Yoko Ono

John Lennon dubbed her the world’s “most famous unknown artist.” But for 40 years Yoko Ono has been expressing herself in a variety of mediums. Last year, the first American retrospective of her work, Yes Yoko Ono, opened at New York’s Japan Society Gallery. The exhibition will travel across North America and Asia for the next two years and features around 130 works from the 1960s to today-conceptual paintings, installations (including a telephone that Ono randomly places calls to), video displays and her peace collaborations with John Lennon, as well as more recent work.

The artist’s versatile audacity and dogged persistence have already inspired a fresh generation of musicians and artists; Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon happily agreed when Interview suggested arranging a conversation on art and life with Ono. Gordon herself has had a busy, creative year: Sonic released a new album, NYC Ghosts and Flowers (Uni/Geffen); and “Kim’s Bedroom,” Gordon’s multimedia art installation, which included contributions by other creative friends, including director Spike Jonze, was exhibited at galleries in the Netherlands and Japan.

KIM GORDON: Hello, Yoko. How have you been?

Yoko Ono: Well, it was a very busy year for me because it was John’s 20th anniversary [of his death] and his 60th birthday year and on top of it we had that parole board thing. [Lennon’s killer, Mark David Chapman, was denied parole at a hearing in October 2000.]

KG: Your show [Yes Yoko Ono] is incredible.

YO: I’m glad that you liked it.

KG: It was amazing. It just brought back so many memories of work of yours that I’d forgotten about, and there were lots of things I’ve never seen. Most people I’ve spoken to about the show talk about that telephone piece and . . .

YO: Oh, I was just going to ask you, was the telephone ringing at the time you were there?

KG: No, it wasn’t! And everyone’s like, “Does she call?” I was talking to somebody last night and she said that when she was there you did call that day and the guard told her you call about three times a week. I’m curious, do you call at regular intervals?

YO: Well, I have the phone numbers on the wall and whenever I notice it I think, “Oh, I wonder if it’s a good time to call?” It’s not regulated at all.

KG: What do you say when you call?

YO: I play it by ear. They start saying something about their experience and we talk. Some of them think it’s a computer. Once they know that it’s me, they get very shy and want to pass the phone to somebody right away.

KG: That intimacy in public-I guess they don’t actually expect it.

YO: Exactly. The phone shouldn’t be threatening. You can’t see the person, it’s just a voice. But for some people it’s really nerve-wracking.

KG: My favorite piece is the cutting film.

