Julian Schnabel

I wouldn’t lowbrow someone or insult them by repeating myself in a way where they could just go, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s a Schnabel painting. I got one.’ Julian Schnabel

Julian Schnabel may be one of America’s most famous living painters. But in a strange but appropriate twist for a man whose body of work now spans five decades, his paintings are less instantly identifiable—they elude the instant iconic familiarity that turned many of his contemporaries rising in the ’70s and ’80s into visual brand names. This paradox may be explained by Schnabel’s overwhelming success as a film director, helming such cinematic masterpieces as Before Night Falls (2000) and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007), ever since he broke into movie-making with Basquiat, his 1996 biopic of his late friend, the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. (In fact, Schnabel, along with his studio assistant Greg Bogin painted the works used in Basquiat to showcase the young artist’s feral spirit).

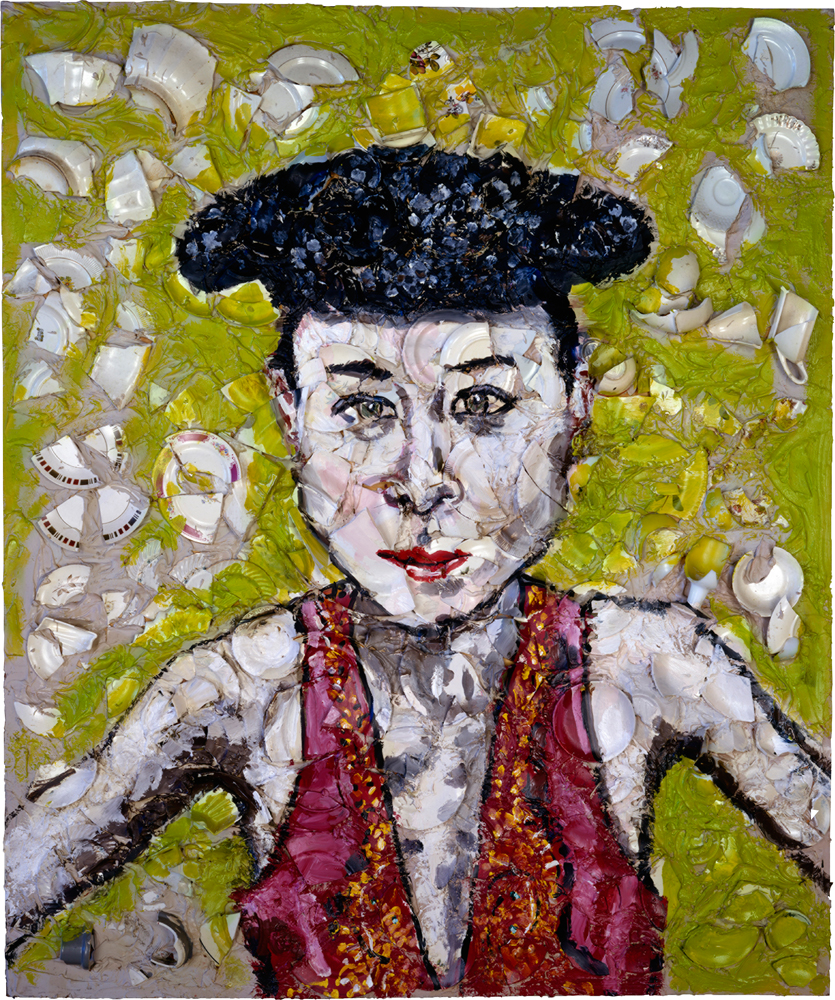

Triumph in cinema is seemingly always destined to eclipse development in the more rarefied circles of visual art. But the public’s inexperience with the breadth of Schnabel’s art productions is also due to the 62-year-old, Brooklyn-born artist’s ingrained painting strategy: He simply refuses to keep making one kind of work, or operate in one style, by splitting open the same vein until it runs dry. Ever since he created his early Wax Paintings series, starting in 1975, Schnabel’s range of materials and modes of construction have been so varied that it seems as if no fixed surface is safe from his application: There are velvet paintings, oil paintings, paintings on wallpaper, on mirror, on tarp, incorporations of photography, incorporations of found objects (literally found on the road or in water), a graffiti-esque stroke, a spill, a stain, and in his Hurricane Bob series he used his car to drag a tarp behind him on the road so the asphalt would leave a burning mark on the fabric, and then left the tarp exposed to Hurricane Bob in 1991. Perhaps most famous are his Plate Paintings series of smashed crockery that he procured from thrift stores and concretized on canvas as abstract destruction sites or in the form of vulnerable portraits.

