Show & Tell

The Vibrant and Introspective Quilts of Rosie Lee Tompkins

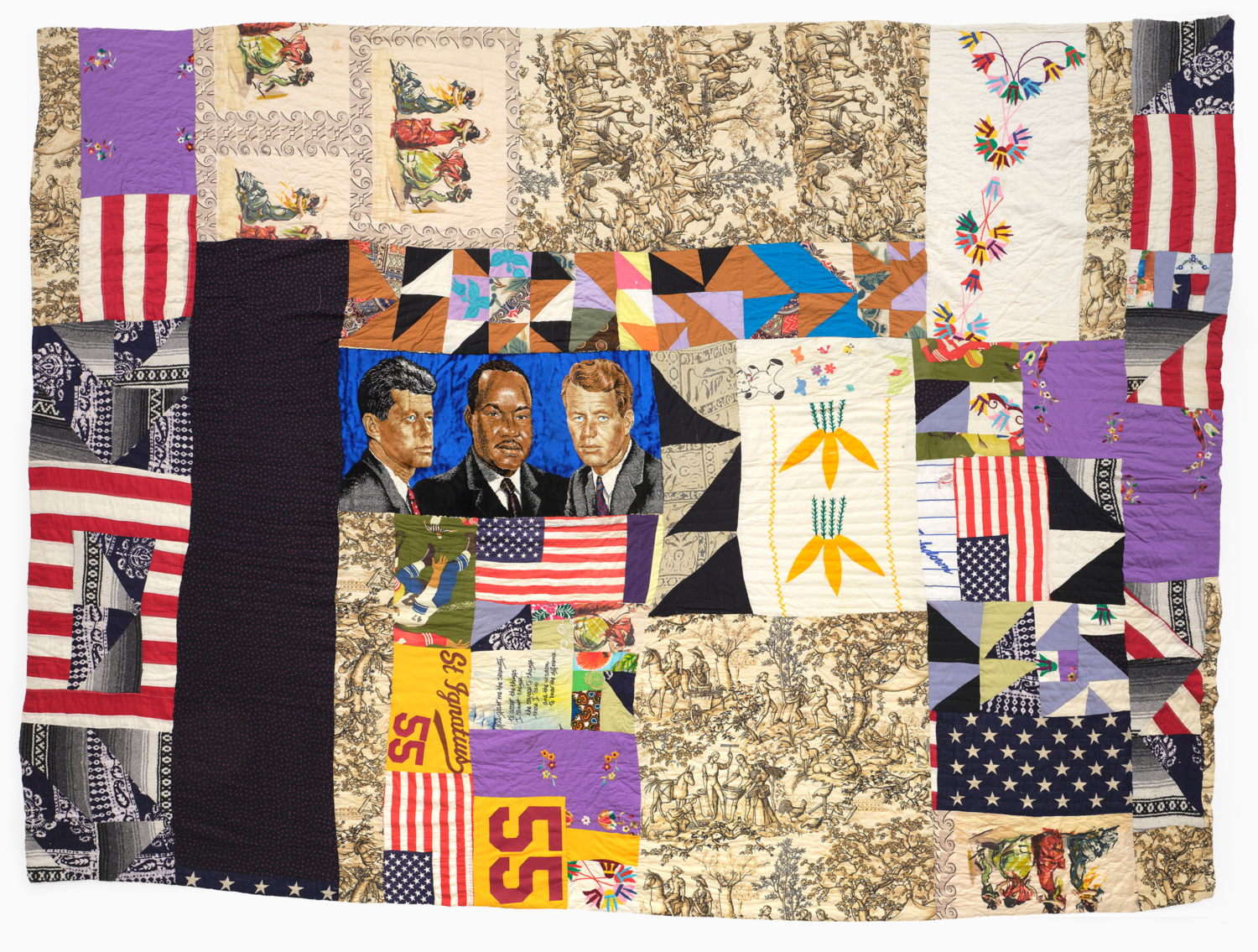

