Unbranding Brands

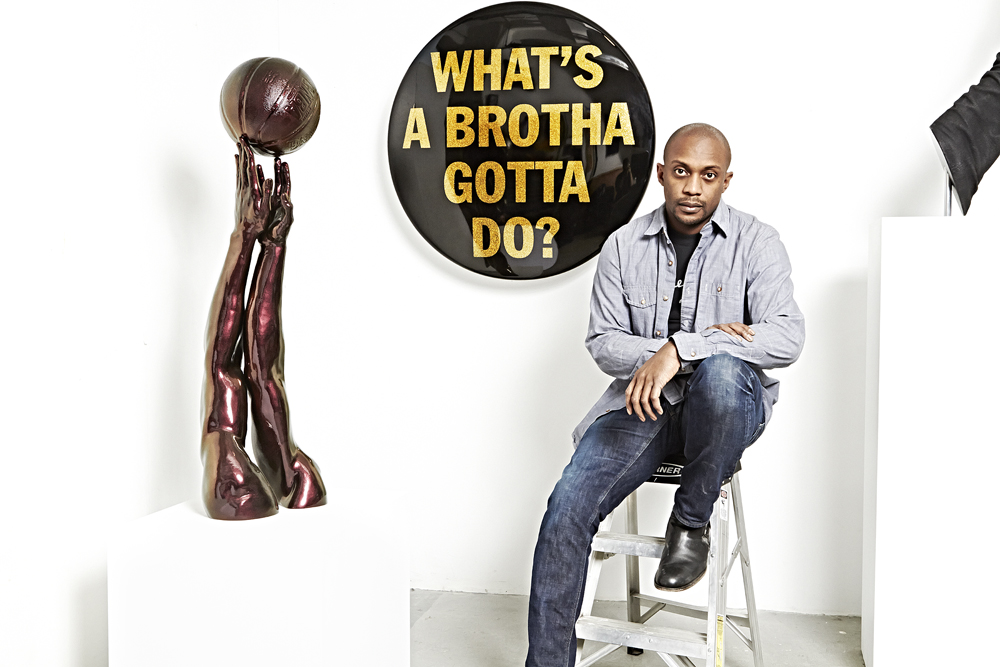

HANK WILLIS THOMAS IN NEW YORK, MARCH 2015. PORTRAITS BY HAO ZENG.

Flipping through more than 100 advertisements that are stripped of all words and context and guessing what they mean is an exercise for the brain. Nevertheless, last week, for more than an hour, we sat in artist Hank Willis Thomas’ midtown Manhattan studio doing just that. The images we viewed compose his most recent body of work, “Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015,” which will go on view today at Jack Shainman Gallery in Chelsea, and delves even further into the artist’s previous explorations of power, beauty, privlege, and desire in America.

When viewed as a whole, the 101 images collected from the last century (one from each year), as Thomas says himself, become akin to looking at a brief synopsis of cultural history. The mixed media artist removes language and recognizable symbols, leaving only the original photographs for consideration. Throughout the series, the portrayal of women reflects cultural developments, and oftentimes the lack thereof—some are empowering (on Mount Rushmore), others horribly violent (a man literally dragging a woman by her hair), and others sexualizing the woman’s body (women flaunting bikinis standing in a truck bed; a woman scantily clad sitting in a martini glass). By isolating the images from context, Thomas begs the viewer to consider the subliminal messaging of advertisements, as well as how they reflect, or hinder, society’s progress—a concept he has used before.

Prior to “A Century of White Women,” Thomas presented “Unbranded: Reflections in Back by Corporate America, 1968-2008,” in which he employed the same overall process, but used two advertisements from each decade that were all geared toward an African American audience. Although Thomas forges his own artistic path, it begins where his mother, Dr. Deborah Willis, the Chair of the Department of Photography at NYU, left off. Following his year and a half of research and completion of this project, and prior to the opening of “A Century of White Women,” we met the New York-born, bred, and based artist at his studio to discuss all things past and present.

