I think that’s where I’m landing, because sometimes it doesn’t bother me. Sometimes I think about Call Me By Your Name. That’s a movie that I really enjoy watching. I wish everybody in that movie were queer, but at the same time, I am totally happy with the outcome. I don’t feel an attachment to this argument around that story. But if your film, Zola, were being made by anybody else, I would be furious—this belongs to us. This was born of a particular niche and a platform that we created and devised. It’d be really hard to imagine a white person telling that story. At that point, it just becomes Spring Breakers and, sure, that’s fine. But I feel like there’d be some nuance missing.

BRAVO: Have you seen the Kathleen Collins film, Losing Ground [1982]. I showed it to my friend recently on DVD because it’s one of my favorite movies. He watched it and couldn’t understand why more people don’t know about it. He thought Noah Baumbach had basically made a career out of that kind of movie. And yet, when I watch Baumbach’s body of work, I think, well, it’s not to say that Losing Ground is not about Blackness, but you could pull out any of those characters and put them in his world. And for directors like him, my thinking is, “Can’t you just write and cast a fucking person that looks different?”

DREW: In general, I’m always frustrated in these conversations around representation, because there will never be enough. There will never be a quota that is met. We have to have a larger conversation about what it means to have the rights to something. Is there consent and how are these things used and what are the historical implications? We need to have slower conversations about how these things are sprinkled about the world. I think about The Incredible Jessica James [2017] and, first of all, I love that actress [Jessica Williams], but the film was difficult for me because it felt like they just took a brown crayon over a character that Lena Dunham had written. Her entire universe was not in any way reflective of anything specific. I believe so much in cultural specificity. And that doesn’t mean that every Black person is the same, by any means, but just that nobody else in her universe was also Black, which is absurd. I don’t think there’s a race of people that exists completely sovereign from their folks. But the larger moral question of that is a really profound one. It’s different when I see a creative who’s willing to do the work of asking questions and making sure that all the sources are cited, and who understands that there is violence in telling someone else’s story, although I’m sure there are ten examples where that doesn’t make sense.

BRAVO: That’s the part I get muddy on. I want there to be more integration in front of the camera, but I want it to be considered, right? There are moments when I have seen nonwhite characters and they seem to have no dimension. Or there’s this trend that happens in TV comedies where all the nonwhite characters are inherently good. There’s nothing wrong with them. They’re surrounded by complicated, difficult white people, and they’re just good.

WORTHAM: I guess it goes back to our respect for these digital platforms. We don’t necessarily have the faces that we want on screen or in books, but we have them on all these platforms. The flip side of that is that it’s very easy to appropriate and steal and repurpose. I thought what was incredible about the Dana Schutz piece was that Parker Bright stood in front of it. If she had the right to make that, then someone had the right to protest it, and I think all of it is good. We want to remember and remind people that all of these things can exist. It’s important to have nuanced conversations about it without one right or wrong outcome.

BRAVO: Without picking your favorites, can you spotlight a few pieces from the book that you feel exemplify the book’s thesis?

WORTHAM: It’s challenging because there are so many things in the book that we both love. There are also so many things in the book that didn’t get realized. In the beginning of the process, we had this dream of including some pieces in Braille. We wanted more pieces in Spanish and French and Zulu.

DREW: I don’t think that there’s any piece that can be extracted without establishing some weird hierarchy. But one of the pieces that I think of a lot in relationship to the book is Pierre Serrao’s coconut-bread recipe, because it’s a family recipe that Pierre as a chef has recreated, and then I realized that his cousin is an artist, and so his cousin illustrated him for the book. For me, it’s just this multigenerational, Black familial remix and innovation and testimony. And I think recipes are one of the few ways that many Black families are able to pass tradition along. And I hope people will understand that, especially for us as talented, amazing Black creatives who are reaching beyond our ancestors’ wildest dreams, we need to acknowledge our ancestors, their dynamism, and appreciate the gifts that they’ve left for us.

WORTHAM: The food recipes really blew our minds in terms of the potential for the book. We can talk about Black creativity and Black legacy and Black history and Black excellence. But food is something that’s just so deeply resonant and important.

BRAVO: A year or two ago, I’d written something for a magazine that was supposed to be about immigrants who are first-generation. I’m first-generation. And I just ended up writing a recipe and turned it in. They were like, “Oh, do you want to add anything?” And I was like, “Nope, this what I have to say about it. This is what the amalgamation of feeling like I have no country is for me.” That’s when I feel my most pointed, when I think about the things my mother or my grandmother or my aunts have cooked. They seem to be spaces devoid of pain and trauma when we were talking around food.

WORTHAM: Food can be a stand-in for so many other expressions of love that might be harder to name. I think about my family and how it was hard to get certain stories out. People don’t want to relive grief. They don’t want to relive pain and trauma. This is another way of answering what it was like growing up.

BRAVO: There’s so much in this book. How did you edit it?

WORTHAM: We stopped putting things in the book because we had to get it published. The publishers were, at some point, like, “You need to stop adding things in the book so we can go to press.”

DREW: Jenna and I are both writers and cultural practitioners, and when we’re not doing that, we’re publishing online. There’s this way that everything we do always feels like a to-be-continued ellipsis. But this was different. Pens down, step away from your creation.

BRAVO: I loved Alisha Wormsley’s inclusion in the book, “There Are Black People in the Future.” That sentence! It reminded me of this Richard Pryor album Bicentennial N****r [1976]. There’s a part that goes something like, “They had a movie of a future called Logan’s Run, and there ain’t no n****s in it. I say, well, white folks ain’t planning for us to be here. That’s why we gotta make movies. Then we’ll be in the future. But we’ve got to make some really hip movies. We made enough movies about pimps. White folks already know about pimping, because we’re the biggest hoes they got.” I quoted that because the book is called Black Futures and I wanted to end with that morsel of Richard Pryor in our current dystopian moment.