The radically reworked perceptions of multimedia artist Dan Graham

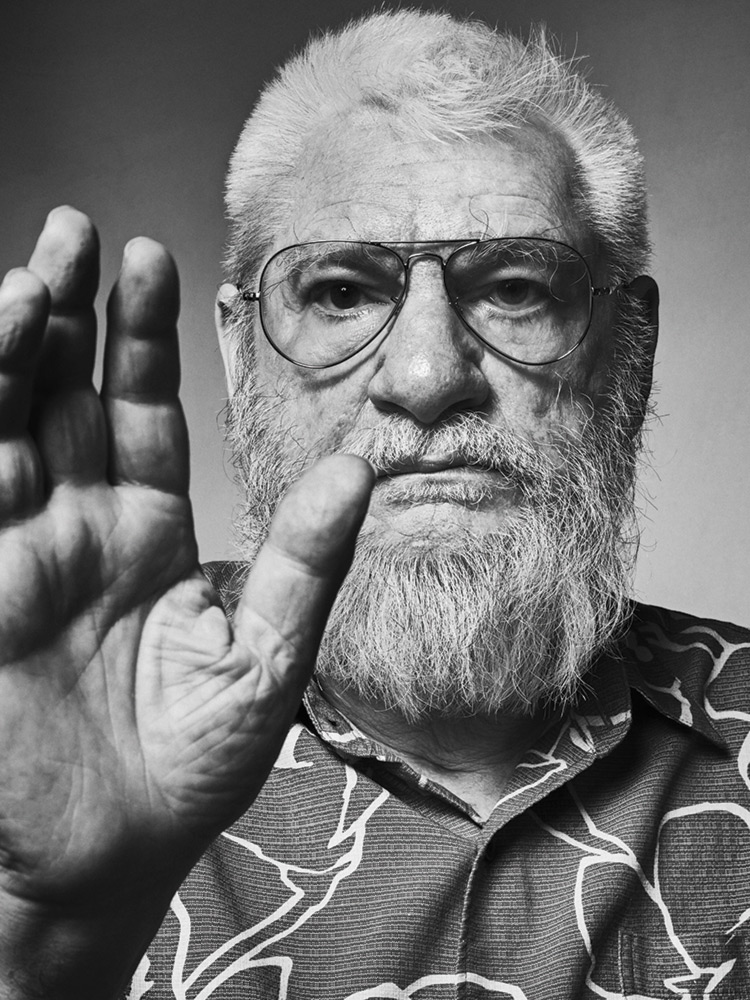

Since the late 1990s, the artist Dan Graham has worked out of his loft in Nolita, a New York neighborhood that has undergone extensive gentrification over the last two decades. On a recent visit, I spotted a pop-up skateboard-and-backpack store teeming with young shoppers a few steps from Graham’s door. Maybe Graham likes it this way, as he’s written so much on rock music and youth culture, and has even designed public structures for children. You never know what his frenetic mind is going to latch on to next. Whether it’s a spontaneous evocation of David Koresh and Waco during a quiet walk through Donald Judd’s Marfa compound; bringing up an anecdote at the most inappropriate moment; or his amazing, almost encyclopedic recall of information that would give most savants a run for their money, Graham, now 75, never ceases to surprise.

He’s deeply into astrology. Anyone who meets him almost always enters into his constellation of astrological annotations. He’s an Aries, indicating spontaneity. He’s also into clichés, architecture, music, art, puppets, mixtapes, and TV comedy. I’ve known Graham since the mid-’80s, when the art world was a much smaller place. Today, of course, most people know Graham as an icon, the quintessential hybrid artist whose practice has encompassed a range of media, disciplines, and contexts, including video art (of which he was an early pioneer), architecture, performance, photography, literature, and most notably, a series of steel-and-glass pavilions. This past summer, one such pavilion, Child’s Play (2015–16), went on display in the sculpture garden at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. In spite of all that, Graham occasionally insists his work will be forgotten and that no one wants his archive.

His anxiety is understandable. The past couple of years have been intense ones for a man with so much spirit. A seizure while on a site visit in Philadelphia put him in the hospital for months, and it was touch-and-go for a while. But now Graham is back, home with his wife, the artist Mieko Meguro, and doing well—busy with rehab, overseeing operations of his studio, and thinking about the possible uses of television, a favorite subject of his, for a series of future works.

MICHAEL SMITH: Okay, Dan. Let’s start with your childhood in New Jersey.