HANK WILLIS THOMAS: It’s interesting how ads become a narrative of the cultural time. That’s one of the things that I think is interesting—the project kind follows all these amazing moments in American history. You can see the progress! [laughs] You can also see some things we haven’t quite let go of.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: Like sexualizing women.

THOMAS: Which wasn’t there really, early on. It almost emerges after WWII.

MCDERMOTT: You see that women want a freedom in the postwar era, but we’re still tied to our gender identity.

THOMAS: It’s like your agency is partially through what you can show.

MCDERMOTT: What made you want to work with women and whiteness, opposed to African Americans as in your previous projects?

THOMAS: All of my work is about framing and context. Compare this image with another from 15 years before—look at her body. [points to moles on the woman’s body in the older image] These were called beauty marks at some point, but they’re gone now. And whose face looks like that? It’s even, toned, polished. We’re all conditioned to learn our standards of beauty through these images. You realize that even the people who are “supposed” to epitomize it, they don’t even look like that. The sexiest models—she’s blonde-ish, but still has to have a fake face! [laughs] And god knows what else. How can you best investigate or critique these beauty standards, or our entire value system, without really looking at the images we are conditioning—not just each other but children, future generations—to value? And also, we see dramatic shifts from pretty much every decade, as far as what’s appropriate, what’s valued, what’s respected.

The reason I’ve talked about blackness in a lot of my other work is because, to a certain level, it’s easy to designate or to define. I think of race as the most successful advertising campaign of all time. Someone brought up the irony of statements like light skinned and black. Like, what does that mean? I’m black, right? But I’m brown, clearly.

MCDERMOTT: But then brown is Indian.

THOMAS: Or Latino. And [my studio manager’s] yellow. There’s all of these divide-and-conquer strategies that race is based off of, but the differences are arbitrary. You can make differences about height; you can make it about eye or hair color; you can make it about tone of voice. I think about whiteness as being this relatively new construct, but also, what it meant to be white in 1920 or 1915 is very different than what it means to be white today.

MCDERMOTT: Meaning Lithuanian, Italian, Irish people, they weren’t considered white.

THOMAS: Right. Lithuanians really snuck in there. Armenians are making their way. I think of whitness as the blob; it’s this thing that you can slip into. That’s what I’m trying to call attention to with the project: the problematics of race and gender positioning, the problematics of demographic marketing, and what are the standards to which we understand what we’re looking at, what we desire, and what we buy into.

MCDERMOTT: I read a story from when you were younger and saw the image of Jordans at the shoe store and then really wanted them. When did you first start really thinking about advertisements and their meanings?

THOMAS: I guess you could argue it was then. We are the cable and MTV generation. I think I became aware of the power of ads through my youth. It’s entertaining to look at ads, to try to decode… There’s a movie called They Live. It made a huge impact on me. I’m sure you have no idea what it is.

MCDERMOTT: No, I don’t.

THOMAS: Well, you’ve seen the residue of it all over. It was a movie starring Rowdy Roddy Piper, who was a WWF wrestler. He was the bad guy at first and became a good guy. In his good guy phase, he became an actor, and in his actor phase he did an action movie. The movie is in L.A. and basically the world had been taken over by aliens [and] they’re putting messages everywhere. He finds this package of sunglasses and when you put the sunglasses on, you can see who the aliens are, but also the real message behind all the ads. So all of a sudden you realize there’s something that lies beneath all these things.

I was, like, 12 when it came out, but you realize how ads really aren’t about products. Every advertisement has a subliminal message, even if it’s not direct and overt. What I like about unbranding is it forces us to really start to ask the questions—take off the disguise and look at the image.

MCDERMOTT: Are you looking for answers or just questions?

THOMAS: I think art is always about the questions. The design is about the answers. When you unbrand it, you turn it into a question; that’s when it becomes art. I think advertising is the most ubiquitous language in the world. How can you ignore it? I think it’s underused for it’s actual power and potency to deliver a message. Mining it is so important for artists working in the 21st century.

MCDERMOTT: Your mother also clearly works with a lot of the same themes. Do you think you would be as committed to this if it wasn’t for her?

