Cartoonist Michael DeForge On Butter Tarts and Anarchism

Photo by Matthew James Wilson.

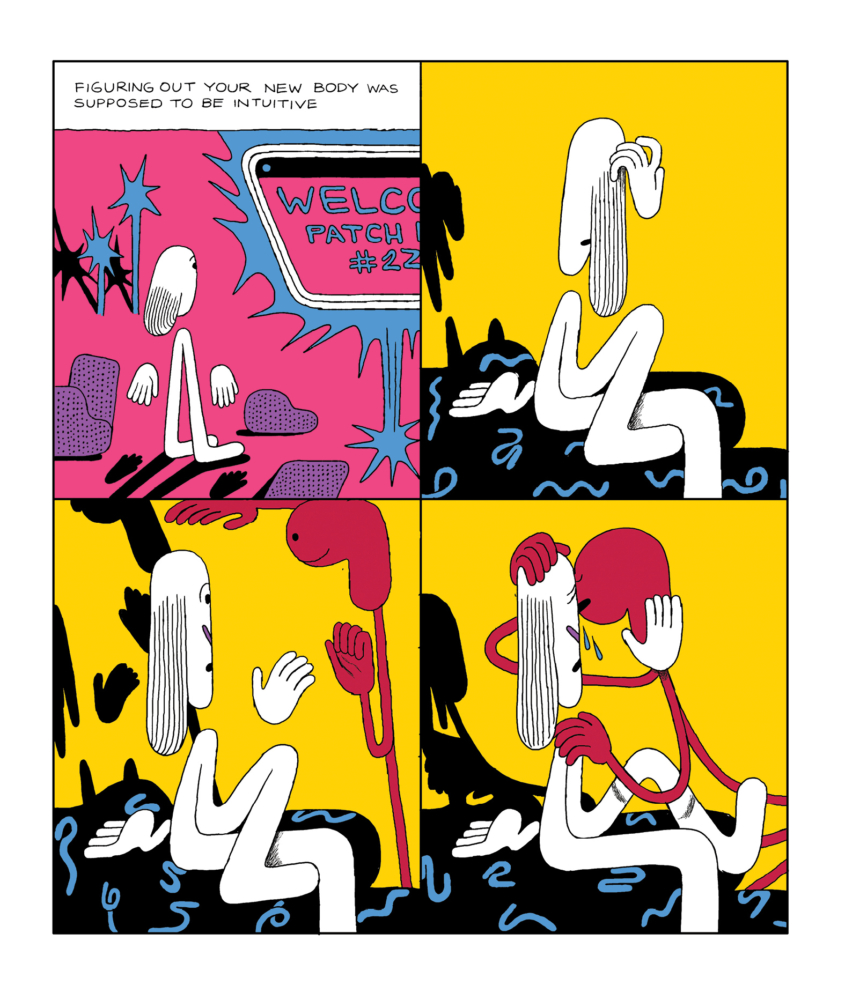

In the past five years, the Canadian artist Michael DeForge has published ten comic books, including Brat, Ant Colony, and Leaving Richard’s Valley, and worked as a character designer on Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time. In his work, DeForge has tackled performative art activism, communes, and awkward love. His new book, Familiar Face, is another DeForge classic—tender, depressing, and overflowing with his mind-melting, uber-satisfying surrealist style. Familiar Face grapples with what it’s like to live in a city and body that’s constantly being updated against one’s will. His unnamed protagonist’s job is to spend the day reading complaints she can never respond to for a company that keeps a line of job-seekers around the corner so she doesn’t slack off. The city is constantly morphing; holes appear in highways and apartment buildings get reshuffled overnight. Even her most intimate moments are filled with censored silence. Familiar Face is like a mirror that reaches out to slap you after you’ve seen your reflection. In a world defined by a cruel work economy and crippling isolation, will you remain passive? Are the crumbs of stability worth your soul? To quote Julia Reichart’s Oscars speech, Workers of the World, Unite!

———

ESCALANTE: Let’s cut to the chase—I know you’re a connoisseur of butter tarts. What makes a good butter tart and where can I get the best one?

DEFORGE: I think a good butter tart has to be kind of simple and delicate, because the flavors and filling itself are so decadent. I like a runny—not watery—tart. Hansen’s Danish Pastry Shop on Pape [in Ontario] makes my favorite!

ESCALANTE: How’d you get started on Familiar Faces?

DEFORGE: I wanted to do something about automation and algorithms and just a weird kind of collaboration between human inputs and what the algorithm puts out.

I was inspired by this new type of job that’s been popping up, like YouTube and Netflix taggers. There have been a number of articles about how weird and grueling and psychologically taxing this job is because they’re not really prepared to be doing something like going through YouTube videos and then being exposed to conspiracy theories, or really violent videos, pornography, things like that. But even sort of less sinister work, like Netflix taggers, where they just have to watch movies all day.

ESCALANTE: Do you think optimization is always negative?

DEFORGE: In an ideal world, having an ever-changing body would be actually very freeing. Something like the promise of Second Life or the promise of the internet—this thing where you can be anybody and you’re not tethered to a physical form. You’re not tethered to the way you conceive of yourself physically. This book is the terrible flip side of that—where you have no agency over how you change and you become completely free-floating and alienated from all of these things you used to be able to grasp onto before.

ESCALANTE: Have any recent protests informed the activism that you write about in the book?

