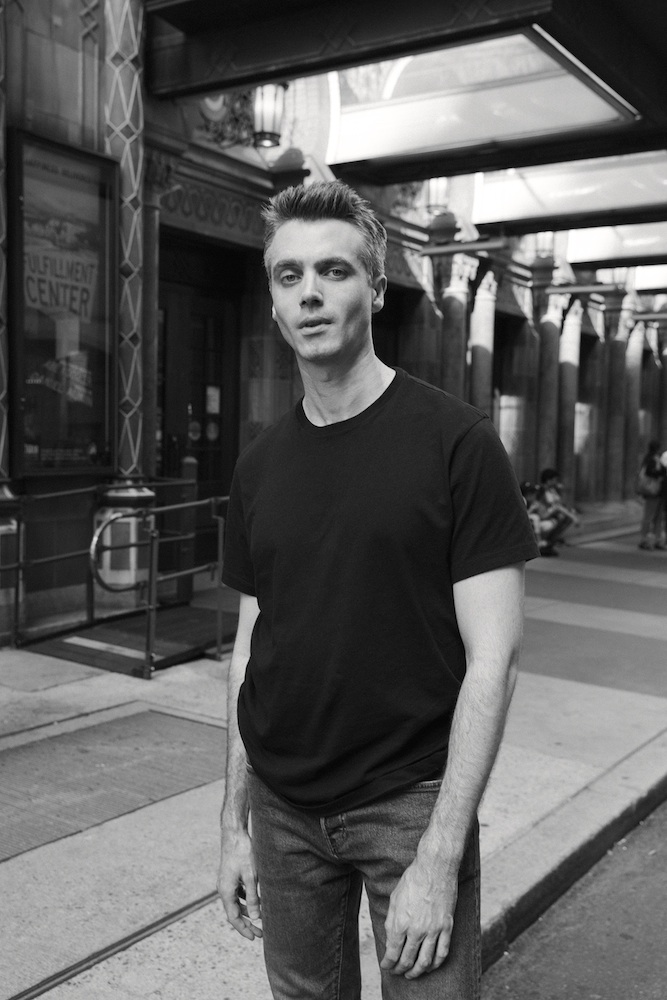

Abe Koogler

ABE KOOGLER OUTSIDE THE MANHATTAN THEATRE CLUB IN NEW YORK CITY, JUNE 2017. PHOTO: ERIC AKASHI. GROOMING: TAKASHI ASHIZAWA USING M.A.C. COSMETICS.

Despite its title and setting, Fulfillment Center, Abe Koogler’s new play, which opened yesterday at Manhattan Theatre Club, is not about a shipping warehouse. If you are interested in the inner-workings of e-commerce, look elsewhere. Instead the uncanny, existential promise of a fulfillment center—”Happiness. Delivered,” as the play’s tagline reads—serves as a launching pad for Koogler, and animates the play’s four characters, who are all looking for happiness in their own, mostly misguided ways.

The story centers on Alex (played by Bobby Moreno), a 30-something from New York who moves to New Mexico to run a fulfillment center for the holiday season. His girlfriend, Madeline (Eboni Booth), simmers with resentment over being displaced to the desert, where, in part because of her race (she is black), she feels unwelcome. Alex meets Suzan (Deirdre O’Connell), a washed up folk singer on the run who takes a job at the center. And Suzan meets John (Frederick Weller), a mysterious and rough-hewn local. Soon all of them are brought together and splintered apart.

This is Koogler’s second New York production. His first, Kill Floor, which premiered in 2015 at Lincoln Center, centered around a slaughterhouse, another setting both unremarkable yet deeply removed from our everyday experience. It earned the now 32-year-old playwright a Kennedy Center Paula Vogel Award and a Williamstown Theatre Festival Weissberger Award. In Fulfillment Center, Koogler has refined his tender, true-to-life style, with dialogue that is sometimes wobbly, sometimes brilliant, and a near-empty stage that evokes the melancholy solitude of New Mexico and its inhabitants.

In the off-hours quiet of Manhattan Theatre Club’s space on 55th Street, we spoke with Koogler about the play, irrational characters, and making the transition from actor to playwright.

MATT MULLEN: I was very excited about this play because besides being a fan of your work, I went through a phase where I was really interested in fulfillment centers. It started after I read that piece in The New York Times about Amazon’s insane corporate culture. Not that your play is about fulfillment centers, per say, but I feel like they serve as an important metaphor. So lets start there: why fulfillment centers?

ABE KOOGLER: I tend to get interested in processes and systems, specifically the backend of processes that we only see the front end of. My first play in New York, Kill Floor, was about a slaughterhouse. With that, I started thinking not only about what it takes to get a hamburger to our plates, but also about the physical landscape of a slaughterhouse. I consider that part of my mission as a playwright—not to expose anything, or make a really obvious political point, but just to follow my own interests and figure out, say, what it takes to order an air conditioner and get it sent to our door two days later. So I, too, became obsessed with fulfillment centers. I had a friend who was running one, like the character in the play, so I talked to him about what it was like. Of course in a broader sense I was thinking about the idea of fulfillment. We live in a time where, with a certain amount of privilege, every one of our physical and material desires can be satisfied fairly easily and quickly and painlessly.

MULLEN: Or can they?

KOOGLER: Or can they! I think in terms of material desires—yes, if you have the money. But spiritual fulfillment and happiness is an entirely different thing. So the play is about four characters who are looking for “fulfillment”—not to put too fine a point on it. I started the play as I was turning 30. And there was so much I was still looking for and didn’t understand; I felt like I was coming up against these big questions in a way I hadn’t been since I was 21.

MULLEN: You’re saying the fulfillment center was an entry point to explore these questions?