THOMAS: No. My mother’s work made me realize the power of photography to tell a narrative. Whoever is holding the camera or the paintbrush is creating the history, telling the story. The erasure of Africa—it’s such an incredible campaign, the way they’ve tried to erase Africa’s history. You wonder how much was erased when you see the few things they couldn’t destroy, like ancient Egypt. Where’s Egypt?

MCDERMOTT: In North Africa.

THOMAS: But you’re in the Met, and it’s African art this way, Egyptian art that way. People in Egypt were like us, but everyone had a different complexion because it’s a cornerstone where people are having sex. But we see movies like Exodus [: Gods and Kings] with Christian Bale. There’s one thing we can be absolutely sure of as far as historical accuracy: there were no Anglo-Saxons or Nordic people in Mesopotamia or Africa. That’s a hundred percent positive, but they’re like, “Not in our stories!” That erasure; that’s what race is about.

When the tombs were found in the 1920s, the King Tut was a hairstyle, part of the low-cut bob. That is another thing about globalization and exoticism: it’s appropriation, to the degree that if you try to do a movie about ancient Egypt with dark skinned people, other people are going, “I don’t get it. That didn’t happen.” So you wonder, what happened to the other cultures that did not build huge structures that you can’t just obliterate?

MCDERMOTT: It points to the fact that by and large we refer to Africa as Africa, not 52 individual countries—how many of those can someone actually name?

THOMAS: Right. Tunis is even different from southern Tunisia. But that’s the thing. If people hadn’t been having sex for generations, for centuries, there’s all of this kind of stuff that I’m trying to start to talk about through my work. What makes one person white? What’s the definition of a continent? [pauses] Tell me.

MCDERMOTT: I’ve seen something where you say that Europe is really a part of Asia, because continents are divided by imaginary lines that we put in place.

THOMAS: Exactly. You can make an argument that North and South America are different continents, but Europe is definitely a part of Asia. The fact that Europeans were able to create the story, they’re like “Those people are in the East. They’re in the Orient.” It’s like, ‘There’s more people over there and they’ve had a longer continuous history, but they are the ‘others’ over there in the East.” Then on all the maps, Europe’s in the center. That’s the power of being able to tell your story.

MCDERMOTT: One of the first classes I took at NYU was your mother’s, The Making of Iconic Images—

THOMAS: That’s the thing—frequently, I’ll be doing stuff and I’ll find out later it would’ve been much easier if I had just talked to my mom, taken her class, read all her books. And Shelley [Rice, who wrote the introduction for the exhibit and also teaches at NYU], she talks a lot about how images are placed in advertisements, that juxtaposition.

MCDERMOTT: I took her classes too, and I wanted to ask you about something similar. In one class, we looked at two advertisements for the same brand of alcohol, but one was geared toward an African American audience and one toward a white audience. The white image had one or two drinks, the woman was wearing a ring, and they were conservatively dressed. Whereas, the African American one had four drinks or so, there were no rings, and the woman was dressed more suggestively. Would ever consider working with comparisons?

THOMAS: Yes. There are so many things like that I am interested in. Another thing is [an advertisement’s] art historical roots. Every advertisement has an anatomy, whether it’s the gesture of someone’s hand, or the background, or the lighting, and you could probably find it all in art history. I’m interested in that, in looking at all the ancestors to a specific image.

MCDERMOTT: Growing up, who was one of the first artists that you became acquainted with that motivated you pursue art?

THOMAS: I wouldn’t say I ever pursued art, ironically. Art pursued me. You know, I didn’t go to openings because I wanted to; I went to openings because my mom dragged me. The artists there were my mom’s friends and I didn’t want to be like them because they were all broke. [laughs] The lives of 99 percent of artists are not luxurious, so it did not look great to my 12-year-old brain. Even apartments in SoHo, I noticed it was kind of big, but I was like, “It’s all rickety!” [laughs]

But my mom, one of her closest friends is Carrie Mae Weems—I recognized her work in the context of the house and I saw how she was dealing with the female body. Her and Lorna Simpson would both use text in their work. It’s hard to decipher… I really only started think about this when [the] photographer Larry Sultan, one of my professors in grad school, was making art and photography. Him and Mike Mandel would get billboard companies to just give them a billboard space to do whatever they wanted. I started to realize how you could use advertising space in different ways. He shot some ads, actually, when I was in school. I recognized that you can be critical and participate at the same time.

