IN CONVERSATION

Sayre Gomez and Jonas Wood On Poker, Parenthood, and Paleontology

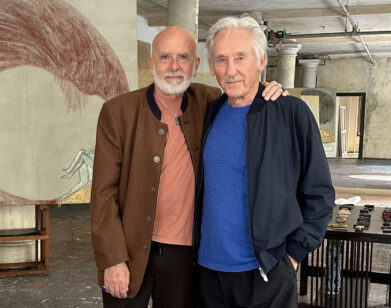

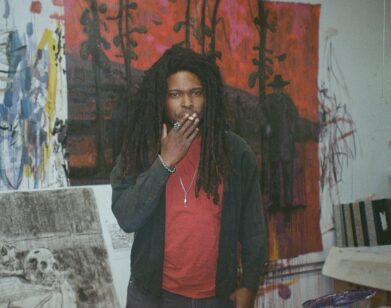

Sayre Gomez, photographed by Jonas Wood.

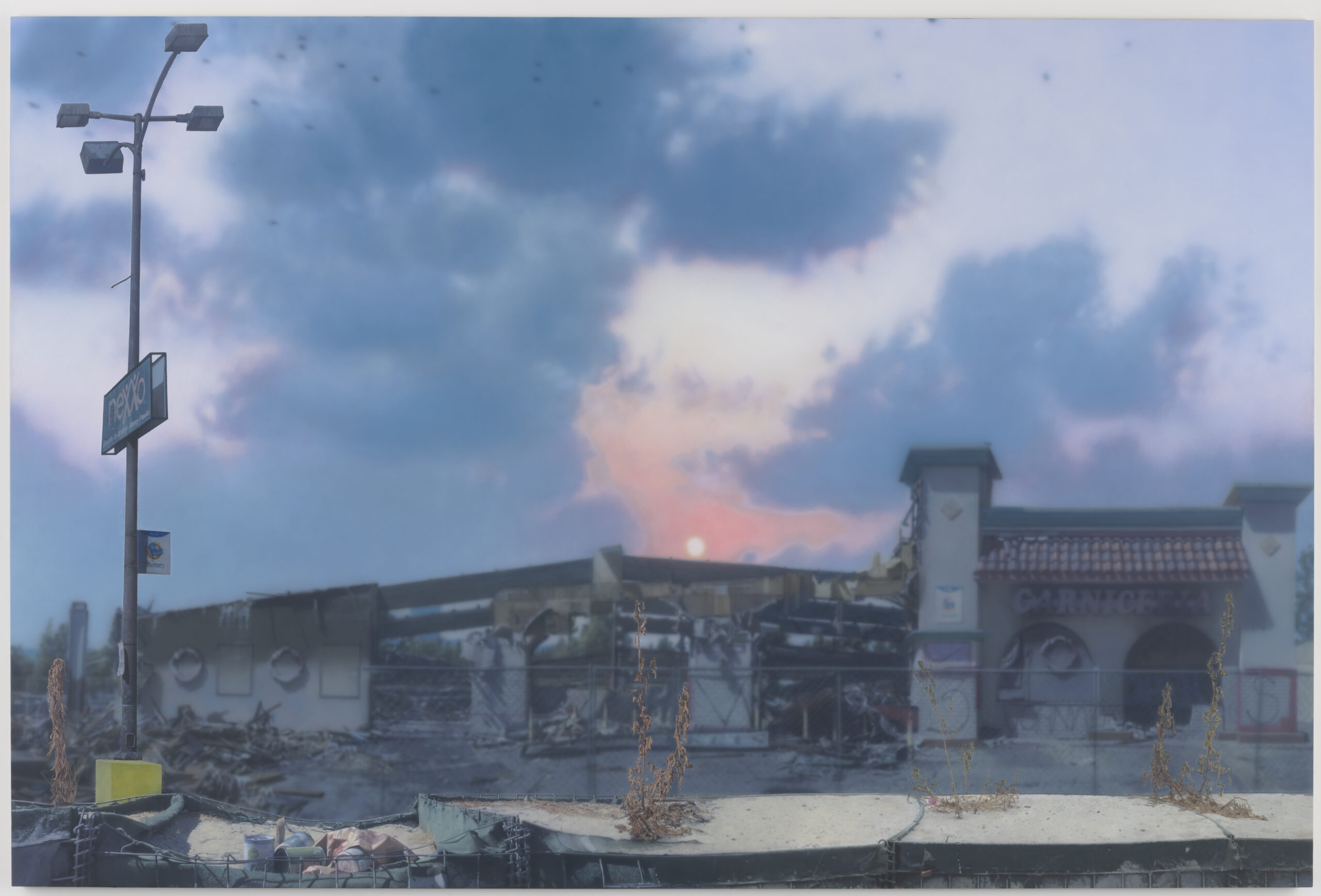

Currently on view at The Broad is Desire, Knowledge, and Hope (with Smog), a group show presenting work from artists across different generations who have responded to the development and decay of Los Angeles over the years. One of them is the painter and multimedia artist Sayre Gomez, whose contributions to the show include a dystopian projection of the angel city, where an incinerated strip mall glows under the setting sun. But the second painting is a diptych of neon sign for a nail salon, highlighting the vibrancy and vitality of local commerce. Last week at his studio, he told his friend and fellow artist Jonas Wood, whose work is also in the show, how his feelings about the L.A. have changed since having kids. “My work’s actually gotten darker since having kids because it just makes me think about more shit,” Gomez explained. “They’re like, this catastrophic lens.” In conversation, after Wood got in a few puffs of grass, the two chatted about L.A.’s recent contemporary arts explosion, the 2000s poker boom, and Sayre’s childhood dreams of paleontology.

———

GOMEZ: This is a good way to start, having someone bring a lighter.

WOOD: To smoke weed?

GOMEZ: Yeah. For you. I should make that clear.

WOOD: It was cool to walk around The Broad with you the other day. A rainy day Tuesday walk around The Broad.

GOMEZ: It’s shocking how many people were there.

WOOD: It’s a rainy day in LA, everyone goes to The Broad. It was cool to see some older work of mine that was in there, and your’s. When did you start doing graffiti?

GOMEZ: I feel like you get into a subculture around 13 or 14. I was pretty into graffiti around that age then all through high school. It was very parallel to art.

WOOD: It’s like a giant fucking canvas.

GOMEZ: I think it’s one of the reasons why I’m very comfortable making larger work. I really spent a good portion of my adolescence doing that.

WOOD: Was that your introduction to art, graffiti and people painting out on the streets? Were your parents into art?

GOMEZ: No, but my grandfather was an architectural draftsman and my uncles’s an architect. We both have to have a lot of planning involved in our paintings. Okay, I just got this lighter. Weed time. You grew up with art in your house, right?