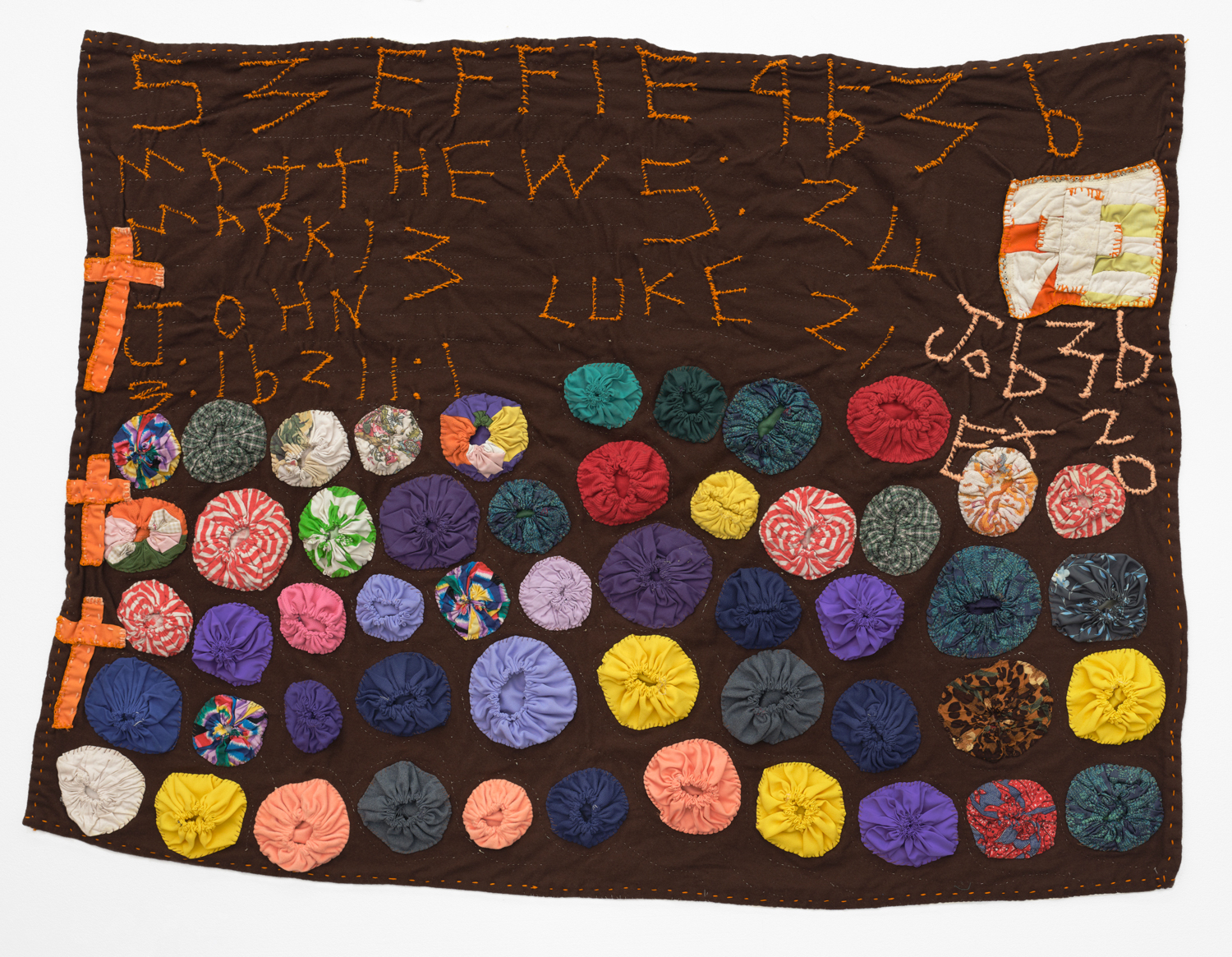

“Untitled,” 1996. All photos courtesy UC Berkeley Art Museum, Eli Leon Bequest.