MCDERMOTT: So how did you move from photography to working with all of these various mediums?

THOMAS: When I went to grad school at California College of the Arts, there was only one other photo major my year, so we ended up having to have an interdisciplinary practice because when I had critiques with painters and drawers, they’d be like, “I like the colors in this picture. I like the fact that you printed it big.” There wasn’t any critical dialogue. So I was thinking about the logos and things like that in popular culture. I scanned some logos from some clothes I had and started thinking about them as hieroglyphs. I made clipart in Microsoft Word to make some stuff and that became something to have a conversation about; they could talk to me about the meaning of symbols next to each other. That led me to realize that I didn’t have to use one medium to talk about topics I wanted to talk about. I almost had to learn another language.

MCDERMOTT: Do you find gratification in working on commercial projects?

THOMAS: Yeah, it’s fun. You don’t have to care. As long as you don’t mess up, it’s like, “What? You get $50,000 and you just have to make things look pretty?” [laughs] When we make this work, we have to be so much more thoughtful; it has to stand the test of time, whereas a good ad just needs to mean something for three months. When you’re supposed to make something that’s important 10 or 20, or hopefully 100 years from now, that’s a much taller order.

MCDERMOTT: Can we talk a bit about Question Bridge? It’s the first work of yours that I saw, actually, when your mom took us to the Brooklyn Museum.

THOMAS: [laughs] People are always like, “She’s always talking about her son!” But for me, none of the work is about race. It’s about people and what happens when people are put into groups—how they relate to the group that they’ve been put into and how they see themselves. Can they find agency or not within these groups? So Question Bridge, by asking all these self-identified African American males to ask and answer each other’s questions, we were showing there’s as much diversity within any demographic as there is outside of it. Because, if you show the same question to five people, even if they have the same gender and skin complexion, you can guarantee they’re not going to answer the same way if it’s an open-ended or targeted question. That was the reason for doing the project, to really highlight that.

MCDERMOTT: That was one of the first times you worked with video. How did you then start to incorporate sculpture?

THOMAS: I realized that to do some of the things that I want to do, it [had to become] a collaborative process, on a certain level, that is led or directed by me. I’m not an expert carpenter. I will find materials and the person who is the best to do it, and I’ll work with them to help realize whatever I want to do. It’s not a pretty process. [Everything starts with research] and typically takes a year at least, usually a couple years to fully mature.

MCDERMOTT: When you’re involved in these years-long projects, do you find that they consume your entire life, or that you can come to the studio, do your research, and then go home at night?

THOMAS: My entire life is always consumed. The projects never stop. I think for all of us, but I think for me as an African American artist, you don’t want to be pigeon holed. I have made a lot of work about race and blackness and gender, so working in different mediums, working in different themes, is important. Race, blackness, and gender are not all I care about and you could easily get the wrong impression by just looking at a few pieces.

MCDERMOTT: A lot of your work deals with this idea of untruths. Would you say that one of your goals is to reveal truths?

THOMAS: Well, yeah, it’s about truths, trying to show there are different perspectives. It’s all about point of view and how your point of view is your avenue to interpreting and understanding the world. The truth is that I can only see a little bit of what is going on in this room.

MCDERMOTT: Another theme is this idea of double consciousness.

THOMAS: It’s the same thing, that awareness of these are things I value, but I also value other things. People might presume what I value based off of what they see, and I might be aware of that, but I’m not going to be dictated by that.

“UNBRANDED: A CENTURY OF WHITE WOMEN, 1915-2015” IS ON VIEW TODAY, APRIL 10, THROUGH MAY 23 AT JACK SHAINMAN GALLERY, NEW YORK.