DAN GRAHAM: I remember being fascinated by this cartoon show on TV, with Uncle Fred. I was utterly fascinated by how TV was produced. Uncle Fred not only showed cartoons, he was also a ventriloquist. I saw that the puppet could be worked mechanically. Later, there was Howdy Doody with its Peanut Gallery. I liked how these shows integrated the spectator—in other words, the studio audience—and how that interaction became part of how the whole thing worked.

SMITH: We had Howdy Doody growing up in Chicago, but not Uncle Fred.

GRAHAM: It was on a local station in Newark. I knew that I’d have to understand the medium of television much better after watching Uncle Fred for my career. By the way, what I really love is Canadian humor.

SMITH: Didn’t you go on a family trip to Canada when you were a kid?

GRAHAM: Yes. Nova Scotia was unbelievably good. It’s a little bit like Scotland. They had bagpipes there. But that family trip was a little traumatic. I was thrown out of the car for arguing with my father.

SMITH: Thrown out of the car?

GRAHAM: I think my father gave me an ultimatum. So, actually, I got out of the car. I had a very troubled childhood.

SMITH: Until what age?

GRAHAM: Until I decided I would stay with a friend in the East Village in New York.

SMITH: How old were you then?

GRAHAM: Around 13 years old. But I was never on the streets. I never smoked dope. In fact, my first impressions of New York City were of when my mother took me to Gimbels to buy stamps.

SMITH: I assume you finished high school in Jersey?

GRAHAM: Honestly, I wanted to drop out. I was bad in all my classes—actually, I did very well in English.

SMITH: I would imagine, because you’re a great writer.

GRAHAM: Thank you. I had a very good English teacher in school named Mr. Donnelly. He was a kind of freethinking semi-intellectual. He allowed

all the kids to make out in his classes.

SMITH: Excuse me?

GRAHAM: It was called “petting” back then. I later learned what that word meant from the Beach Boys album Pet Sounds.

SMITH: Did you finish high school?

GRAHAM: Yes, I never actually dropped out. I’m fuzzy about that time, though, because I almost had a schizophrenic breakdown, and they decided to give me Thorazine. I stopped taking it because it was making me feel too weird. That’s when I started reading science fiction instead.

SMITH: That’s an interesting pathway to science fiction.

GRAHAM: Oh, here’s another thing about my childhood: I was a paperboy. I remember I went to collect the money, and I noticed one of the housewives was watching Liberace. I never knew that Liberace’s best friend was Elvis. They both apparently were mama’s boys and Liberace took Elvis under his wing and taught him how to dress for Las Vegas.

SMITH: Did you ever go to Graceland?

GRAHAM: No, the furthest South we ever went when I was a kid was Kentucky. I think the Everly Brothers were from Kentucky. It was totally wild there. Everyone was playing rock ’n’ roll on the radio. I really got into it. Of course, we had Alan Freed on the radio when I was a kid. He was from Ohio.

SMITH: Let’s go back to TV, since some of your work reflects television and the suburbs. What sitcoms did you watch?

GRAHAM: I want to go back a little earlier and stay on the subject of radio. I wasn’t intellectual enough to understand Ernie Kovacs at the time, who did radio before he did TV, but someone told me he was the

founder of video art.

SMITH: I read somewhere that Kovacs was the historical link to William Wegman. Since you’re a fan of Wegman’s, Kovacs should come easy to you.

GRAHAM: I’ve been trying to do a trade with Wegman for a long time. I just don’t know what to take because they’re all good. The reason I like him is because he thinks everything is funny and on the edge of being offensive. One of my favorite works of his is not a drawing or a photograph. I gave a talk once at UCSD, and I looked around at their outdoor project collection. Wegman did a project that was like one of those overlooks where you drive the car for scenic views. The boundary was made of stone, and there was a telescope aimed at a fake rendition of the Salt Lake City Mormon Temple. I guess it also appealed to me because I had a telescope club. I built a telescope with my dad when I was 13 years old. I was very shy around girls. Normally, my father and I didn’t get along, but he helped me assemble a telescope from a kit. I showed all the boys and girls the planets. I kind of lectured about the planets.

SMITH: Perhaps that was your introduction to astrology.

GRAHAM: Well, I did take some students to the Princeton observatory. That was the beginning of my teaching experience. Men always use optics. It probably goes back to when I had a magnifying glass and killed ants. Ants remind me very much of Martians.

SMITH: Sci-fi seems to have figured prominently in your life.

GRAHAM: I guess because it was aimed at my age group, which was 12- and 13-year-olds, and to kids who think they know a lot about science. My hero was Einstein. But then I discovered [the German physicist Werner] Heisenberg, who I thought was better than Einstein. There was also a magazine called Astounding Science Fiction. The editor was named John Campbell. A friend and I visited him in Mountainside, New Jersey, near the cutting-edge technology institute Bell Labs.

