Theaster Gates’ Monastic Orders

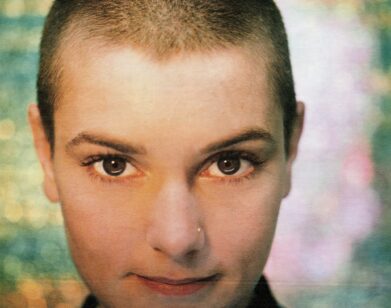

ABOVE: THEASTER GATES IN PERFORMANCE WITH THE BLACK MONKS OF MISSISSIPPI, 2012. PHOTO COURTESY OF KAVI GUPTA, CHICAGO | BERLIN.

A group of seven men recently completed a monastic retreat in Porto, Portugal, though not in the religious sense. They’re not even monks in the traditional sense—rather, they’re the musical ensemble The Black Monks of Mississippi, led by the Chicago-based artist Theaster Gates. Titled The Black Monastic, Gates and his group used the two-week residency-cum-retreat at the Serralves Foundation as an opportunity to further develop their practice. They performed 19 moves both in public and private throughout the vast grounds and gardens that are home to the Álvaro Siza-designed Serralves Museum and the Art Deco Serralves Villa. The various parts fused visual art with the participatory and the performative, experimenting with various senses.

“I think there are a lot of things in his practice that resonate with the situation here with respect to architecture, with respect to engagement with the community, with respect to the artisanal, which is very strong in Portugal, but also and fundamentally because of his practice,” said Serralves Museum director Suzanne Cotter. “It’s so performative, and the performative aspect of art-making is something that is a feature of the collection.”

With an improvised score that was deeply spiritual, soulful, and solemn, Gates and The Black Monks left an impact on the Serralves Foundation, culminating in a performance for some 600 guests, dressed in black tie at its annual gala dinner that marked the 25th anniversary of the foundation and the 15th anniversary of the museum. Cotter said that they have plans to use the material for a book, and a “bigger, more ambitious project.” Interview caught up with Gates to ask him about the monastic retreat, the Serralves Foundation, and how The Black Monastic responds to race and politics.

ANN BINLOT: Hi, how are you doing?

THEASTER GATES: I’m fantastic.

BINLOT: When did you arrive in Portugal?

GATES: I’ve been here for about 10 days now; maybe I’m on my ninth day.

BINLOT: How do you like it there?

GATES: This is my second trip. I came first to scout things out at the museum and look at their special collections and walk the grounds, and really try to get a feel for the place. I did that earlier this year in the spring and spent the last few months thinking of what the monks could do here to transform the space. It’s been great.

BINLOT: Why did you decide to do a “monastic retreat”?

GATES: In some ways I thought it would be a great opportunity for the Black Monks to get together outside of our normal presenting environments talk about what it means to have this ensemble, to live largely in the visual arts world and take cues from that. Also, we all have an interest in music so asking questions between the relationship between this secular, sacred music and the material world. It’s been our time to really learn from one another about our practices, but also to also use Serralves as a laboratory playing with performativity and musicianship and sacredness—monastic living. It’s been great.

BINLOT: How many are in the group?

GATES: There are seven of us performing.

BINLOT: Can you explain The Black Monastic for those who are not familiar with it?

GATES: It’s a term that I’ve created to suggest that there’s a way in which… All kinds of performance practices have a certain register of power or solemnity, and in some ways I wanted to give definition to this music that we’ve been making, and I think that the music is very much rooted in the music and the actions of black people—rooted in musical histories and the intensities of a particular Black American experience. But also on the monastic side, there’s a way in which artists across the world have been engaged in the question of simplicity, the minimal, the sacred, childlike, the natural, or a way of viewing nature, ways of responding. So I think this conflation of the Black Monastic is a way of thinking of the histories of black music and black performance in relationship with histories of minimalism, modernism, Buddhism, racism.

BINLOT: Speaking of that, you say it responds to the notions and histories of space within the nuanced contexts of race and the political sphere. How do you see it doing so?

GATES: I say it responds because I’m not a preacher, but I preach. I’m not a Buddhist, but I chant. I’m not race theorist, but I have questions and ponderances around the complexities of race and class and culture wherever I am—how those things play out wherever I am, so I think that the idea of responding is that Serralves, it has a set of interesting opportunities in—most of our time has been spent in their special collections. They have set of collections that are very different from say, my personal archive, and so how can the Black Monastic respond to that specificity of collection, so we’ve used Marcel Brodeur and Dan Graham and Mira Schendel as our launching pads, versus something else. I think using Joseph Beuys as a way of asking questions about the Black Monastic has been very compelling for us, very complicated; it complicates Beuys and also complicates the Black Monks, which has been great.

BINLOT: There are 19 moves in this performance piece. Can you describe a few of them?

GATES: One move was really just processing the grounds, just creating a procession and walking, and ultimately responding musically to this amazing 80-acre site. But then there were moments where we would identify things in special collections, like a work on paper by Dan Graham, and we turned that work on paper, which was a series of numbers, a piece that he did called Nominalism. We turned that numbers work into a chant. We invited two three-year-olds to create a body of work with us, with markers and paper, and we staged a temporary exhibition alongside the main exhibition space.

BINLOT: Who are the two three-year-olds? Were they strangers or did you know them?

GATES: They were just three-year-olds that were watching the performance with their parents, and Leonora and Levy were their names.

BINLOT: Are they twins?

GATES: No. They didn’t know each other, but they became part of our Monastic Order temporarily, making beautiful drawings that were then performed by our cellist, Khari Lemuel.