DEFORGE: Certainly a lot of the current mobilizing around gig economy work. That was a big part of it, especially seeing the way the gig economy is just about to subsume basically all of our jobs and lives and work. Individual books and writers that informed this, too. Adam Greenfield did a book called Radical Technologies a while ago. A lot of it was about the ideologies embedded in technology themselves rather than technology being some sort of neutral thing that could be used for good or bad.

ESCALANTE: Did you ever work in the gig economy before doing art full time?

DEFORGE: Thankfully, when I was working in food service the gig economy wasn’t a thing yet. And that’s sort of what’s so shocking, how much worse everything has become. And that sort of informs the way I write about cities as well. Leaving Richard’s Valley was about cities and thinking about just how much less humane they are.

ESCALANTE: Is change possible? The good kind?

DEFORGE: Yeah, I hope. I feel like so much about being a socialist is having to be somewhat optimistic despite the world looking like shit.

It does feel like Canada has experienced a moment where there’s a lot of very real revolutionary potential. It’s exciting to see so many people mobilized against colonialism, against capitalism and directly targeting sites of capital by blocking rails, blocking intersections, harassing politicians in their offices, making them feel uneasy about going to work. I think the indigenous organizers and climate organizers mobilizing everybody right now and educating everybody really have a lot of revolutionary potential.

ESCALANTE: How has the internet, and especially social media, affected your career?

DEFORGE: I’ve been posting comics online since I was like 15. I used to be on Live Journal and a lot of my closest professional and personal relationships in comics have actually still come from Live Journal. So it felt natural to post it on Instagram. That’s the website people are on. When I’m serializing a work, I try to broadcast it basically to as many people and as efficiently as possible. Everyone’s on Instagram. I do kind of worry about how much more reliant we all are on these platforms for our livelihoods. It kind of replaced the cool, freeing, DIY aspect of putting work online that existed.

ESCALANTE: What was that like?

DEFORGE: That is now a very distant memory. Now it’s a pretty common occurrence that when one of these platforms goes under or changes their policy or goes out of vogue, it suddenly affects the lives and livelihoods of a ton of artists that they’ve been profiting off of while we kind of end up having to beg for scraps from them. Most artists working online will feel that way about Instagram, Twitter, Patreon, Big Cartel, Etsy, whatever it might be.

ESCALANTE: How do you weigh making your work accessible online versus your need to support yourself?

DEFORGE: I’m luckily in a position where I make most of my income still from commercial illustration, so I’m not super reliant on my books alone to float me. I sort of assume that if someone reads my work for free online and then doesn’t buy it in a book, they probably weren’t going to buy it anyway because it means they didn’t have money or didn’t like it that much. And so I’d rather they read it than not read it and luckily I do have enough of an audience that is supportive and generous enough to buy it in book form when it does come out. I am grateful that I got to incubate on an earlier version of the internet, just because it does seem sort of…

ESCALANTE: Competitive?

DEFORGE: Yeah, the stakes being lower was really nice. It was great to be posting work to a group of like 20 or 30 like-minded artists in a more closed space. I thought that was a really nice way to cut my teeth and develop and interact with like-minded artists and learn from them and grow. Whereas now it does sort of seem like you’re just thrown into it and forced to compete amongst millions of other voices rather than incubate in a smaller little setting.

ESCALANTE: How do you think your background in animation has affected the work that you produce today?

DEFORGE: Working in animation really taught me to be a more efficient cartoonist. When I started my job [at Adventure Time], I didn’t have any formal training in animation, I didn’t have any formal training in art period. And I hadn’t had the experience of having an artist or professor go over my work and criticize it and correct it. Working in animation, I was working under cartoonists who I respected so much and were so skilled and so efficient. They taught me a lot about drawing more economically because in animation, if you can do something in three lines rather than ten, you choose the version of it that you did in three lines. It really made me learn how to simplify my artwork and pair things down, and I think I’m a much more elegant cartoonist because of it.

ESCALANTE: When did you know you were going to commit to your art?

DEFORGE: Weirdly, I didn’t think I’d be able to make a career out of it until I actually got hired by Adventure Time. Before then, I just assumed it would be the thing that working in kitchens would subsidize. But yeah, I was lucky enough to get picked up by Adventure Time when I was pretty young and didn’t have a plan. I just sort of stumbled into it. I feel like so many people just gave me opportunities really early.

ESCALANTE: I heard you’re a big runner.

DEFORGE: Yeah, I run a lot of half marathons. I like racing.

ESCALANTE: I heard Haruki Murakami runs a 5K before he writes. Do you do the same?

DEFORGE: Not really. Though I sometimes think of running as the closest thing I could ever get to meditation. I generally have a lot of buzzing kind of pent-up energy and I think of running as a way of really beating my body into calming down. I beat up on myself a lot and I feel like running has become the least unhealthy way to do that for me.

ESCALANTE: Have you ever found it difficult to get to the table and to start working?

DEFORGE: I’ll just start and end up drawing like 30 pages of garbage before I start getting to the real work. And I just think of it as clearing out the junk in my head or something.

ESCALANTE: Do you believe that art can be an effective form of resistance?

DEFORGE: Someone like Ursula K Le Guin is an example. For me and others who came to her work their introduction to anarchism and socialism was through the way she’d explore it through fiction. A lot of art allows you to see the potential for something better. I have this idea that all art is political, but not all art is politically useful. I don’t know if mine is.

Art at its best can both articulate something that you might recognize in the world, something that bothers you or some aspect of the world that something that you knew was wrong, but haven’t put the words to. And I think it can also explore new ideas—alternative ways of being alive.