New Again: Georg Baselitz

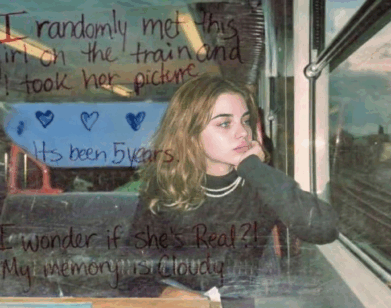

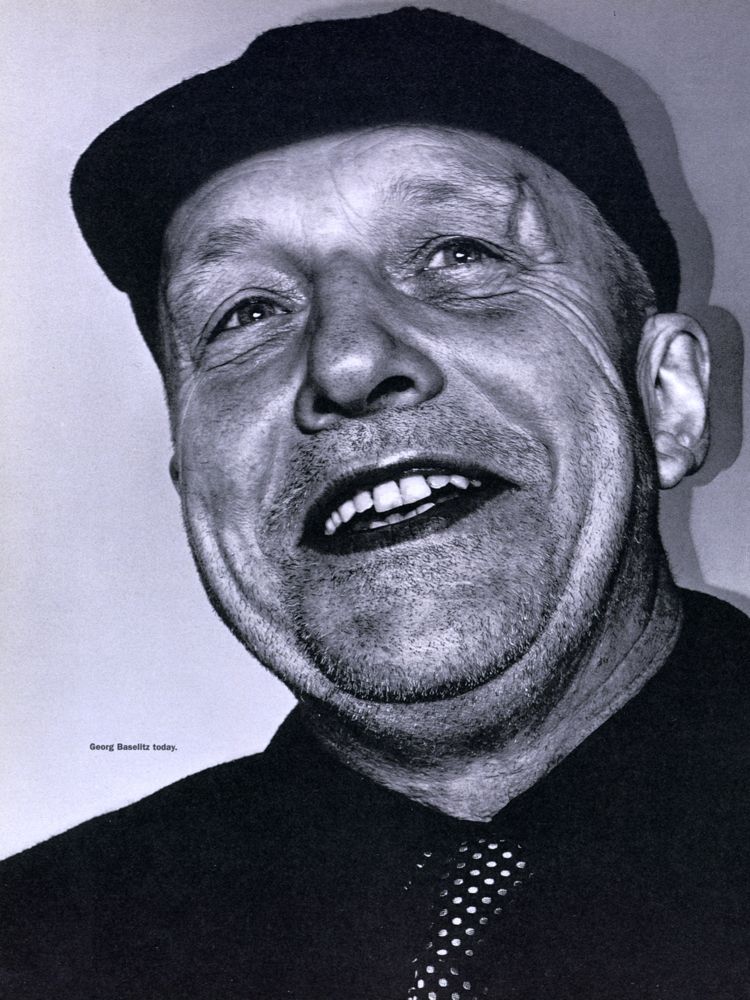

ABOVE: GEORG BASELITZ IN INTERVIEW, JUNE 1995. PORTRAIT BY RICHARD J. BURBRIDGE.

Georg Baselitz would like you to know that he embodies individualism. Rarely has another artist shirked categorization as surely and as vehemently as Baselitz. When we interviewed the German artist in June 1995, he was awaiting his very first retrospective exhibit on American soil at the Guggenheim. Now in his 70s, Baselitz hasn’t stopped creating, and his work has been exhibited in the US 105 times since then. Next week, on March 29th, Baselitz’s latest exhibition at the Gagosian in London will come to a close. Titled “Farewell Bill,” the show focuses on a series of upside-down, mirror-image, and perspective-jarring self-portraits, painted in bright strokes of color as homage to the late artist Willem de Kooning. The twin desires that Baselitz displayed to us in ’95—to be unpredictable and to shock—are clearly still at the forefront of his aesthetic ideology. Much of the chaos of Baselitz’s early paintings is still there, but they are both simpler and more complex in their characteristic distemper.—Kenzi Abou-Sabe

Raw Nerve Art

By Deborah Gimelson

As a German artist born during the time of Hitler’s Germany, Georg Baselitz has had to struggle with history itself to find his own way into history. He has taken the repression that came with the aftermath of the war and exploded it in his work. He is one of those artists who is essentially still unknown, even if his work is famous. The image of his work is imparted in the minds of all who have seen it, but the reasons for the work, and the man’s background, have not yet truly been discovered in this country. His retrospective, which just opened at the Guggenheim Museum, is one of the first real chances we’ve had in America to seriously discover what this tough, anxiety-producing art is really about. Here, in a two-part interview, an American art writer, Deborah Gimelson, takes on the heavyweight and finds out some of the answers and some of the mysteries.