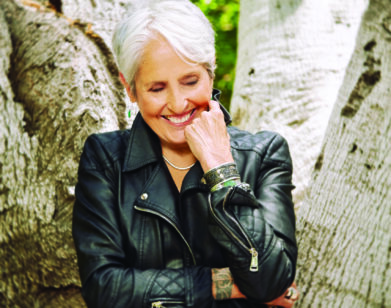

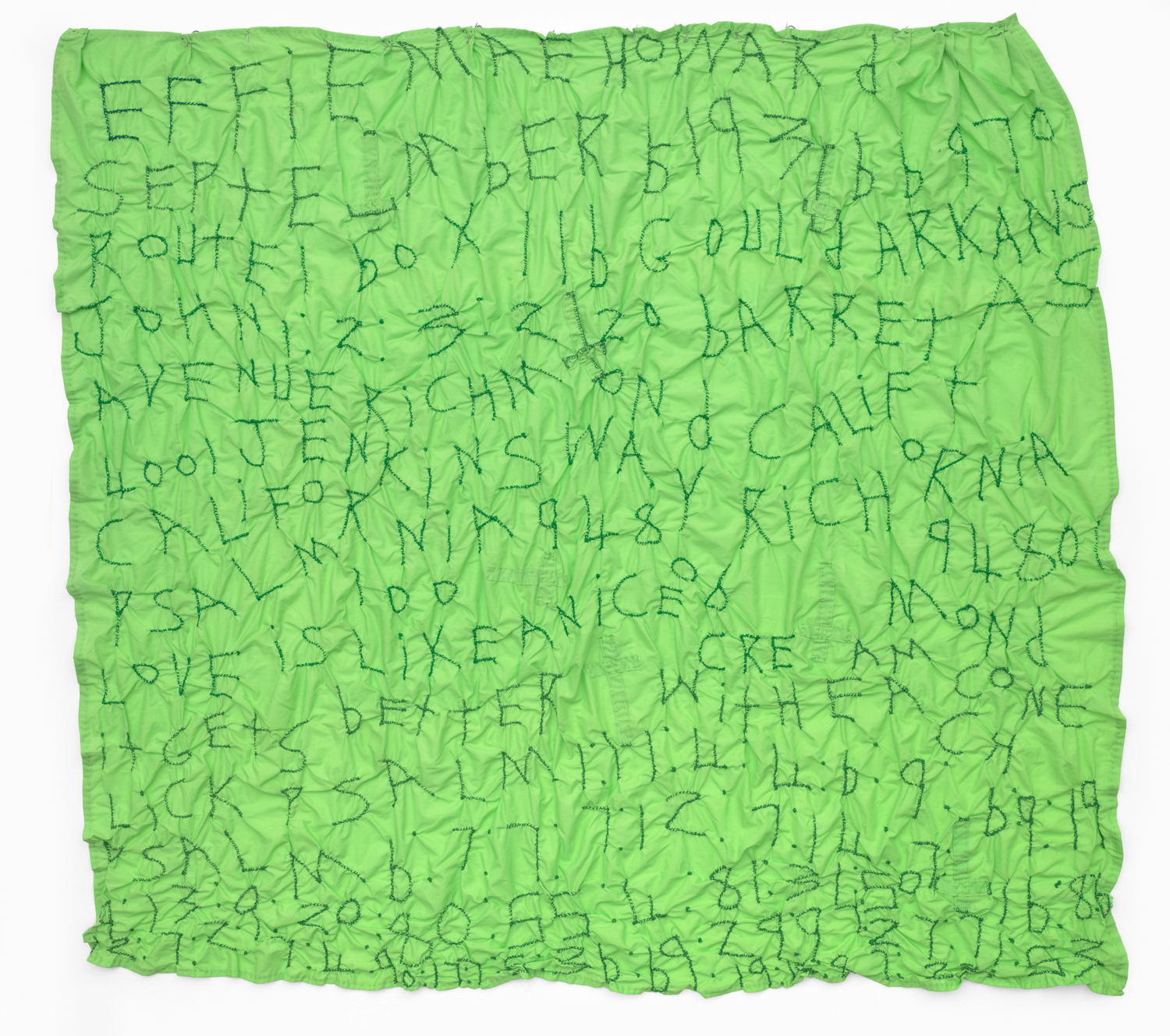

When looking at the work of the late master quilter Rosie Lee Tompkins, it’s easy to understand why her vibrant, multilayered fabric creations engender such reverence. Challenging the traditional notions of what a quilt could be or even look like, Tompkins’s painterly, improvisational designs seem to have more in common with jazz or contemporary collage than anything found in an Amish sewing room. Born in rural Arkansas and having spent most of her life in Richmond, California, before her death in 2006, Effie Mae Martin (who made art under the Tompkins pseudonym) genuinely believed that her creative process involved god directing her hands. The results were wildly expressive art objects crowded with embroidery, and stitched from found pieces of fabric such as velvet, reflective Lurex, fake fur, and the occasional dish towel or silk tie. Often these textiles would intentionally reference Black cultural iconography—from Martin Luther King Jr. to O.J. Simpson—all of which give her quilts an urgent, introspective reading, full of political, social, and spiritual resonance.

“Untitled,” circa 2002.

The recent visibility of Tompkins’s work is due almost entirely to the devotion of the Oakland-based collector Eli Leon. After a chance encounter with Tompkins in the early ’80s at a California flea market, Leon would spend the next three decades collecting and championing the work of the reclusive artist, eventually abandoning his psychology practice in favor of becoming a meticulous quilt collector and archivist. In 2019, Leon bequeathed his entire collection—nearly 3,000 pieces in total, with works by more than 400 artists—to the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Many of these pieces appear in its current exhibition, Rosie Lee Tompkins: A Retrospective, on view until December. The show, the artist’s largest and most comprehensive to date, features approximately 70 quilts, embroideries, assemblages, and decorated objects.

“Untitled,” circa 2004.

According to BAMPFA curator Lawrence Rinder, Tompkins’s work is indicative of a canon of fine-art quilters who are only beginning to get the recognition they deserve. “It’s a reminder that great art can be made out of anything,” he says. “Tompkins was just tapped into this creative inspiration that enabled her to put pieces of fabric together in ways that nobody had ever put them together before, and the end result is something beautiful. It is fresh. It’s emotional. What differentiates her from other quilters is that willingness to go beyond and to trust in the sheer power and energy that she felt flowing through her.”

This article appears in the September 2020 issue of Interview Magazine. Subscribe here.