PARADIS ICONS

A Taste of Paradis: Joan Didion, in Conversation with Mark Marvel

Over its 258-year history, Hennessy has pioneered and elevated the art of cognac, a spirit fit for kings and queens. Interview hasn’t been around quite as long – just 54 years – but we like to think we, too, have curated conversations and photography that aspire to a similar level of elegance and sophistication. In honor of Hennessy’s storied Paradis marque, we poured through the Interview archives to recirculate conversations with personalities, entertainers, and icons who personify the brand’s spirit of refinement, grandeur, and artistry. Today, we revisit the September 1996 issue, where the comic book icon Mark Grunewald (a.k.a. Mark Marvel) dropped by the late, great Joan Didion‘s pristine, oft-photographed Upper East Side apartment for a conversation on conflict reporting, slow writing, and the advantages of being a “nag.”

———

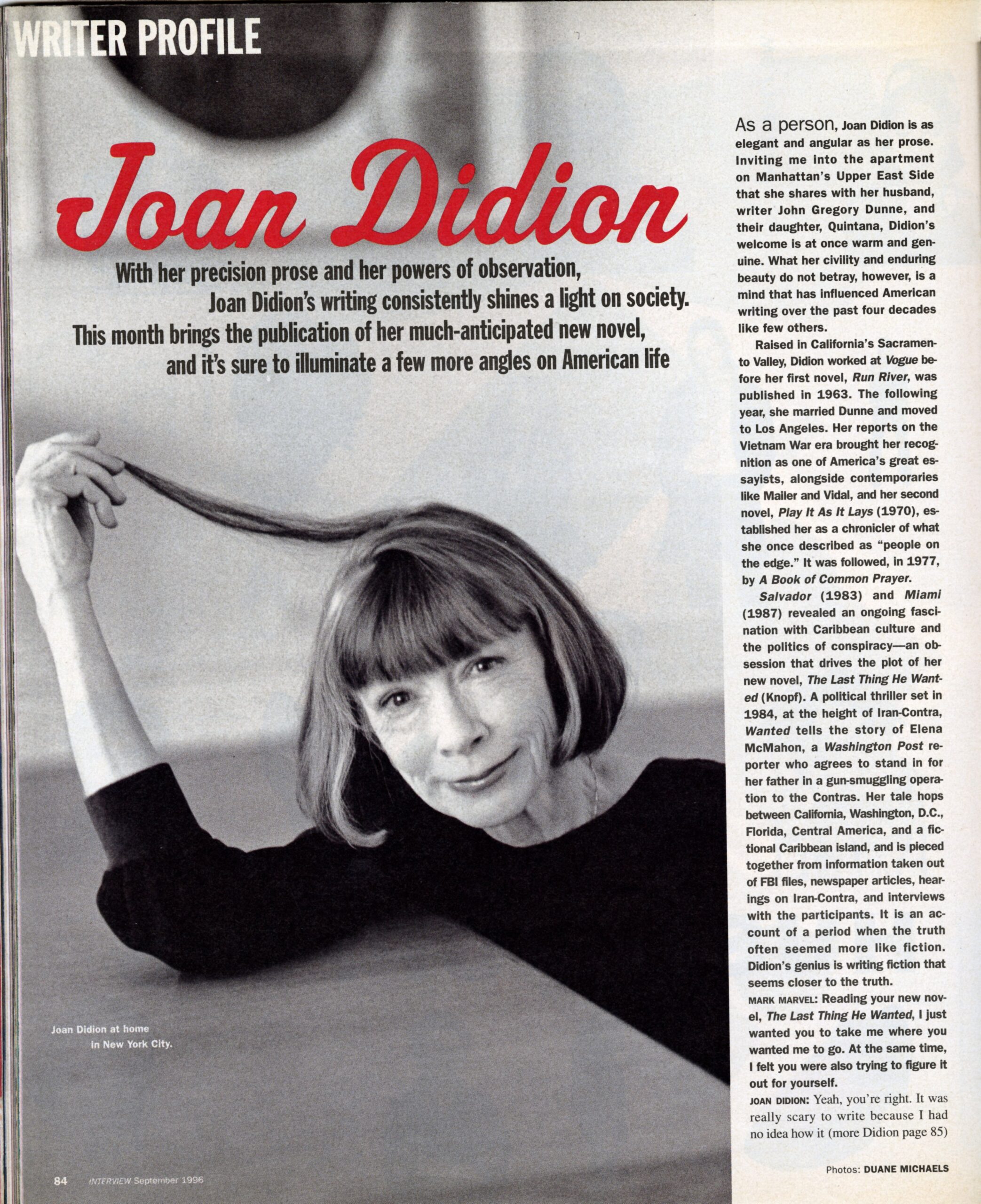

As a person, Joan Didion is as elegant and angular as her prose. Inviting me into the apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side that she shares with her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne, and their daughter, Quintana, Didion’s welcome is at once warm and genuine. What her civility and enduring beauty do not betray, however, is a mind that has influenced American writing over the past four decades like few others. Raised in California’s Sacramento Valley, Didion worked at Vogue before her first novel, Run River, was published in 1963. The following year, she married Dunne and moved to Los Angeles. Her reports on the Vietnam War era brought her recognition as one of America’s great essayists, alongside contemporaries like Mailer and Vidal, and her second novel, Play It As It Lays (1970), established her as a chronicler of what she once described as “people on the edge.” It was followed, in 1977, by A Book of Common Prayer. Salvador (1983) and Miami (1987) revealed an ongoing fascination with Caribbean culture and the politics of conspiracy, an obsession that drives the plot of her new novel, The Last Thing He Wanted (Knopf). A political thriller set in 1984, at the height of Iran-Contra, Wanted tells the story of Elena McMahon, a Washington Post reporter who agrees to stand in for her father in a gun-smuggling operation to the Contras. Her tale hops between California, Washington, D.C., Florida, Central America, and a fictional Caribbean island, and is pieced together from information taken out of FBI files, newspaper articles, hearings on Iran-Contra, and interviews with the participants. It is an account of a period when the truth often seemed more like fiction. Didion’s genius is writing fiction that seems closer to the truth.