WOOD: My parents both went to art school. I grew up with a Bacon and a Warhol in my grandfather’s house that he owned for a while before he sold them. Did you know you wanted to be an artist when you were really young?

GOMEZ: I wanted to be a paleontologist when I was five, but when I was six–

WOOD: What do paleontologists do?

GOMEZ: Dinosaurs. Like, an archeologist for dinosaur bones.

WOOD: You must’ve been a pretty smart kid.

GOMEZ: You said it, not me. When did you start making art? You didn’t go to undergrad for art, right? You went for philosophy?

WOOD: Psychology. I was thinking I was going to be a doctor until I actually gave into the idea of working on art all the time. Before grad school, I was working in a psych lab.

GOMEZ: Really?

WOOD: Yeah. I worked at a psychiatric facility where they did these functional MRIs of the brain. I studied abroad and that’s where I took my first art history class, and then I wanted to learn how to paint. It’s not a surprise to anybody that I’m an artist, except for me. I was always juggling the idea of not being all in because I was already doing something else.

GOMEZ: It’s interesting though that you use the phrase “all in,” because we were going to talk about poker.

WOOD: Yeah. 2004 is when the poker boom happened. ESPN was showing all this poker on TV and then everybody started playing it.

GOMEZ: It became a mass culture thing.

WOOD: Yeah. Lots of artists were playing. But as the stakes kept getting higher, less artists played, and more dealers and collectors did. Back then I was working for Matt Johnson. Then the real poker game started in 2006 at Blum & Poe with me, Matt, Mark Grotjahn, and a couple of Santa Monica art dealers. The coolest thing about poker is that it’s so social and you’re talking to other artists, but you’re not in the studio chopping it up about art that way.

GOMEZ: You’re not nerding out necessarily.

WOOD: It brought different generations together, and we started the World Series of Art Poker in 2021 where we’re like, “Let’s get more people from the art world to play poker with this group of people we already had going.”

Jonas Wood, photographed by Sayre Gomez.

GOMEZ: I still have never played a single hand of poker.

WOOD: Well, it’s not for everybody.

GOMEZ: Yeah. But I did love working with other artists, and for them. When I finished school in 2008, it was the recession. I was really fucked. I was scared about what I was going to do and couldn’t get a job anywhere. Then Kaari [Upson] put a show on. She needed someone to help her make this styrofoam grotto based on the Playboy Mansion. Then I became her first real studio assistant.