SMITH: Didn’t Bell Labs do E.A.T.? [Beginning in the ’60s, Bell Labs researchers collaborated with artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage on tech-centered art projects under the auspices of Experiments in Art and Technology.]

GRAHAM: Yeah, Bell Labs came out of telephones and went into a lot of other things. Anyway, for us to meet an editor of a great science fiction magazine was thrilling. But he lived in a drab suburban home and was wheezing all the time. I guess he had asthma. I realized then that maybe science fiction writers were actually kind of semi-creeps. Later, when I was interested in art, all the artists I knew would go to paperback stores and read a bit of science, particularly the so-called minimal artists. Carl Andre subscribed to Scientific American as did Lee Lozano. I think a group of British science fiction writers, like Brian Aldiss and

Michael Moorcock, were doing a lot of LSD, and they had a lot of time paradoxes. A piece of mine, Past Future Split Attention [1972], owed a lot to Cryptozoic! by Brian Aldiss, about time going backward.

SMITH: There were two performers in Past Future Split Attention, one predicting the other’s movements in a continuous feedback/feed-ahead loop. I always liked the pieces where you appeared as a performer. I’m thinking, in particular, of Performer/Audience/Mirror [a 1975 video-documented work in which Graham performs for an audience in front of a mirror].

GRAHAM: I didn’t want to use myself as a performer. I was interested in the spectator.

SMITH: Well, what about the piece where you’re naked with a woman in a cylinder, both of you holding cameras?

GRAHAM: Oh, that was a publicity shot. I refused to be in the actual film [Body Press, 1970–72, two films projected on opposite walls].

SMITH: You got naked for the publicity shot? Who was in the film?

GRAHAM: The male in that film was a boyfriend of Bernadette Mayer, Vito Acconci’s collaborator. I was directing it. The photo was picked up later by the internet. Now, you mentioned Performer/Audience/Mirror. That was originally a slight attack on Joseph Beuys, who was a guru performer.

SMITH: An attack on Beuys?

GRAHAM: He was doing performance in New York. I guess the community was suspicious of him. He was German, he was political—maybe it had something to do with Nazism. In Performer/Audience/Mirror, I was like a political figure, as Beuys was. When you define the audience, the performer becomes what the audience wants. Politicians do that all the time.

SMITH: My fantasy is to redo that piece with you, somehow.

GRAHAM: What I like about the piece is that feeling of the amateur. But neither of us are amateurs anymore.

SMITH: I was thinking about Acconci’s whole practice in relationship to yours. He talked about transitioning from writing to performing, moving from the space of the page to the space of performance. I am curious if this is also true in your work.

GRAHAM: Vito used to call me up and say, “Dan, I have no ideas. Give me some ideas.”

SMITH: And did you?

GRAHAM: To a certain extent. But when he got into architecture, he didn’t know what the hell he was talking about. See, my understanding of architecture is when you actually go inside and experience it.

SMITH: He was a great performer.

GRAHAM: Seedbed is quite good. I think he was a man of theater.

SMITH: Can we talk about TV and sitcoms now?

GRAHAM: I didn’t see many sitcoms. I remember Robert Cummings [star of the The Bob Cummings Show, among other sitcoms]. He was a very ’50s white guy who was always making mistakes. He was very much like this music group, the Four Freshmen, who influenced the Beach Boys.

SMITH: The Beach Boys represented everything I knew I’d never have. The world that Brian Wilson constructed intimidated me.

GRAHAM: When I was compiling Dan Graham’s Greatest Hits [Graham’s mixtape series, which has now run to six volumes], I remembered “Add Some Music to Your Day” by the Beach Boys, which almost sounds like a commercial. It’s absolutely brilliant. The form comes very close to a simple advertising slogan. Brian Wilson was extremely original, but he also stole a lot from Jan and Dean. What interests me, as a Jewish fellow, is the kind of white Protestant church music you can hear in the rock of the time. Many people came out West to California from the Northeast and got very into Protestant hymns. That is the voice of Karen Carpenter—totally white, with a strange kind of spirituality that is actually hard to understand. Also, utter naïveté. All the Beach Boys songs are about how we can get married and be happy—a kind of ’50s dream. The group I was very close to, because I am a New Jersey boy, is the Four Seasons.

SMITH: I want to leave the Garden State and ask you about New York City. Could you talk about your gallery, John Daniels, which was up on East 64th Street? You were really young when it opened in 1964. It seemed very ambitious.

GRAHAM: That’s a bit of a myth. I was what they call a slacker. I had no job, and I had two friends who wanted to social climb because they were reading Esquire magazine, and a gallery looked like a cool place to social climb. They put in some money and my parents put in some money as a tax loss. I knew nothing about art.