One of my favorites was to use the recording by Joseph Beuys. He has a recording that is simply, “jae jae nah nah nah,” and we played that in the gallery space, and then we all joined him in chanting, creating a temporary opera of Beuys’ basic chant with two double bases and three voices. A really beautiful piece. Joining a group of performers who were performing another artist’s work, I became the fourth performer in that work.

BINLOT: How do the grounds of the Serralves Foundation play a part in your performance?

GATES: It’s a very large site, it’s actually the front door to a beautiful Art Deco estate house, and the grounds were made for walking. There’s beautiful paths and vistas at every turn, and people throughout the week can often explore the grounds without coming inside the museum. The Monks thought that it would be fun if we just made the museum present by us being present performing what maybe looked like just a group of guys walking in procession one after another, but at best a group of monks on the vacation, taking in the rest of nature.

BINLOT: What were you guys wearing?

GATES: Normal clothes. No ambition for that. It was more in our actions, looking from the left to the right in a syncopated way, replicating hand gestures, walking in single file, having the kind of discipline to our strut, the Monastic strut, so it was more like it looked some fit dancers moving throughout the space as if we were professional monks.

BINLOT: A few of the moves were done without an audience watching. Did you record those in some manner?

GATES: No. I think that part of the monastic piece was having moments that were just for us or between us, and the objects we were involved with, or a kind of generative energy that belonged to the world and put good vibes in the museum. We do have a pretty ambitious camera crew that’s recording many things, but all the more reason to just have moments where we zone out and do our thing without the burden of recording.

BINLOT: How are viewers responding to this piece?

GATES: Yesterday we did a two-and-a-half hour performance in the atrium of the space where people first walk in, and that performance, it didn’t really have a beginning or an end. No song started, so people don’t always know when to clap or when to walk, or whether to join and participate, to really like that flexibility. It starts to feel less like entertainment-driven performance, and more just like we’re just practicing what we’re doing, and people can join, it’s like an ongoing conversation and that’s really great. And once people realize that we’re gone and we process away, you can hear applause, which is pretty nice too.

BINLOT: How do you think the country and the place affects your performance?

GATES: I think I’m passionately allowing myself to be influenced by the things that are around me with Serralves, where they’ve had such a commitment to collecting great artists and showing important exhibitions and having a very long and intimate engagement with artists. It just seemed like a great nod back to them to identify some of these great artists and see what they’re up to, and maybe wake them up in a way that they’ve never been awake before. I’d like to think that the monks are always making a newer form of music based on where we are. In this case, with Serralves, it was really a breakthrough for us—because not only were we performing with our instruments, we really got into the archives and the works on display as part of that, and that direct improvisational, and also researched influence was a lot of fun.

BINLOT: Yeah, I think it’s really interesting how you’re responding to their own collection, in a way you’re taking two pieces of art and creating something entirely new.

GATES: Yeah, I think very much in a tradition of well, all kinds of improvisation, it’s nice when there’s a kind of an object of improvisation—whether that’s a bit of poetry, or another musical piece that you’re responding to, but in this case it happened to be visual work, and sometimes, a language work done by visual artists. And it’s just been damn fun.

BINLOT: So you’ve been there for about 10 days now. Are you just working on this piece the whole time? How do you spend your days?

GATES: We have a regimen where we come to the museum at 10, we leave at 6, we eat at 8, we spend some time in conversation talking about what the work might feel like in the afternoon or evening—like tonight, we’ll have a performance at 10, so we’ll spend some time thinking about that performance and how to be successful. We don’t rehearse, we commit ourselves to improvising that work, so we’ve created some monastic rules, sometimes we follow, and sometimes we don’t.

BINLOT: What are they?

GATES: That we would listen to one another, that when we’re together we would look each other, that we would try to do things that we’ve never done before, we’d try to make others do things they’d not done before, that we would try to make secular things sacred, material things immaterial, and immaterial things concrete.

BINLOT: What do you hope to convey with The Black Monastic?

GATES: I don’t know. That to be monastic is personal, it’s a question, that there’s sacredness in seeing, and there’s sacredness in the everyday and that museums and art are much bigger and have the capacity to do more than that it would do given its stated missions. That when we think of a museum as a space, that is a particular sacred; we can regard art as something very high instead of something that is always cynical, always ironic, always sarcastic, always apolitical, that it could actually do things intentional and directive and sincere.

BINLOT: What’s next for you?

GATES: I’m still committed to some projects in Chicago, just lots of building right now. And I’m also thinking a lot about Picasso —particularly his African and oceanic collections, and the way that Modernism was influenced by what they call a primativist ethic. So I’m imagining Modernism as a naive art, and using it as the starting point for a new Modernism. Frieze is coming up, Miami Basel is coming up, one of the things I’m very excited about is that we’ve begun working with the Art Gallery of Ontario to imagine an exhibition that would happen in ’16, already that’s taking up a lot of my thinking. Just in terms of work, I’ve just had a tremendous amount of interest in architecture, and making works that are much more in the world than on a wall, but really about works of art that have an ambition, that need architecture, that takes the best of the history of a built environment and tries to do new things with it. It thinks about site-specific work that tries to do more. It thinks about land art, and then so this idea of thinking about DIA and its mission, Robert Smithson and his ideals, and then thinking blight in urban spaces, and could be blighted areas be the perfect locations for new, more ambitious works of art that are specific to a site.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE BLACK MONASTIC, VISIT SERRALVES’ WEBSITE.