Schnabel is an artist as equally obsessed with time—how all of these disparate elements come into union provisionally but eternally on one plane—as he is with exploring the possibilities of a how a mark can be left as a trace. With expected bravado, Schnabel follows the en plein air technique of painting; a lot of his work is made in his outdoor studio in Montauk, a roofless room that allows him to see color and shape in their natural light. In a sense, it could be argued that all of his works are landscapes of one variety or another.

This month, Schnabel brings his dedication to his first passion to the Brant Foundation in a carefully selected retrospective. It is a long-overdue opportunity for the public to survey a master mark-maker whose influence on a young generation of male painters has been colossal. One talent who has been inspired by Schnabel is L.A.-based painter Mark Grotjahn. The two took time out of their workshops (and Schnabel’s hectic travel schedule with his partner, May Andersen, and their new baby) to discuss Schnabel’s priestly commitment to his practice. And like a priest with the divine, Schnabel sees paintings everywhere. That might be the soundest definition of a calling. —Christopher Bollen

MARK GROTJAHN: Hi, Julian. Where are you?

JULIAN SCHNABEL: I’m in Copenhagen, in Hotel d’Angleterre, with May, the baby, and the nurse. I’m having a show in Frederikssund with Francis Picabia and a guy named [J.F.] Willumsen—who would have had his 150th birthday on Saturday, except he’s dead.

GROTJAHN: How old would Picabia be?

SCHNABEL: Picabia was born in 1879 and died in 1953. And the other guy was born in 1863.

GROTJAHN: When were you born?

SCHNABEL: I was born in 1951. The whole weird concept of this show is that this guy Willumsen is being redefined by work that came after him. He knew Gauguin in Brittany, he painted a lot in Venice, and he donated his collections to this museum. It’s a really odd and interesting show about hybrid painting—it’s about the imperfect.

GROTJAHN: I’d like to see it.

SCHNABEL: I guess I’m the only artist who’s alive in the show.

GROTJAHN: You had your first show in New York with Mary Boone in ’79. And then you had another one right after it that same year, correct?

SCHNABEL: Exactly. One was in February and one was in October.

GROTJAHN: Did you prefer one show over the other?

SCHNABEL: Well, I wanted to show the plate paintings that I had made in 1978. When I made them, I was excited. I think when Mary saw those paintings, she felt they were kind of terrifying or scary to deal with. I mean, she thought they were good but they seemed kind of radical, and she thought it would be better to show the wax paintings I was working on first and save the plate-painting show for later. Actually, I thought the show was going to happen much later, but a guy named Paul Mogensen dropped out for some reason that month, and all of a sudden I had the show in February.

GROTJAHN: You know, I got my first show at Blum & Poe because Paul McCarthy postponed his show, and they came to my studio and asked me if I could put together a show in two weeks. I just said, “Yeah, let’s do it.”

SCHNABEL: There’s always somebody applying for the job.

GROTJAHN: Yeah, I hear you. So how did those two shows work out?

SCHNABEL: I showed four wax paintings in the first show and I was happy with that. But, you know, when you’re young, you’re anxious to show things—you want to show the last thing you did. In the second show, I showed four plate paintings and one wax painting. It’s funny because Mary had this small gallery in the same building as Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend. It was a clever thing that she did, even if her gallery was the size of a closet compared to theirs, because she’d be in the same building, 420 West Broadway, where everybody would walk up the stairs and invariably see what was in her gallery. They were already there to see what was in Leo’s gallery or Ileana’s. [Gallerist] Annina Nosei was the person who ended up buying my first plate painting.

GROTJAHN: Which one?

SCHNABEL: The Patients and the Doctors [1978]. I think she bought it for, like, $3,500. I think I got $1,700 of it. Something in there—I’m off $200 one way or the other.

GROTJAHN: That might have paid for something back then.

SCHNABEL: Yeah. What happened was that when it came up at auction, she promised that I could buy it back. So I gave Sotheby’s the fifth plate painting for her and Annina sold that one and got $93,000 or something. So I have that first one back now. But we are talking less about painting right now than the machinations of the beginning of my relationships with art dealers. [laughs]

GROTJAHN: But those early interactions are interesting. You got to see how the public responded—more than just showing your friends your work. The reaction is really out of your hands.