KOOGLER: I just think all the characters in the play are lost and adrift in some way. You have these two characters in their 30s, they know they’re supposed to get married and settle down into jobs—they’re like me and a lot of the people I went to school with. Yet both of them feel like something is off in their lives, that there’s some part of them that they have not yet confronted or dealt with. In this 88-minute play, we see them confront those things.

MULLEN: There is a lot of anger in these characters. It’s most latent in Alex and Madeline, because on the surface they’re high-achieving and put together individuals. But there’s darkness within them, and we see it erupt. What was your thinking with that anger? Was it something you were interested in, or did it just come along with the characters that you were trying to build?

KOOGLER: I’m interested in characters that feel at odds with the world in some way, who feel like they don’t quite fit into the box that has been created for them. With that feeling of estrangement can come feelings of great anger that to these characters feels sort of inexplicable. I’m also interested in characters who don’t understand what is going on inside of them—who have moments where an emotion emerges or an idea emerges that they’re not fully in control of and can’t explain rationally. I try as a writer not to rationally explain everything characters do. Because I don’t think they understand it, and I don’t think we should try and understand it or rationalize it.

MULLEN: I have to say I was really surprised when Madeline goes on the date with John.

KOOGLER: Yes. My sense is that she’s been acting up for a while. She’s been drinking, she says something to Alex to the effect of “I’m done with that, I told you that,” and I think she’s either talking about drinking or she’s talking about risky sexual behavior. There’s a darkness in her, again, that is something she doesn’t have words for and can’t quite figure out how to enact in her real life. And when she actually comes face-to-face with it in the form of John, it’s too much for her. She finds it scary. But she needs to come up against that darkness in some way. So that’s why she engages in this risky behavior.

MULLEN: Where did these characters come from? Were they inspired by anyone in your real life?

KOOGLER: This is the less rational part of the process. If I sit in front of my computer for long enough, they will emerge. In the case of Suzan, I’d been listening to a lot of Joni Mitchell. Especially this song “Woodstock.” I was listening to a version of the song that she played in a live concert that was recorded called Painting with Words and Music in the early ’90s. And I was toggling between that recording and the original recording, and her voice has changed so much, the style of the song is much more elongated and spare in the later version. Thinking about the impact of time on that song, on Joni Mitchell, and on everything that Joni Mitchell represented, gave birth to this Suzan character, who idolizes Joni Mitchell and is, in some ways, a distant, less successful echo of her.

MULLEN: Speaking more generally, where do your plays come from? An idea? A setting, a stage picture?

KOOGLER: Usually it’s a location that’s interesting to me. In this case I was thinking a lot about New Mexico, because my parents had moved to New Mexico a few years prior. I had these experiences of getting off the plane in New Mexico after being in New York and… well, in New York everything is very present tense, there’s very little time to think. So to get off the plane in a place like Albuquerque, I mean, the airport is silent. So it’s very existential and you become aware of geological time—a whole different time scale than what we’re aware of in New York.

MULLEN: What do you mean by geological time?

KOOGLER: I mean the fact that underneath us is a planet and a solar system that is operating on a whole different time scale. Maybe a less vague way to say this is that you can come up against stark existential questions in the desert landscape. You step outside at night and you hear coyotes in the distance and you’re just surrounded by total darkness. It inspires a different set of thoughts.

MULLEN: What was your childhood like? What did your parents do?

KOOGLER: I grew up on an island near Seattle. My dad is a carpenter so he worked for himself. He would drive off every morning to build a deck or a house or whatever it was that he was working on. And my mother was a therapist. She taught parenting classes too, so we were heavily… nurtured children. [laughs] From a very early age I started acting, and that was a great community. Being on stage was the one place where you get attention and got to shine, in a certain way.

After college, I moved to New York to be an actor. I spent about a year trying to do that, and was spectacularly unsuccessful. I remember I got cast in this short film where I had to play a coke addict. And I dealt with my anxiety about it by not doing any preparation whatsoever, including thinking about how I was going to portray a coke addict. So I remember the day we had to shoot me having a coke episode—I don’t even know what you call it—I was on screen and there were 20 people watching me, and I was just trying to make this shit up as I was doing it. And I felt so much shame, and that day was the last day of filming and I left and I was like, “I don’t have to do this anymore.” So I shaved my head, and I felt a profound sense of relief. I never acted again.

MULLEN: And when did playwriting begin?

KOOGLER: Then I took a playwriting workshop in the city and it was almost a physical sensation. I felt all these things unlock in my mind and this whole new set of possibilities open up. I also felt like what I found challenging about being an actor is that you’re at the mercy of other people’s material. So I was spending more time being critical of what I was doing than actually doing it. So for better or for worse, to have control over what I’m putting out in the world is more satisfying. And being a playwright is just an excuse to read and think about whatever I’m interested in.

MULLEN: When has a playwright “made it”?

KOOGLER: I don’t know. I feel like I’m at the very beginning of what will hopefully be a career. I think getting a first production in New York City involves so much luck and good fortune. And so many brilliant playwrights don’t have that happen for them even at an Off-Broadway level. So to pass that first hurdle for me, it felt like a milestone. But I think every playwright probably feels—like any artist—they’re only as good as their last play. So catastrophe always looms. You just have to be thankful for all the things that are emerging and accept all the good things that are happening. If someone doesn’t like it, or if I see an audience member have a certain reaction to the show, I don’t take it personally the way I used to. It’s weird to have so much real time feedback to something you’ve made. And it’s weird getting used to sitting in your own embarrassment. It’s part of the job I think.

FULFILLMENT CENTER RUNS UNTIL JULY 9 AT MANHATTAN THEATRE CLUB / NEW YORK CITY CENTER STAGE II.