WOOD: You were still getting paid in beer at the time, right?

GOMEZ: I got paid in beer the whole time for that show. I remember at one point Kaari tried to fire me and I was like, “Kaari, don’t fire me. You should give me a raise.” I think I was getting maybe only $12 an hour or something crazy when I worked with her after grad school.

WOOD: We haven’t even talked about painting yet. I was wondering how you choose your imagery. How do you set up your studio to facilitate the paintings you want to make? You collect pictures and then do stuff on the computer, right?

GOMEZ: Yeah, I turn them from a normal image into something more unique or complex. Sometimes it’ll be a multitude of images, or only one, but usually there’s some editing that happens before it can be turned into a painting.

WOOD: You and I are quite similar, where if you find the thing that you want to paint then you can execute it. Knowing that your uncle and grandfather were architects, I guess you have to plan how you make this painting because you’re not an action painter.

GOMEZ: Certainly not.

WOOD: I’m not an action painter either.

GOMEZ: Recently we started using Maya to construct images. I’ll stage things and then have them photographed. Then you start the whole process of breaking the image down and turning it into a painting.

WOOD: So you use different tools and masking to paint. It’s very scientific and you take on these procedures that are refined to fit what you’re interested in, and then you start executing them as best you can under those parameters.

GOMEZ: Yes, with the guidelines that you set up for yourself.

WOOD: But still, it’s always a collage because you’re bringing aspects of each thing together. Like, this image is from here, this reference is from there, I cut this out and I moved it over here and then I changed the color of it over here. Mine’s the same way. I’m like, “How do I under-paint? What do I want to paint over the top?” I move things around, I’m sure you do too. I was curious how much you ever stop and then do something different on an image that you thought you were going to do.

GOMEZ: Like are there levels of spontaneity? I would say there’s not a lot of deviation in my process, but sometimes if there’s a drip, I won’t fix it.

WOOD: Right. I do fuck up sometimes, but usually I’m on a certain path.

GOMEZ: That’s it. But before it was a lot more open, now it’s a little more closed.

WOOD: What year is this painting from?

GOMEZ: This one is from 2014 or ’15.

Sayre Gomez, Untitled Painting with Trompe L’oeil Stumps and Trash Pile, 2015.

WOOD: Okay, so it’s 10 years old. The advancement in how you approach it and how you’re painting is evolving.

GOMEZ: I have a general set of guidelines, but I’m always trying to find a way to make that better. I was really disappointed because in my show at Hufkens we put a matte finish at the end of every painting, and it really desaturates the black. I was really frustrated with that, so I called Golden Artist Colors after my show and talked to them about the problem, and now they recommended some new products that we started using.

WOOD: The advancement in studio practice. We don’t talk about it as much maybe because we don’t have as much overlap in the paint department.

GOMEZ: Because you use oil and I use acrylic?

WOOD: No, because the application is so different. You were talking about advancements in the studio, like how you set up your practice. I’ve watched it grow.

GOMEZ: Every time you come, there’s new shit.

WOOD: Well, it’s how you’re able to figure out how to set yourself up for success in your own ideas and have people you work with help you achieve the kind of artistic and creative desires that you so wish to do. It’s cool to see. And that’s something that’s kind of related to poker, because once you start talking to people, not just about what you’re painting and what the value is of something, or what gallery you’re showing at or who’s buying your work, it’s more importantly about what people are doing in their studios and how they set themselves up to do well.

GOMEZ: Yeah.

WOOD: It’s cool to see, as your friend and observer, how your studio has evolved. We’re in this new studio now and it’s amazing to be in here, having this amount of room for your mind.

GOMEZ: It’s the best. I love a second space.

WOOD: Yeah. I wanted to be alone, and if you want to have people helping to make your work and you figure out a way where it’s not compromising, then you have to do that. But you still crave wanting to be by yourself.

GOMEZ: Yeah.

WOOD: It took me a while to be like, “I still need to be by myself a lot.” I had one assistant, and then I had two assistants, and then I had somebody helping me run the studio, and then I had kids. Talking to other dads is dope because it’s so crazy you’re at one point you’re totally free, married and staying up late and working in our studios at all hours, and then you have kids. Of course, my wife’s made way more compromises than me in life.

GOMEZ: Yeah, once you have a kid–

WOOD: The time continuum changes, right? We always talk about having to figure out how to keep the flow going. It became different to adjust to that deadline of time that never existed before.

GOMEZ: Yeah. I don’t have that many friends with kids. Your kids are way older, but it’s good because I have a better model to look to because it’s crazy right now.