I never saw art as being a career. It’s just some people want to make things, some people don’t, And the people who do, get defined in the world by the things they make. Julian Schnabel

SCHNABEL: I think that’s an interesting way to put it. I sort of saw it from a different angle. I feel like these days the exhibitions that get credibility or attention have more to do with some kind of infusion of money from their market peers. Back when I had those shows, there wasn’t the same setup to assimilate young artists into contemporary art. There wasn’t that much money around it either. I mean, you could make three or six thousand dollars, but that didn’t matter so much. Even if your show sold out, what you did was put your paintings out in a market of free consciousness in some way and people walked in and were hit by an experience. I’d say it was a relatively greenhorn or naive sort of art experience in contrast to the strategizing and Machiavellian shit that goes on now. It’s funny, I wouldn’t have said it then, but I think it was a much more naive and less convoluted time. Do you believe that?

GROTJAHN: I’ve looked at that show. It was basically one painting per wall. I got the feeling you wanted to give the paintings some breathing room—that you wanted to allow the paintings to speak. I felt like you treated the space and your work with respect. You did that as a 27-year-old, and I think that still kind of flies today.

SCHNABEL: Yeah, I did it then; I do it now. I take a painting out if it’s too much or just try to give somebody the clearest experience they could have. On the other hand, I wouldn’t lowbrow someone or insult them by repeating myself in a way where they could just go, “Oh, yeah, that’s a Schnabel painting. I got one.” I never saw art as being a career. It’s just some people want to make things, and some people don’t, and the people who do, get defined in the world by the things they make. But I’ve been painting since I was little, and I shift gears—I even shifted gears into making films. But I never stopped making paintings.

GROTJAHN: You work with a lot of different styles and use a lot of different systems and techniques in terms of shifting from one thing to another. How do you make the decision on what to do? How does that happen? Because you do make bodies of work.

SCHNABEL: I see paintings everywhere. I look at stuff and it looks like painting to me. Making a painting is like playing the saxophone. You hit the note and it comes out. I think my paintings are about time—a lot to do with time and different levels of things that are having a parallel life. Like this goat painting I made recently [The Sky of Illimitableness, 2012]. I’m only calling it a “goat” painting because there’s a goat in it. I put everything in that painting—the wallpaper, the goat, a purple stain. The only way all of those entities are going to meet is in a painting. It’s all right there, forever, eternally, bringing you into the present. Hey, I just found the catalog from the Willumsen/Picabia show. I’ll read you a quote from me that they used in it: “Signaturizing is getting paid to stop thinking. (America loves signatures to the point of dullness.) Signaturizing is a trap. It is artists believing that their work should always have the same appearance. They’re satisfied to let this appearance be the emblem of their art, because it’s what people have come to expect them to do. This is either a sign of arrogance, resignation, or atrophy. (Maybe they only have one idea and I’m being too hard on them.)”

GROTJAHN: Is that from your autobiography [CVJ: Nicknames of Maitre D’s & Other Excerpts From Life, 1987]?

SCHNABEL: It’s not an autobiography. For me, that book is on-the-job training notes. Like, if you are a young artist going crazy, you could turn to page 54 and see, “Well, that happens,” and you know you’ll get over it, you’ll go to sleep, you’ll wake up tomorrow, and it’ll be okay.

GROTJAHN: That’s exactly how it worked for me. For me, that book was a really generous insight into what it was to be a professional artist, a functioning artist, in society or in New York City. It opened up, in a way, some of the possibilities as well as ways of looking at paintings.

SCHNABEL: I hate it when people call it an autobiography, because they say, “Oh, he’s 35 years old. Why is he writing an autobiography?” I’m 62 years old now and I wouldn’t have written it now. It was coming from the voice of a 35-year-old. What I did with that book is that I didn’t have a diary but I made believe I did. I used the dates to jump around in time as a structural element like I was writing a script. So it was anything but an autobiography. It was exactly what it is: I’m fucking going crazy, I’m drinking, I’m smoking 15 cigarettes in half an hour, I have paint all over my face and arms, and I’m trying to make a black painting, but it’s got to be in a million different bright colors, what’s wrong with me? You try to put that down and somebody else feels just like that at four o’clock in the morning somewhere. We’re lucky we can paint. It’s amazing to have that outlet to actually know what to do with your hands or know how to start at least. It’s like listening to Elliott Smith songs and being able to hear all of that loneliness and alienation … I am trying to make sense of what I’m saying to you. I feel like you know more about what you want to say than I do, which is good.

GROTJAHN: What do you think I want to say?