Part One

Georg Baselitz seems almost too affable for a guy whose art—from eagles to men to dogs, much of it upside down—has torn through the fabric of traditional German painting and sculpture. His canvases and sculptures have managed to imprint their agitated, often tortured residue on the consciousness of contemporary art—a consciousness the artist is all too aware is not always accepting of his uncomfortable vision. His response to viewers finding his work ugly follows the line of reasoning he has adhered to from early in his career. If he is affecting someone so strongly and negatively, if they remember what they saw, says Baselitz, he must be doing something right.

After a successful, three-decade career on the Continent, Baselitz is having his first bona fide American retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, from May 26 through September 17. Although it appears to have taken a long time for a retrospective of his work to reach our shores, that is not the kind of problem that engages Baselitz, as he made clear in the interview that follows.

DEBORAH GIMELSON: I wish I spoke German, but I don’t. Can we try it in English, with translation, and see how it goes?

TRANSLATOR: Yes. O.K. [Editor’s Note: In the first part of this interview, conducted via telephone on March 22, the interpreter was Mr. Baselitz’s assistant, Detlev Gretenkort.]

GIMELSON: All right. Congratulations on the upcoming retrospective at the Guggenheim. You’ve had enormous success in Europe for many years, and I wonder why you think it took so long to have a show like this in America.

GEORG BASELITZ: I don’t have the feeling that it took such a long time.

GIMELSON: Even though we tend to give retrospectives to people in their thirties and forties in America?

BASELITZ: Lichtenstein was much older than I am when he got his first retrospective in Europe.

GIMELSON: [laughs] Uh-huh! O.K. What do you think the differences are between showing in Europe and showing in America?

BASELITZ: For me, America is a big unknown situation. I don’t see art as entertainment, so I don’t know exactly how to react.

GIMELSON: Because you don’t see art as entertainment? I don’t quite understand what you’re getting at. Do you think that American audiences view art as entertainment more than as art? Is that what you’re saying?

BASELITZ: Most of what comes from the States to Europe has something to do with entertainment. I can’t imagine artists in the United States having the same kind of isolated position that we have here in Europe. I have a feeling one lives more publically in the States.

GIMELSON: Hmmm. Anyway, I know you’re from Eastern Europe. I wonder what it meant to you to grow up in the postwar East. What kind of opportunities and what kind of obstacles were put in your path?

BASELITZ: When the war ended in 1945, the place that had been our home, which had been in the center of Germany, became and still remains a part of the Czechoslovakian border and the Polish border. I was seven years old. I grew up in the Eastern Zone, which became the German Democratic Republic in 1949.

GIMELSON: I’m trying to get at what it was like for you. In America there is, and has been, a resistance to German art of your postwar generation. I’m not so sure that this resistance only has to do with the idea of Nazism, which was happening while you were growing up. I think it also has a lot to do with the fact that certain kinds of art have been associated with fascism—for example, expressionism. You’ve been referred to as the greatest living neo-expressionist. How do you react to being called that?

BASELITZ: I became an artist because of the possibility it gave me to develop in another way, because I didn’t want to follow the same lines the others around me did. I was educated in the former German Democratic Republic, which meant that an individual figure had to be… like a soldier in the army, you know?

GIMELSON: Part of the bigger picture.

BASELITZ: Yes, part of the bigger picture. First, they tried for about a year to make me understand that I had to make a contribution to this system. Then after a year, they found out that I was too crazy for such things, and they dropped me out of school. [Gimelson laughs] So that was how I started at the Academy [of Fine and Applied Art] in East Berlin. Then I went to West Berlin and continued to study there.

GIMELSON: When did you go to West Berlin?

BASELITZ: That was in 1957. And there I found out that Germany is a kind of province. I didn’t know anything about expressionism, about the Bauhaus and Dada and surrealism. I was uneducated, so to speak—and everybody else was more or less uneducated, too. At the art school [the Academy of Fine Arts] in West Berlin, the great influences were coming from Paris. Those kinds of people didn’t exist anymore in Germany, because they had all gone into exile. I got sort of interested in this French thing, but I soon found out that existentialism was not congruent with my thinking. Then, in 1958 at the art school, there was a great American exhibition. It was a very big exhibition that was organized by MoMA [the Museum of Modern Art], with all these paintings by Pollock, Motherwell, and Rothko.

GIMELSON: The abstract expressionists.