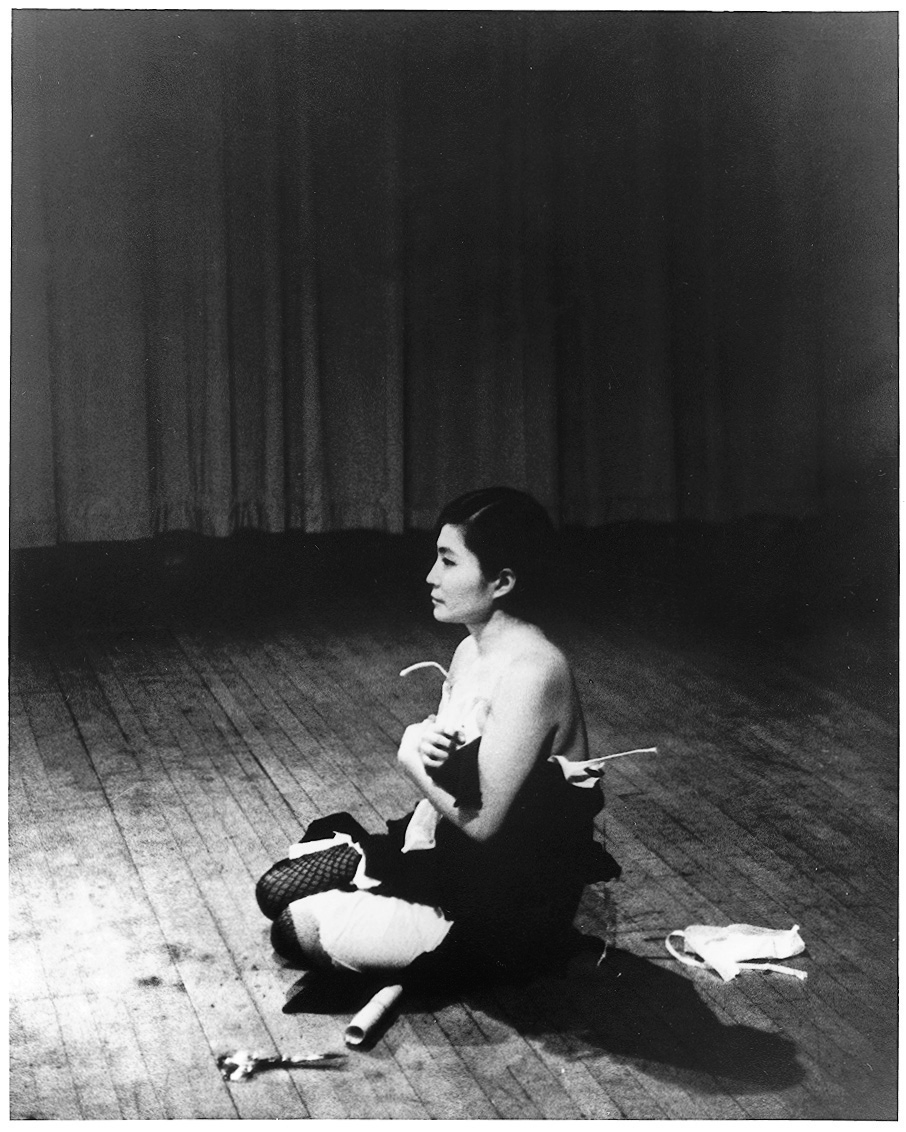

YO: Oh, you mean the Cut Piece [a video in which audience members are shown cutting off pieces of Ono’s clothes with a pair of scissors].

KG: When you did that, did you realize what a powerful sort of sexual, cultural image about women it was?

it is very important to me to do one thing a day that makes your heart dance. And if you can’t do that, to do one thing that would make somebody else’s heart dance. Yoko Ono

YO: Well, it’s kind of artistic narcissism, but when I get inspired with a piece I always think, “Wow! This is great!” But in those days I never thought that it would be experienced again later or be talked about. I always thought that my work was like improvisation: You do it and never look back. With Cut Piece, I did it once in Kyoto, the performance that you saw was in New York, and then I did it in London. All three audiences were very different.

KG: I heard the London one was kind of savage, cutting off all of your clothes.

YO: Well, savage was not the word I thought of. . . . but savage is right, too, actually. But there was also that kind of swinging London thing . . . so there was no inhibition. With New York, the sense of inhibition created a kind of space between each person coming up and cutting. So in terms of music, it was like there were pauses and it was beautiful. I think the New York performance was the most beautiful. At the time in New YorkI felt that-well, just like in Japan-it was still very hard for me to perform that work. You see that in the film. My expression is just like I’m trying to not have an expression . . . trying to be . . .

KG: . . . more like an object. It’s so powerful. It says a lot about . . .

YO: What was going on.

KG: And what’s going on now.

YO: It’s symbolic of what’s going on in society, in male society.

KG: People know so little about you . . .I was reading that in ’52 you were one of the first women in Japan admitted to study philosophy at a university, and you were really the first artist working in a popular music context, too.

YO: Have you heard Plastic Ono Band?

KG: Yes.

YO: Well, that was an excitement in itself. When I made that album, I felt like I was Madame Curie or something, discovering a new area. John was very excited for me, too, and we were just sort of holding hands saying, “Wow.” But then I got a photo of 20 fans in Japan holding a sign with an arrow pointing to a trash can that says yoko ono’s albums.

KG: Oh, my god. Do you think that if people knew you first as an artist, and could see what context you were coming from, they might have understood your music more?

YO: I don’t know.

KG: I think that that was a big confusion, because people in America generally aren’t that into art unless it’s really entertaining.

YO: Yeah, you’re right. It seemed that I just suddenly came up on the back of the famous John Lennon. And the thing is, it wasn’t that at all. It’s just that my musical and art careers, both of them were in very esoteric areas, you know? It was not for general consumption at all. So naturally people felt, “What is she doing?” From my point of view, it was a very exciting time.

KG: Do you think that since American culture is more interested in Eastern philosophy-which is the basis for so much of your work-that people have a better chance of understanding those ideas?

YO: It’s funny because the Japan Society show is the kind of thing that would have been laughed at, and it was-people didn’t even want to come to it in 1961. Now I think people feel more accepting.

KG: What do you say to yourself to help you deal with negativity?

YO: Well, it’s a very strange situation I’m living in, but it’s very interesting. I’m in a kind of isolation booth, an invisible isolation kind of thing. You can think of it as a shrine where you’re meditating, or you can think of it as a prison. Either way, it is true.

KG: I guess it gives you a certain freedom to be able to observe.

YO: Well, yeah. But that’s why I started to feel that it is very important to me to do one thing a day that makes your heart dance. And if you can’t do that, to do one thing that would make somebody else’s heart dance. It could be a very small thing like just looking up at the sky. Or it could be a very simple thank-you gift. If you keep doing that every day for a month or two, you’ll see that your life becomes totally different.

KG: I’ll try it.