SMITH: And the artists you brought in just thought, “Okay, well … why not?”

GRAHAM: No. The first show I did was a Christmas show where anybody who came in could exhibit.

SMITH: An open call?

GRAHAM: I don’t think I advertised. The artist I bonded most closely with was Sol LeWitt. He wanted desperately to have a gallery because he was not in the Green Gallery, where all his friends were. The reason I liked Sol LeWitt is that we had the same favorite writer, Michel Butor. And [Donald] Judd liked Alain Robbe-Grillet. We were all reading French novels and watching Godard films. People who came to the gallery were young artists who wanted to make it. So they would find any gallery they could that wanted to show them.

SMITH: You were showing incredibly cutting-edge artists, but you make it sound like another telescope club.

GRAHAM: Well, I didn’t even know what was going on. All I know is that we all wanted to be writers. Other shows there were group shows. One was called “Plastics.” We had a Judd plastic piece and a [Robert] Smithson.

SMITH: It’s funny how these artists were gravitating to you.

GRAHAM: I think artists were looking for galleries.

SMITH: It’s no different today.

GRAHAM: The personalities were very different. There was even a period a bit later where artists wanted to destroy value.

SMITH: Speaking of value, how was business?

GRAHAM: We hardly ever sold any work. We went out of business at the end of the season. Afterward, I did small jobs. I was very good at lighting.

SMITH: You were an electrician?

GRAHAM: No, the lighting was for installations for art shows. That’s part of doing a show. I was also briefly knocking down walls in Roy Lichtenstein’s studio.

SMITH: Are you speaking metaphorically?

GRAHAM: No, that’s all I did. I wasn’t very good at it. Lichtenstein impressed me enormously. He was shy, a workaholic, and I could detect he was interested in a kind of Jewish sense of irony.

SMITH: I imagine his use of clichés also made an impression. Pop artists really put cliché in people’s faces. Allan Kaprow wrote about America’s attraction to melodrama.

GRAHAM: About four years ago I saw a show of artists in New Jersey at Princeton University. I realized Kaprow was, like me, also taking photographs on highways. At that show, there were some big surprises. There could be a great little documentary on how all of these artists were teaching at terrible schools, then went to Rutgers and discovered each other.

SMITH: Speaking of clichés, what’s the deal with astrology?

GRAHAM: I think astrology was important to me when I was teaching. It allows you to create a bond with students very quickly. “What’s your sign? What’s your birthday?”

SMITH: I really liked your Architecture/Astrology book [a collection of astrology-informed analyses of artists and architects, co-authored with Jessica Russell, with illustrations by Mieko Meguro]. Now, I want to ask you about your pavilion, Child’s Play, which was recently installed in the sculpture garden at MoMA. Is that title a comment on sculpture, or do you actually think of it as a place for children to play in?

GRAHAM: When I pitch my work, I say, “These are fun houses for children and photo opportunities for parents.”

SMITH: It doesn’t look at all childproof.

GRAHAM: I made sure that the framework was rounded.

SMITH: I was very impressed when I got the invitation to the opening last summer. Not long before that, you were in the hospital recovering from a very serious illness. And only a week or two before that, you were going on about how no one is interested in your work.

GRAHAM: First of all, it took a while to make happen. It’s very bureaucratic there.

SMITH: So, a few years ago they said, “We’d like to purchase—”

GRAHAM: No. Ann Temkin [MoMA’s chief curator of painting and sculpture] asked me to do a piece. She’s a Capricorn, so I talked to her about that. I told her that because I’m Capricorn ascendant, I’m becoming more like a Capricorn. One thing I didn’t realize—I should have—is that the location of the sculpture garden is great because you can see all the glass office buildings.

SMITH: A friend told me about a romantic moment with a girlfriend in your pavilion when it was on display at the Walker [Two-way Mirror Punched Steel Hedge Labyrinth, 1994.96]. They played with their reflections, as their faces merged and disappeared. Later that day they went their separate ways. I’d think the old MoMA sculpture garden would have been more conducive for those kinds of connections.

GRAHAM: I think that work has to be in relationship to corporate buildings, because it’s basically a corporate situation. My work is not a sociological critique of alienation; it’s the opposite. Maybe people misunderstand it that way.

SMITH: I still liked the old MoMA sculpture garden. It was much more intimate. I do want to mention you were in rare form at your opening there. You really turned some heads when the microphone was handed over to you, and you started your speech by saying that your favorite museum is the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. I was not expecting toastmasters [Graham laughs], but to be honest, I did not expect that.