BASELITZ: Yes. It was travelling all through Europe. It was the biggest and most powerful exhibition I had seen so far, and immediately I found out that even what I saw at this exhibition didn’t work for me, because I didn’t want to be colonized. So I forced myself to think about where I come from, and what has meaning for me.

GIMELSON: At that point, who did you identify with as an artist?

BASELITZ: I did not always trust my teachers, because I found them too weak. I was looking for something that could take me in a new direction, for things that I could admire. And because it was so hard to find this, I became a sort of outsider. That’s why I began to identify with the insane, “outsider” artists.

GIMELSON: The outsider artists in Germany, you mean?

BASELITZ: Not only in Germany, everywhere.

GIMELSON: Who were some of these people, specifically? Did they have names, or were they anonymous?

BASELITZ: Many of them were known, like Carl Fredrik Hill and August Strindberg, for example, and many others. There is a book that was written by Hans Prinzhorn and published in 1923 called The Artistry of the Mentally Ill, where you can find some of them.

GIMELSON: Ummm, all this is very interesting, but I want to get back to the subject of being a young artist for a minute. Do you have any contact with younger artists who are coming up today?

BASELITZ: Yes, I’m a professor at the art school in Berlin.

GIMELSON: And do you find that many of the obstacles you confronted as a young artist are similar to those that these young artists have to deal with today?

BASELITZ: I have always been aware of different movements and directions in art. But, in general, I’m always bored by any kind of generalization when it comes to artists. I think that there are just single individuals, who are valuable, and they work outside of any group.

GIMELSON: You mean those who develop as great artists.

BASELITZ: Yes.

GIMELSON: In some circles you’re well-known as a collector of African art. I wonder how those images, or that primordial energy from them, filter into your work. Can you describe the transaction between the two things, your collecting and your own work, and why collecting is so important to you as an artist?

BASELITZ: I have always had the feeling that other people are too stupid to discover interesting things. That’s why I do it myself. I think of collecting as a way to show that I understand what’s important better than others do.

GIMELSON: How many pieces are in your collection?

BASELITZ: Oh, I have collected so many different things.

GIMELSON: I’m sure, and for many years, right?

BASELITZ: Yes. At first, I started collecting my artist friends, artists like myself who nobody had yet noticed. I believe that I was the first to collect the very early [A.R.] Penck paintings. In everything, all I am collecting, so to speak, are my friends—artist friends. Right now, I’m focusing on African sculptures more or less from the Congo area. I’m also collecting 16th-century prints from the Ecole de Fontainebleau. Nowhere in my collection do I, say, have a Renoir painting. Because everybody knows that this is a good painter without me having to demonstrate it.

GIMELSON: I’d like to talk now about some people who have been intricately involved in your career. You met Michael Werner [who has continuously represented Baselitz since the beginning of the artist’s career and was influential in introducing his work to America] very early on. I’d like to know what the atmosphere was like in German art circles at that time, and what you think you and Werner saw in each other to forge such a strong and long-term association.

BASELITZ: We were from the same generation and the same nationality. Nobody had one penny in their pocket then. It was a very difficult time, economically speaking. When Werner saw a painting of mine, such as Die grosse Nacht im Eimer [“Big Night Down the Drain” 1962-1963], which back then nobody wanted and everybody thought was ridiculous, he realized that this was the right provocation, that it represented the feeling of the times in the right way.

GIMELSON: Do you have any specific stories about how you and Michael worked together?

BASELITZ: Michael was the first person I worked with who had something to do with art dealing. This was in the early ’60s. I remember that Michael told me about a famous collector, and Michael set up an appointment for us to meet. This man looked around the room and at my pictures. Then he said, “Young man, why are you doing these horrible things? Look out the window. There are nice girls out there. It’s springtime. Look at how beautiful the world can be. You’ll ruin your health by smoking so much and doing such tortured things.” The he left, embarrassed, without buying anything. And half an hour later, Werner came over, and I told him what had just happened. We agreed that this meeting had been a success.

GIMELSON: What do you feel is the absolute best situation, the optimal physical structure, for your work to be seen in?

BASELITZ: If my images stick in peoples’ heads, if they know the image without even looking at the image.

GIMELSON: Well, we should probably stop for now, since we have a second meeting for this interview in person when you come to New York next week. You know, I’ve seen you in Berlin a couple of times. You winked at me on the street once. [to the translator] Don’t tell him that! [translator tells Baselitz]

BASELITZ: On what occasion?

GIMELSON: The “Metropolis” exhibition four years ago.