SCHNABEL: About painting, about whatever effect my work had on you. And I’m trying to think of how it felt to me to be me. Thinking about this show that I’m in with Picabia and Willumsen … You know, Picabia became estranged from his surrealist friends at the end of his life. They thought his work was embarrassing. Marcel Duchamp sent him a note days before he died, “A bientôt, cher Francis.” And Willumsen was just so damn frustrated because he lived to ninetysomething and he was feeling hopeless. What’s interesting about making art is that you take everything you know about it and you bring it up to that point, and you start making a physical thing that addresses what that is. And when you do it, you don’t know anything about it—if it’s going to work or not work. That’s what’s so great, I guess, and so disturbing about it at the same time: you don’t know. And it’s about not knowing. It’s about feeling your way through something and then seeing if it comes out. And if it does, then you feel really excited and you can be in love with the thing or in love with the feeling you get from the thing, and you feel like you saw something that didn’t exist before. But while you’re doing it, you don’t know what the hell you’re doing. So if I made a painting and someone said, “How long did it take you to make it?” I’d say, “62 years and five minutes,” even if I might have done it in a second. You kind of come up to the mound ready to pitch that thing, and you don’t know if you’re going to get that ball over the plate, and that’s why you’re thrown the ball.

GROTJAHN: Well, just for the record, I’m not trying to get you to say anything. There’s no agenda here.

SCHNABEL: Oh, I know. I just meant you seem so clear about your thoughts and I don’t. What keeps coming into my head is, I’ve been driving in a rented car and it’s got GPS. I’m looking at how the GPS diagram moves on the screen. And it’s making these beautiful curves as I drive.

I think my paintings are about time—a lot to do with time and different levels of things that are having a parallel life. Julian Schnabel

GROTJAHN: Are you in the car now?

SCHNABEL: No, I’m still sitting in the hotel room, but funny that you ask me that question. I remember Rosamond Bernier telling the story in her memoir about how Peggy Guggenheim accused Max Ernst of having sex with Rosamond when they went out on a bicycle ride, and he said to her, “Not even I can make love on a bicycle.” I definitely can’t take a photograph of the GPS in my car, talk to you on the phone, and sit at the table in this hotel. But anyway, I was looking at the way this diagram moved around and I saw so many paintings. I’ve got to paint some GPS paintings.

GROTJAHN: So that happens often? You have visions of paintings and then you paint them?

SCHNABEL: Yeah. It happens all the time. Sometimes I’ll dream that I saw a show and then I’ll wake up in the morning and realize that I didn’t see the show, that it was my dream. And I just remember what the paintings look like in the dream and I think, “Oh, nobody painted those. I can do that.”

GROTJAHN: That sounds nice.

SCHNABEL: Then sometimes my kids might tell me they had a dream or and maybe I’ll paint some paintings from their dream. That’s one good thing you get from your kids. Rob them of their dreams. [both laugh]

GROTJAHN: I’ve got two girls, and they both make beautiful drawings. One of them really has a gift for the way that she colors around certain lines. It is phenomenal. I’m trying to get some of that going. I don’t know if I’ve seen The Teddy Bears Picnic [1987] at your house but I’ve seen it in photographs. Is that going to be in the show?

SCHNABEL: You did see it at my house, but I don’t think it’s going to be in the show. I don’t think it’s going to fit on the wall that we are thinking of putting it on. But I am going to show Ritu Quadrupedis [1987] and Pope Pius IX [1987]—two paintings from the Recognitions group.

GROTJAHN: What’s your relationship to the found object?

SCHNABEL: The thing is, it’s great when I find it. I was paddling out near my house in Montauk and there were hardly any waves in the summertime at all. I was just paddling down to the old Warhol place, where I used to live, and as I was paddling back I saw these pieces of turquoise or cerulean blue foam that were on the bottom of a dock and kind of strewn across the beach. I paddled into the beach, tied the pieces together with some fishing rope to my surf leash and paddled them back to my house. I took them to the studio and put some feathers on them from the 18th century and they looked pretty cool. I can show you some images of them.

GROTJAHN: Yeah, I’d like to see.

SCHNABEL: So what’s my relationship to the found object? I mean, I paddled out there and I was just going to have a day that would sort of run into all of those days that disappear. But by finding those blue pieces of foam, it made that day an event. And those things are really important to me. They were something to think about. They were fun and it was something that was instant and it was a gift. The same way the GPS diagram is a gift, or just seeing paintings everywhere all the time.

GROTJAHN: Like the Chinese woman in the hammock in the Untitled (Chinese Paintings) series.

SCHNABEL: It was painted on a mirror that I had given to Jacqueline [Schnabel’s first wife], and there were magnesium spots that were breaking up on the glass. I liked the way they looked like ringworm or some kind of pockmarks and I also liked the way that the paint was enameled to the glass. When I photographed it and put it through a printer, the color changed in the rain and the weather, so I photographed that and then photographed the mildew that was on it and the painting that had been embedded there with all the impurities and ended up with a thing that was some coded cornucopia of possibilities and meanings and a time map. Time is something that’s important to me—the whole feeling of time.