WOOD: It’s an adjustment.

GOMEZ: It’s so hard to manage that balance. I’m still learning how to do that.

WOOD: You’re doing great. You want to be a really good dad, and you’re so into your work and trying to find the balance.

GOMEZ: Do you feel like your work changed a lot when you had kids?

WOOD: I’m literally making a painting of my kid’s art. Can’t deny that it’s connected. You think your work’s changed since you had kids?

GOMEZ: For sure. I just made a big painting of all their stuffed animals. You know what I mean?

WOOD: You’re saying that it wouldn’t be there if you hadn’t had kids?

GOMEZ: That wouldn’t be the subject of a painting. My work’s actually gotten darker since having kids because it just makes me think about more shit. They’re like, this catastrophic lens.

WOOD: Do you think it’s the lack of sleep?

GOMEZ: No, it’s the insane city that we live in. That hits so much harder now having kids, whereas before it used to seem like a novelty or something.

WOOD: Yeah. It’s influenced my life and my art so much. I don’t know if you could see it in my art as much as I feel it in my body. We’ve both been in L.A. for almost 20 years.

GOMEZ: It’s gotten way crazier.

WOOD: Are you talking about the scene or everything?

GOMEZ: From an artist’s perspective. It got way more expensive, obviously. There are also way more museums now than you used to have, like The Broad. And way more galleries.

WOOD: Way more galleries. The museums across the board have supported contemporary art in the most tremendous way, and the galleries and the collector group. Number one would be the artists because that’s why people were coming here before all those things.

GOMEZ: Before I moved here, I knew about my favorite artists, who were Ed Ruscha, Mike Kelley, John Baldessari, Barbara Kruger. Then when I moved here I learned about Jack Goldstein, who is still one of my all-time favorites. And all those people are in this show. It’s pretty crazy.

WOOD: It was really cool to see a Jack Goldstein painting at The Broad show and also see your painting. You had two different paintings in the show. You had a big landscape from 2022.

GOMEZ: Both of them are from the François [Ghebaly] show I had. One is this kind of burnt out carniceria in the Valley that I photographed one day. It almost looks surreal.

Sayre Gomez. The Whole Wide World is a Haunted House, 2022. Acrylic on canvas. 96 x 144 1/2 x 1 1/2 in. The Broad Art Foundation. Courtesy of the Artist and François Ghebaly Gallery.

WOOD: Yeah. This dystopian, abandoned landscape. The diptych is more hopeful and more titillating in the graphics and the doors. They’re two windows, right?

GOMEZ: Yeah, these decals that people put on windows. I think of them as, one is a whole story and one is like a portrait or a cameo.

WOOD: This is fucking hyperreal.

GOMEZ: It’s also cool because Patrick Martinez has those neons in the front gallery, so you see all the neons and then you see my painting right around the corner.

WOOD: A neon sign is fucking crazy.

Sayre Gomez. Diamonds and Pearls, 2022. Acrylic on canvas, diptych. 108 x 50 in. The Broad Art Foundation. Courtesy of the Artist and François Ghebaly Gallery.

GOMEZ: It’s pretty crazy that we pulled that off.

WOOD: I remember seeing it a couple of years earlier and François being freaked out by how bright it is, that you can achieve that kind of illusion. There’s the printmaking aspect of your practice, like how it’s separated and can be built, and then how it incorporates photography.

GOMEZ: It’s funny because there is no printmaking, but I borrowed a lot of the procedures.

WOOD: Yeah, because the things that you’re appropriating might have been printed that way.

GOMEZ: Exactly.

WOOD: So then you’re using the languages of a fucked up old vinyl.

GOMEZ: A crackling vinyl.

WOOD: Cool to see the [Jack] Goldstein. The one they had at The Broad was–

GOMEZ: They had two. There’s one that’s like a city being bombed, or something.

WOOD: The other one looked like a cell with little bits of rectangle missing that had a semi-realistic landscape in the background. It would be really cool to see more of your guys’ work together curated in the future.

GOMEZ: This is the preschool that your mom set up in the high school you went to, right?

WOOD: This is a daycare in Massachusetts that my dad built in the early ‘80s for all these parents that were having kids at a high school my mom taught at. Me and my sisters all went there, and it’s from these old pictures I put together. “Children’s Garden,” that was the name of the daycare. It was a way to go back to something that’s really important to me. It has all these amazing details that I like to paint.

Jonas Wood. Children’s Garden, 2015. Oil and acrylic on canvas. 93 x 93 inches. Courtesy of the artist and The Broad Art Foundation.