BASELITZ: Are you sure it wasn’t somebody else? Because I don’t have a beard any longer.

GIMELSON: No, it was you. See you on Monday.

Part two

Curious to see what the dynamic of the artist who has made so many dynamic images is like in person, I sat down with Baselitz face-to-face in Interview‘s wood-paneled library to resume our talk. Baselitz drank espresso doppio and sometimes got up between translations of his responses to look at the selection of books on the library shelves; the first thing he did was make sure there was something about Baselitz on the shelves. Dressed in a well-made, wide-wale dark blue corduroy suit, dark shirt, and expensive silk tie, his current image is hard to reconcile with the Baselitz who reputedly, in his youth, hung out in Berlin bars with the Baader-Meinhof terrorists. Now more country squire than social revolutionary (he spends most of his time in a castle in Derneburg, where his studio is in a series of connecting, high-ceilinged, 17th-century rooms), he still wages an aesthetic war with his stark, volatile, and often primitive images. [Editor’s note: The following interview took place on March 27 in the Interview library. On this occasion, the interpreter was Waltraud Raninger, a translator who works with the Guggenheim Museum SoHo.]

GIMELSON: I want to begin this part of the interview by asking you about Francis Bacon. Now that Bacon is dead, many people consider you the most important artist of senior stature working in Europe today. How do you feel about this?

BASELITZ: I don’t know who made up this sort of greatest-hits list for artists. If one artist isn’t moving forward anymore, then it’s assumed another one is going to take their place. With Bacon’s death, a whole genre of art died. Does that mean now that I’m the next one to die?

GIMELSON: [laughs] I hope not.

BASELITZ: So do I.

GIMELSON: Can you talk a little bit about what you think neo-expressionism, a term that has often been used to describe your work, means in Europe, and what it means in America, and how the two notions of this genre differ?

BASELITZ: First of all, I am not a representative of anything. When art historians or critics or the public put somebody in a drawer like this, it has a tranquilizing, paralyzing effect. Artists are individuals. They have ideas, and the conventions for one’s self as an individual are not for a group. There are always those who follow the group, but they belong in the margins. I refuse to be placed within, or added to, one particular school.

GIMELSON: Why do you think it is then that people have tried to slot you into that neo-expressionist mold?

BASELITZ: I don’t know. When I began as an artist, I already did not like expressionism, or abstract expressionism, because abstract painting had already been done. I did not want to belong to any one group or the other, and I’m not one or the other.

GIMELSON: Where do you think the main impetus was coming from in your work when you were in your twenties, as opposed to now, when you’re in your fifties? What were the forces working on you then, and the obsessions, and what’s different about them now?

BASELITZ: These forces are biologically different now than they were then. In the beginning, the energy involved to create came from my reaction to the work of other artists. The force behind this was aggression. The art that I saw was great, but I had to reject it, because I could not continue in the same direction. So I had to do something entirely different. It had to be so different, so extreme, that those who loved pop art, for instance, hated me. And this was my strength. Later, it again worked in a biological manner. But in no way was it just my reactions against things.

GIMELSON: I am wondering how you would like this exhibition at the Guggenheim to represent your work.

BASELITZ: In a place like the Guggenheim, I would like to be a representative of arte povera. This would be my ideal. Unfortunately, God had something else in mind. I’m a painter, and this space is completely inappropriate for my work. But in the end, maybe this is also an advantage, because we have seen so many exhibits in recent years where the exhibition design was aesthetically beautiful. In this case, if someone wants to get something out of the exhibit, they must neglect the aesthetics and look at my pictures.

But I do not have a philosophy about retrospectives. Of course, I cannot change what I have done. What I am doing today, this I can change, in view of whatever I have done before. My retrospectives are like a series of ghosts. And for me to see my work collected like this is like entering a haunted house.

GIMELSON: You have spent your career defying tradition and structure, constantly remaking yourself or your art through your various paintings and sculptures. Yet in other aspects of your life, traditional structures, like family, are very important. Can you talk about this?

BASELITZ: As a human being, I am a citizen, but as an artist, I am asocial. A citizen sticks to conventions, does whatever is social. Artists, of course, must reject all conventions. I see no differently in reconciling the best of both of these worlds.

GIMELSON: If you met somebody who’s never heard of you or seen your work, how would you describe what you do every day?

BASELITZ: I would say I am somebody who builds furniture like a carpenter with canvas and color. No, I would say I build buildings or houses like a bricklayer with canvas and paint. This is a very good question.

THIS ARTICLE INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE JUNE 1995 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.