———

MARK MARVEL: Reading your new novel, The Last Thing He Wanted, I just wanted you to take me where you wanted me to go. At the same time, I felt you were also trying to figure it out for yourself.

JOAN DIDION: Yeah, you’re right. It was really scary to write because I had no idea how it was going to work out. I didn’t know until I finished the story.

MM: There’s also an element to the book that feels very researched.

JD: It wasn’t so much research on my part. I was just reading an awful lot of really strange, wonderful material as the Iran-Contra story unfolded. I also read a lot from the hearings on the Kennedy assassination and government documents that came out about the war in Vietnam. The Government Printing Office was my godsend there. They put out this fantastic series called Vietnam Studies. The book I liked best was called Base Development in South Vietnam. It told you how to lay down the matting to build your own airstrip. [both laugh] I like stuff like that. And when you’re writing a novel about Iran-Contra, knowing things like how to build your own airstrip—well, things start falling together in a useful way.

MM: Are you a crisis junkie? Does it give you an adrenaline rush to imagine these crisis situations your characters are part of?

JD: Yes, yes, yes. I’m not very interested in the day-to-day. You know, those novels where people cross the street talking to each other. They’re sometimes very restful to read, but I don’t know how anybody writes them.

MM: I don’t think any of your characters would read them either.

JD: No, probably not. [laughs] I expect something to happen when they’re crossing the street. To me it’s hard to imagine that they don’t get run over.

MM: By an unmarked car. [both laugh]. You’ve written extensively about Cuba and El Salvador. What’s your interest in that part of the world?

JD: I have been attracted to certain places where conspiracy is a constant, where it’s the way people operate. In Caribbean politics, for example. And by Caribbean I mean all the countries that border on the Caribbean. I’ve never written about Cuba per se, just about the Cuban community in Miami. I got interested in Miami in the ’60s, after the Kennedy assassination. My husband and I were just about to get married and move to California. Everybody was saying that California would be the wave of the American future, that everything that happened in California would radiate throughout the rest of the country. I did not think this was true. It seemed to me that the country was more likely to be [influenced by] the strip from Miami to the Gulf. For this book, my interest in El Salvador came from the fact that the United States was down there playing some kind of role nobody seemed to understand. I remember reading the paper one morning, and this staggering stuff was coming out of El Salvador. My husband and I had no idea what the United States was doing there. He and I just decided to go down, and it was much more interesting than I had imagined from reading the Los Angeles Times.

MM: In The Last Thing He Wanted, there’s a feeling that the truth doesn’t really exist. All of the information, all the facts, are off the record, so that the truth is never acknowledged.

JD: Have you ever been in the White House Press Briefing Room?

MM: No.

JD: Well, every afternoon there’s a briefing. This deep voice comes over the loudspeaker and says, “There will be a briefing on such and such and the briefer will be so-and-so from the State Department. But this may only be attributed to a high-placed administration official.” [laughs] Then you see it in the paper the next day: “According to a high-placed administration official.” [both laugh] It’s totally fantastic.

MM: One of the most notable aspects of your novel is its terseness.

ID: You know, I stopped doing description a long time ago. If I start describing something, I put myself to sleep at the type-writer. In this book, even the characters are very sketchy, which is kind of a risk. But to move the story fast enough to keep you right there with it the whole time, the characters have to be kept at a remove. And I wanted to do something that moved very fast, faster than I’d done before.

MM: Let’s talk about something that’s happened a little slower. This is your first novel in twelve years. What took you so long? [both laugh]

JD: I did not have a good time writing Democracy [her last novel, published in 1984], so I wasn’t eager to get started again. And when I did finally start this one, it was very easy to set it aside and do other things, like go report on something more current or work on a movie. Plus, I’ve never written novels very fast. So I just let time go by and then a couple of years ago I started feeling the impulse again pretty strongly.

MM: What is “the impulse”?

JD: To make something new. And for a while you don’t have any conviction that you can. I don’t mean new in the world. I mean new for you. People who make pots must feel the same way. You don’t want to make the same pot all the time. I was very afraid of making the same thing.

MM: Didn’t you also feel a certain compunction to tell this story because it was becoming buried?

JD: Yes. It was a period that I didn’t want to drop into nowhere. Because I’m a nag, you know. I always think that I’m going to tell people exactly what’s going on and they’re going to listen. That if you can convey a situation exactly as it is—if you can give someone the weather, make them feel it—then they will see it the way you do. I always thought that was the writer’s function—to make people see. Then I realized that no matter how much I tried to write exactly what I saw, the reader was seeing it at a remove. There was a screen [created by] what the reader already believed—a screen of, “That’s not what the paper says, that’s not what I saw on—”

MM: CNN.

JD: Yes. So that’s when I started thinking of myself as a nag.

MM: What do you think it means to be a nag at this particular moment?

JD: I don’t know, because I just keep on doing it without any sense that it makes any difference to people. Still, it is simply my little duty to keep on doing it. [laughs] We all have our little tasks, our little rows to hoe, and that seems to be mine. I’ll just keep doing it, I guess.