GROTJAHN: You mark the time.

SCHNABEL: I wanted to tell you that I went to Colorado and saw your show at the Aspen Art Museum. I was with people who really didn’t know anything about art, and I had to explain it to them. I was able to find a lot of words to say about it. What was interesting was to look at your paintings and think about my paintings, because I felt like my paintings really spoke to you and you answered me in your paintings, and that was one of the only times that’s happened. I mean, it’s one thing when somebody copies your work or just steals some shit from you or whatever, but it’s another thing when someone’s painting their way and you are painting your way and you know what you were doing spoke to them and let them be themselves, and then they kind of answered you in their painted way. There’s a painted dialogue going on, and there is no lying in that. So, when I looked at those things, it kind of hit me in a way that was personal. Like, I felt like you knew me in some way that 99.9 percent of the people in this world will never know me.

GROTJAHN: Painting is a really fucking weird and specific language. I think anybody can get something out of it, but to be fully engaged in it and dedicate your life to it is a different thing.

SCHNABEL: It’s interesting to understand how I would approach something and see how you approached it and see why I would understand even if I couldn’t figure out how you are making some particular mark. It could be as simple and obvious as something that’s right in front of me, but there’s something about when it all comes together—there’s this magic that happens. Magic might be something we need to talk about. Certain things just don’t have it and certain things really do.

GROTJAHN: Do you care if people like your work?

SCHNABEL: I could say, “I don’t care. That’s for other people to worry about.” I did say to somebody the other day, basically: “I don’t give a shit. I could drop dead. And I’ll have my show at the Louvre when I’m not around, and the paintings will speak for themselves.” That being said, if you want me to be honest, do I care what people think of the paintings? Yeah, I do. How they value them and where the sit in the context of other painters who I thought were important … For example, the fact that Andy Warhol just had a show over at Peter’s place, and I’ll do it after him, I think that makes sense to me.

GROTJAHN: Coming up in New York, who did you hang out with? And who do you miss?

Paintings are not like the Internet. they’re not like movies. they’re not electronic-friendly. You have to go see them. you have to stand in front of them. Julian Schnabel

SCHNABEL: I knew Clyfford Still when I was a kid. I knew Robert Smithson and a lot of these guys who were hanging around at Max’s Kansas City. I was the youngest artist there. It was 1974 and the place was closing, and I think these people felt like I’d been around since late ’60s or whatever, or they knew me in some way. I remember bringing Jeff Koons to Max’s one night, and we were sitting with some older painters and one of them said to him, “What do you do?” Jeff said, “I present the new.” He was making the vacuum cleaners that were in these plastic boxes in this apartment on Seventh Avenue across from Barneys. I actually knew Bill de Kooning too. I came back to New York in 1973. I lived in Joel Shapiro’s studio on 54 Leonard Street in the summer in exchange for painting his walls.

GROTJAHN: Peter Brant in November: what is that show going to be like?

SCHNABEL: I guess it tells my story. It shows what I think is important—meaning what moments were important. I can just put what will fit in that space. It’s a big space and it’s ample enough for anybody that goes to see the show to see what my work is about and decide if they like it or not. Obviously, my criteria is for things that speak to each other, that present the different inventions or qualities that would be specific to my work. They’re threads that go through the work. And also to present the expanse of the work, because obviously I was not the kind of person who felt like they had found an irreproducible image that they just wanted to repeat every time in different colors or different sizes. In a sense, I’m like an actor acting out different parts. So I’ll be an Indian sign-painter for a while. Then I’ll be a 17th century Spanish painter for a while. There’s this story I always loved about how Chinese calligraphers used to change their names mid-career so they could start over as somebody else. I never felt like I needed to just repeat myself or copy what I did. I never wanted to just accept that. So there’s a sense in my paintings of one layer and then there’s something that happens to it. Sometimes when I put these white marks on, it’s as if somebody else came and did that to the canvas. I like the notion that there’s this quality of temporality—that somebody died and another person came by and did that, so the painting is unendingly open to the present. There are generations of people who have never seen a big plate painting in person. And they don’t know what the hell they look like, they don’t know what it feels like to stand in a room with them. Paintings are not like the Internet. They’re not like movies. They’re not electronic-friendly. You have to go see them. You have to stand in front of them. That’s the great thing about them.

MARK GROTJAHN IS A LOS ANGELES-BASED ARTIST. HE WILL HAVE ONE SOLO EXHIBITION AT THE NASHER SCULPTURE CENTER IN DALLAS, AND ANOTHER AT KUNSTVEREIN FREIBURG IN FREIBURG, GERMANY. BOTH OPEN MAY 2014.